PRESENT TO FUTURE

Un proyecto de Jordi Bernadó y Santiago Garcés.

Aprovechando una alineación favorable entre Júpiter y Saturno, el programa Voyager lanzó en 1977 dos naves espaciales en una misión interestelar. A bordo de cada una viaja un disco de gramófono con una compilación de sonidos terrestres: rugidos y cantos animales, voces humanas, risas, ruido de pisadas, mensajes en código morse. El objetivo: lanzar un mensaje a la deriva. ¿De amor? ¿De esperanza? Aunque las probabilidades de encontrar vida extraterrestre son mínimas, Voyager es un ejercicio de fe. Fe en el encuentro, en las posibilidades de entendernos más allá de las distancias.

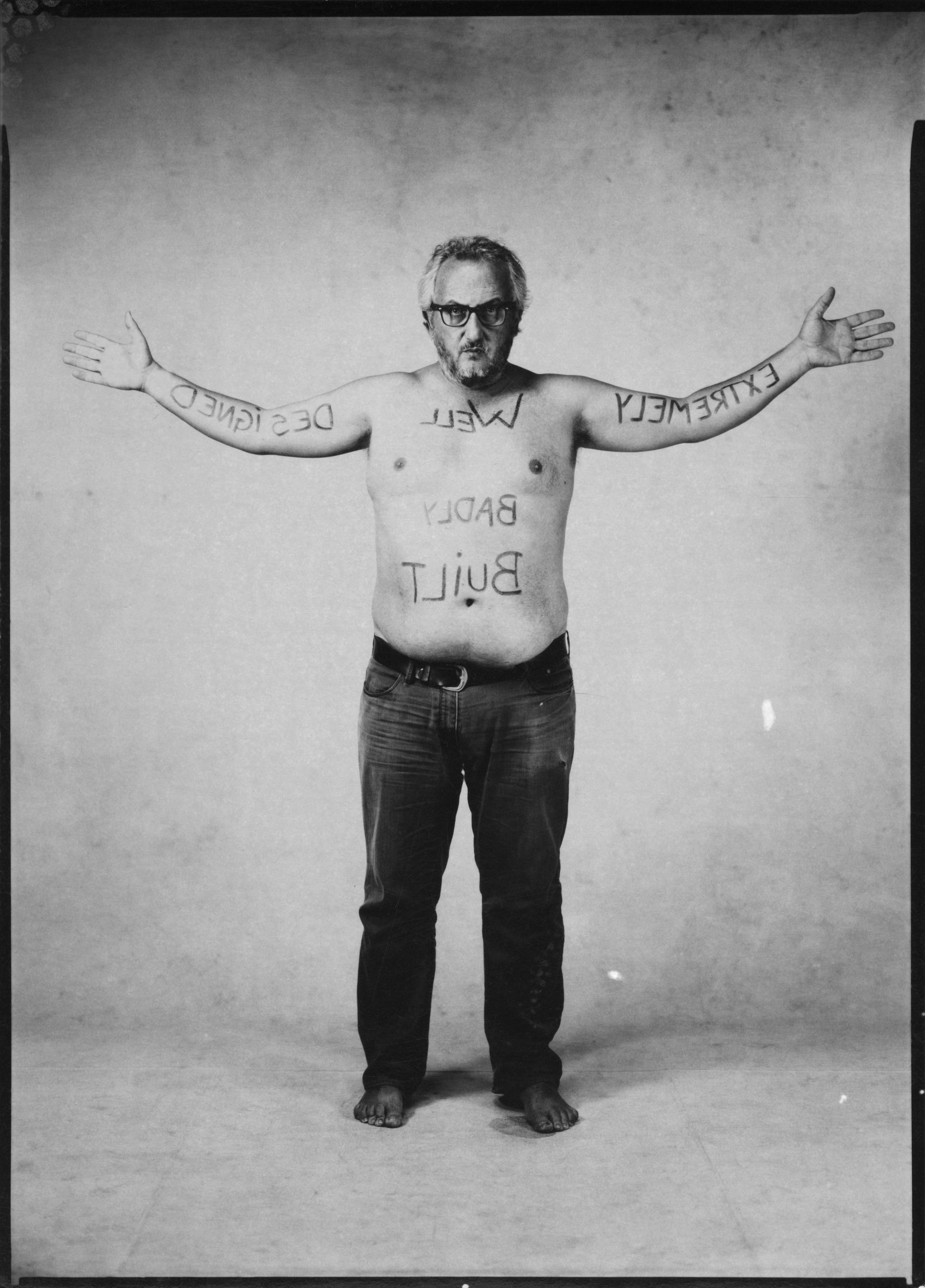

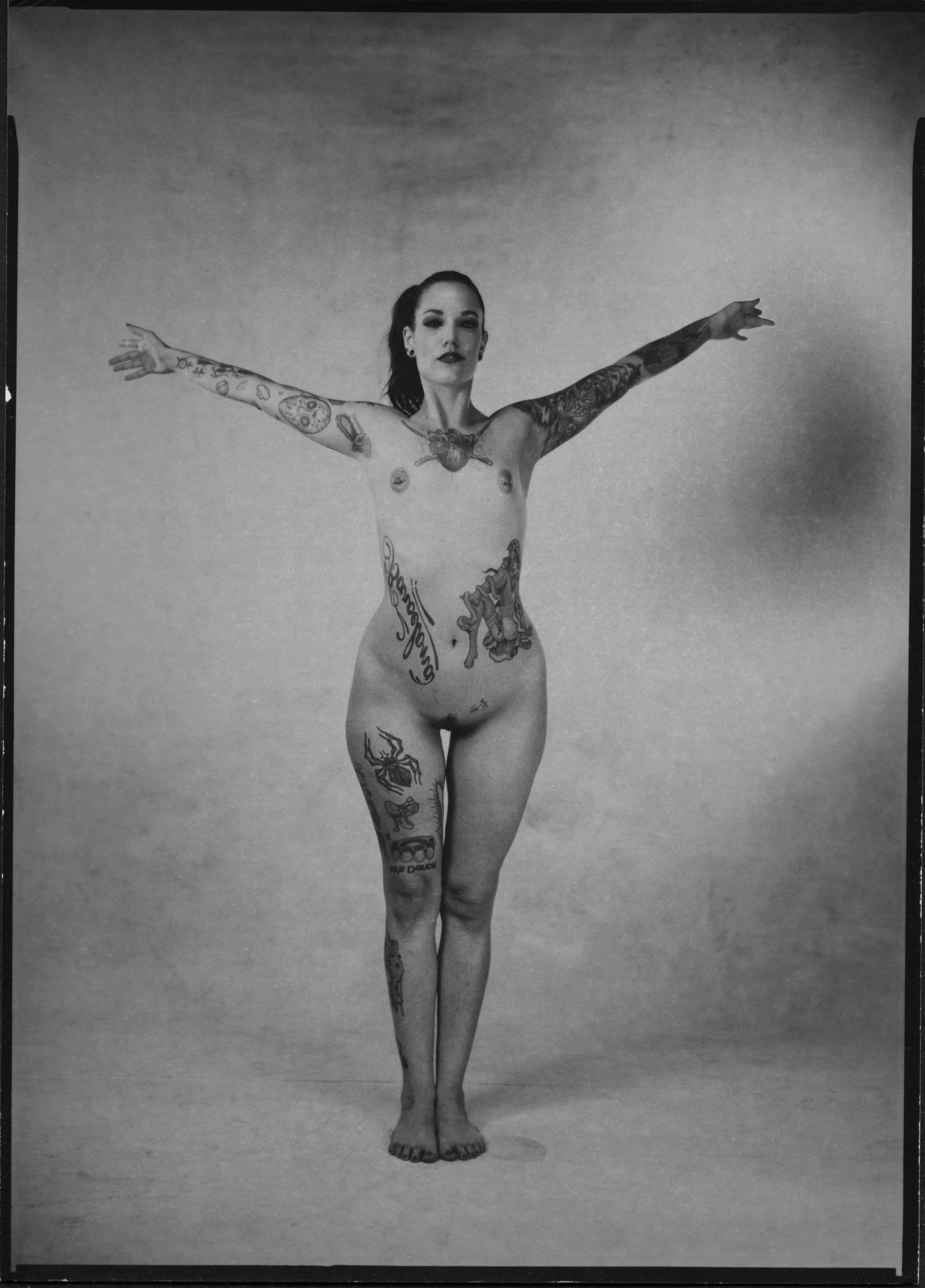

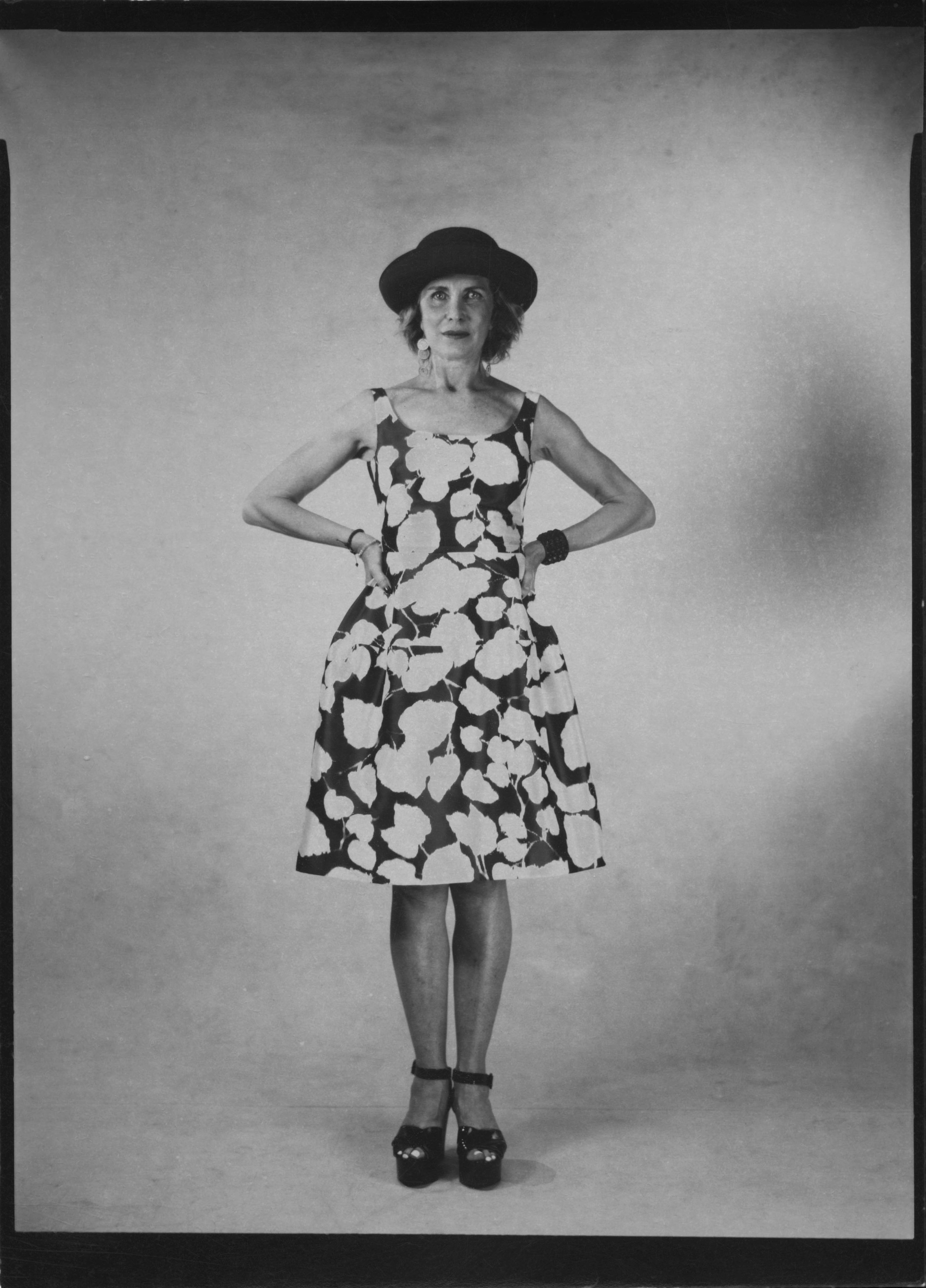

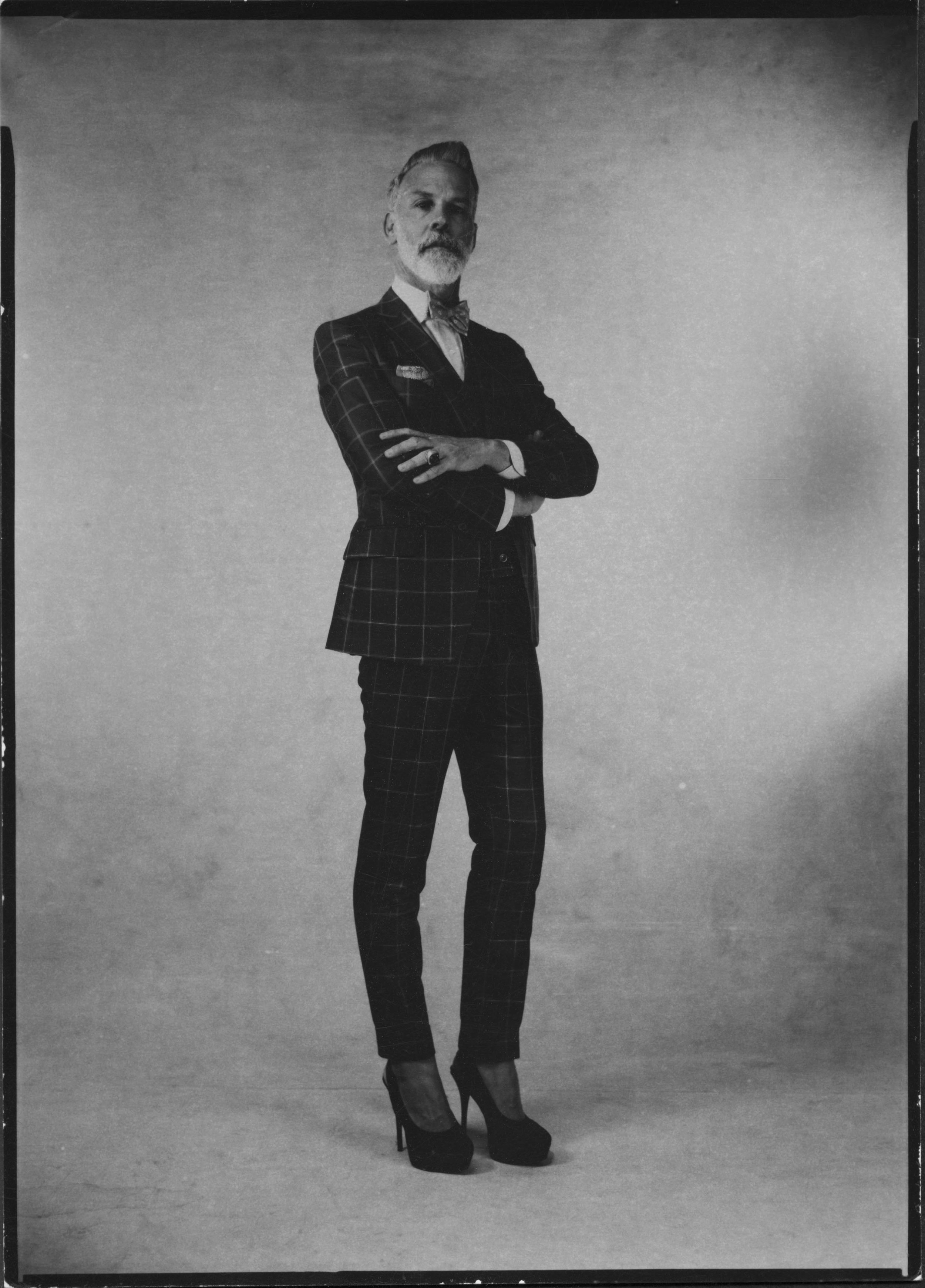

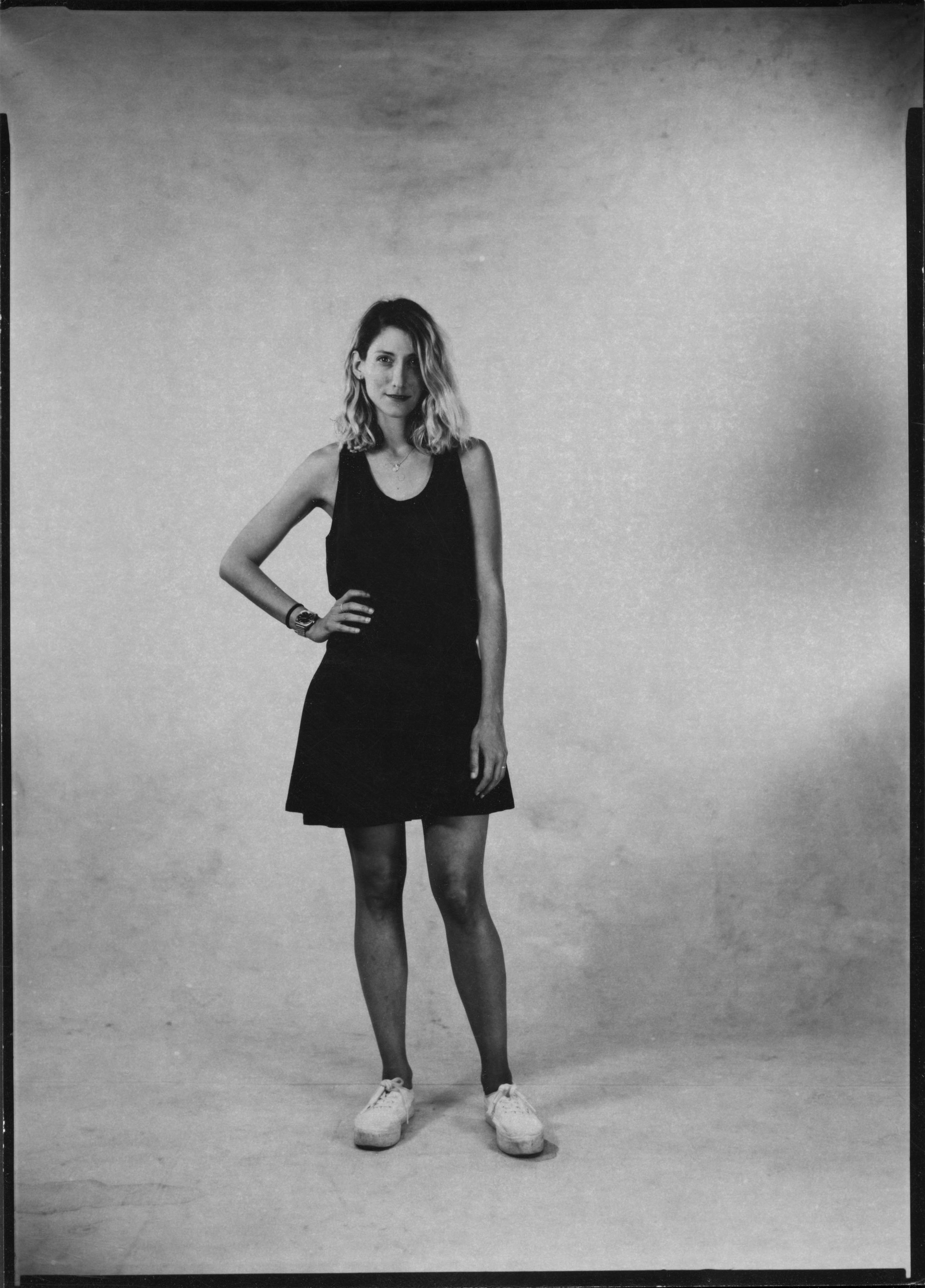

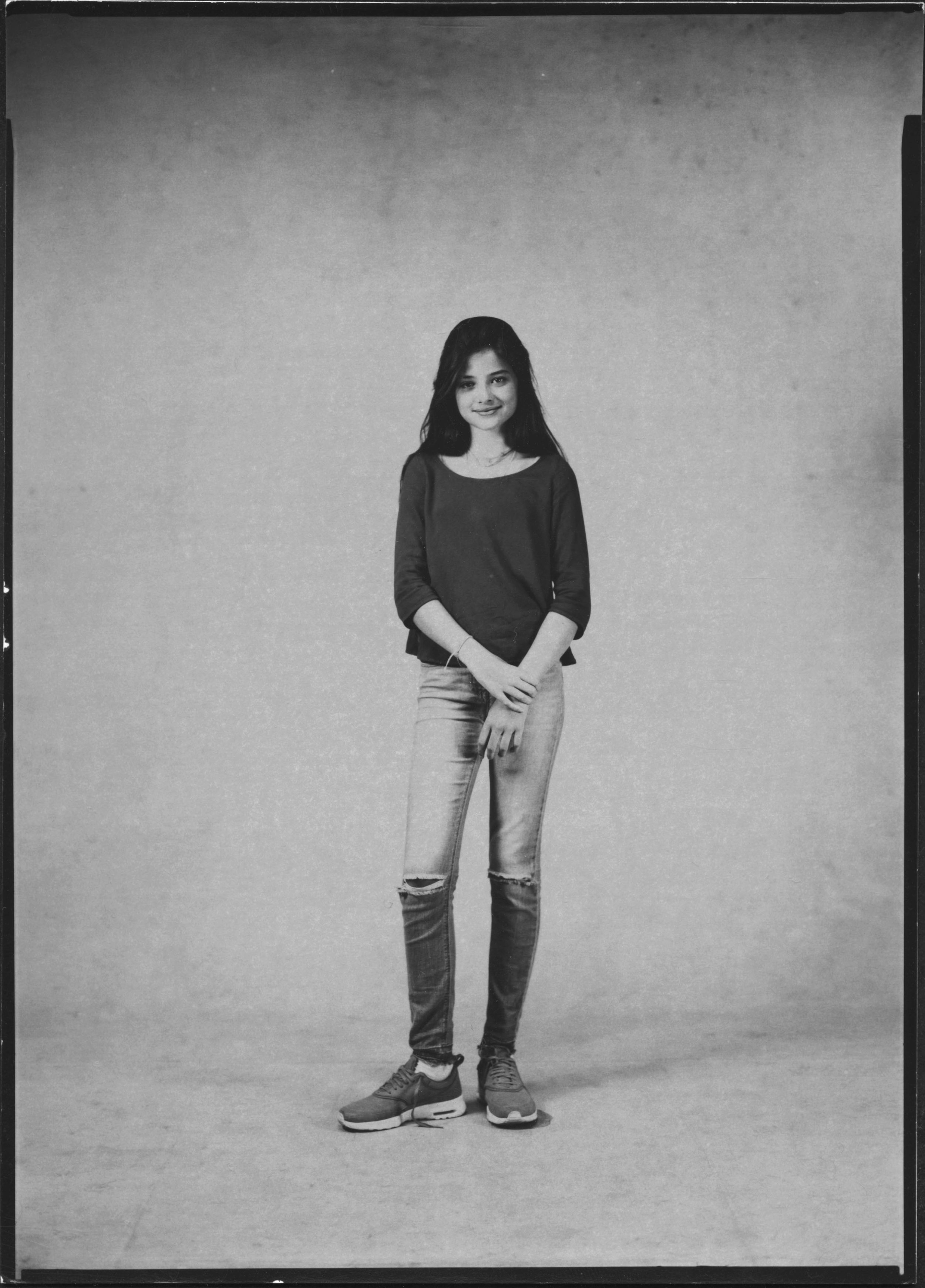

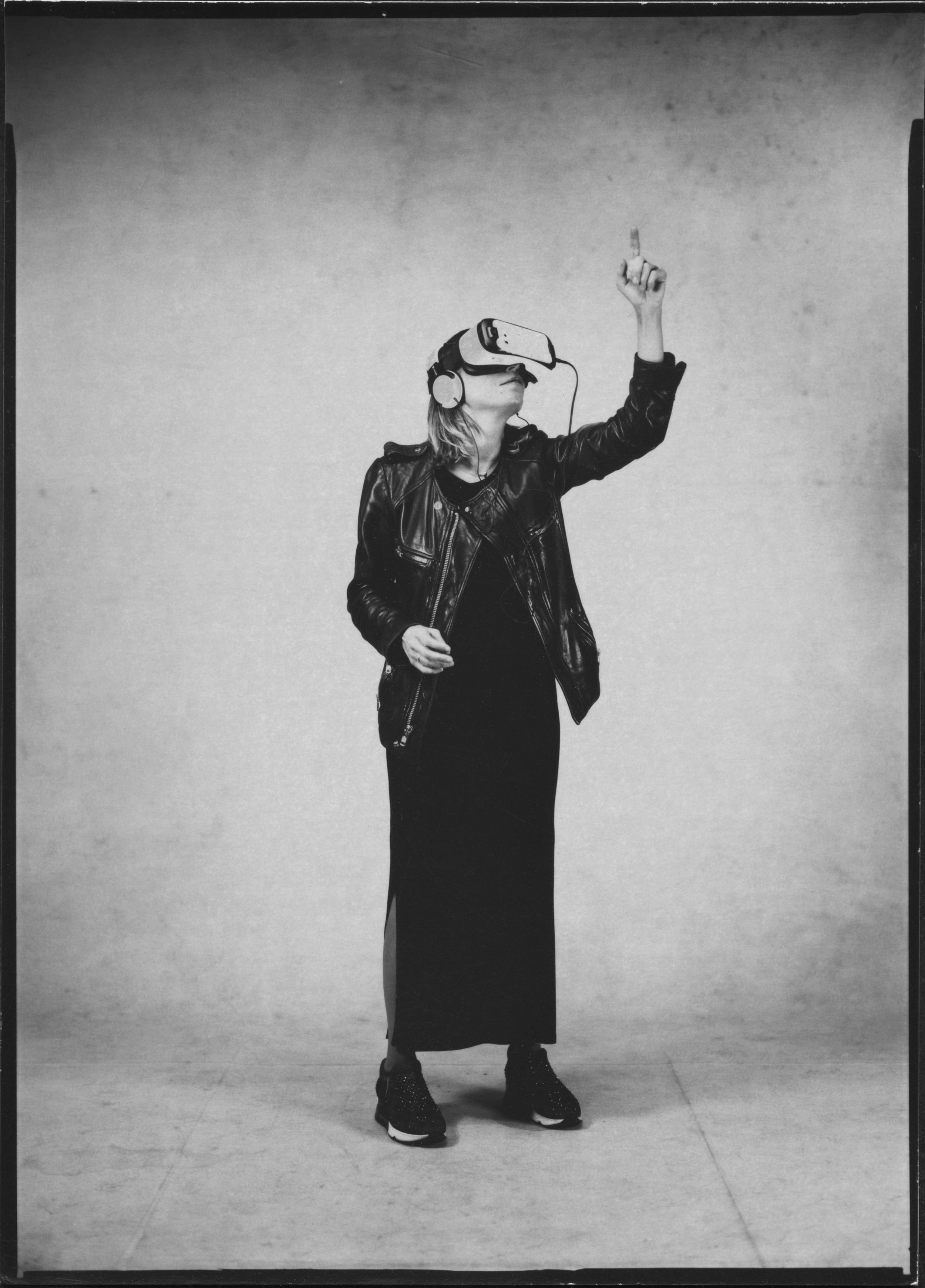

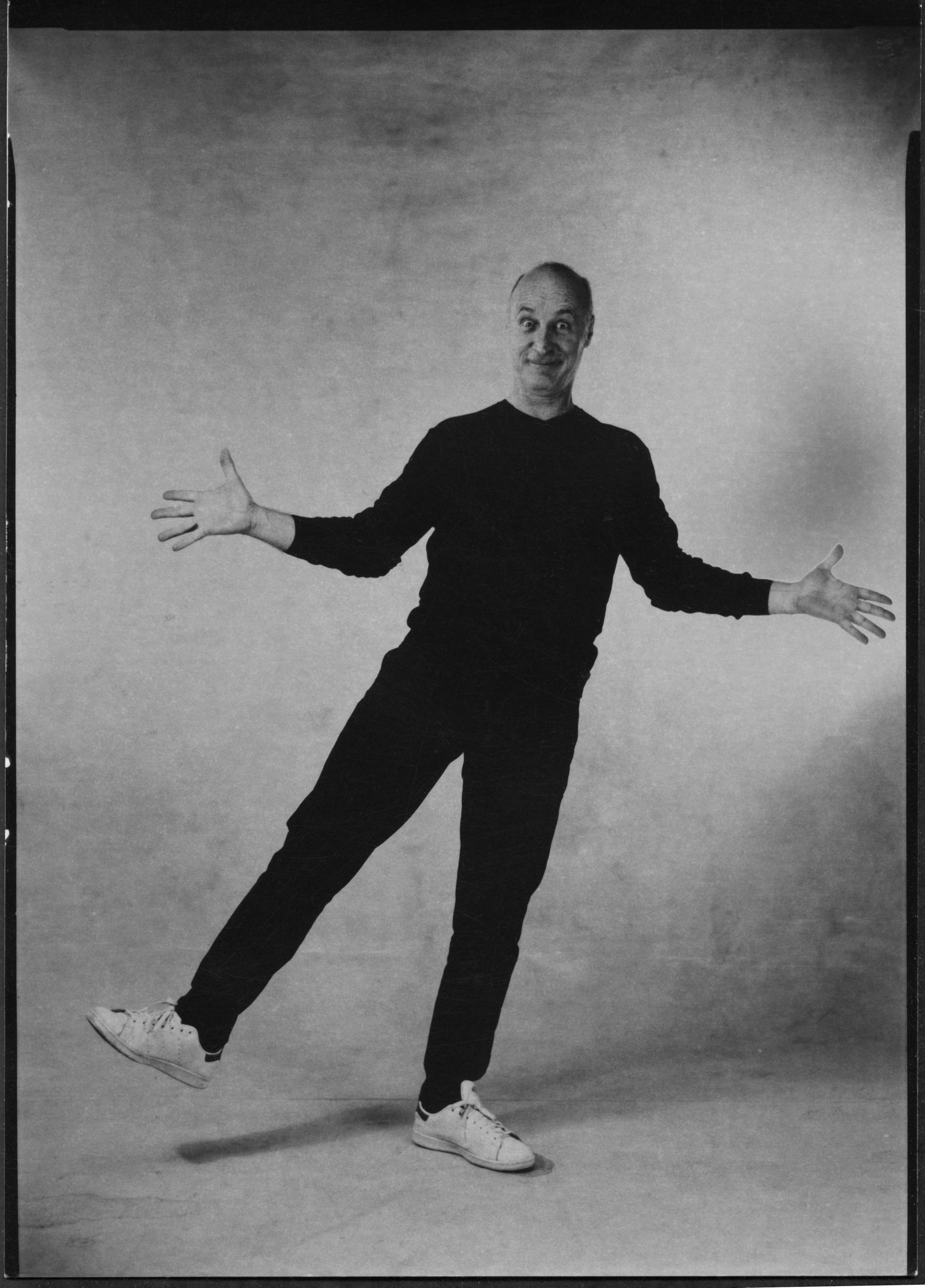

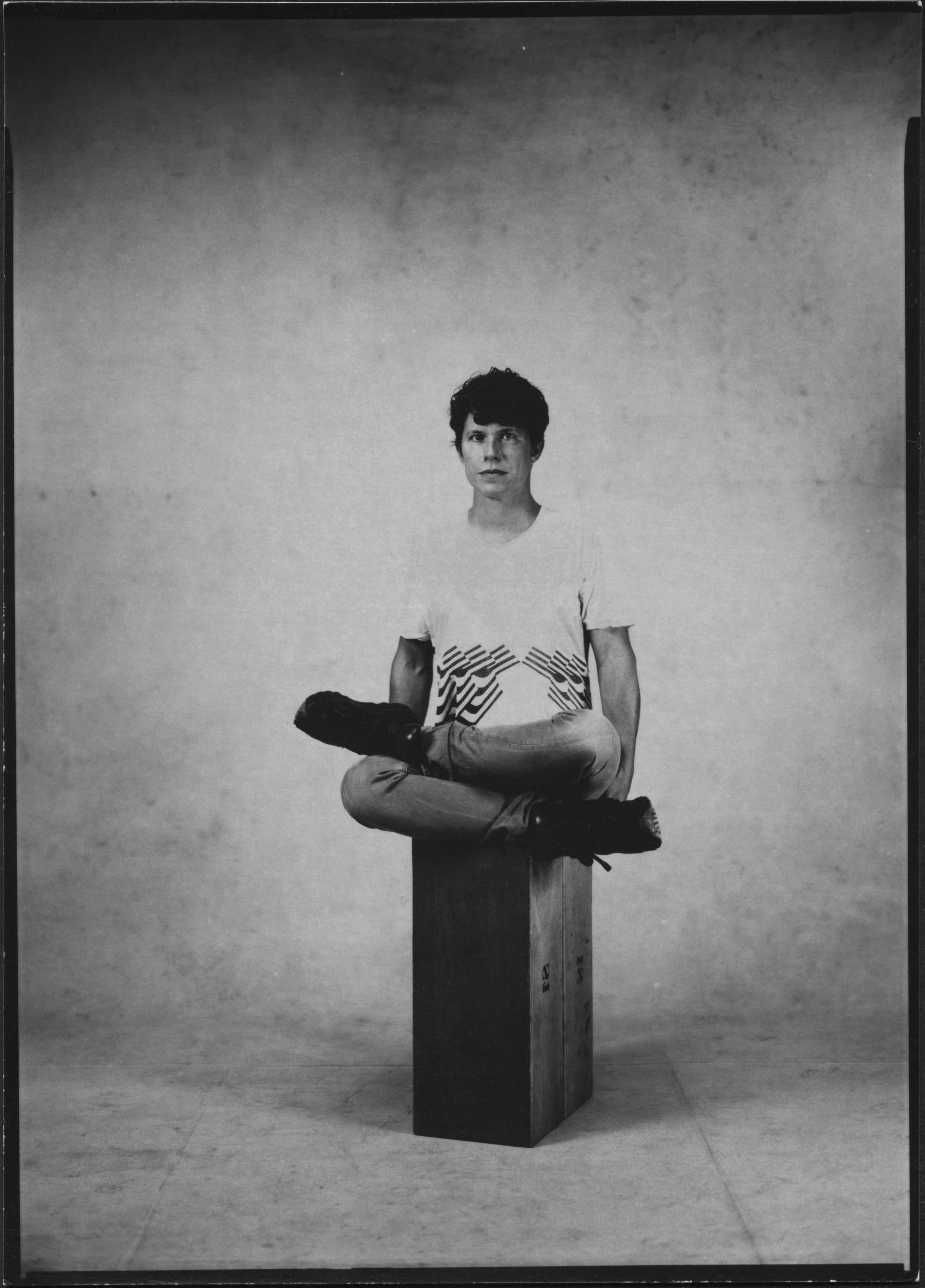

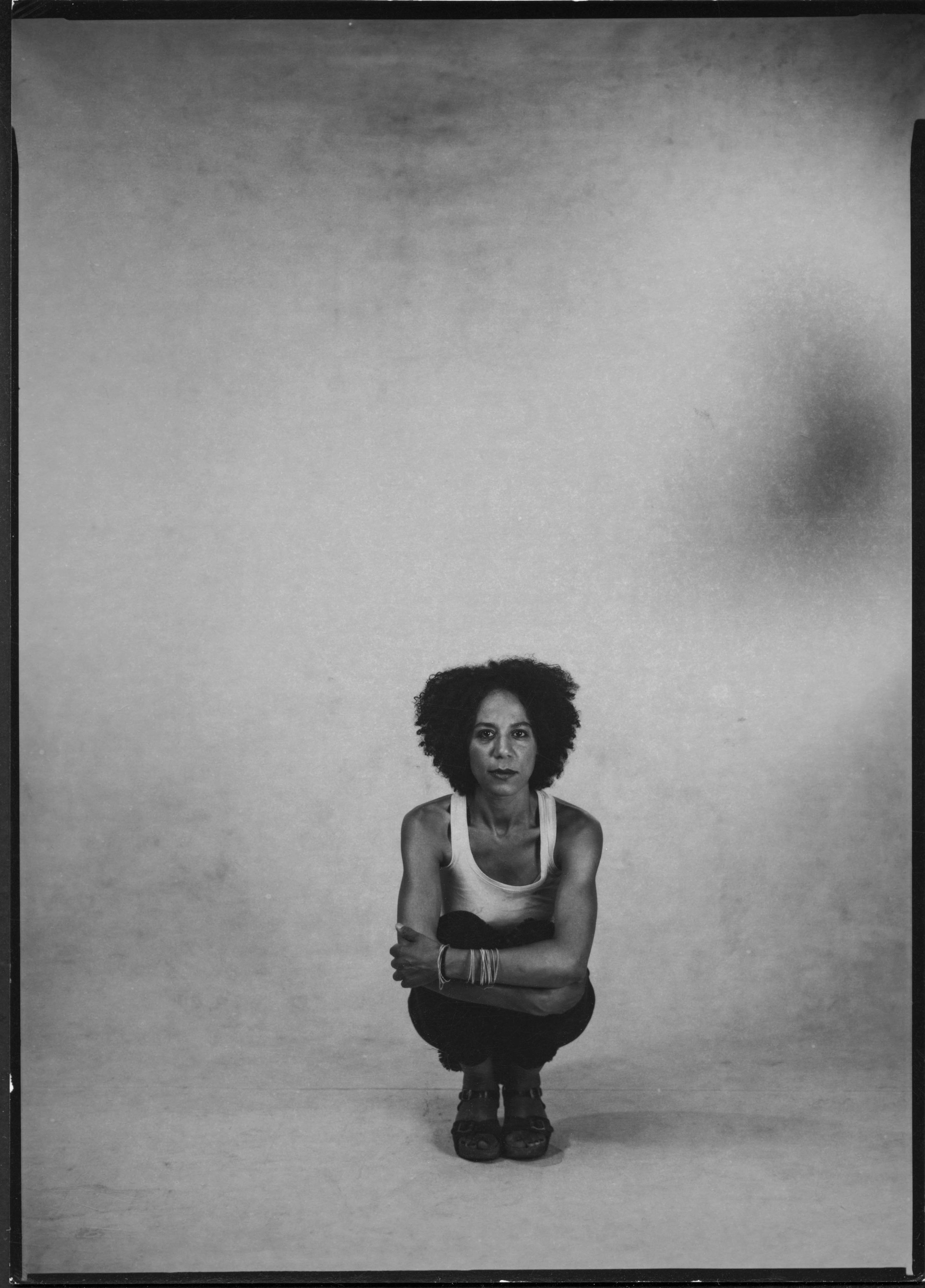

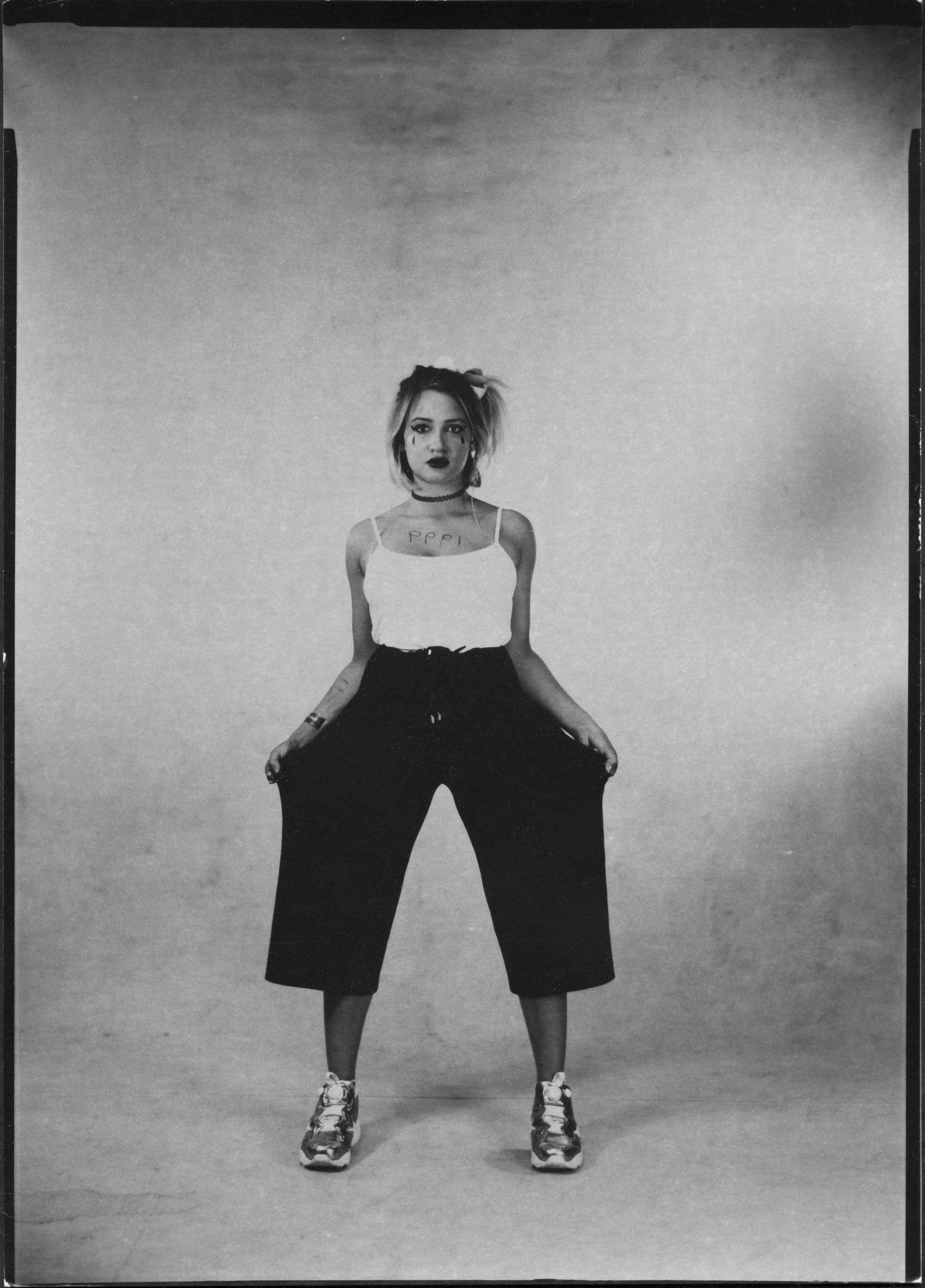

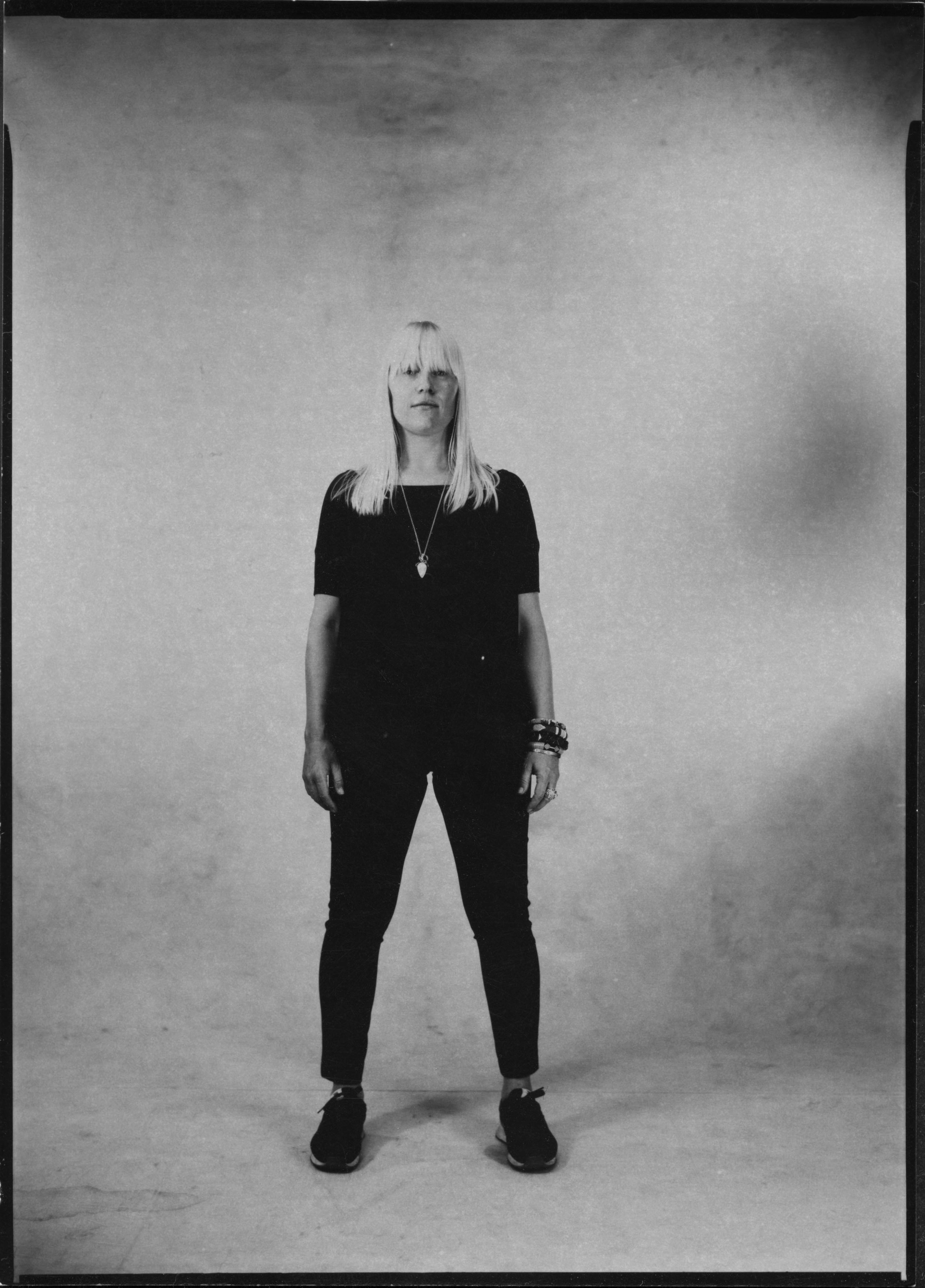

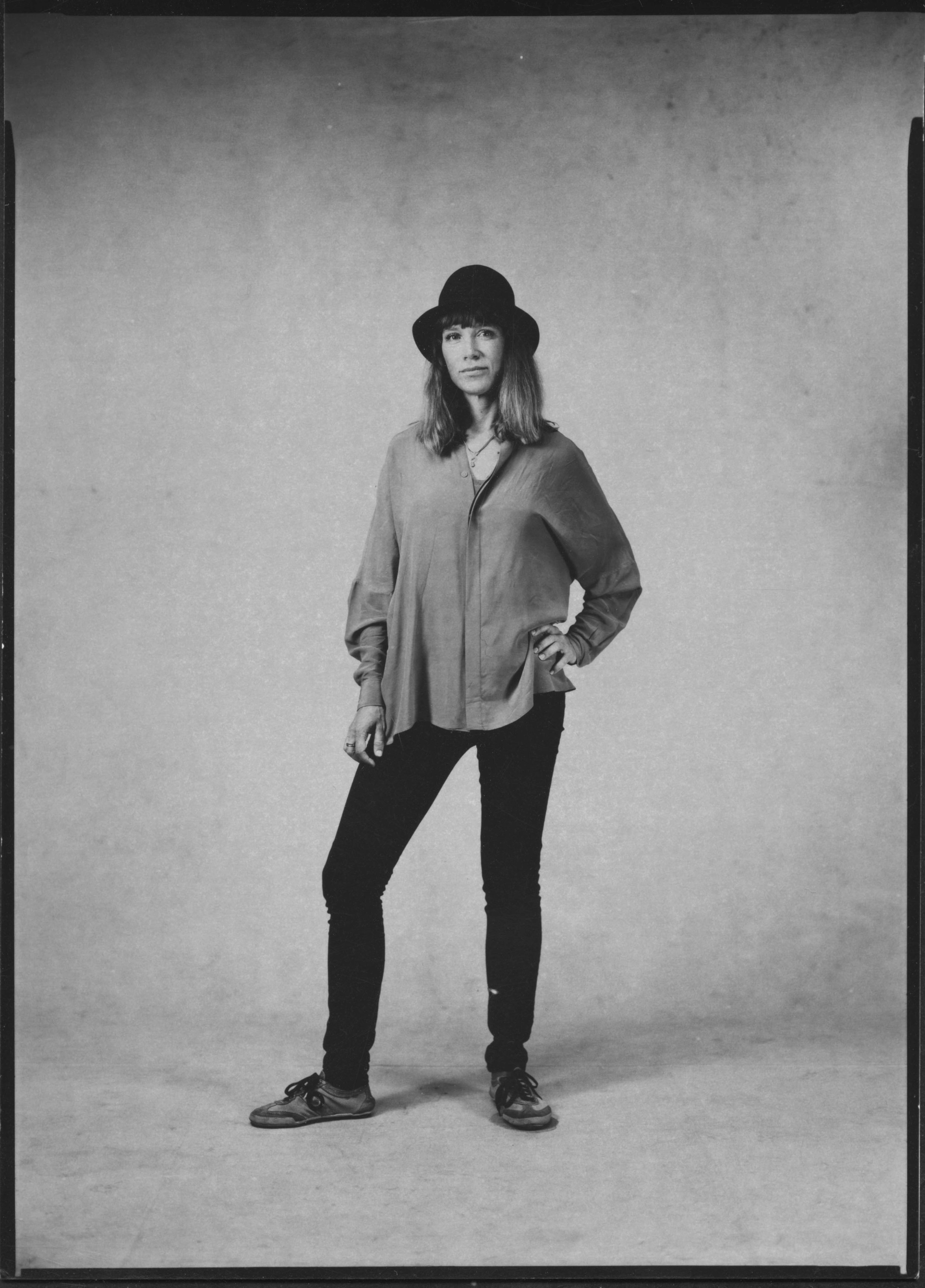

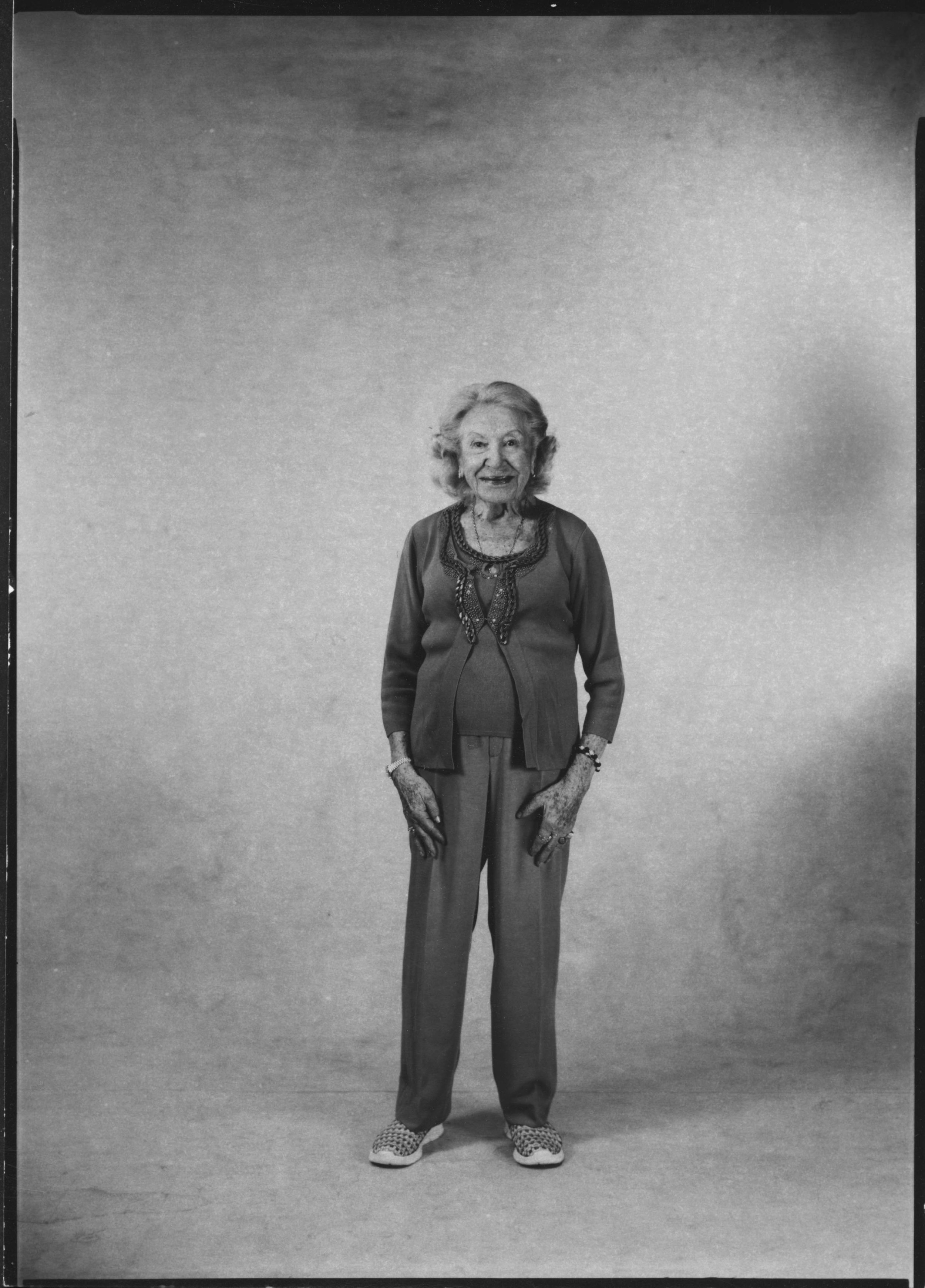

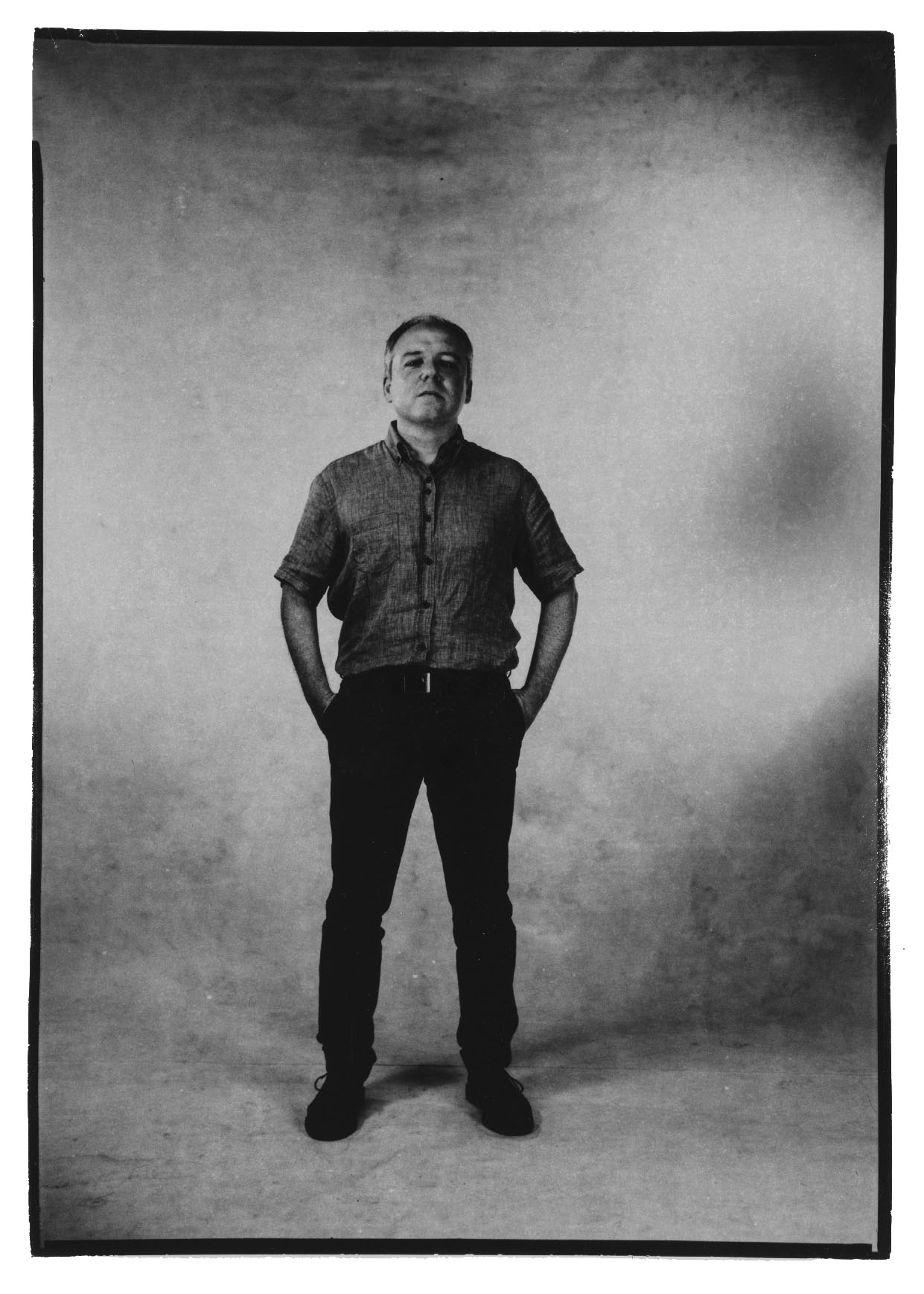

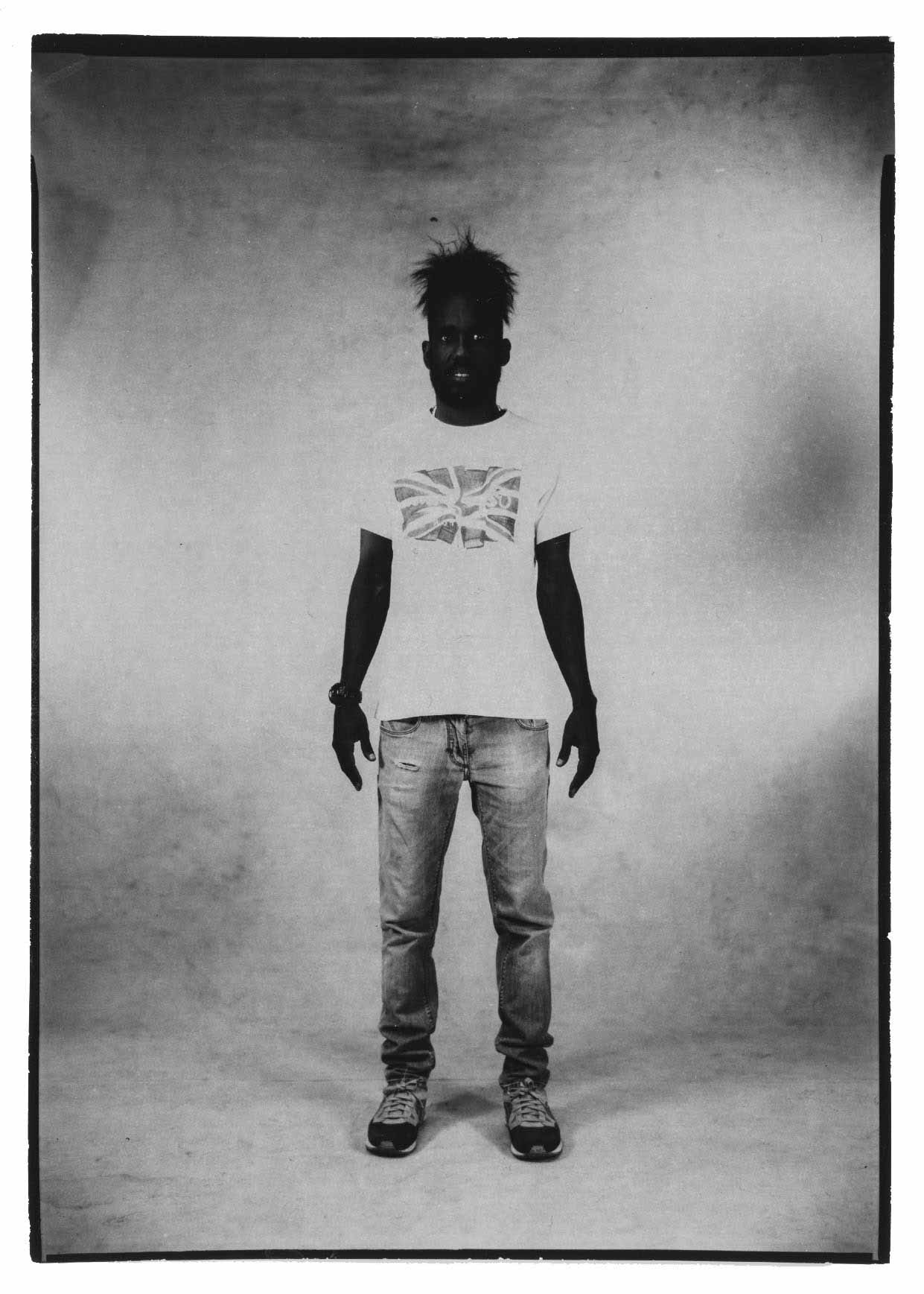

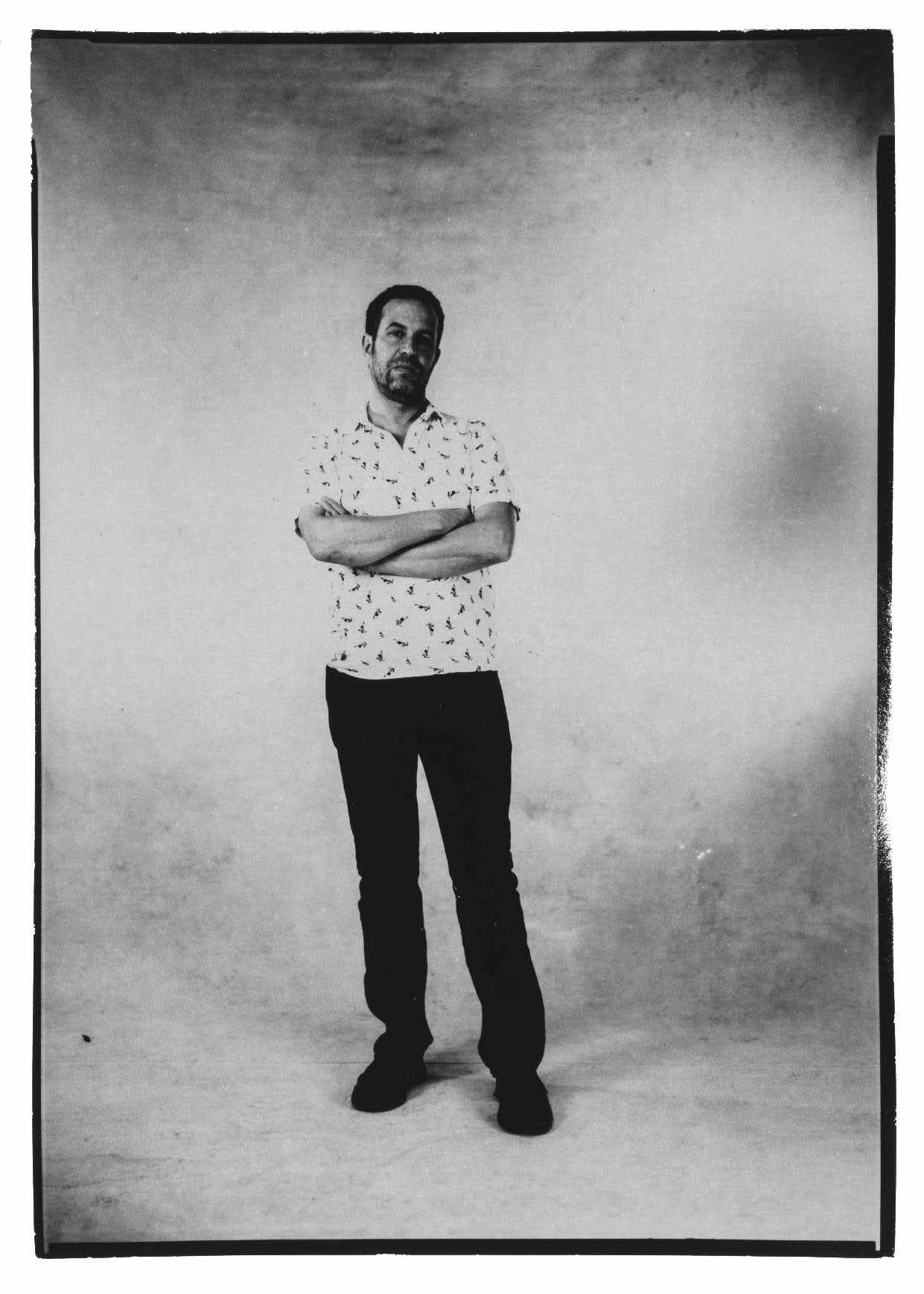

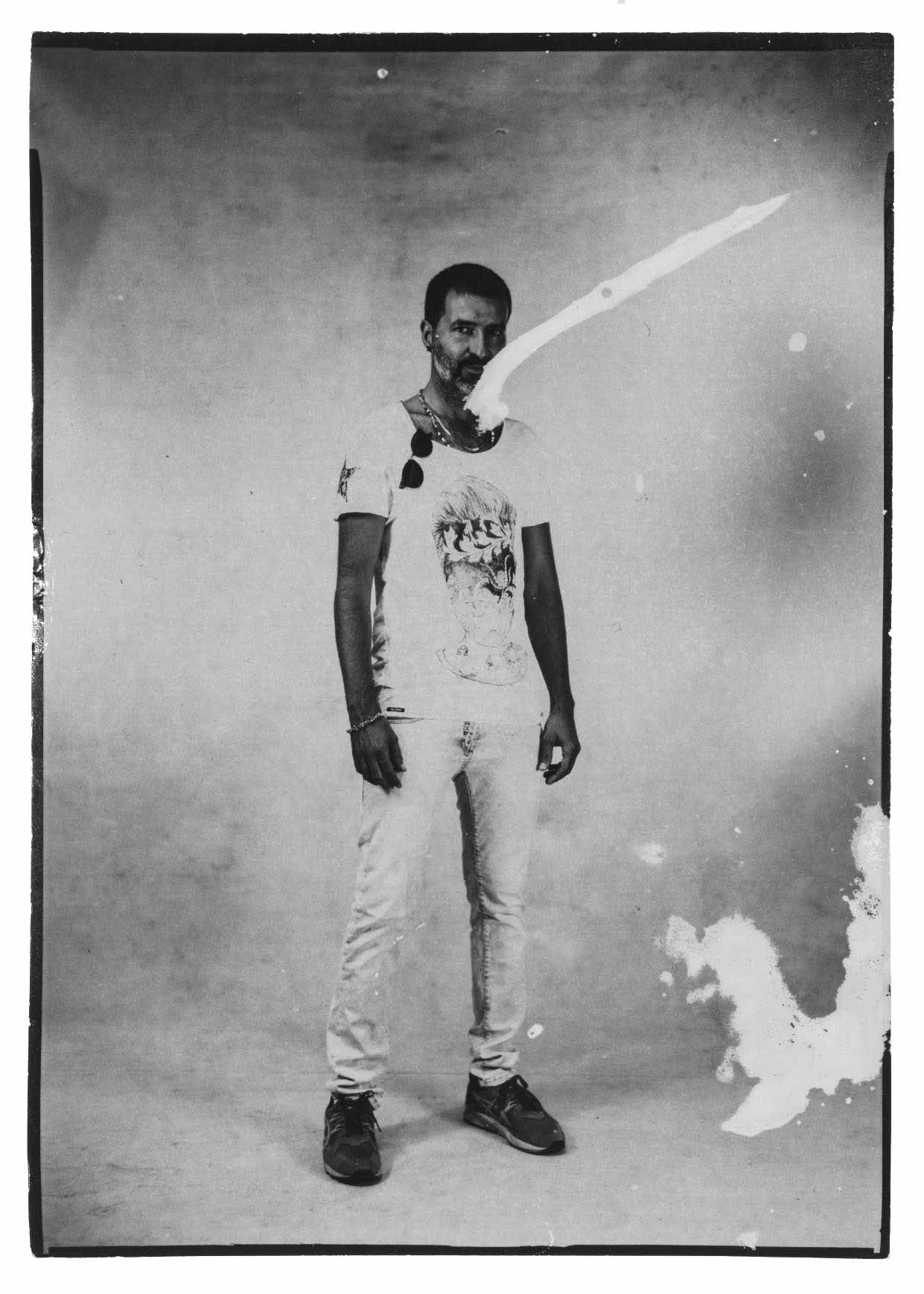

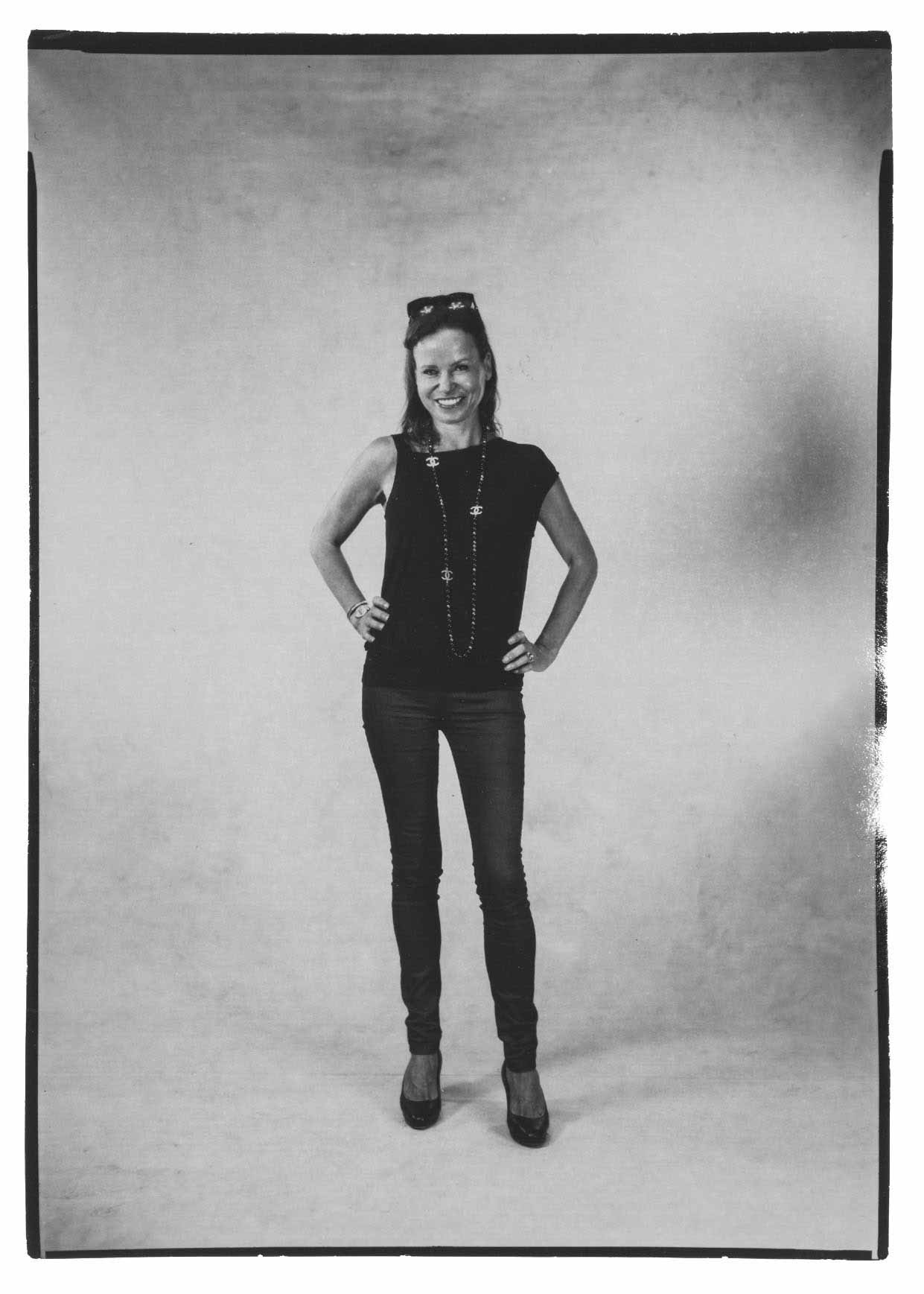

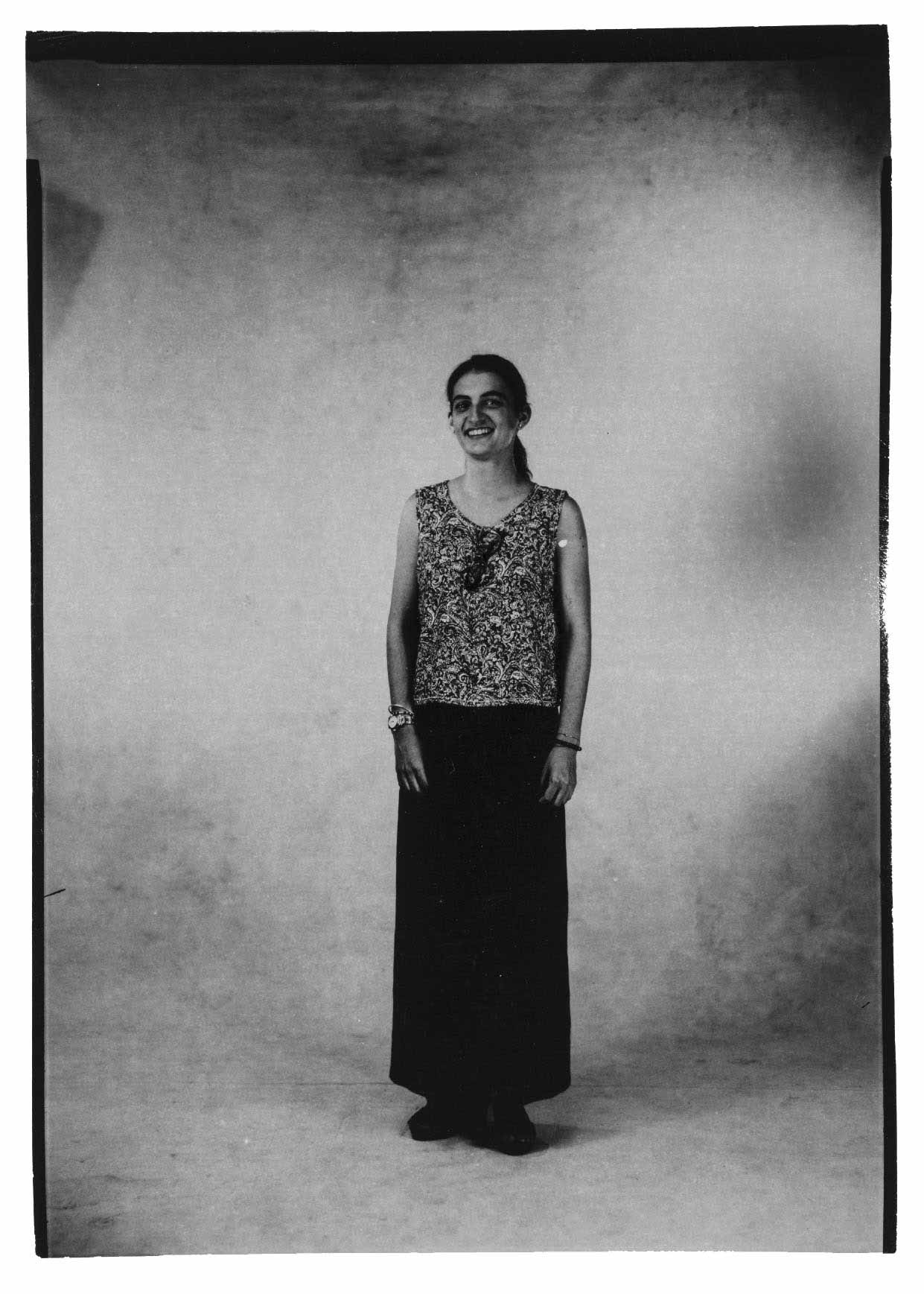

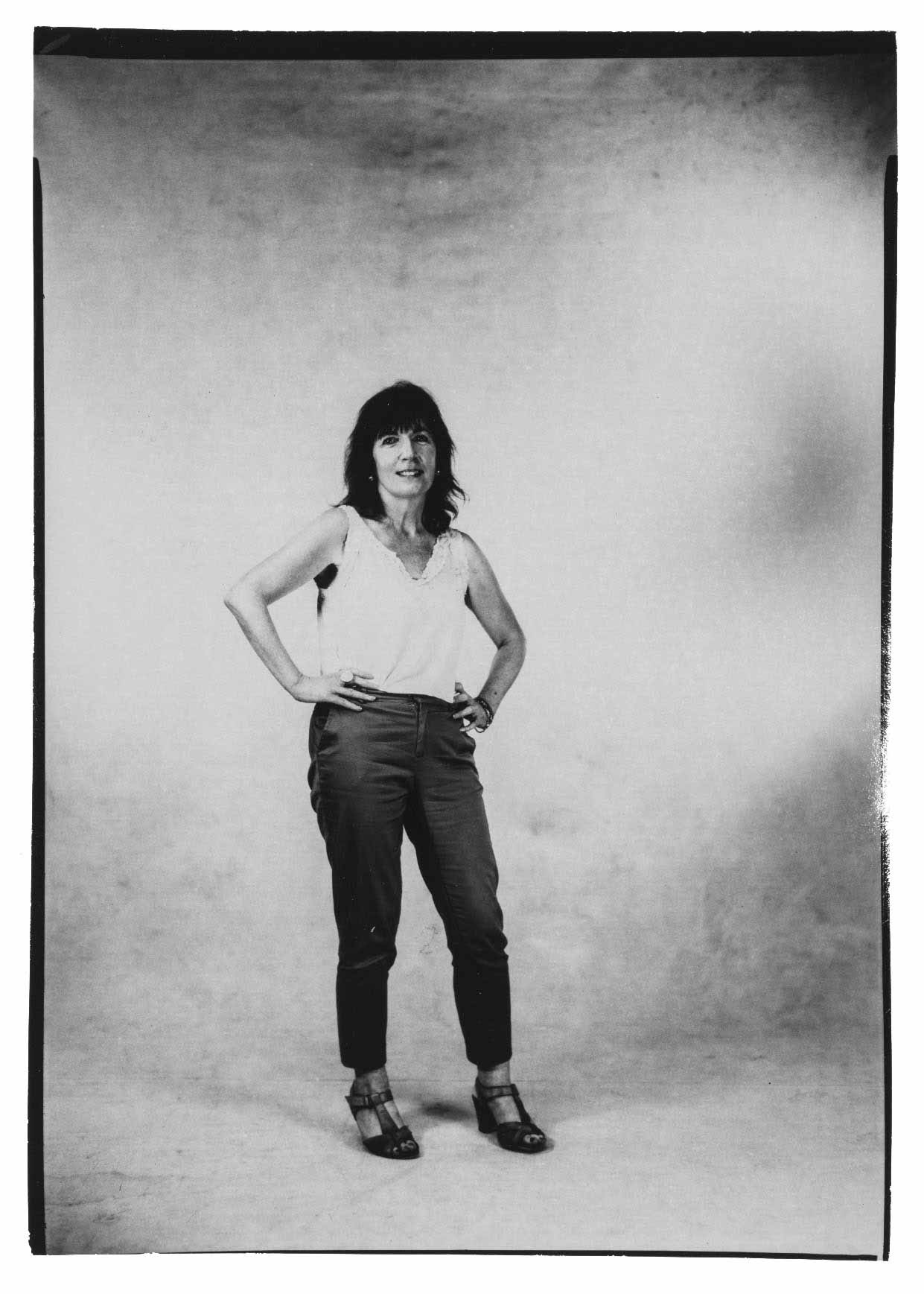

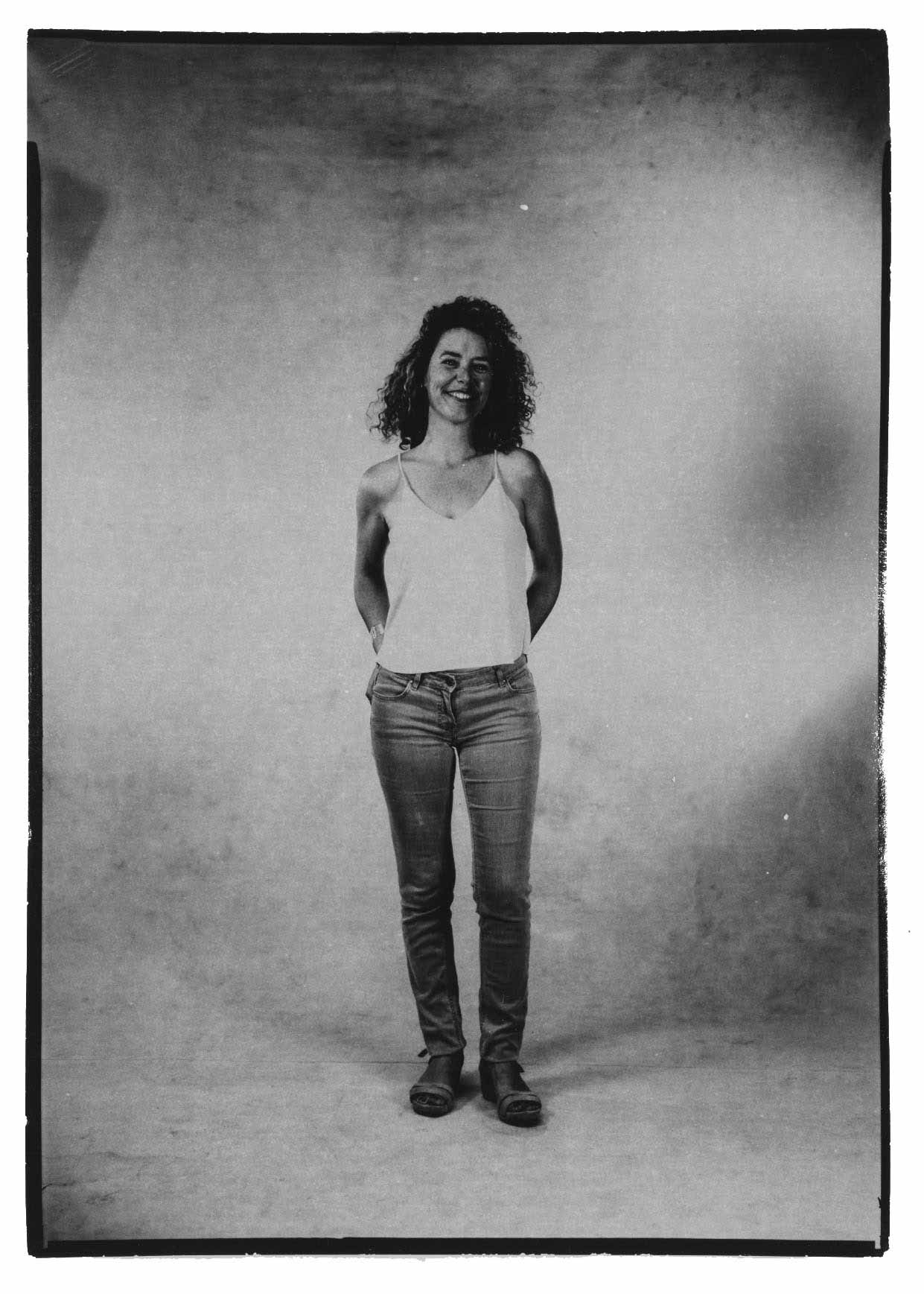

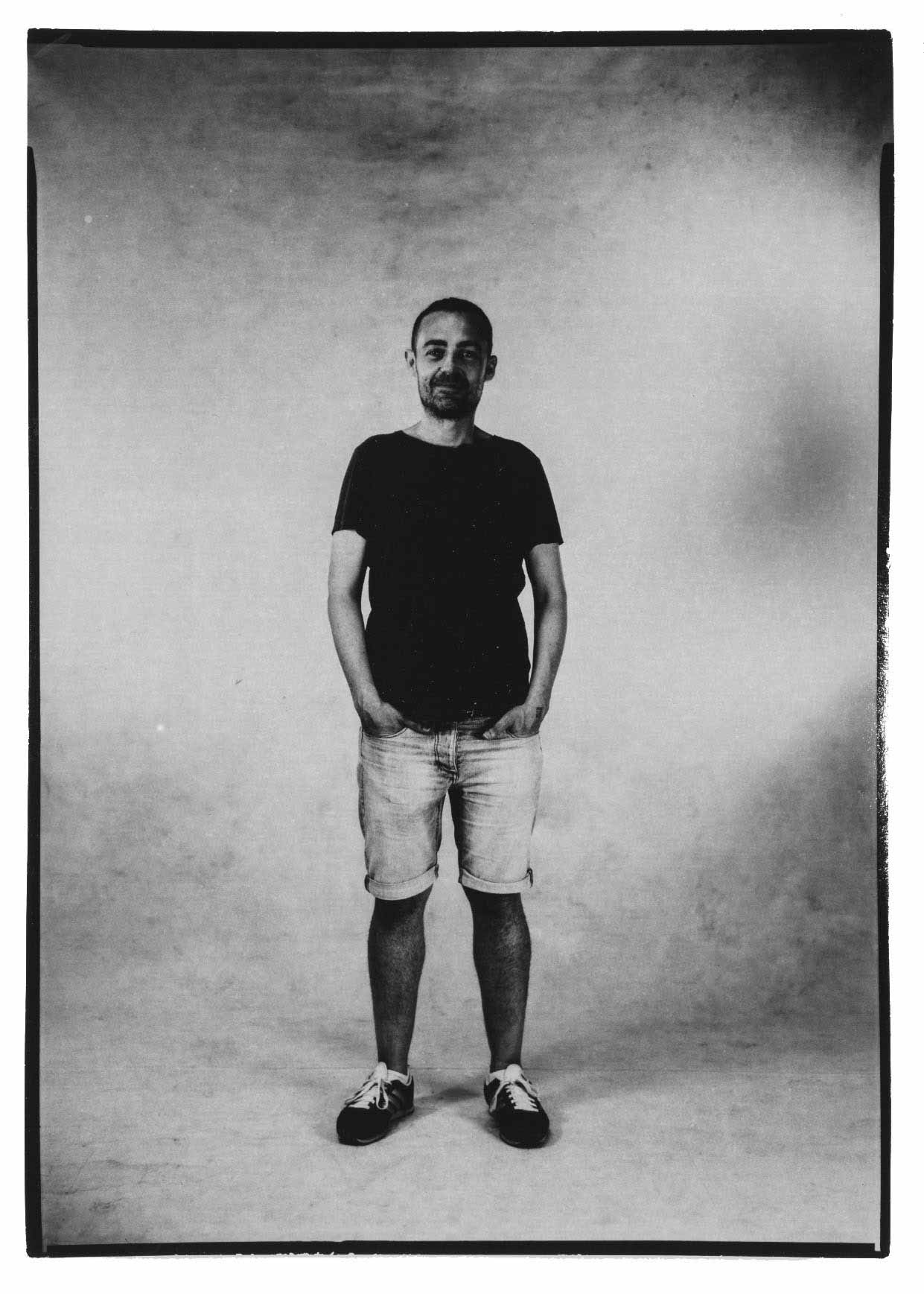

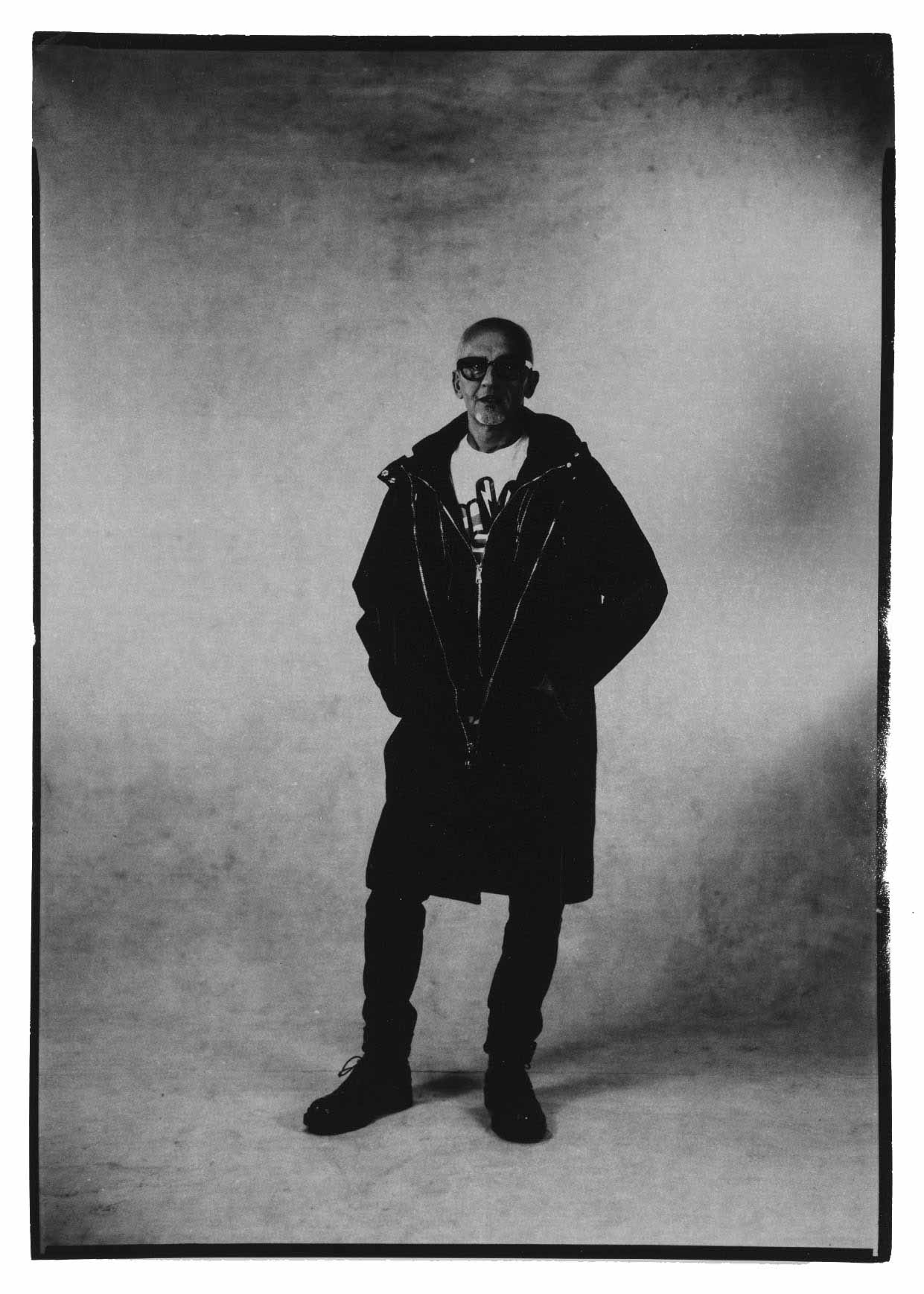

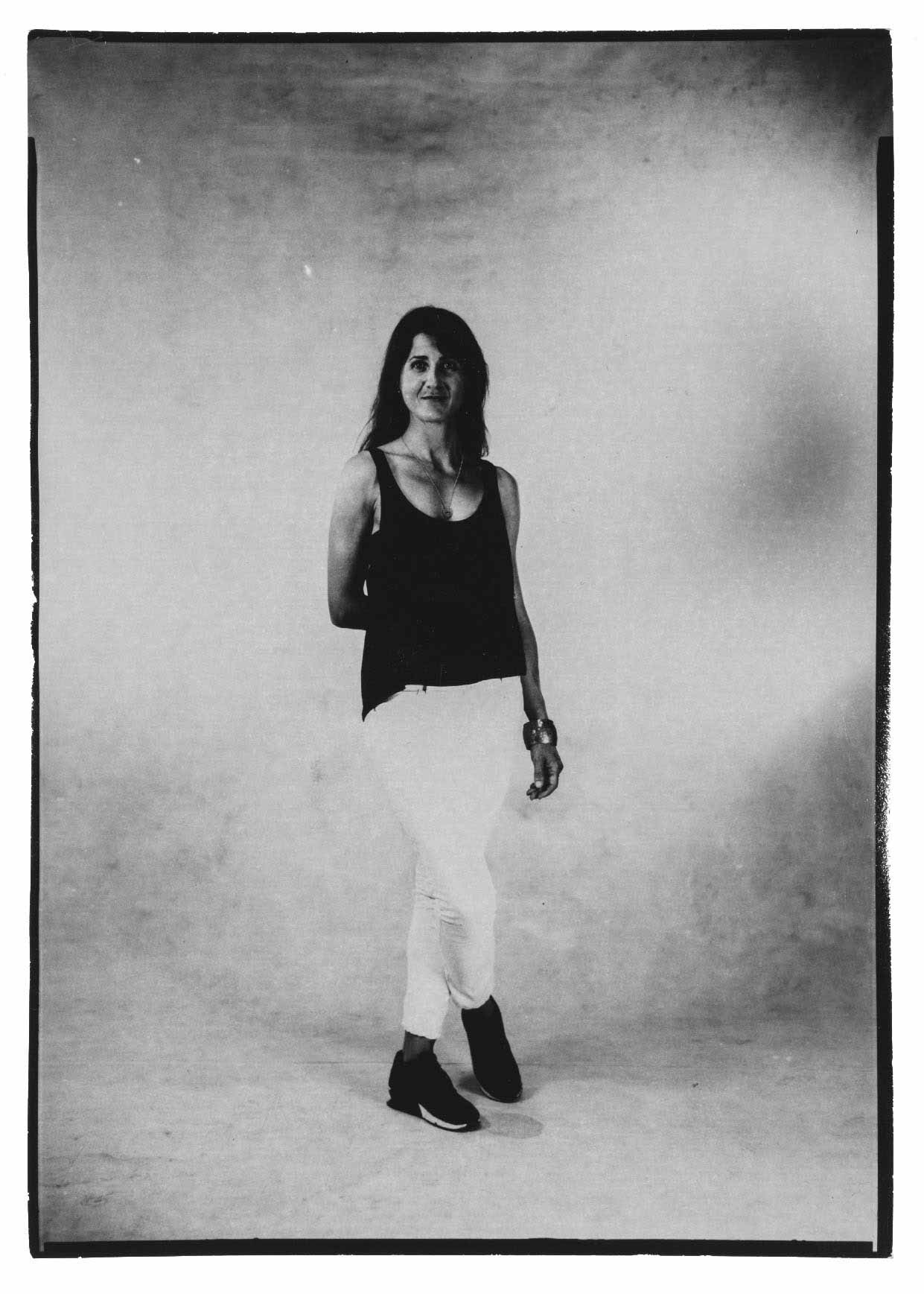

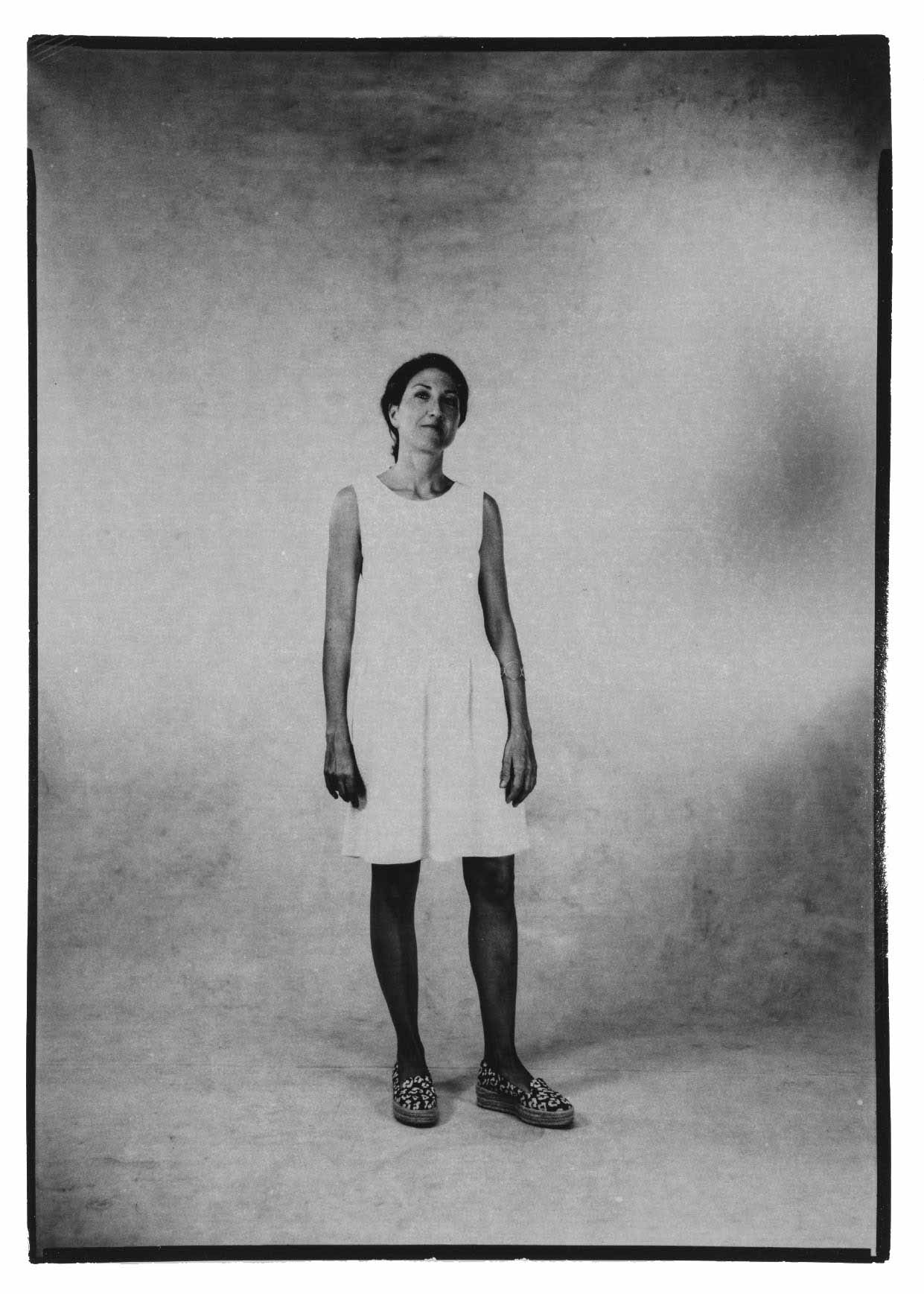

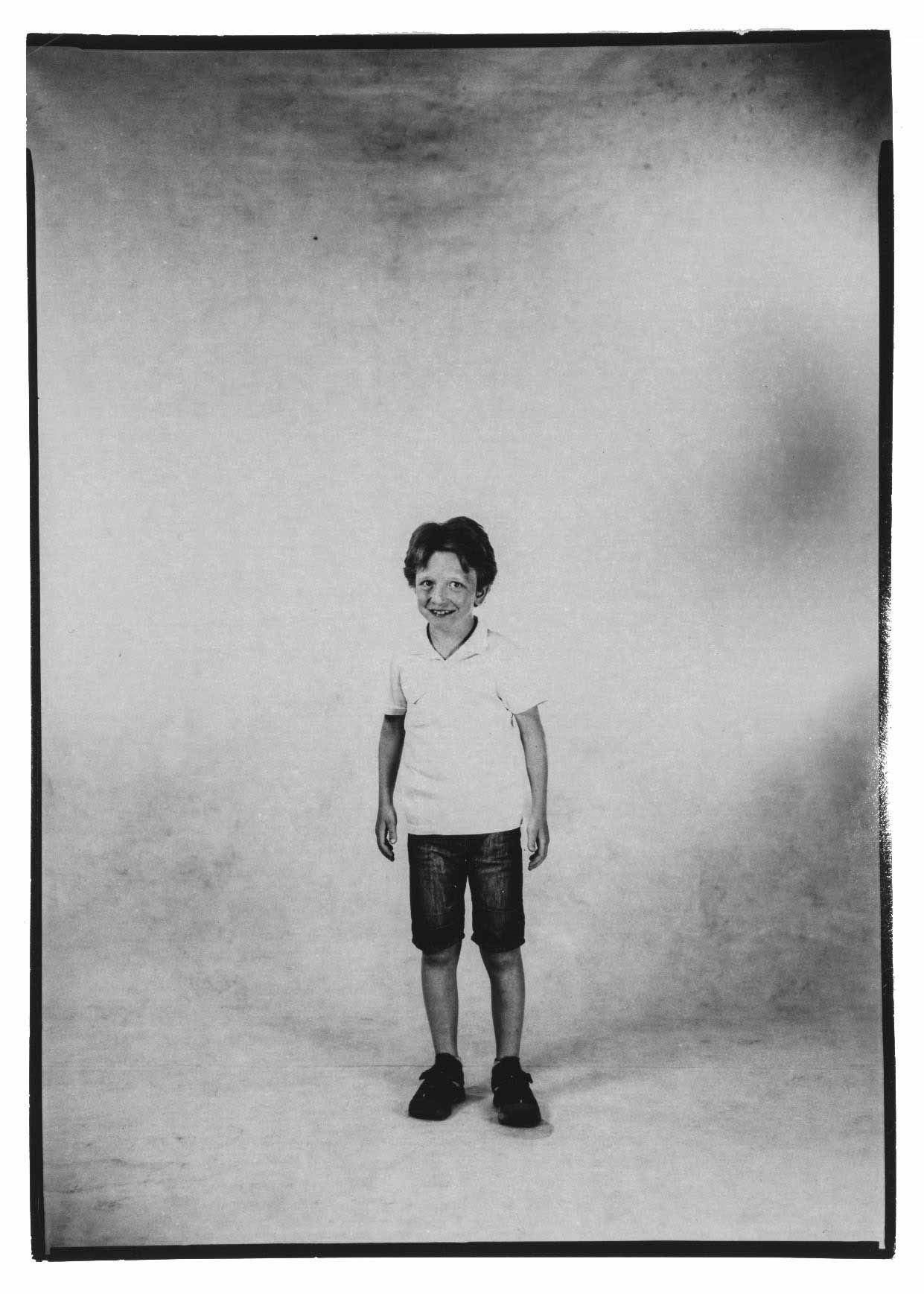

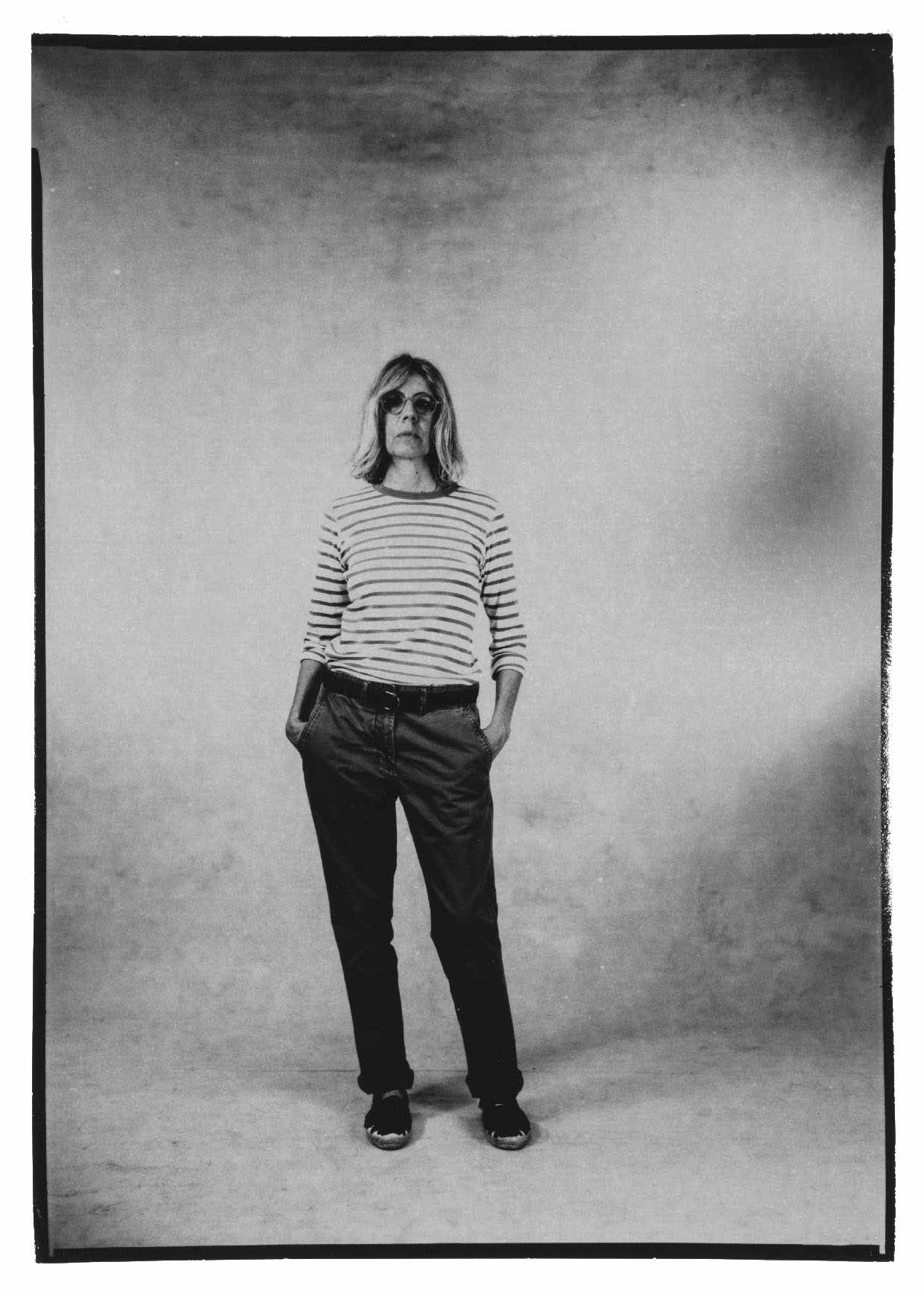

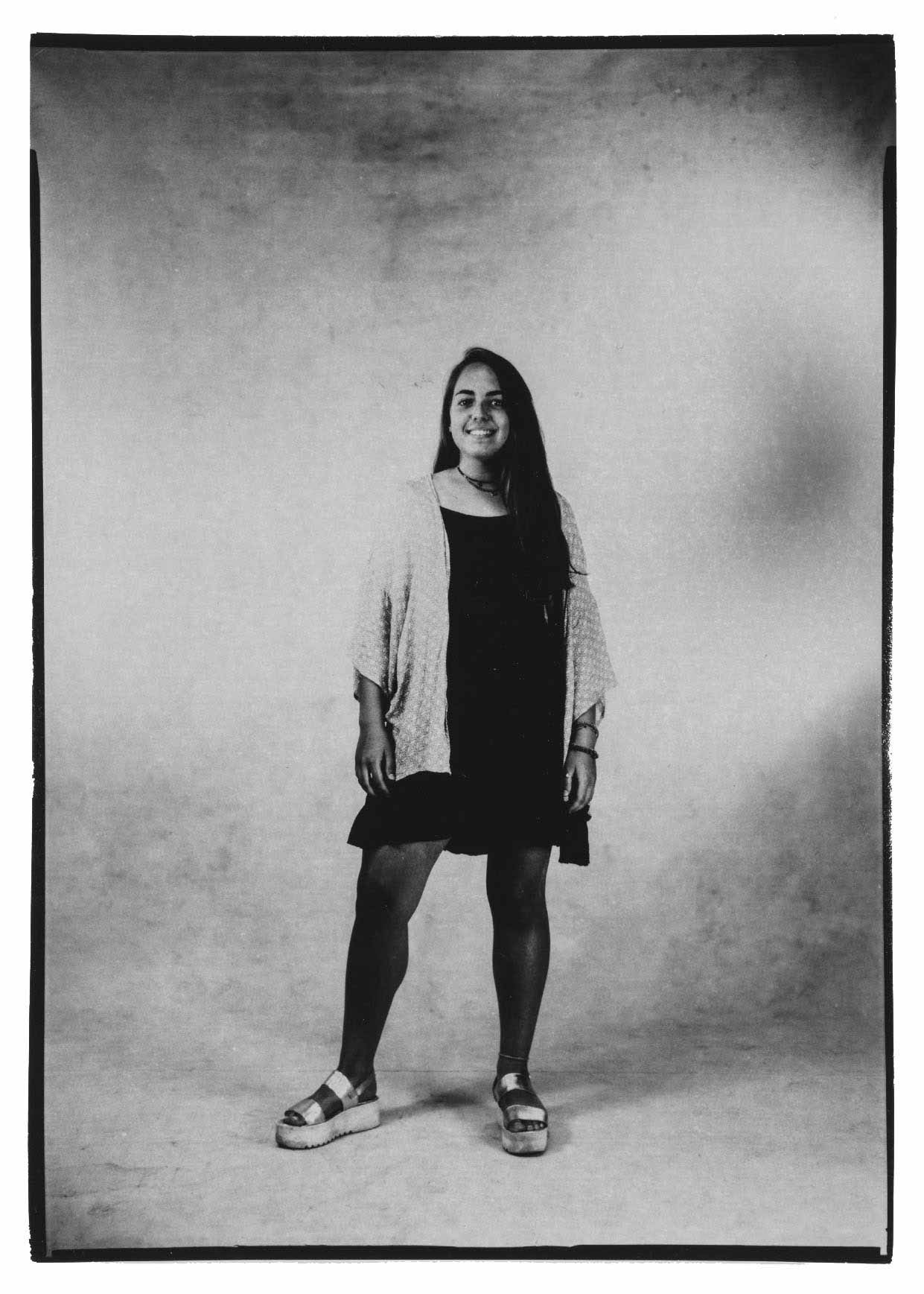

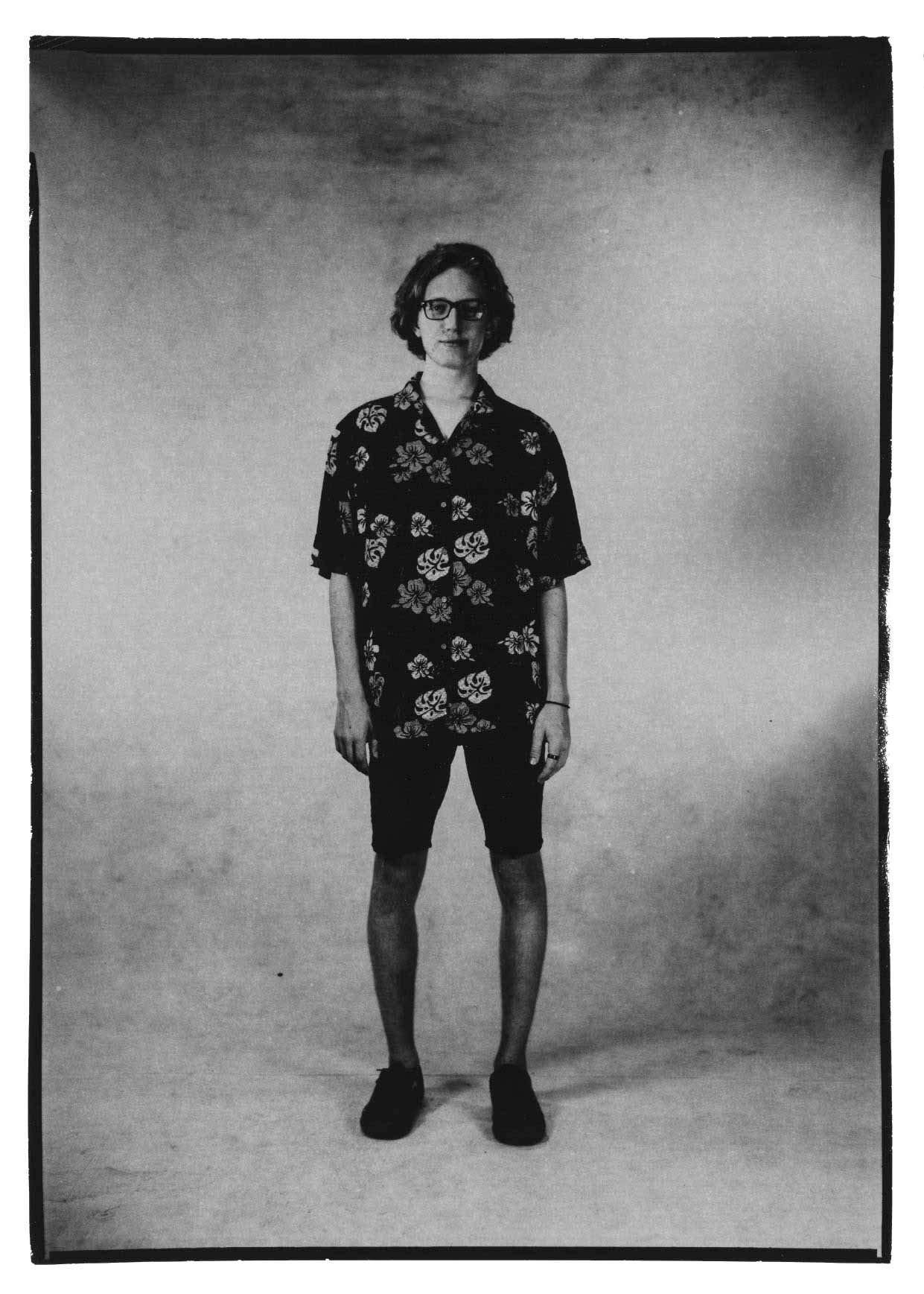

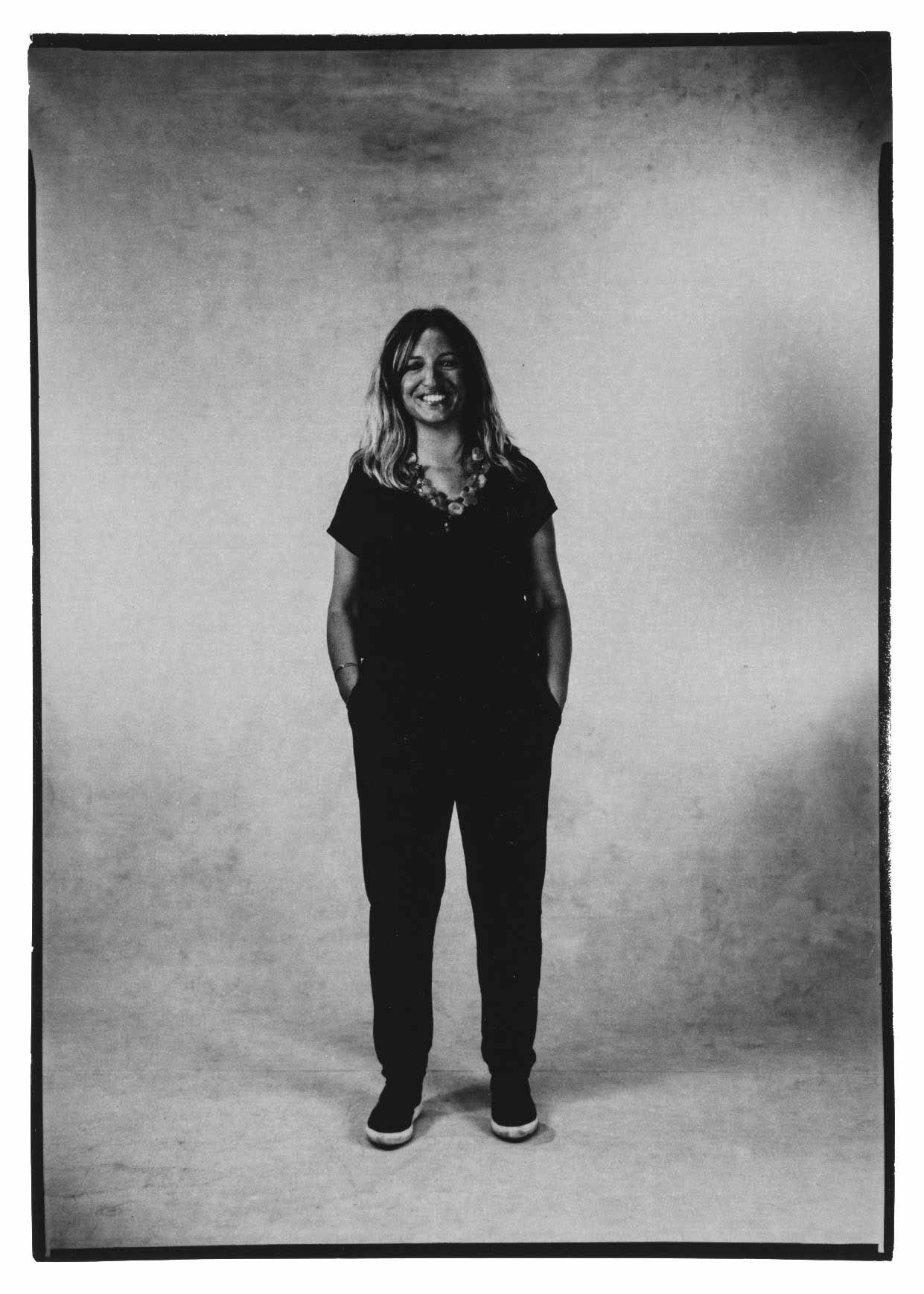

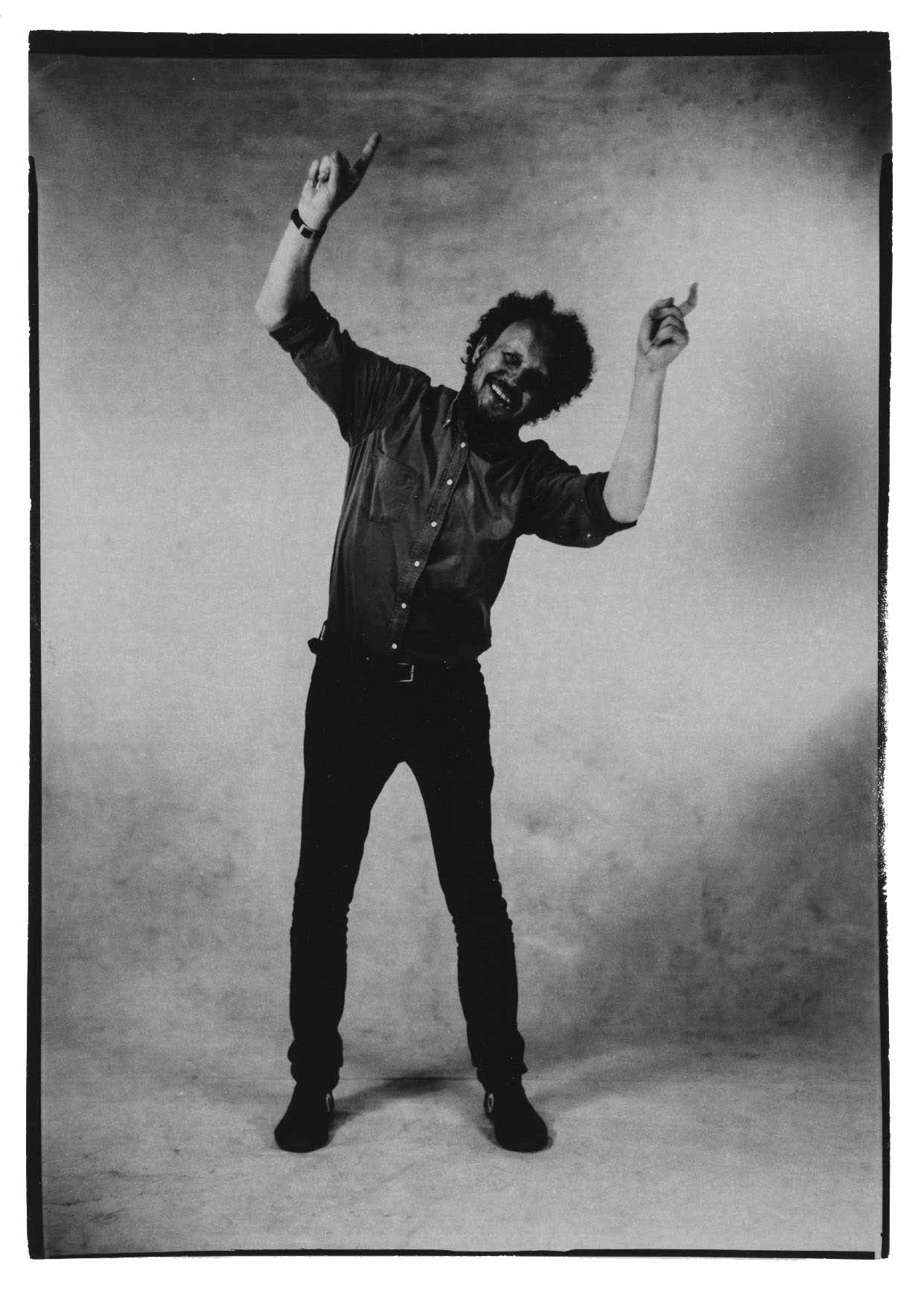

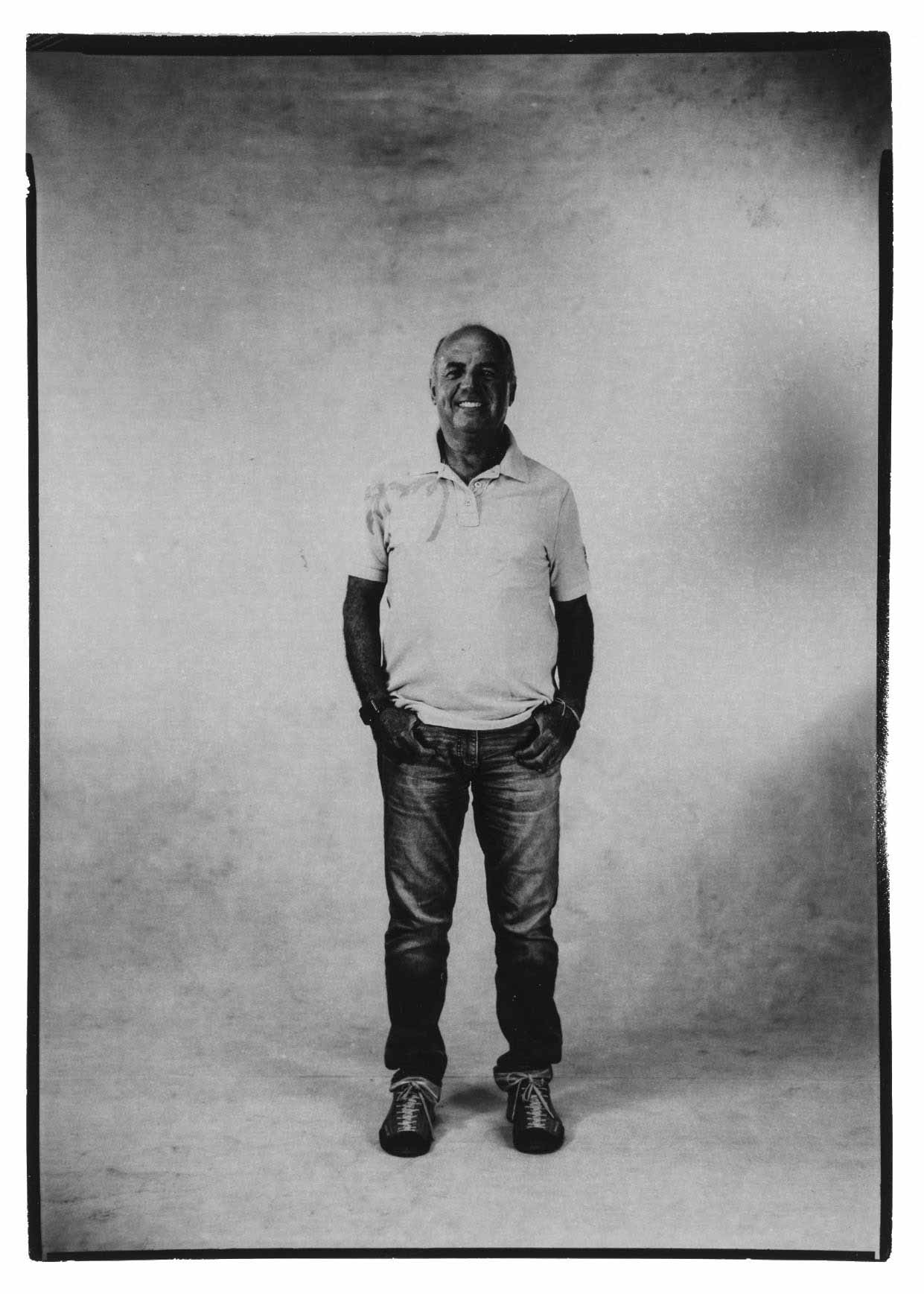

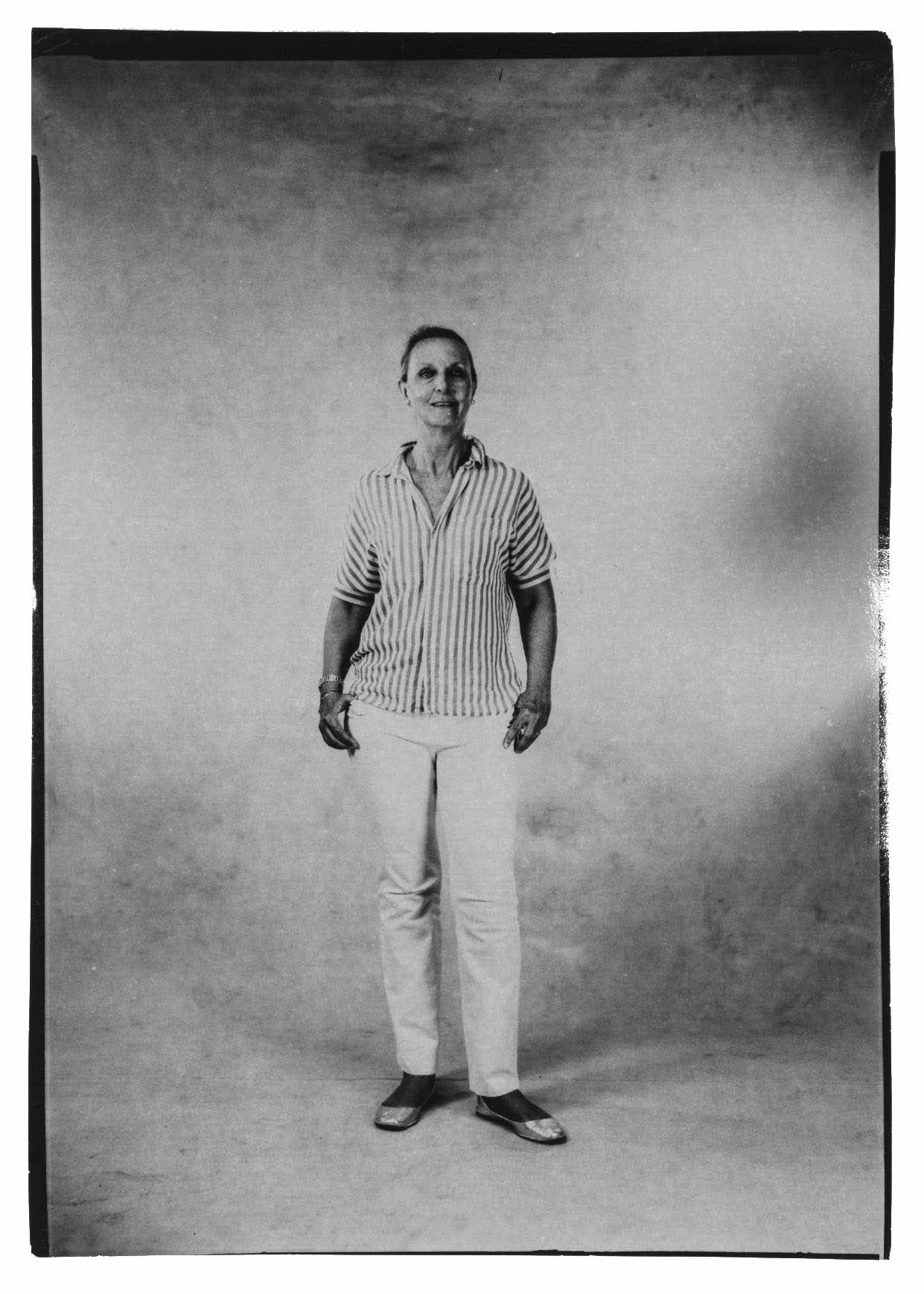

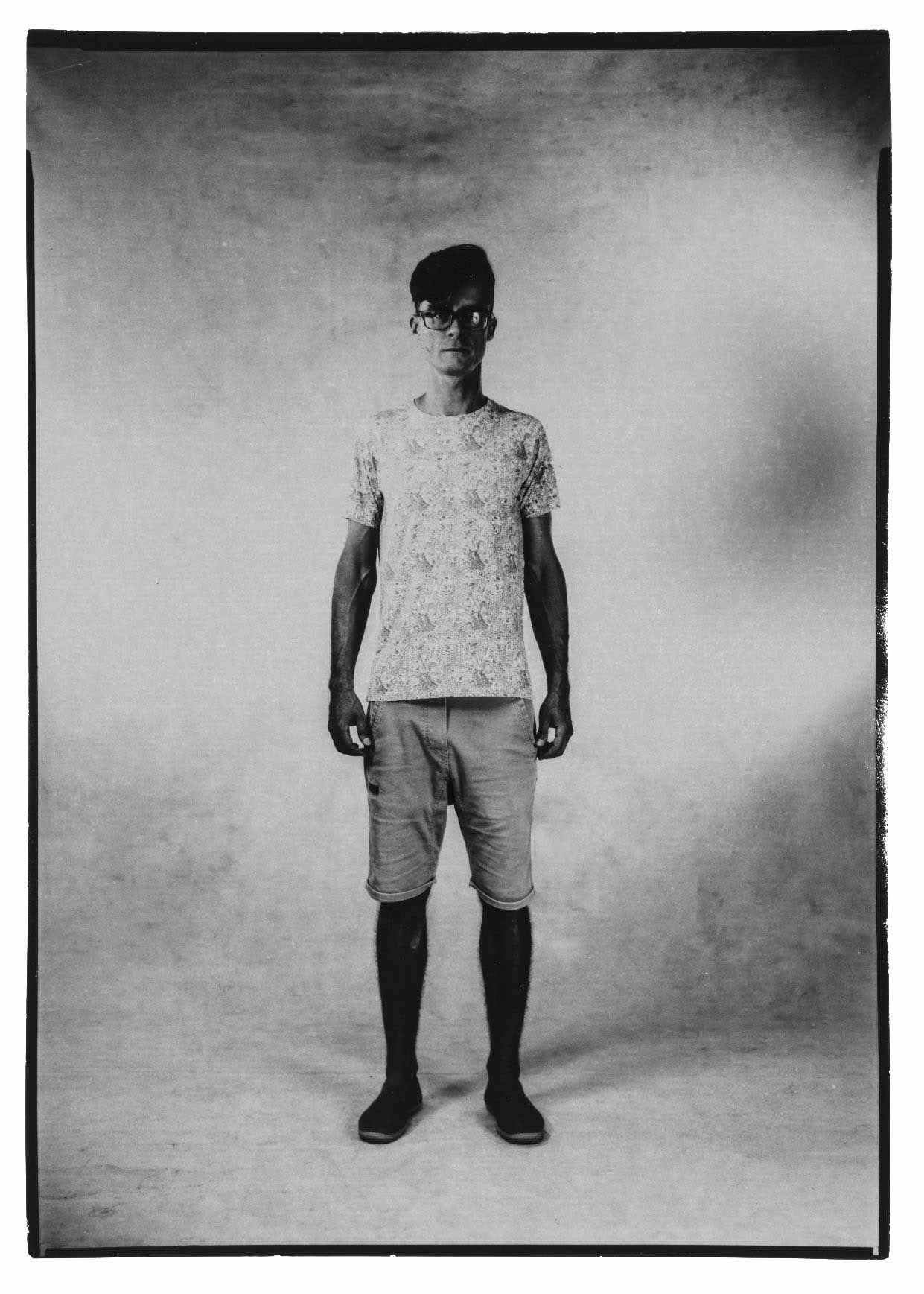

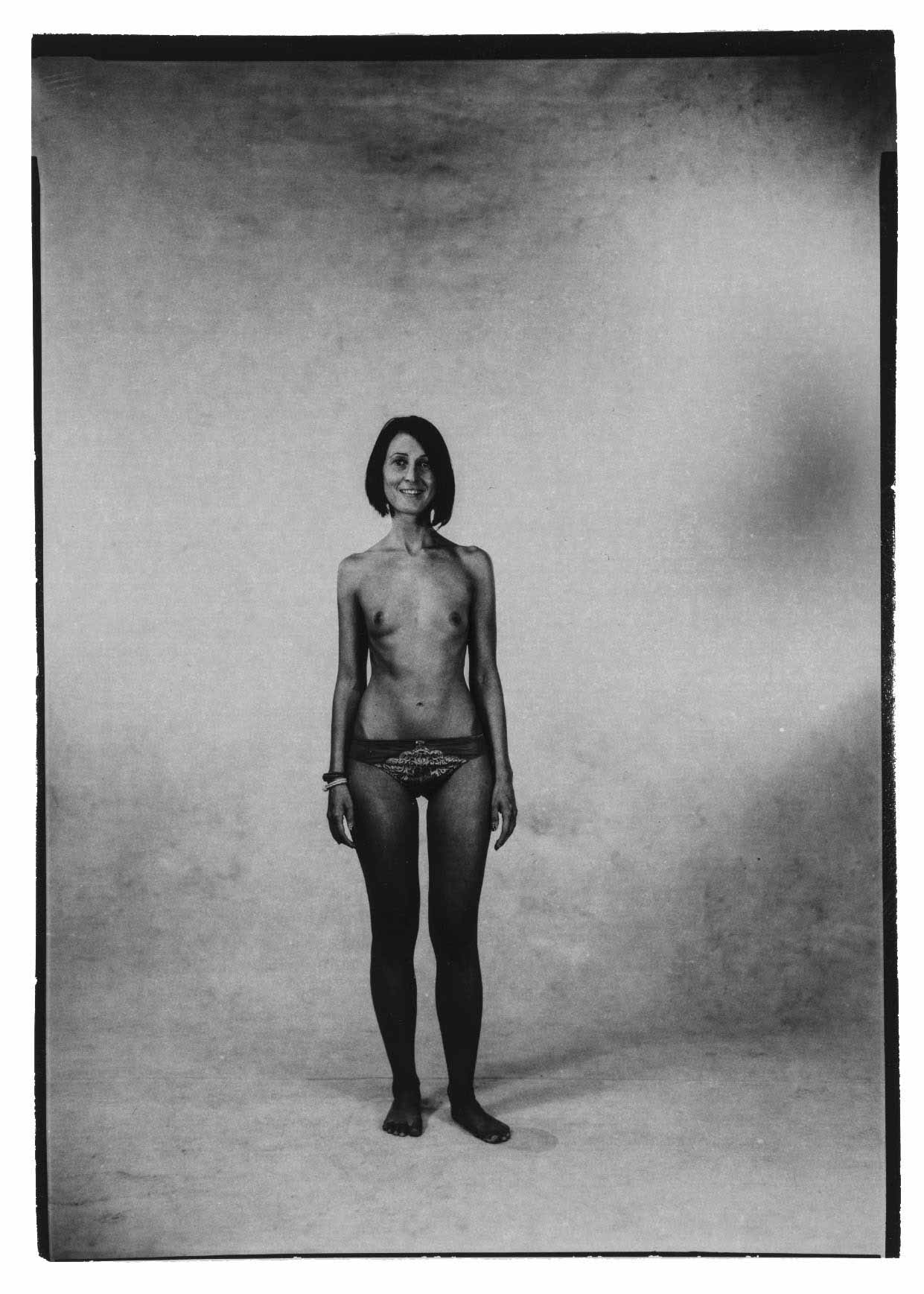

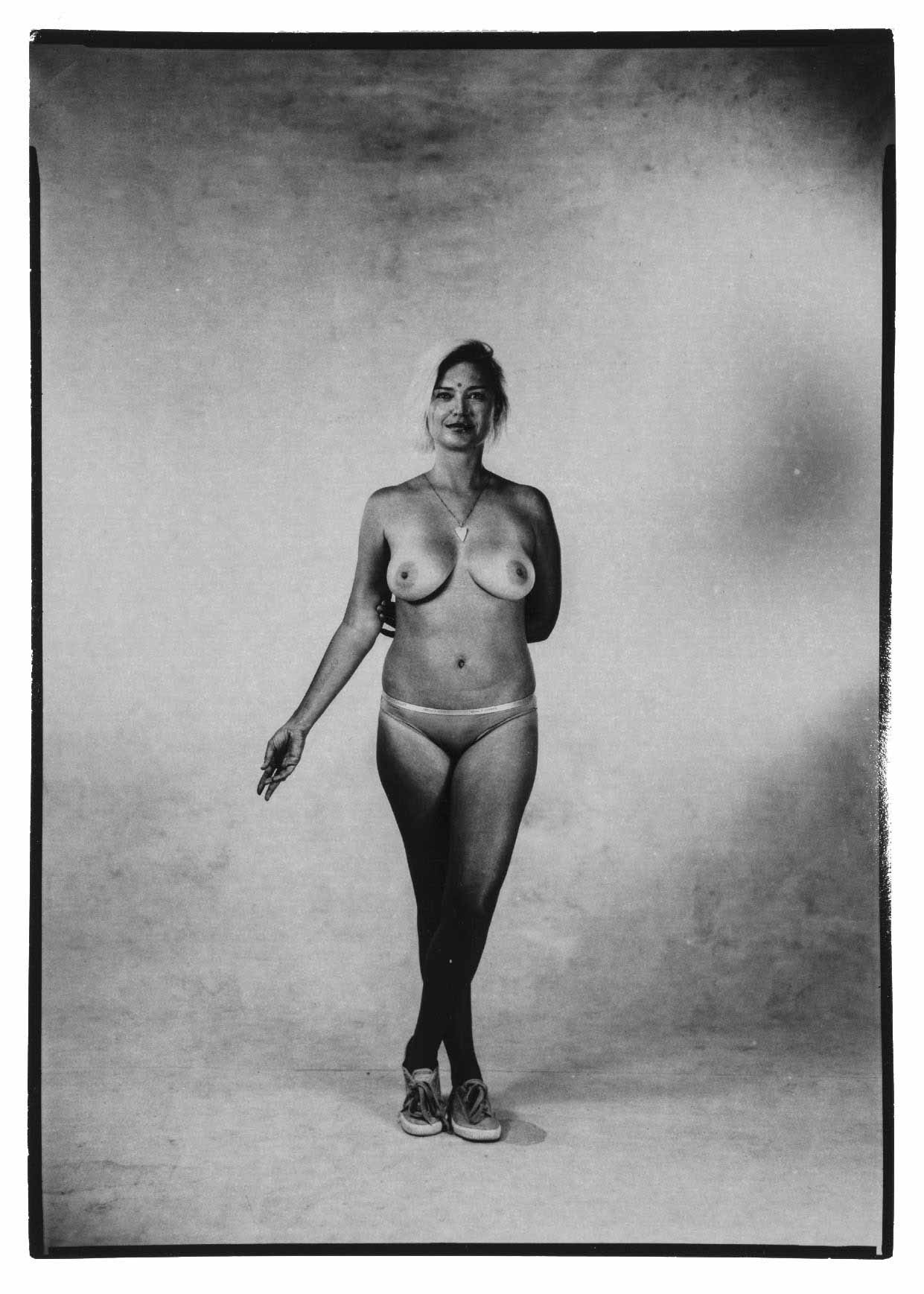

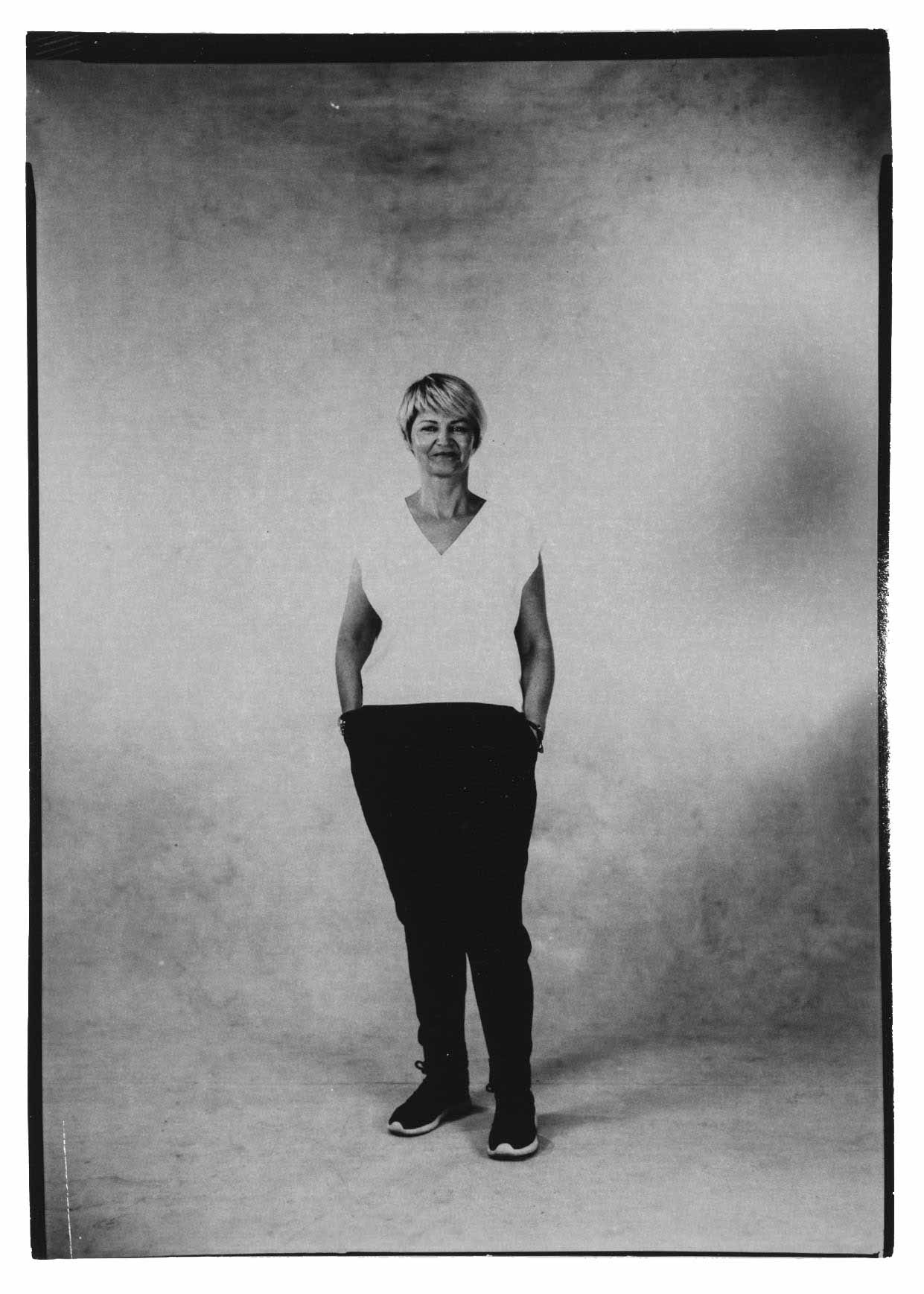

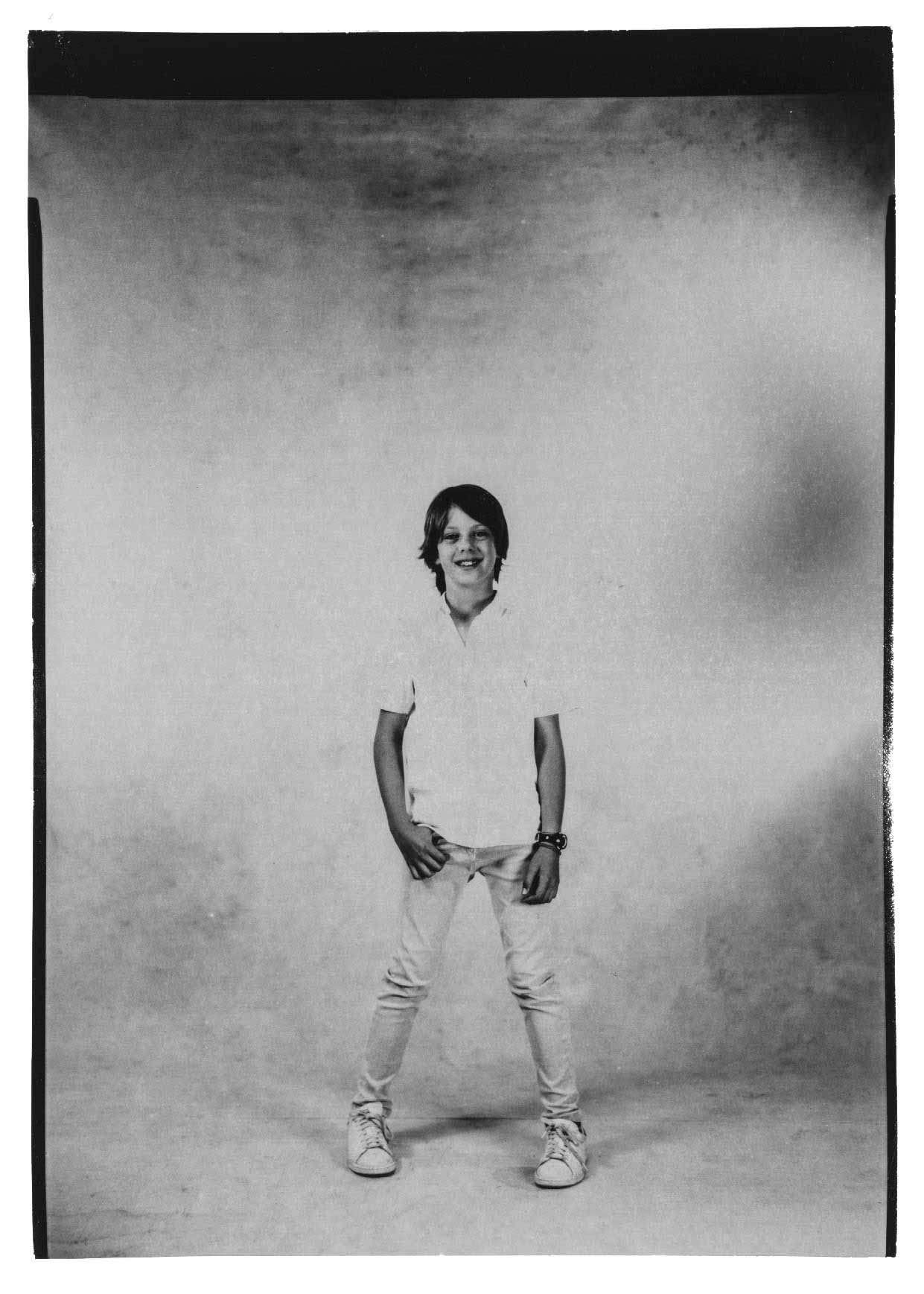

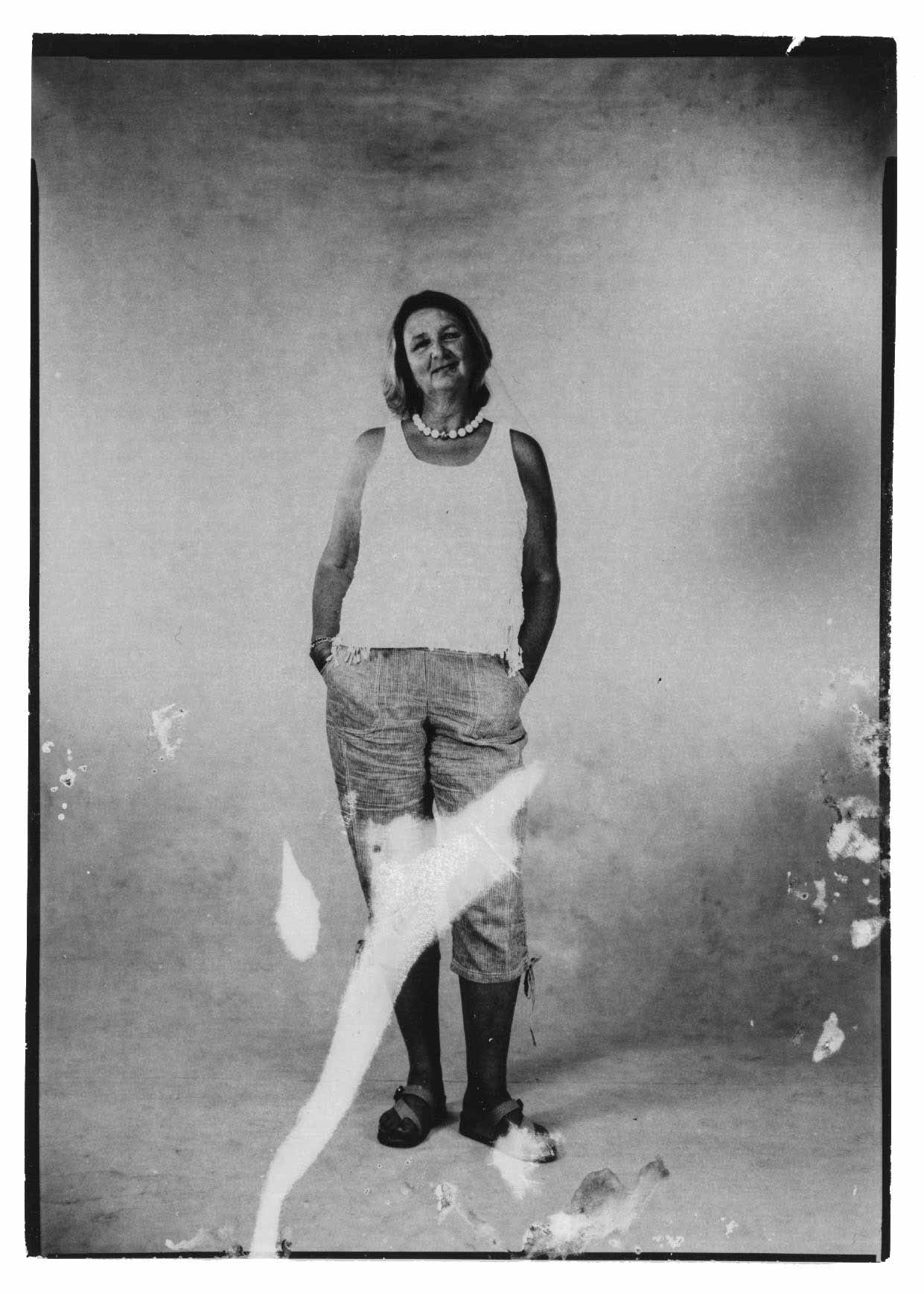

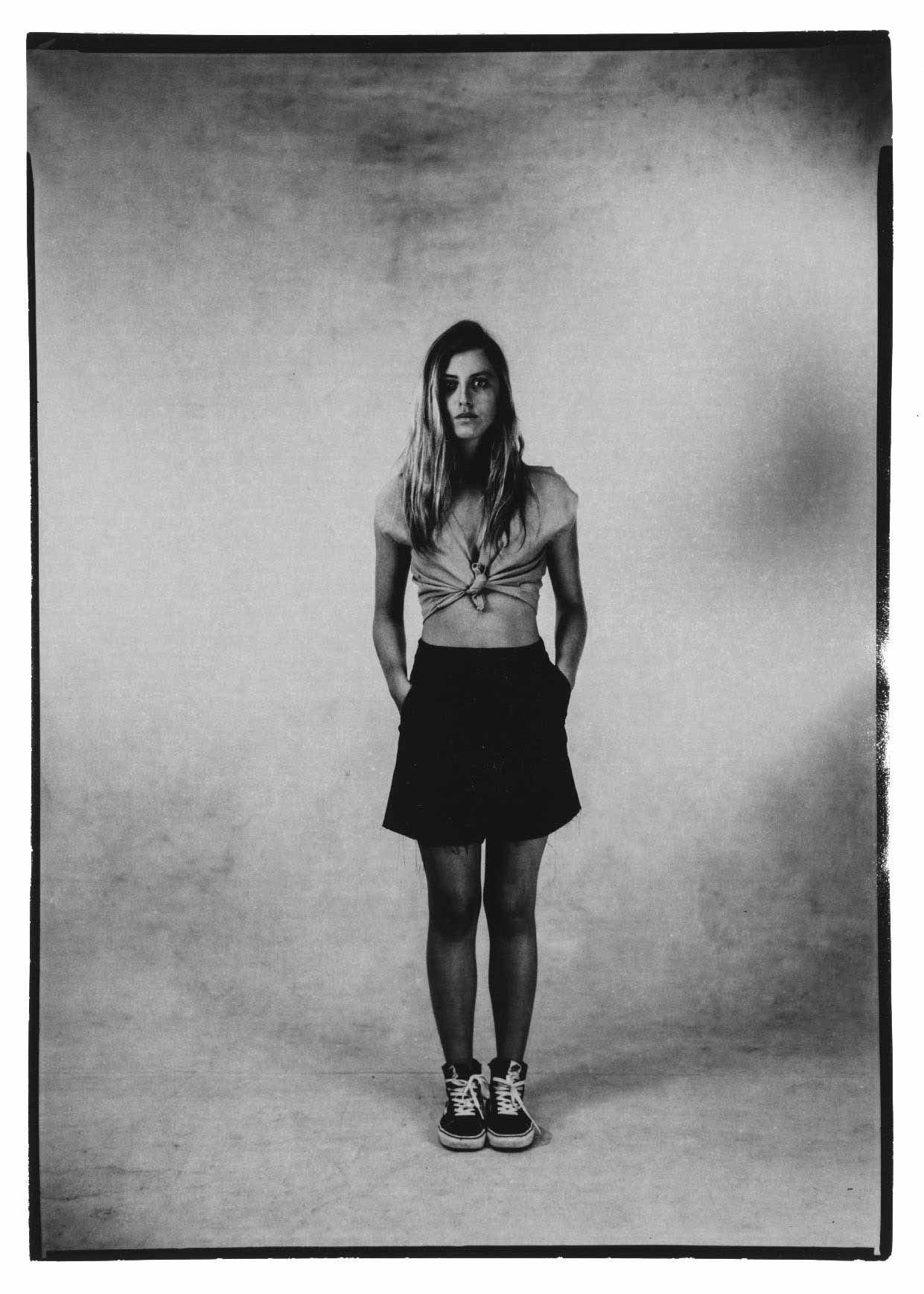

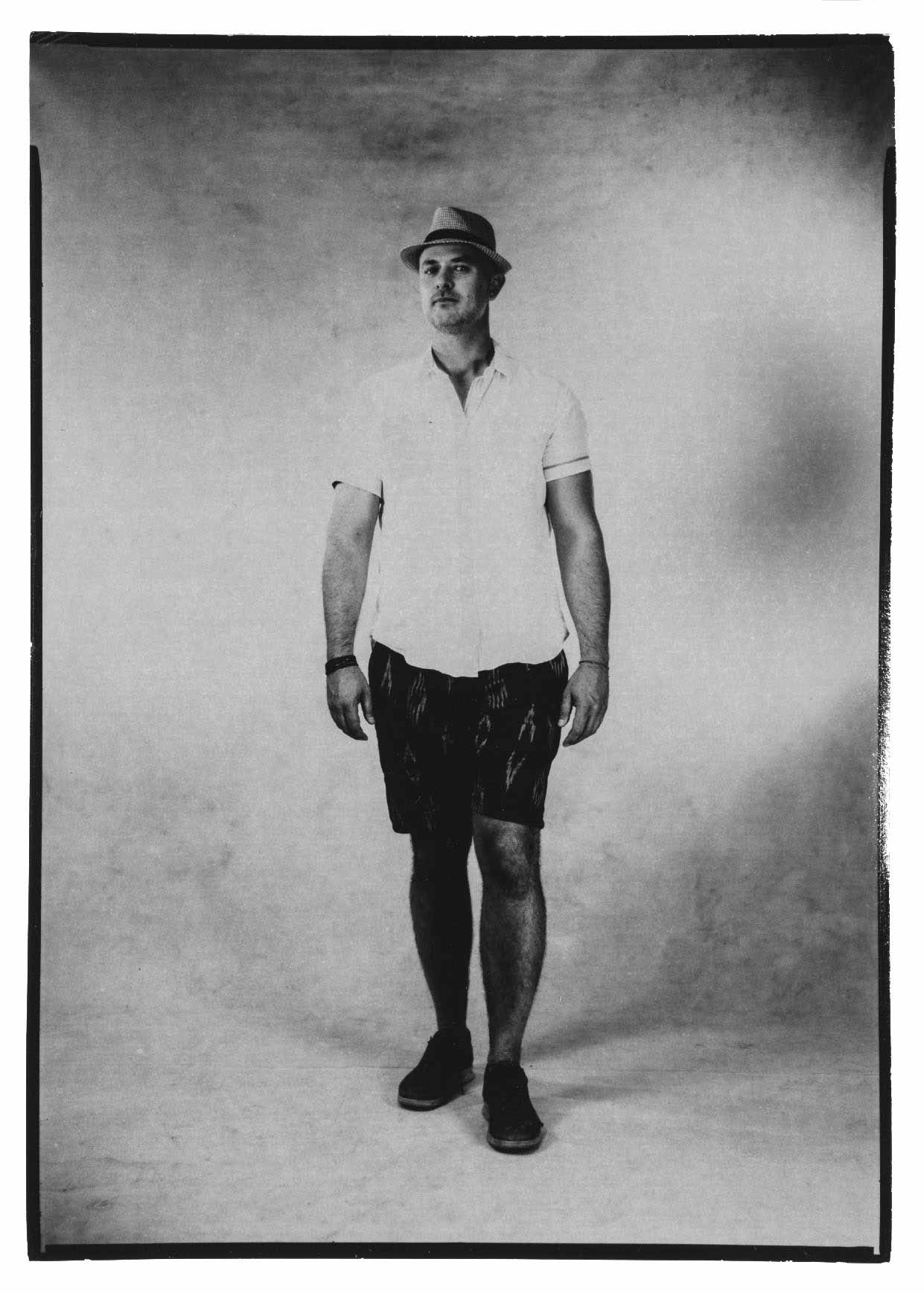

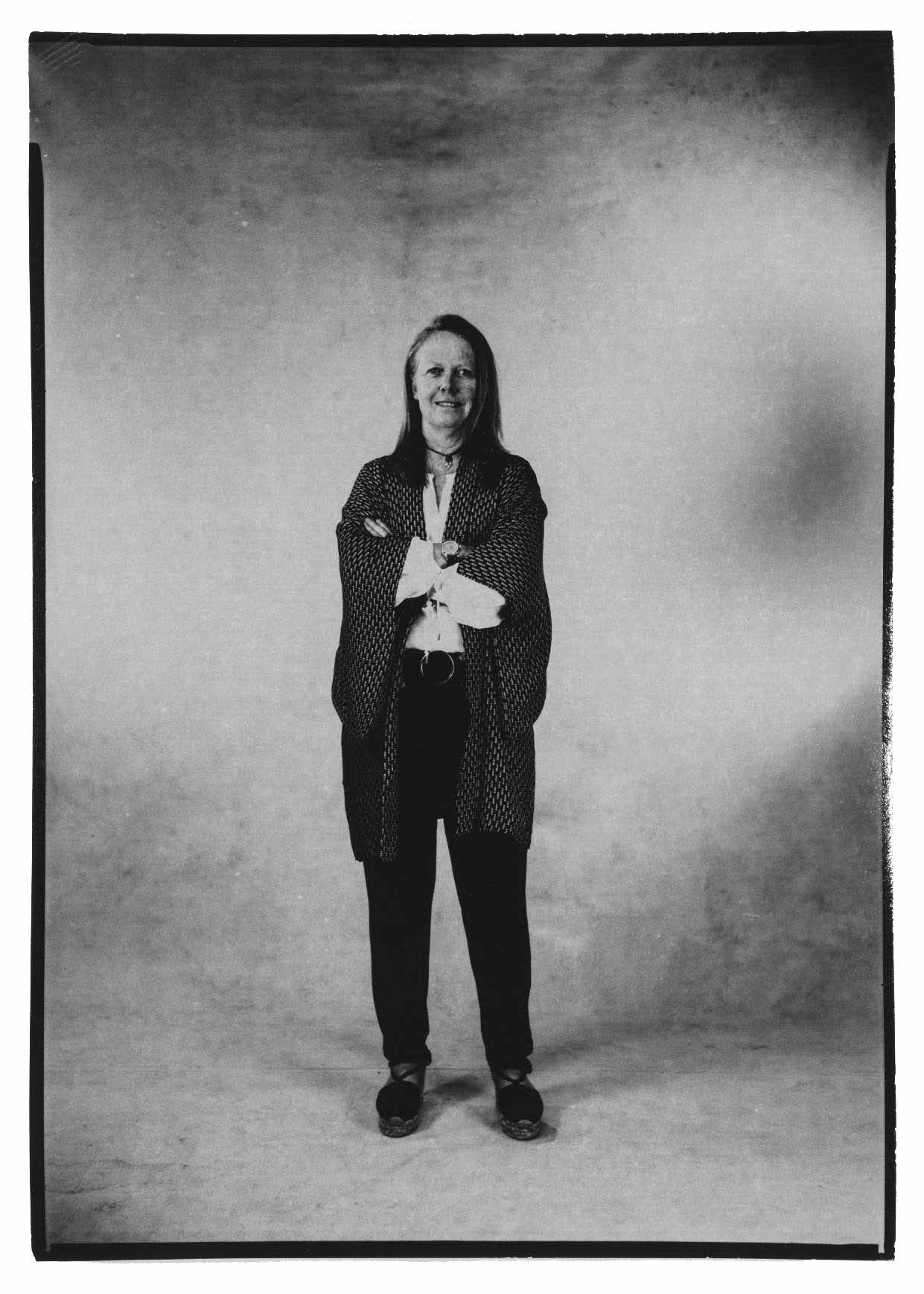

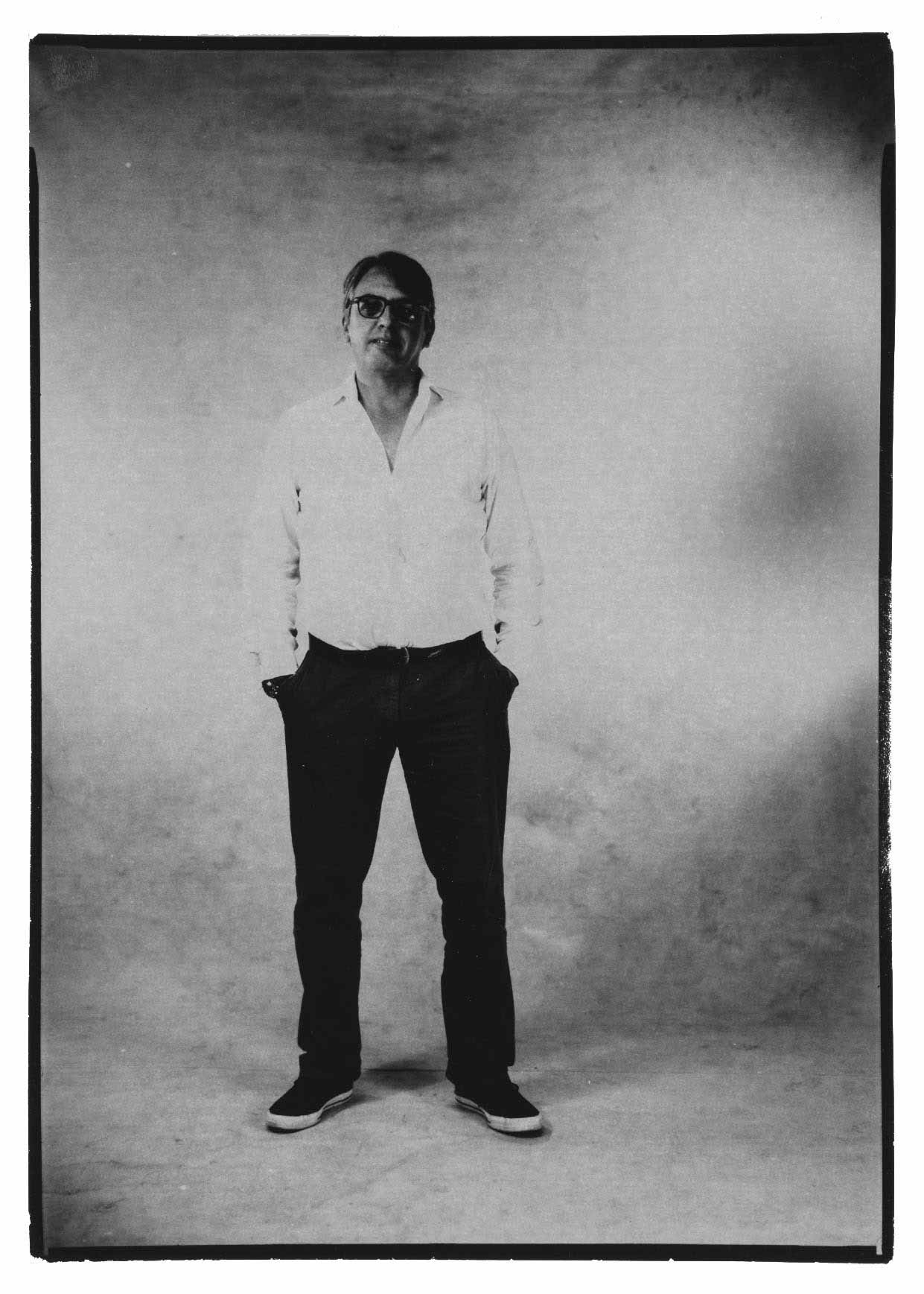

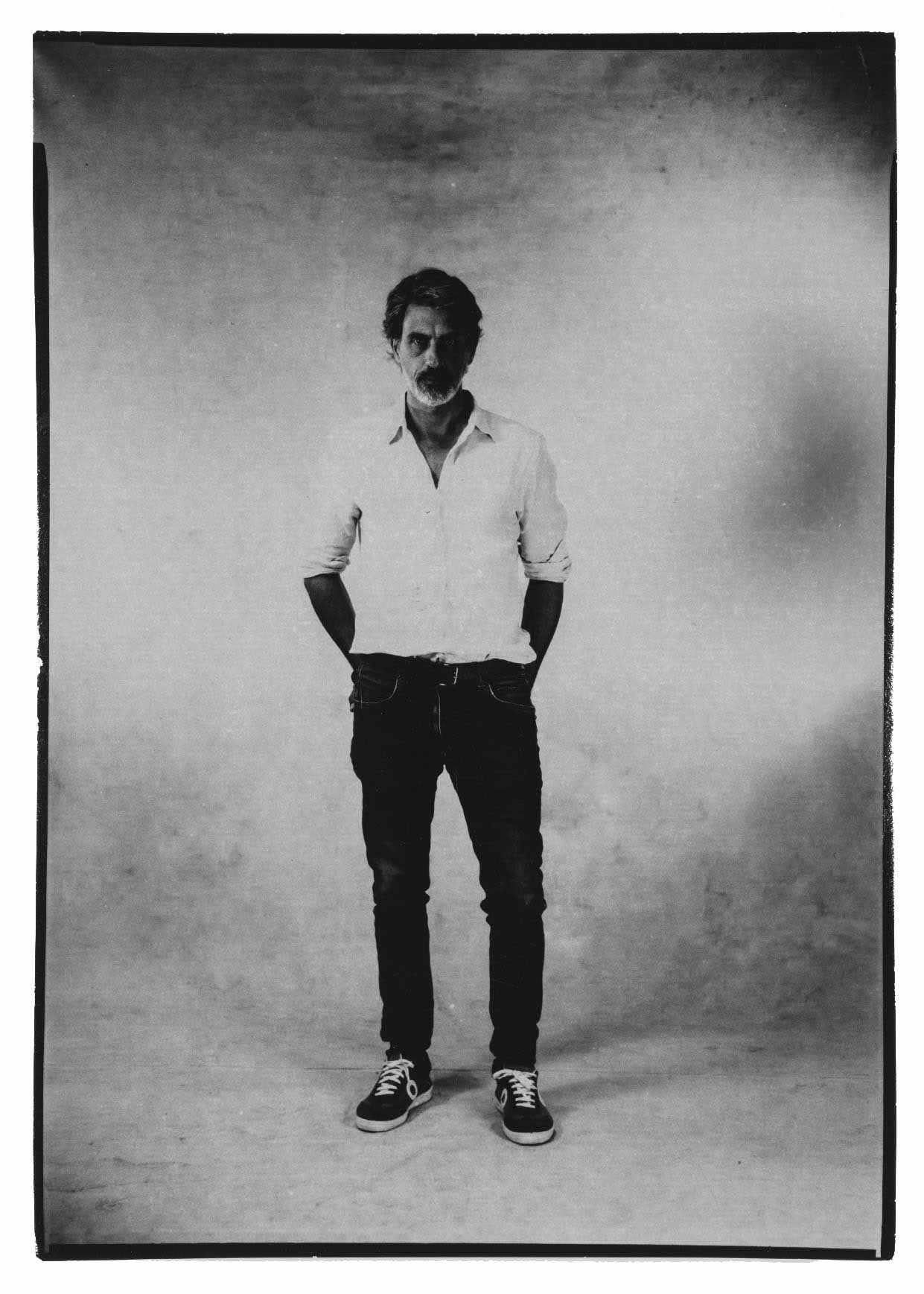

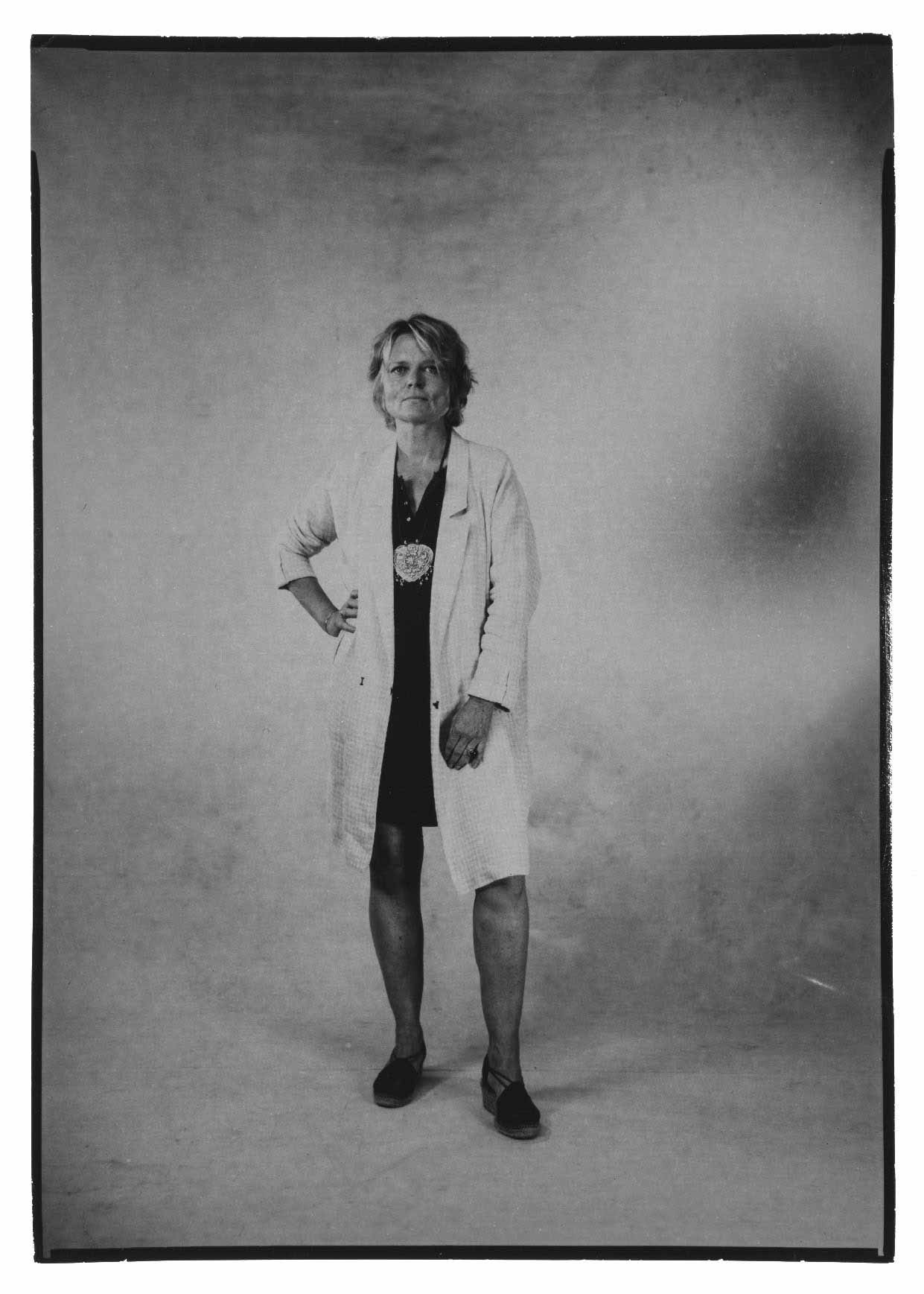

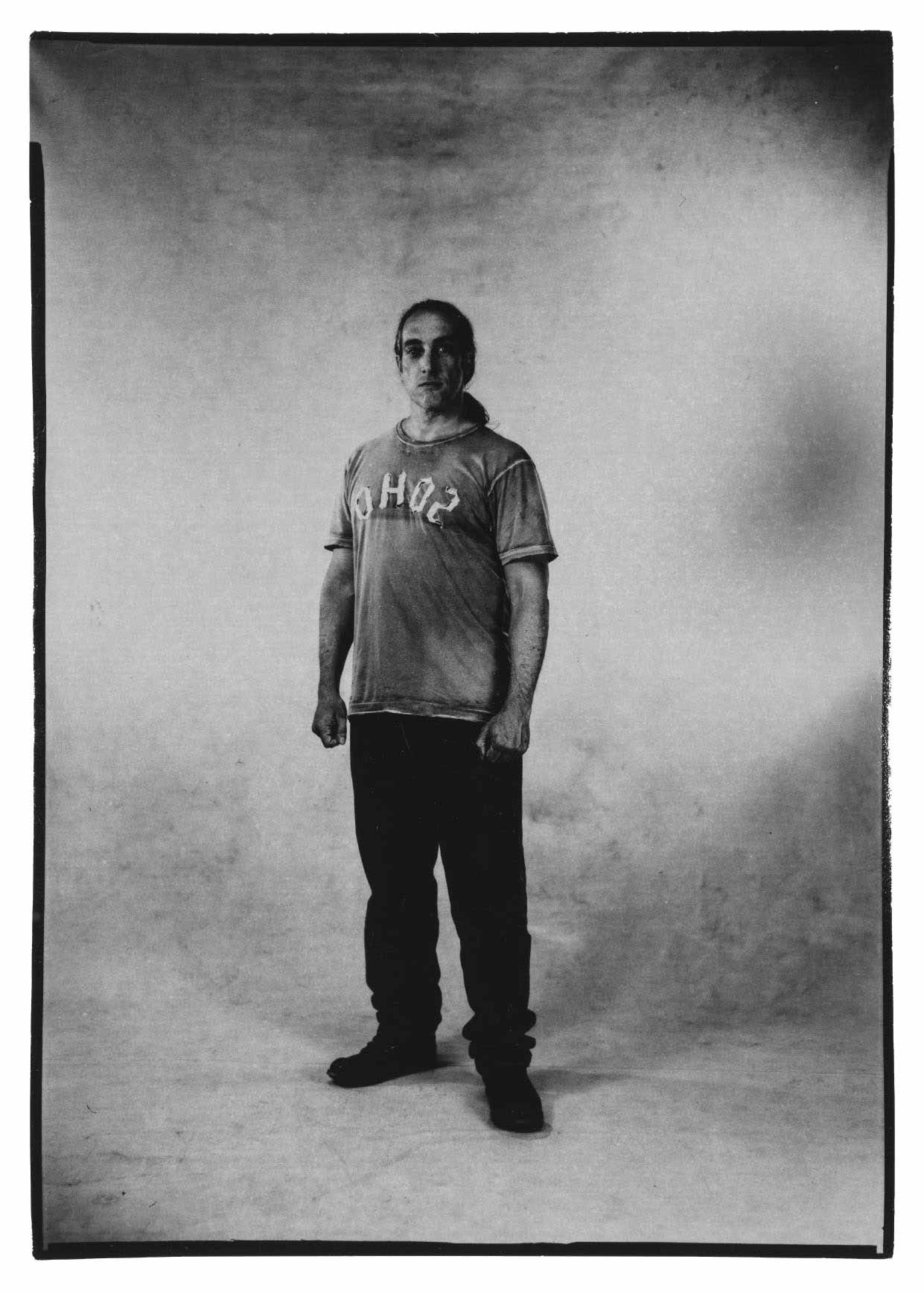

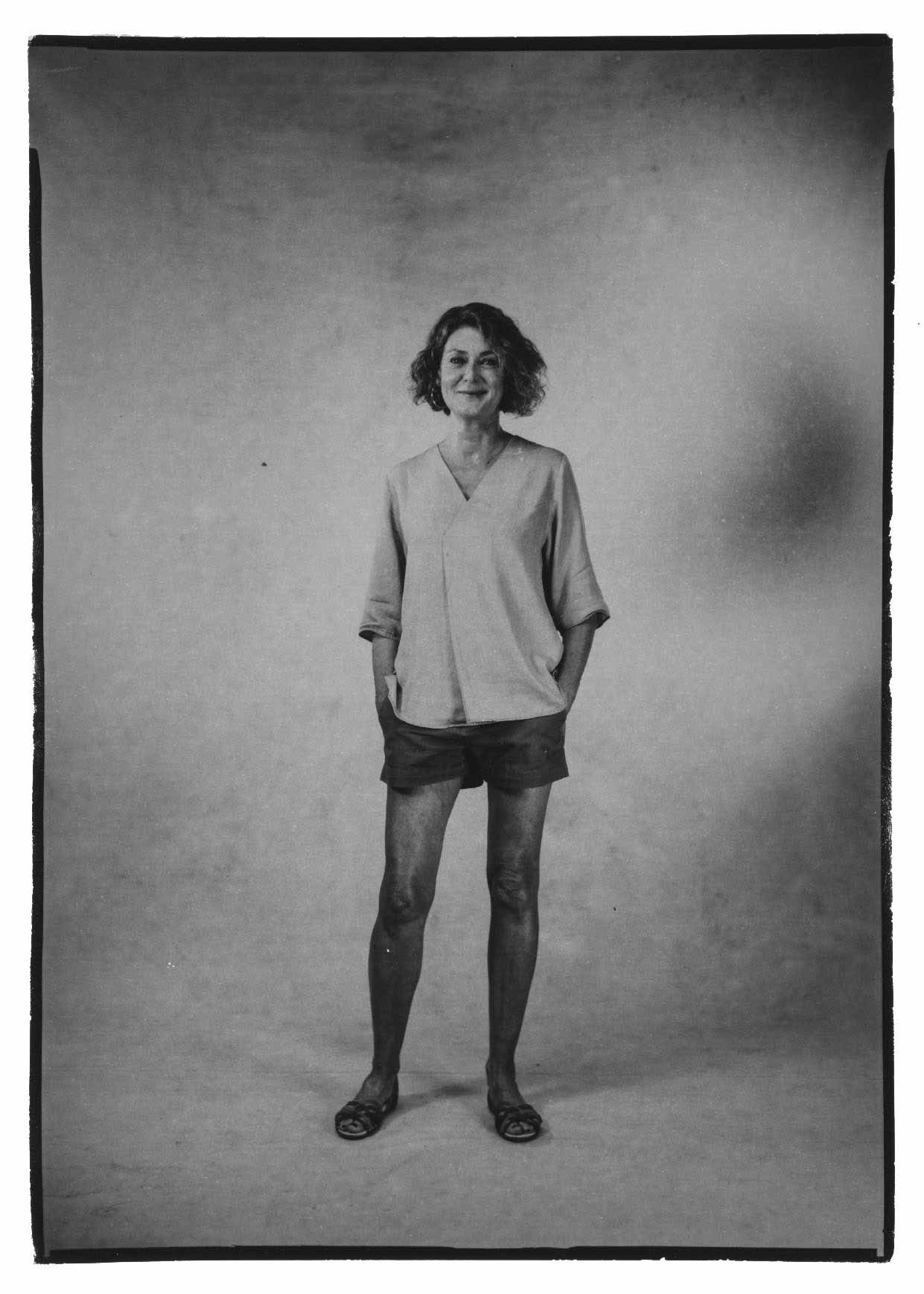

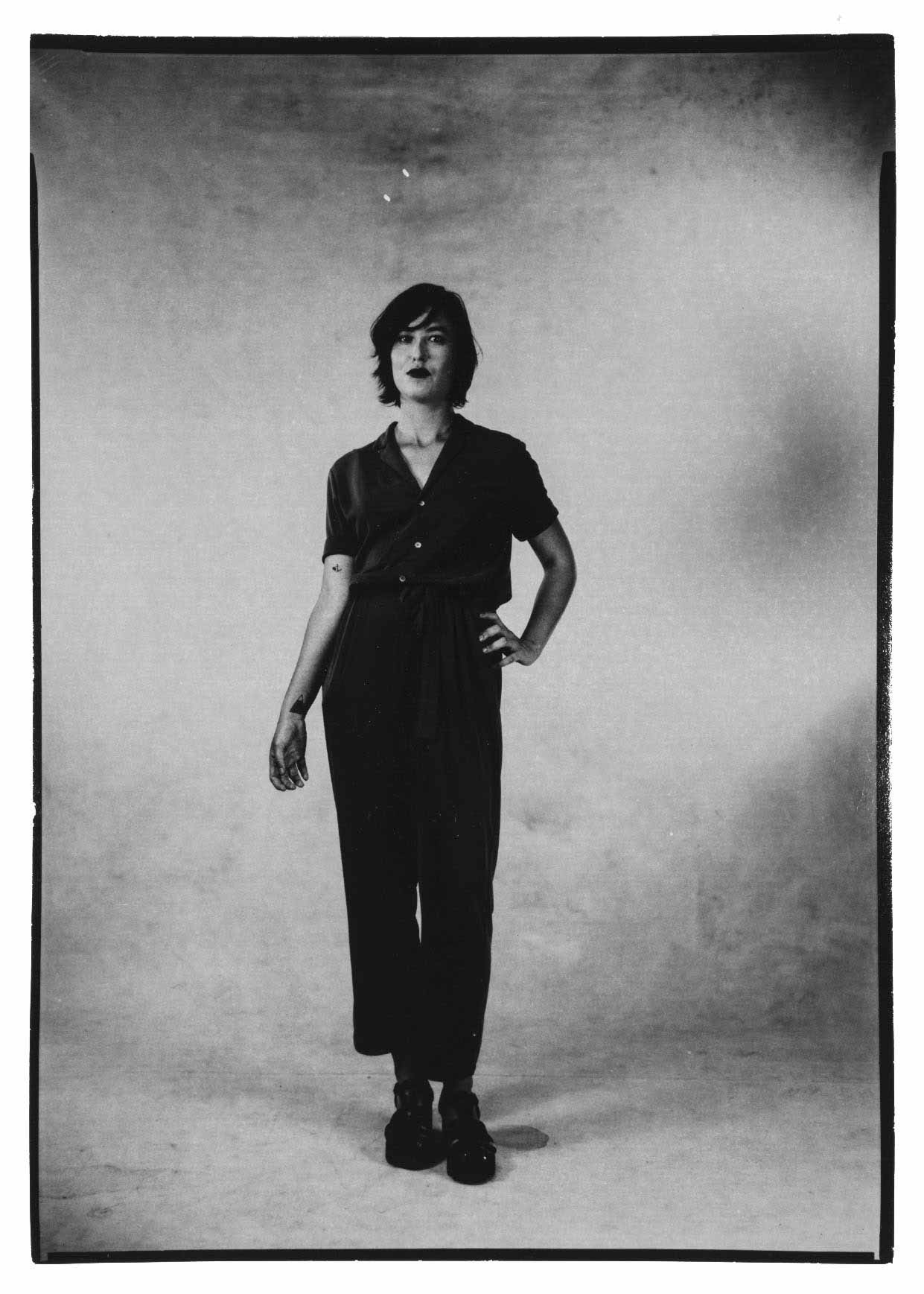

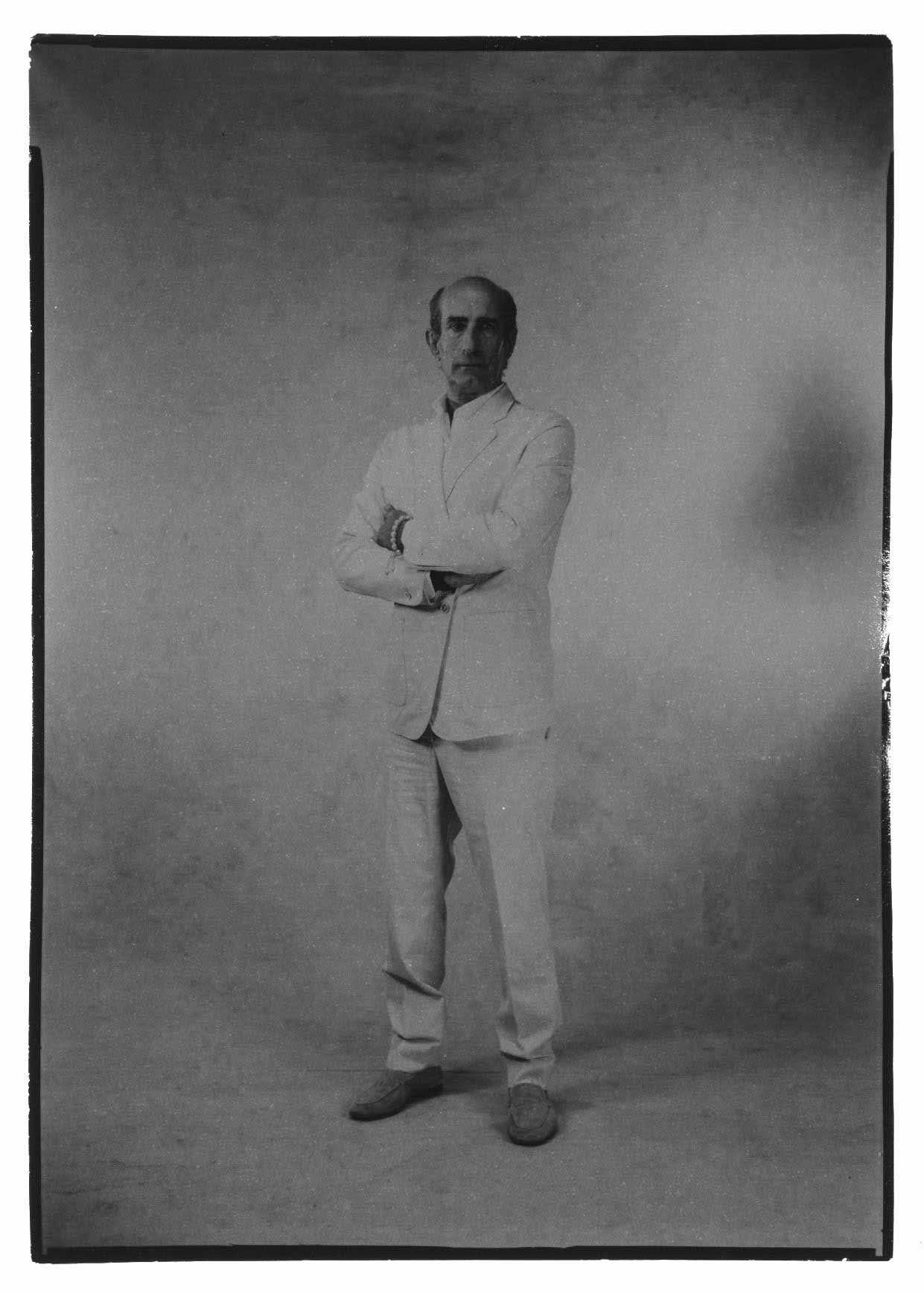

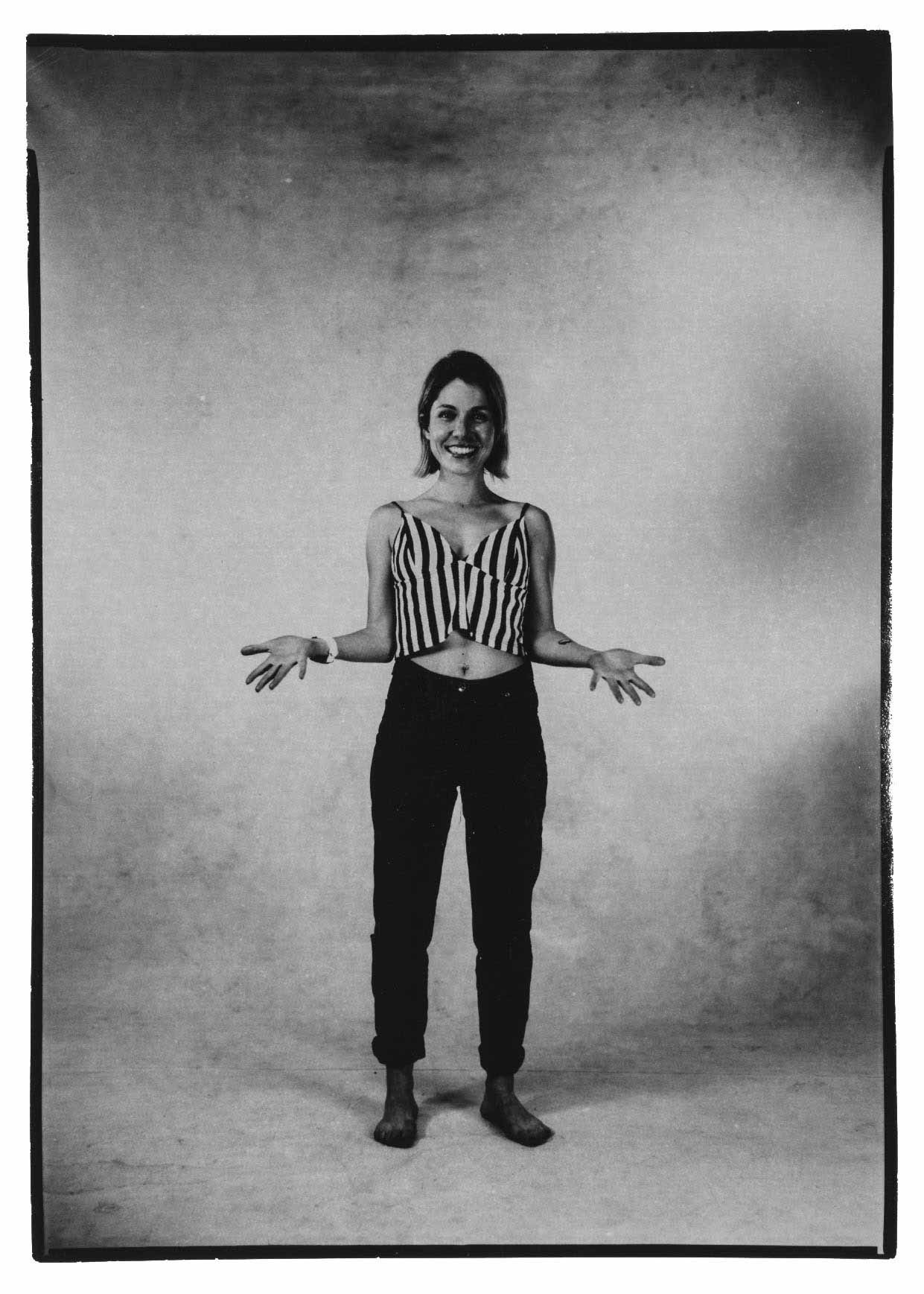

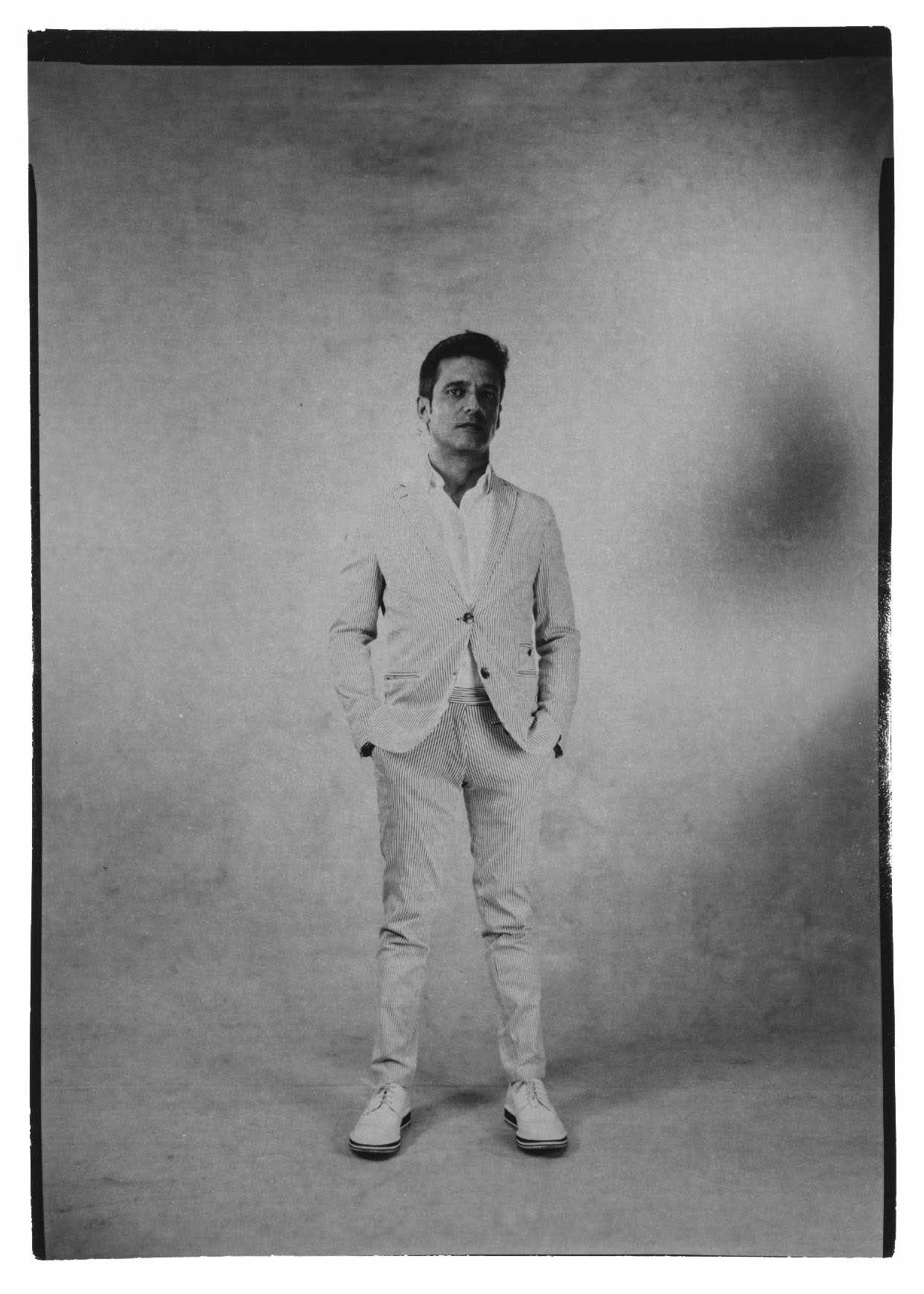

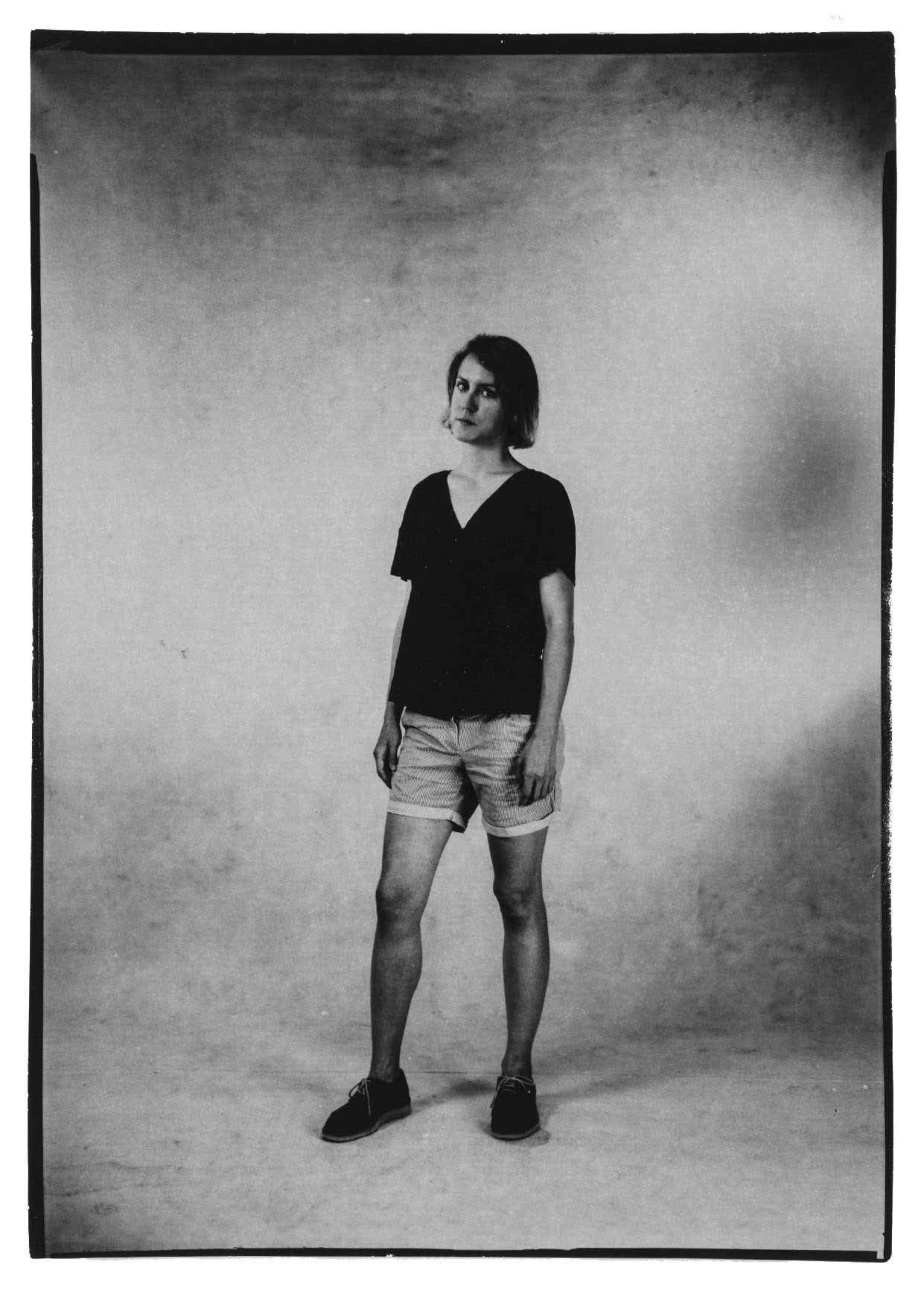

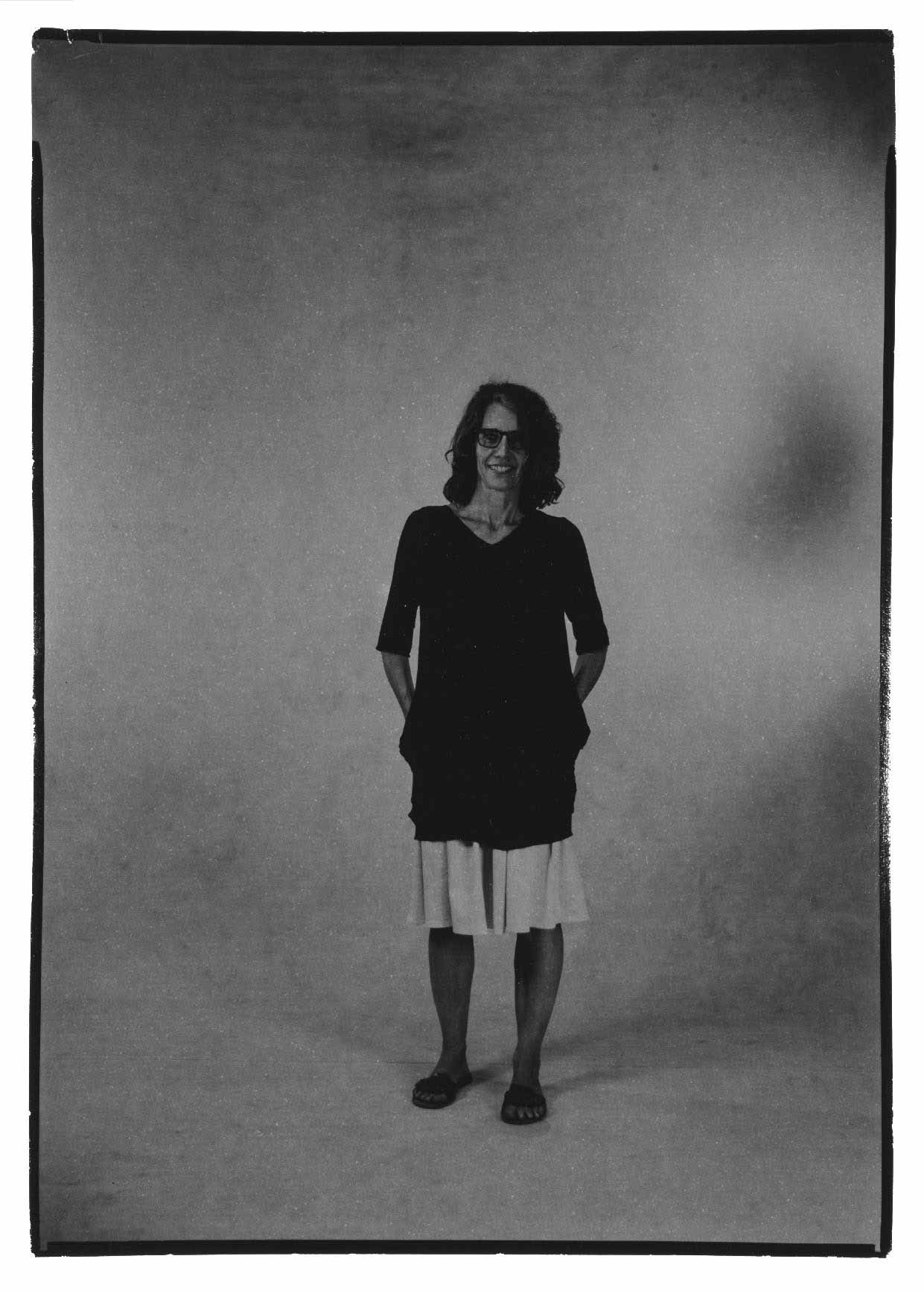

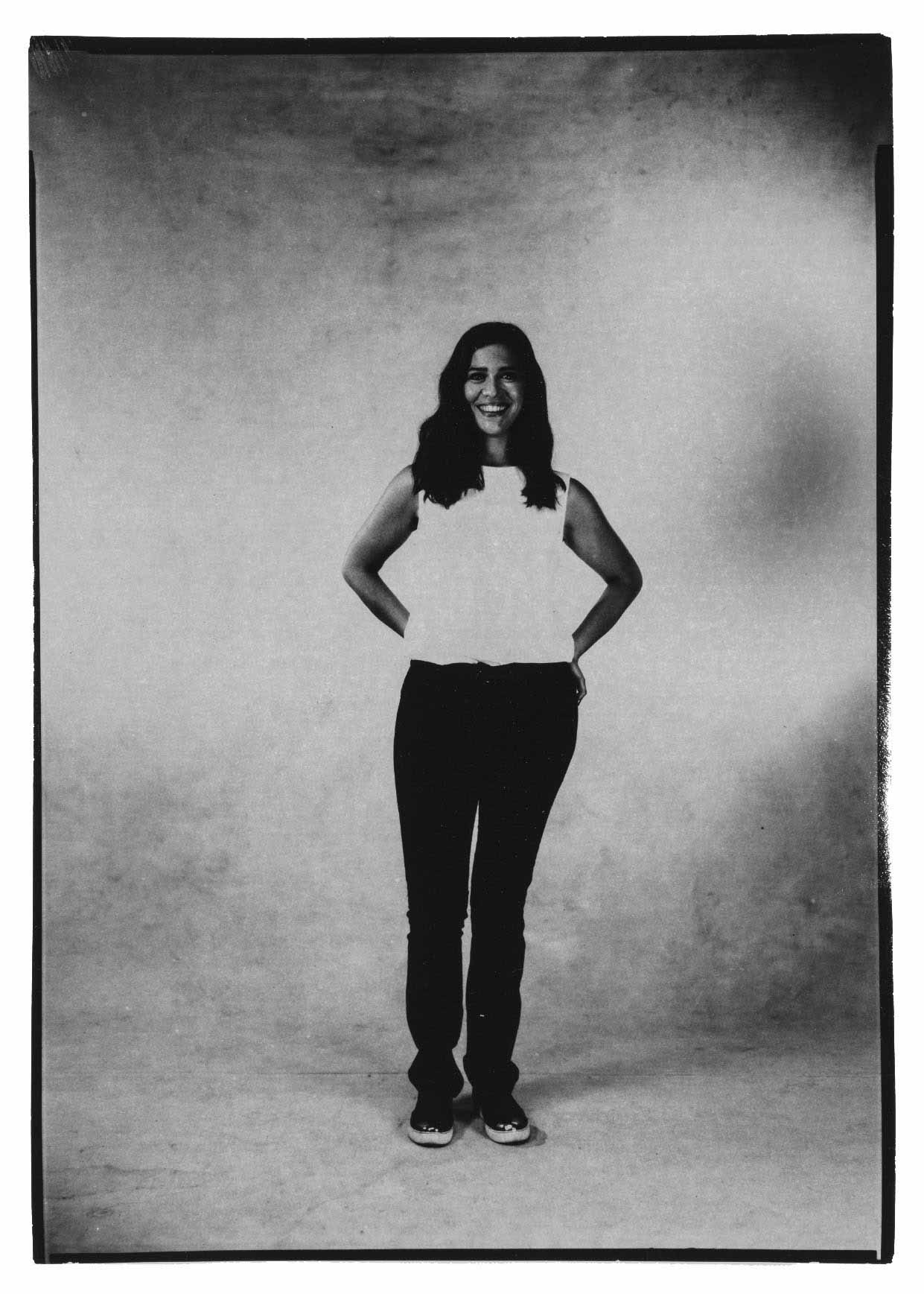

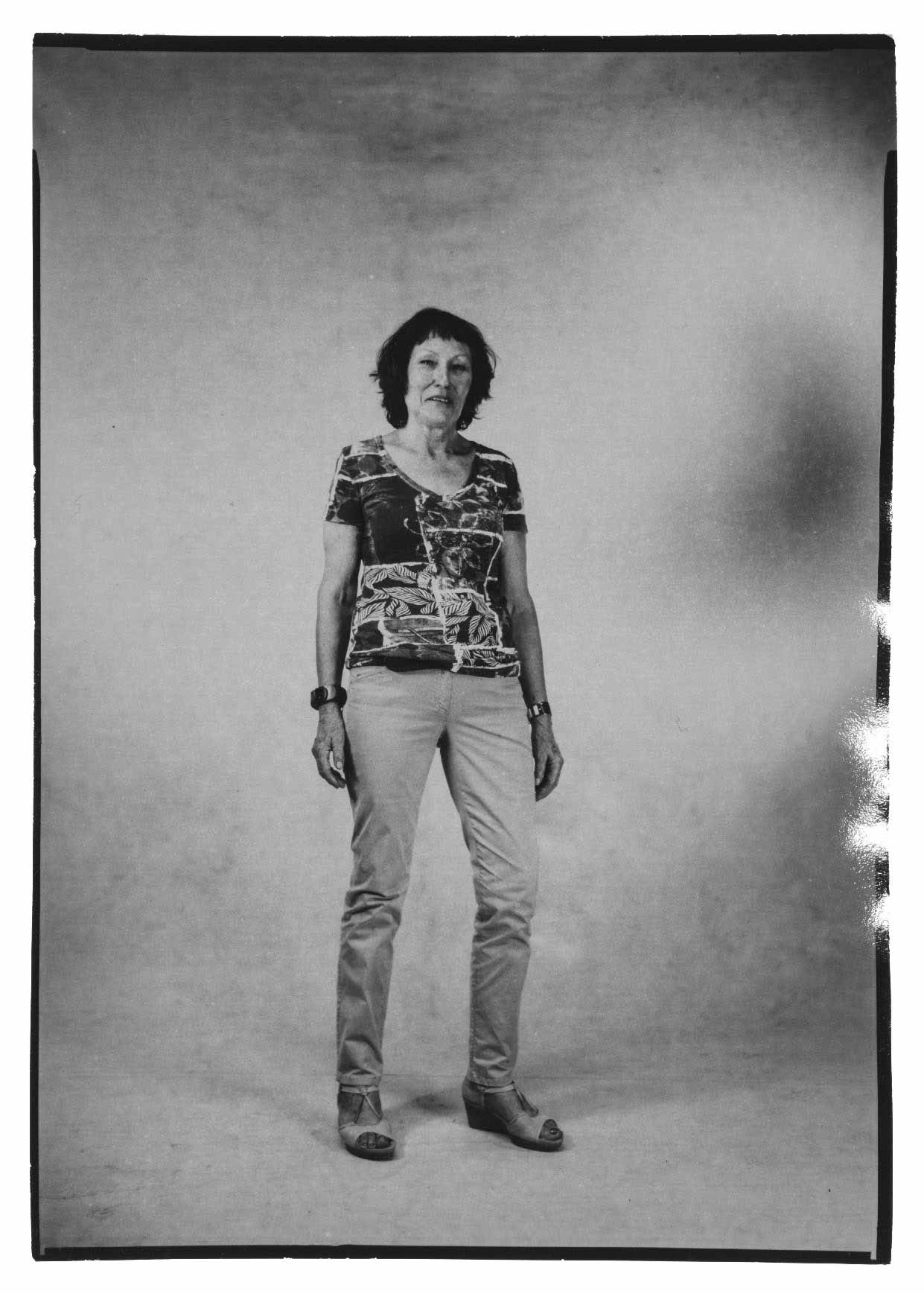

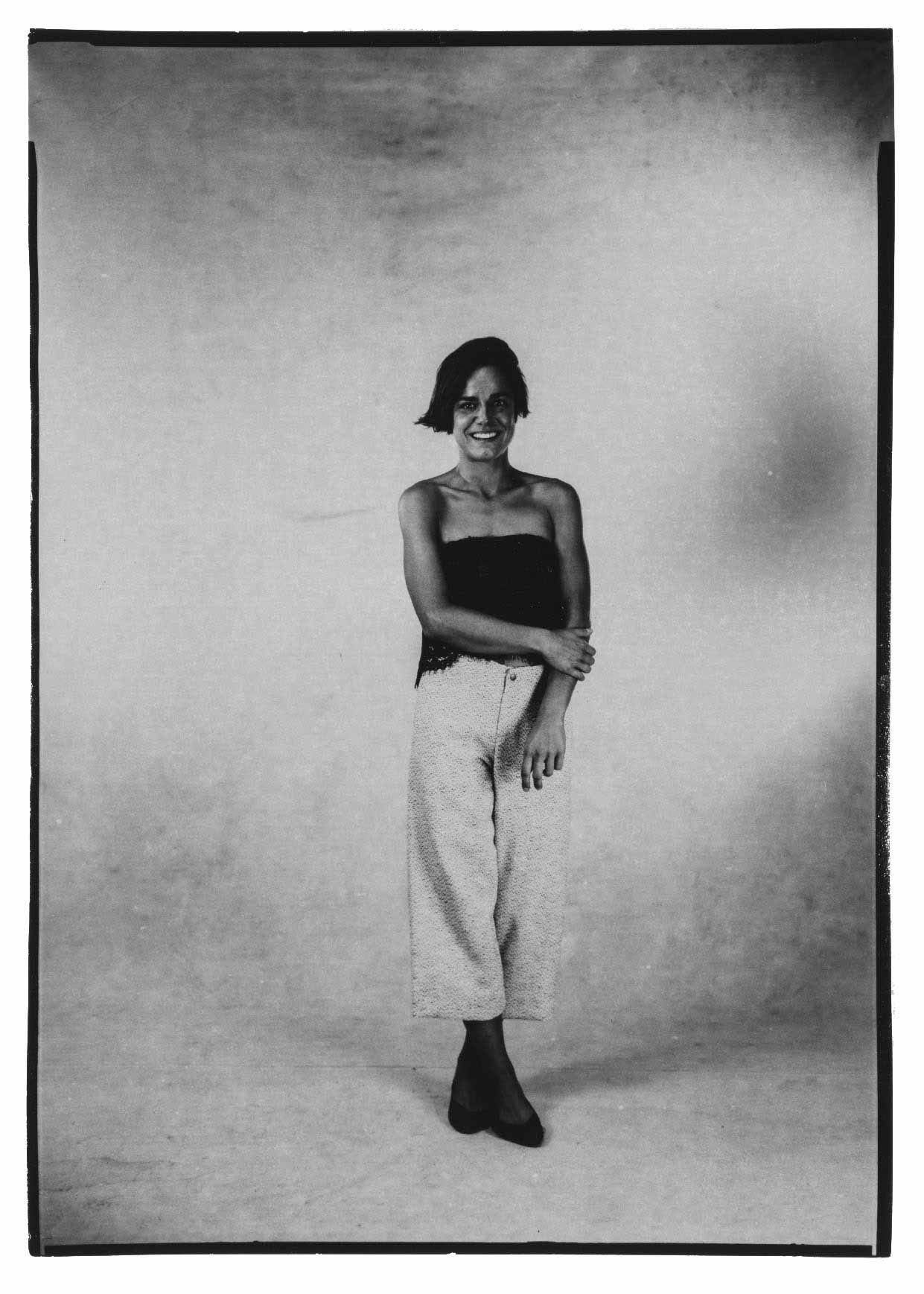

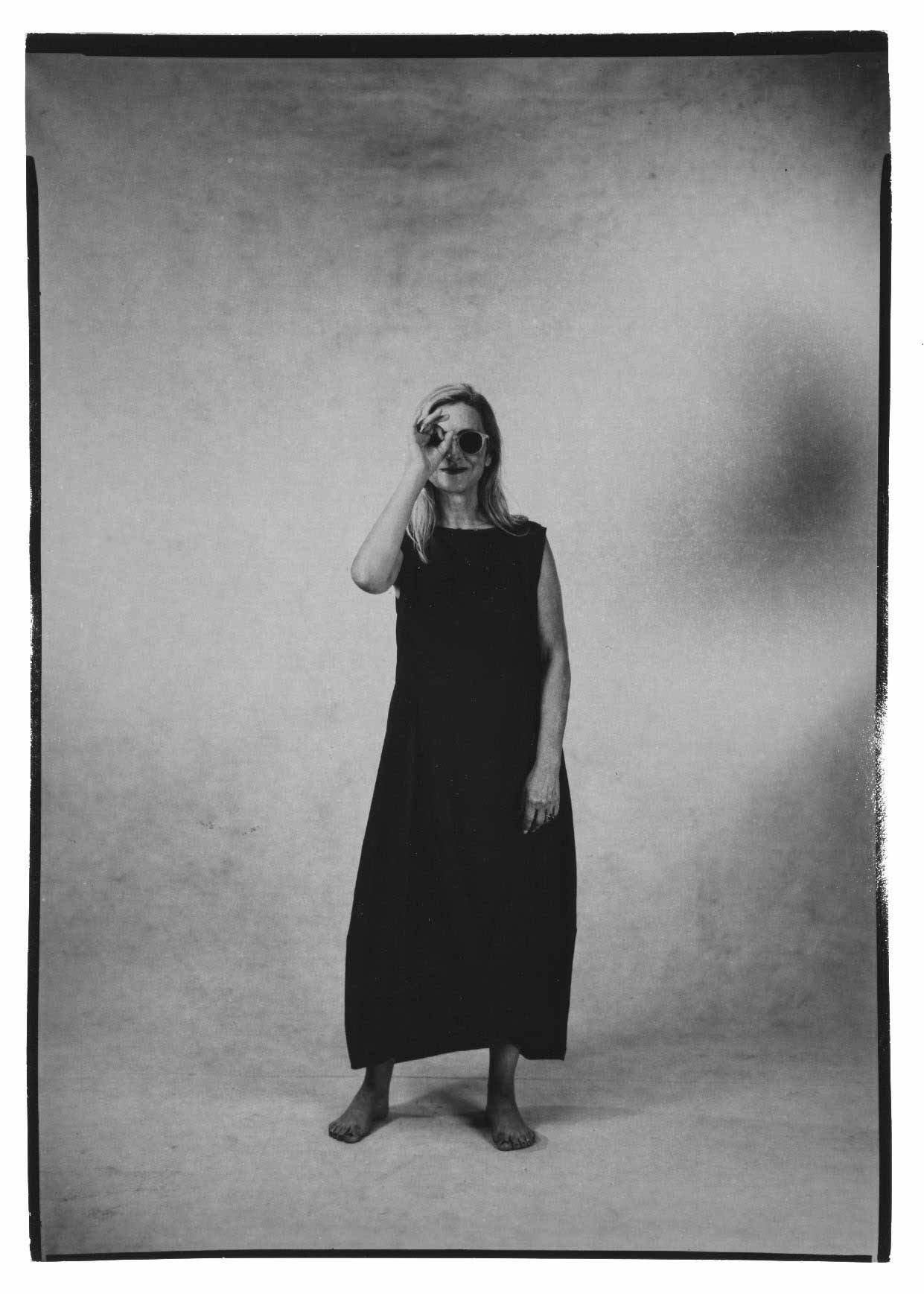

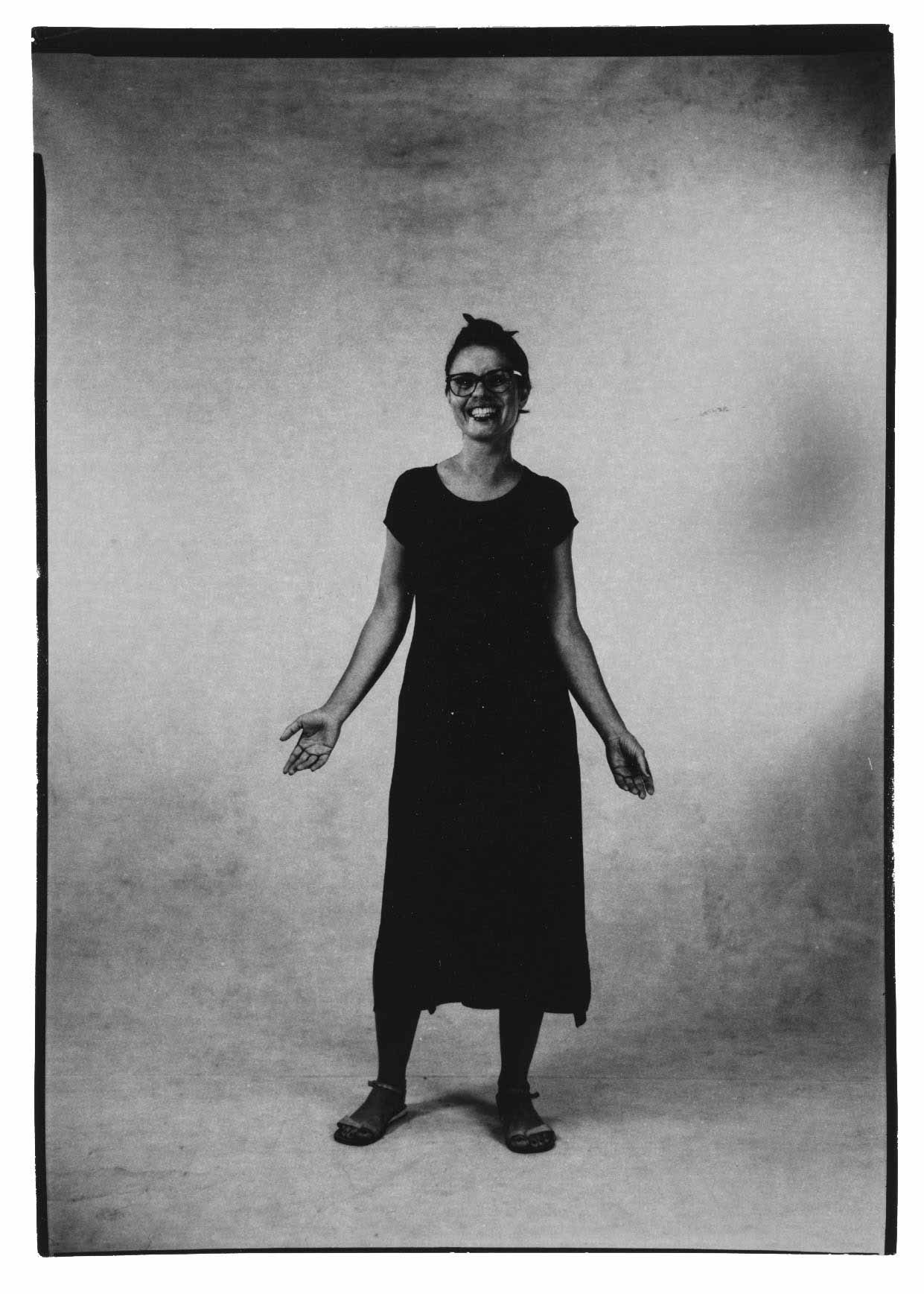

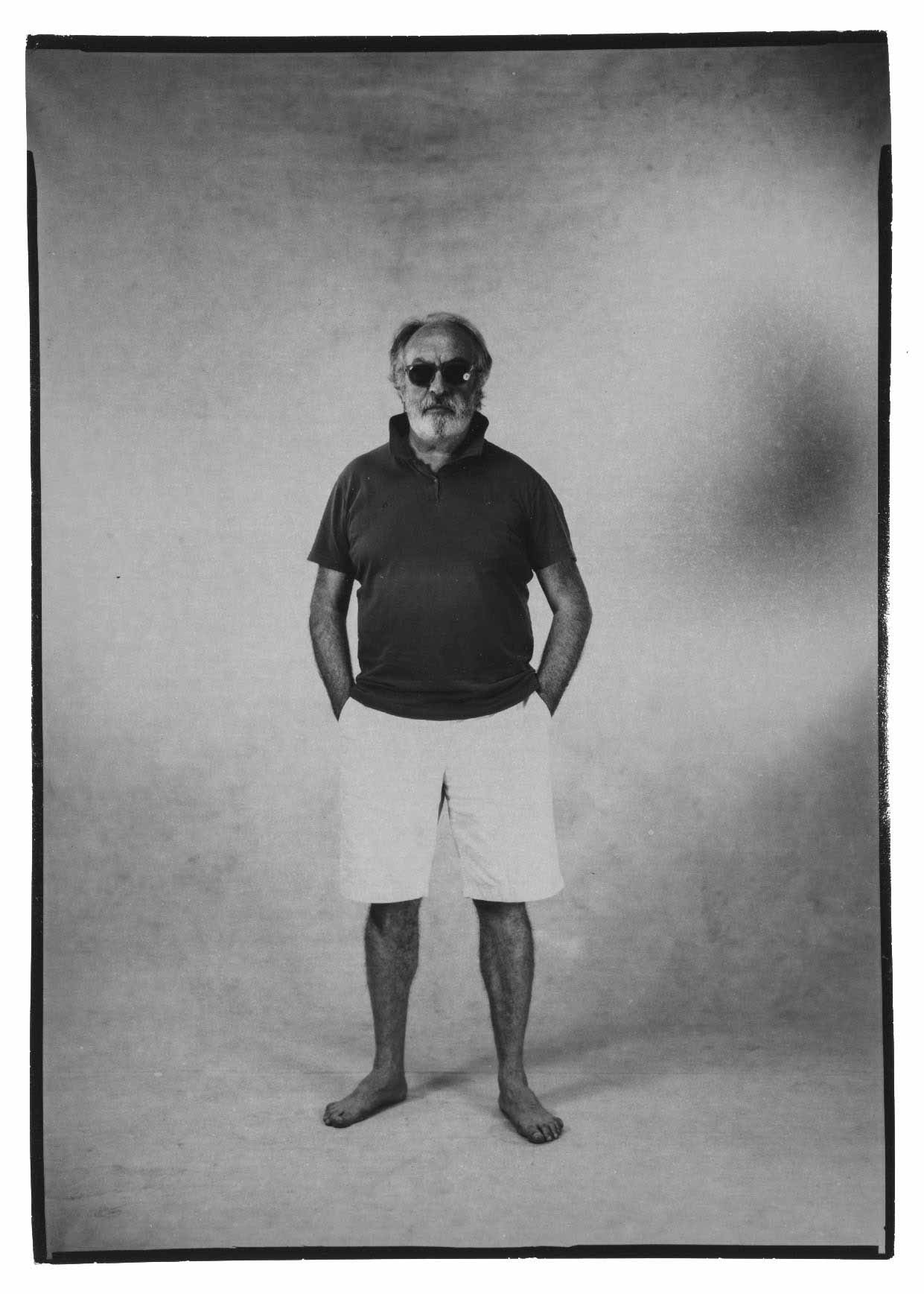

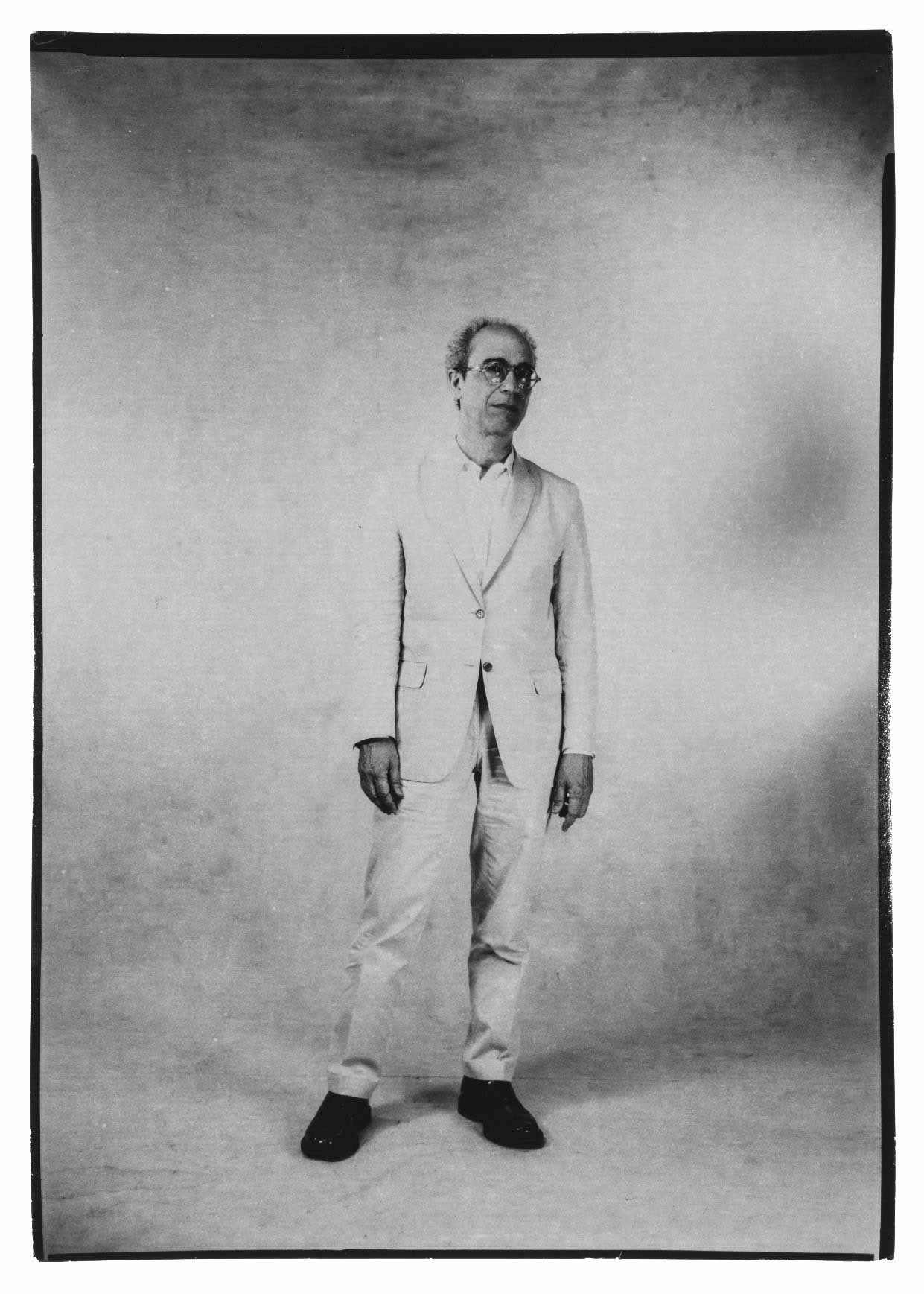

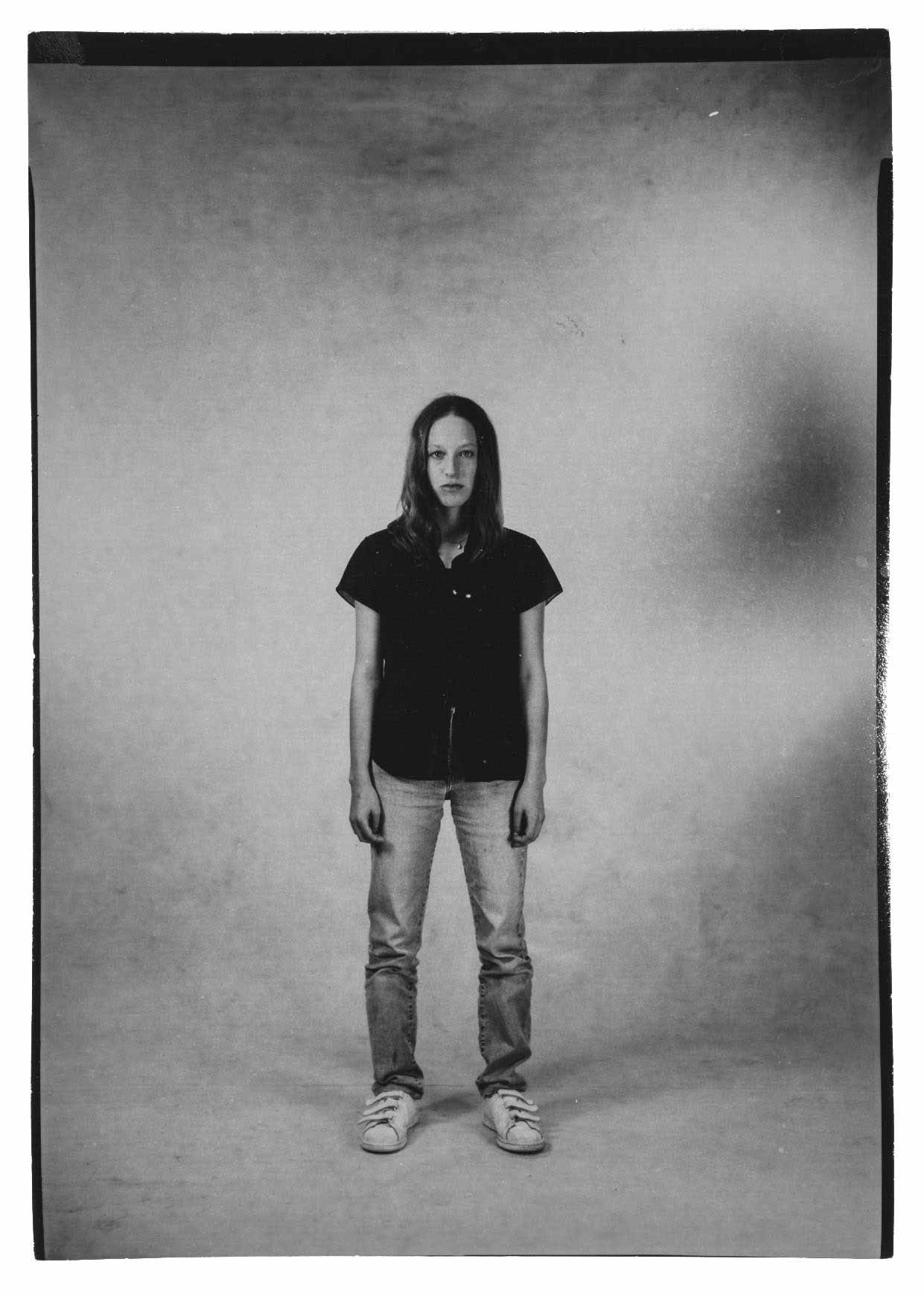

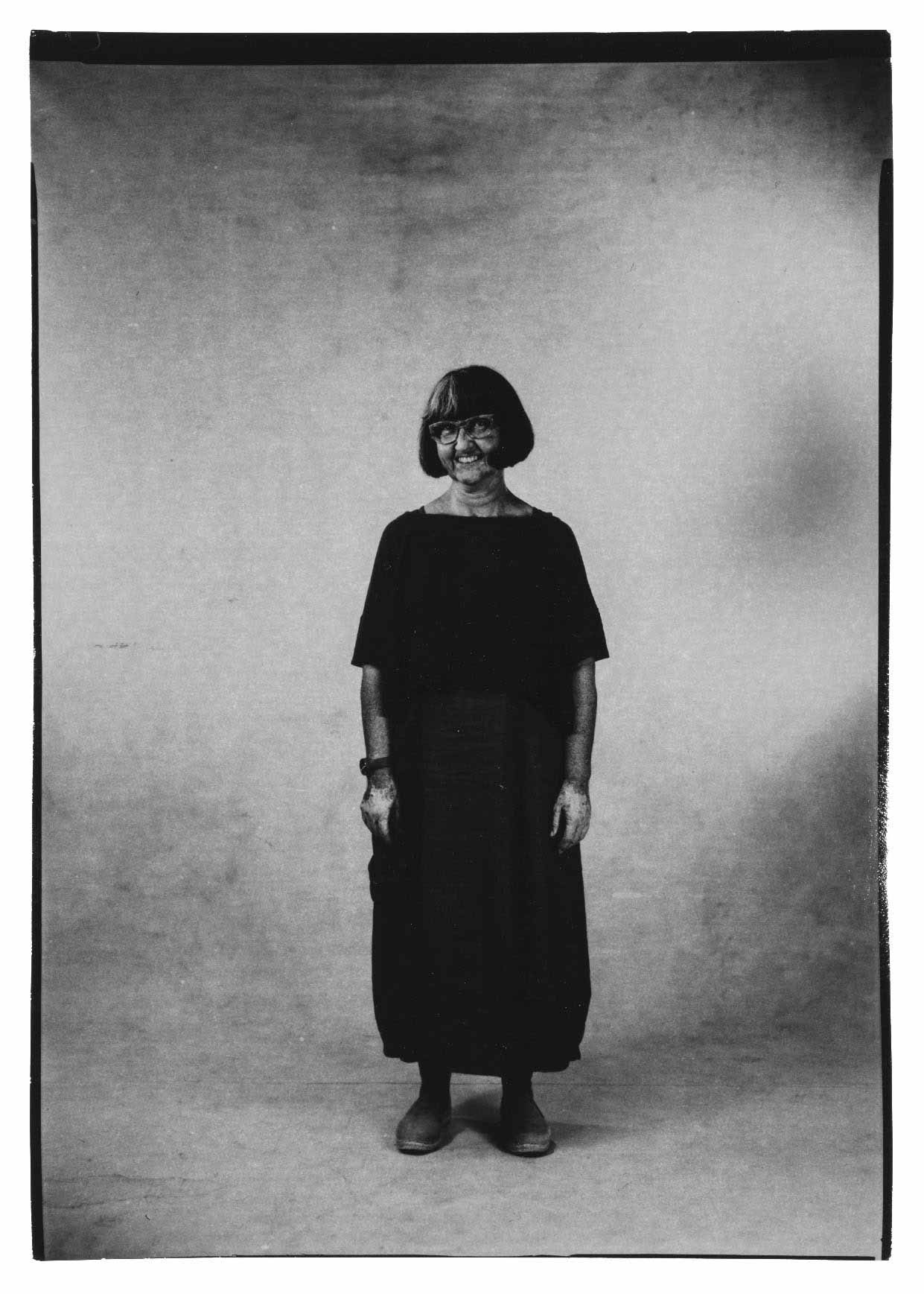

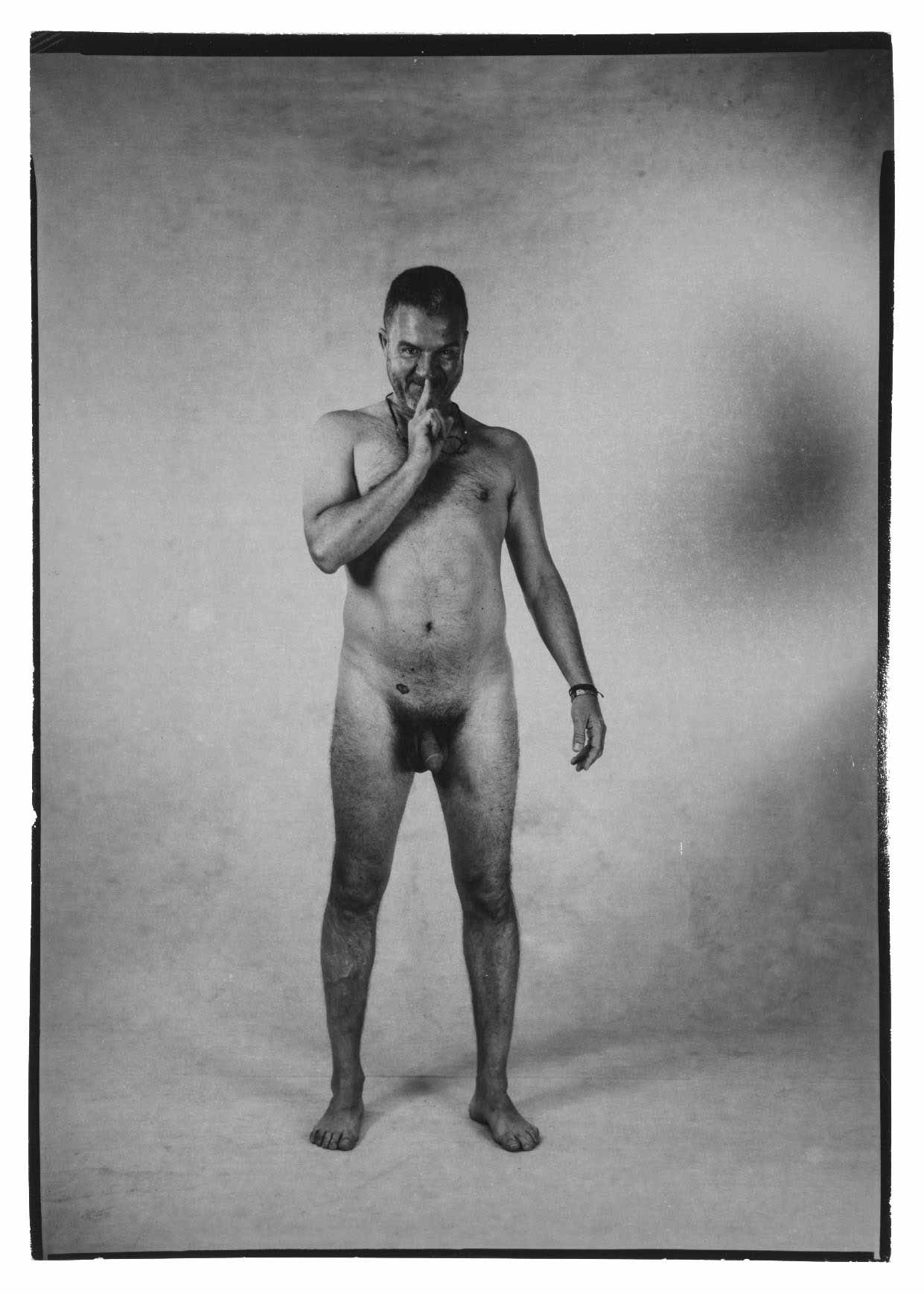

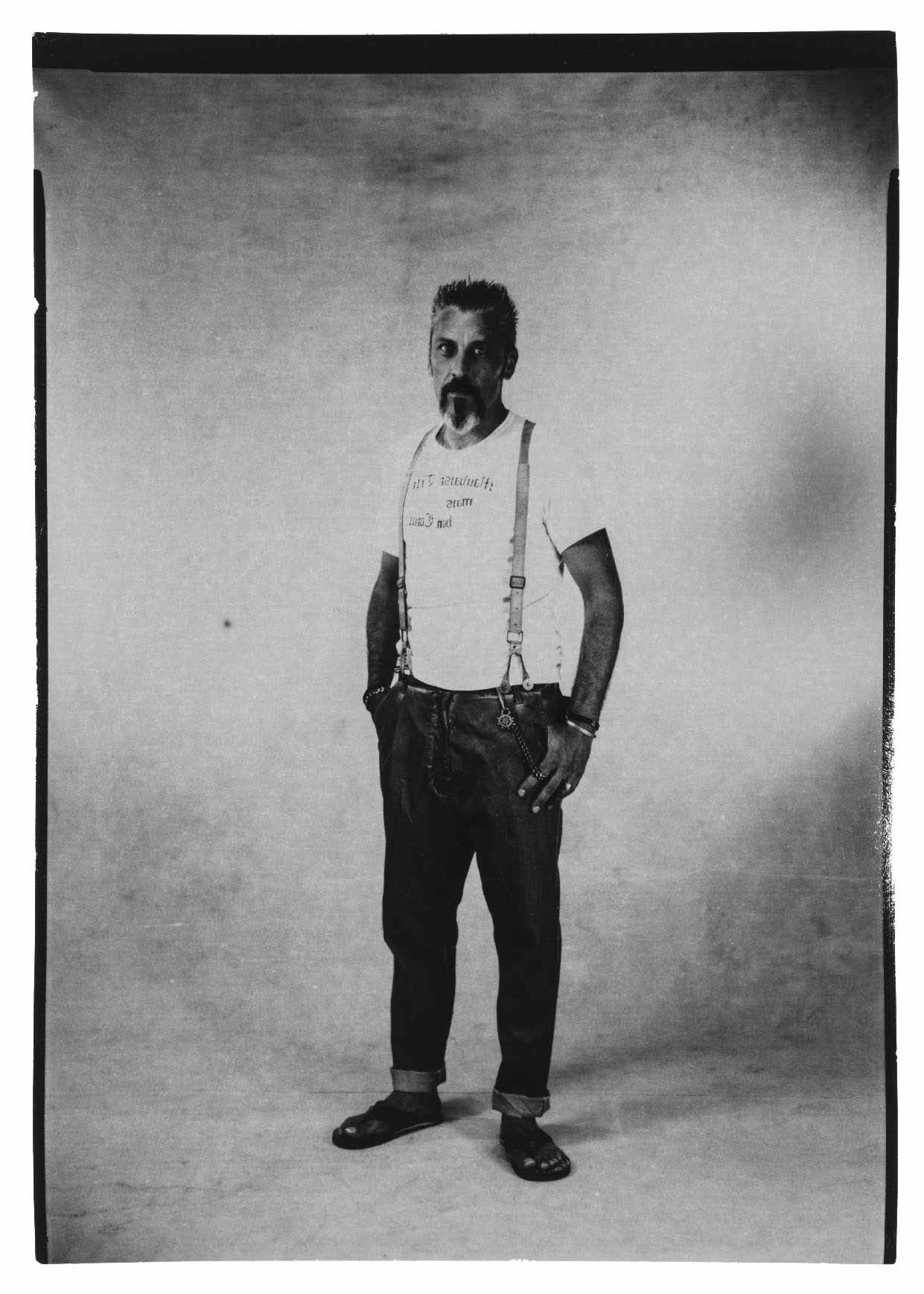

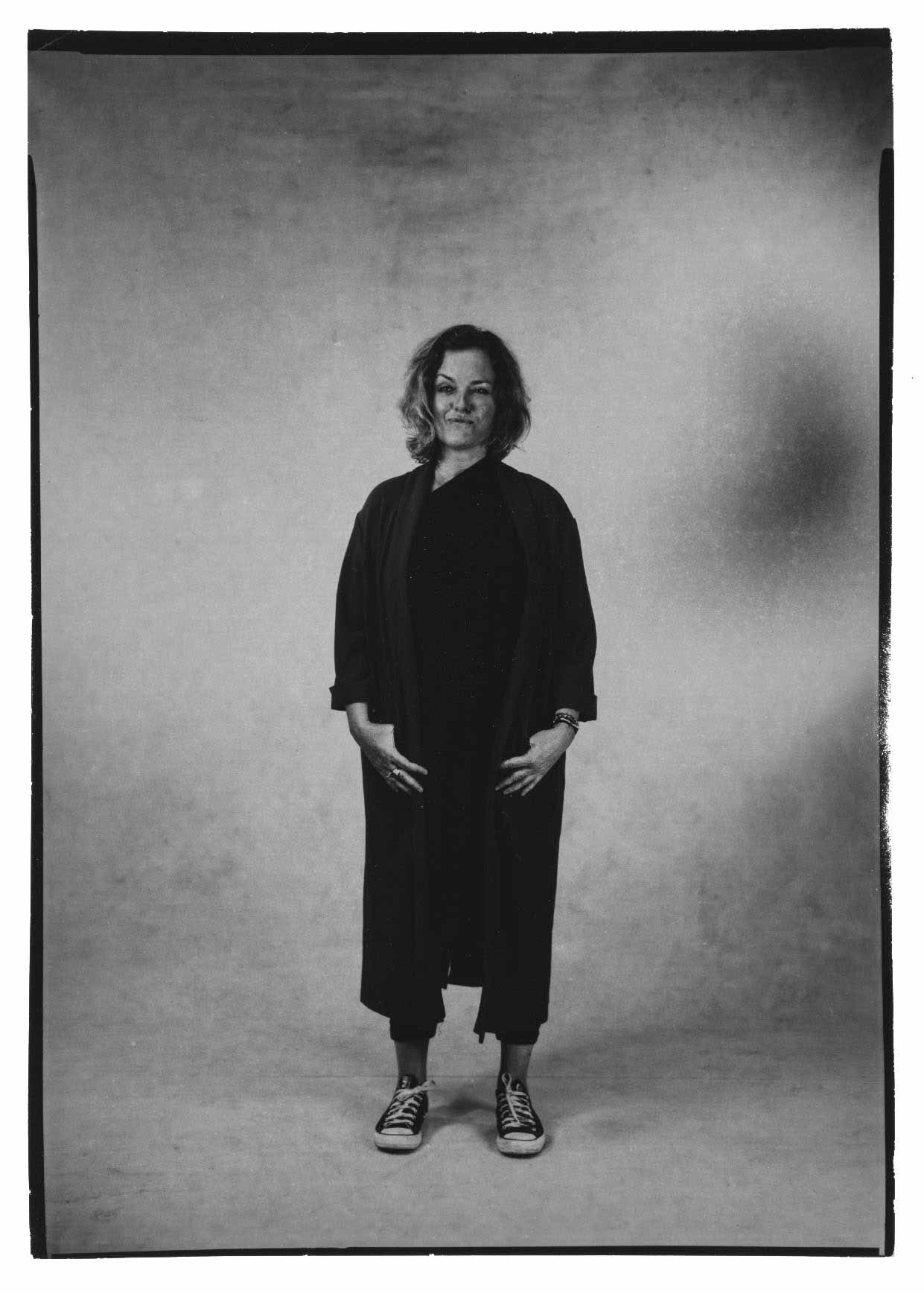

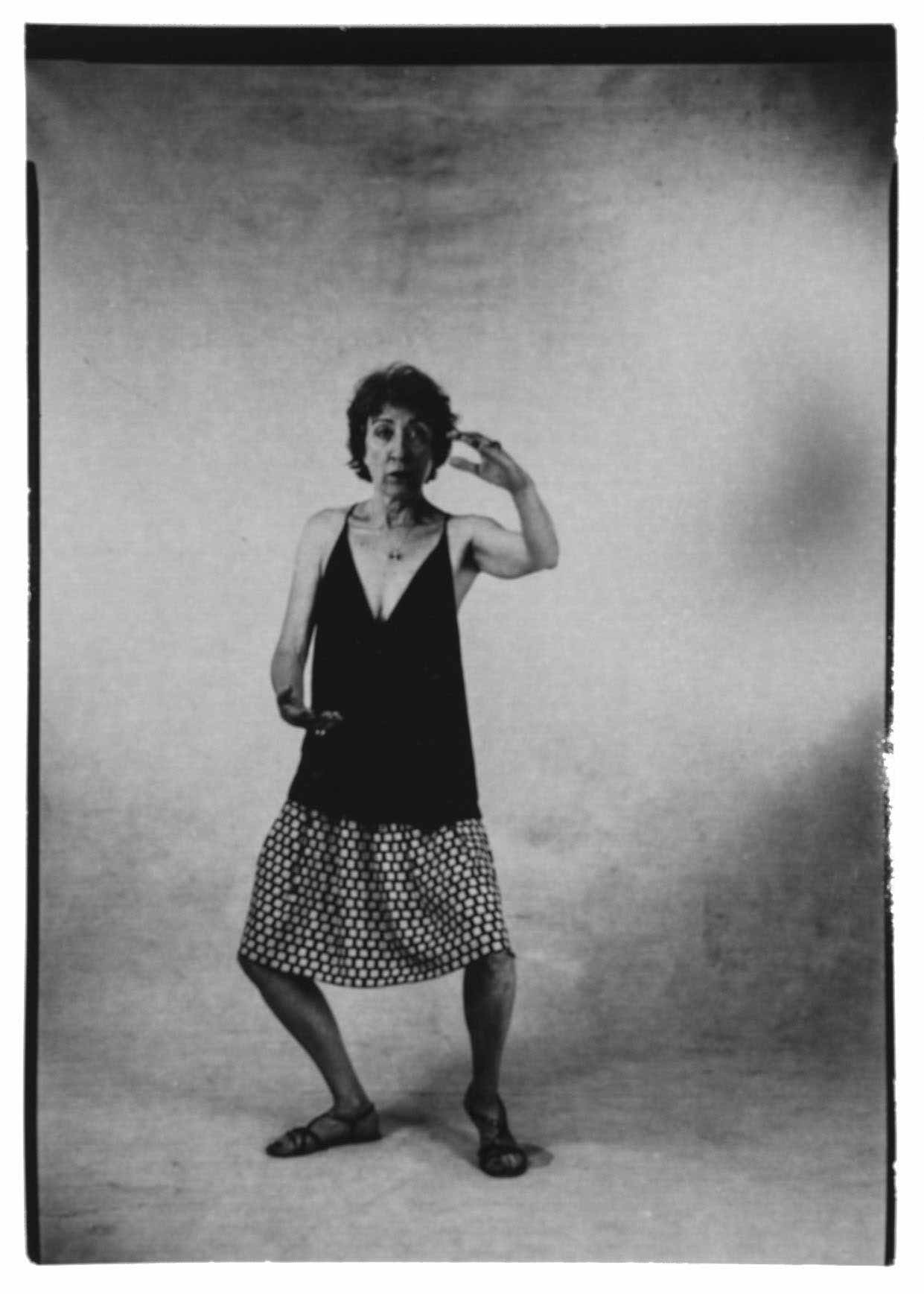

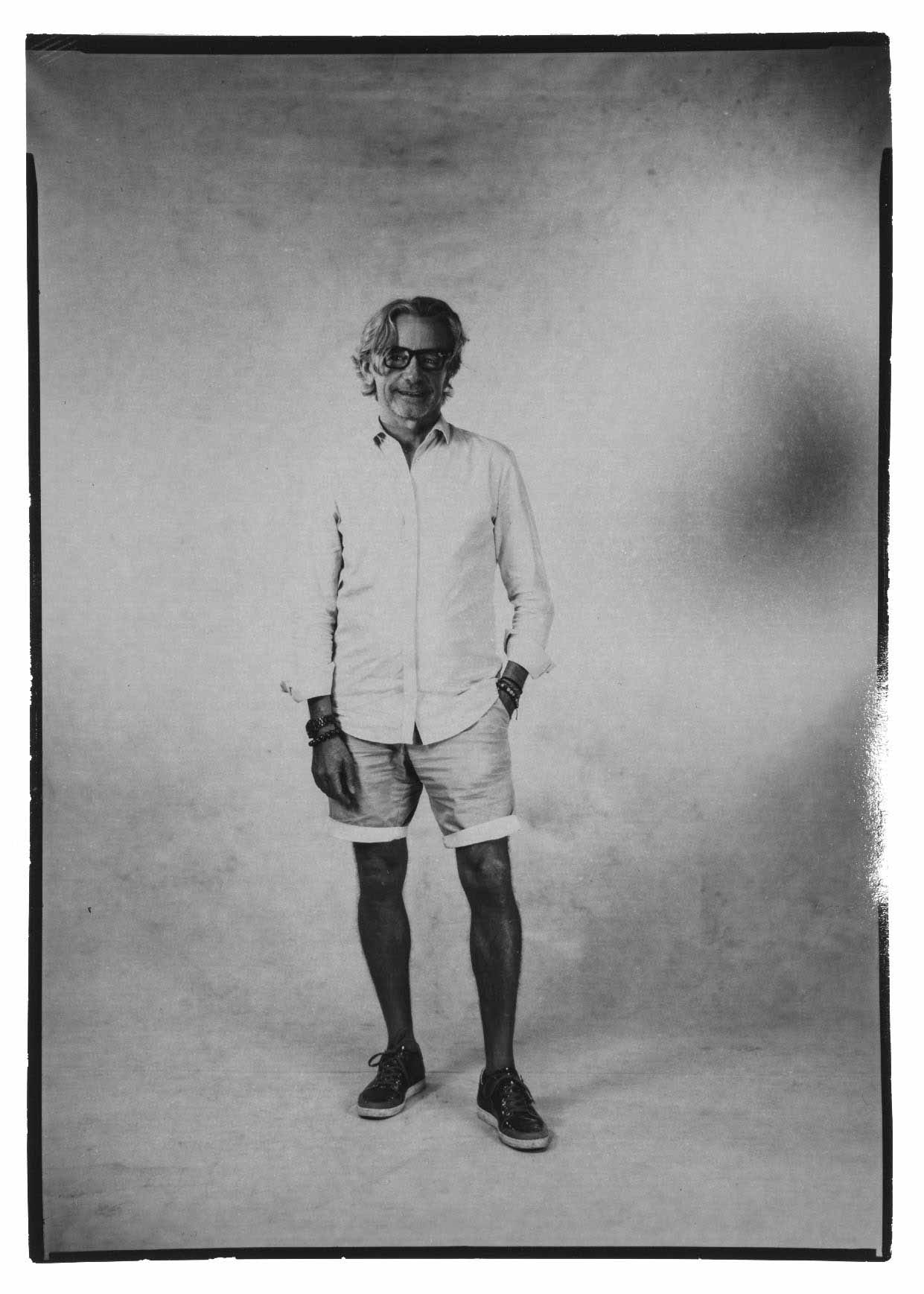

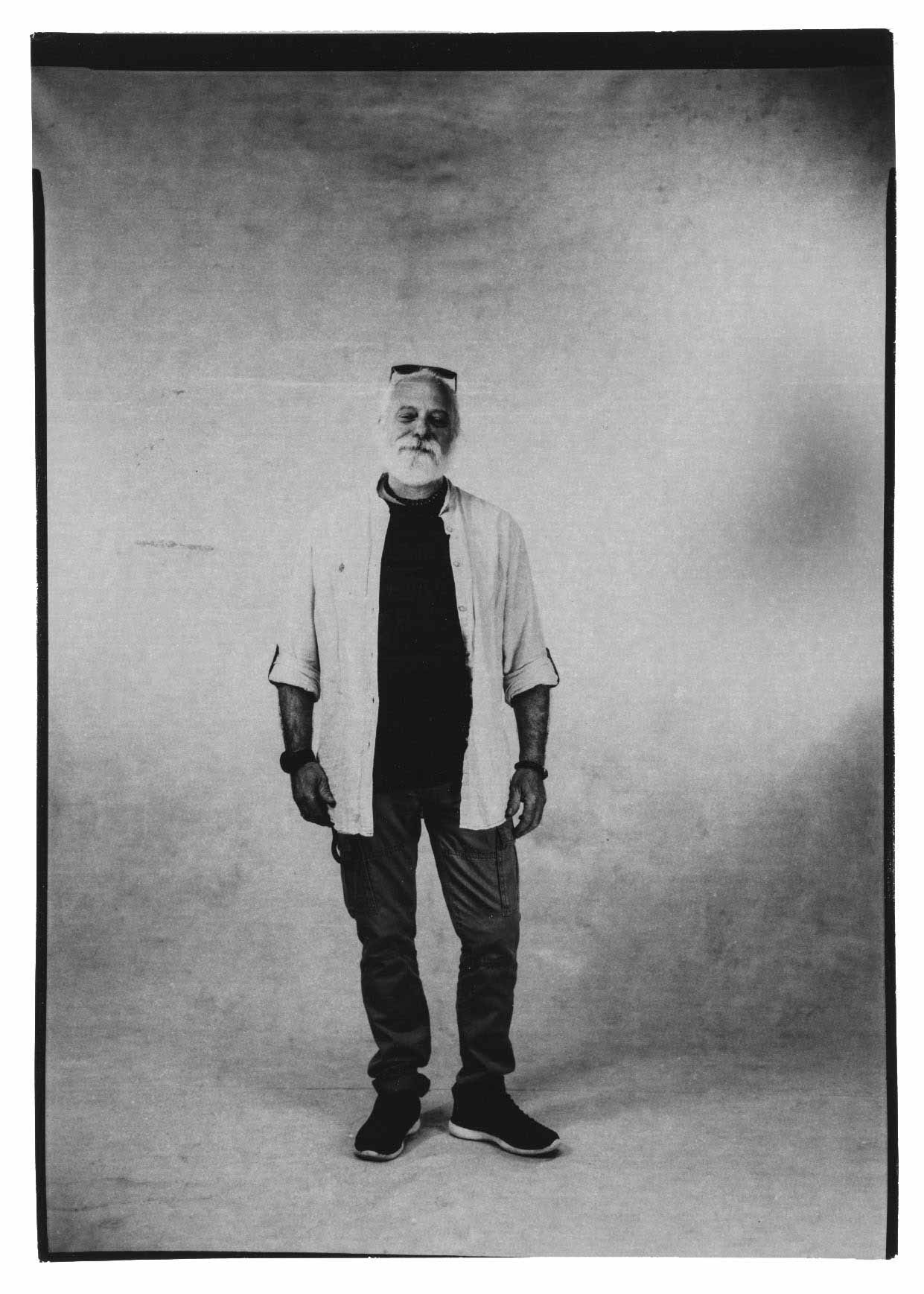

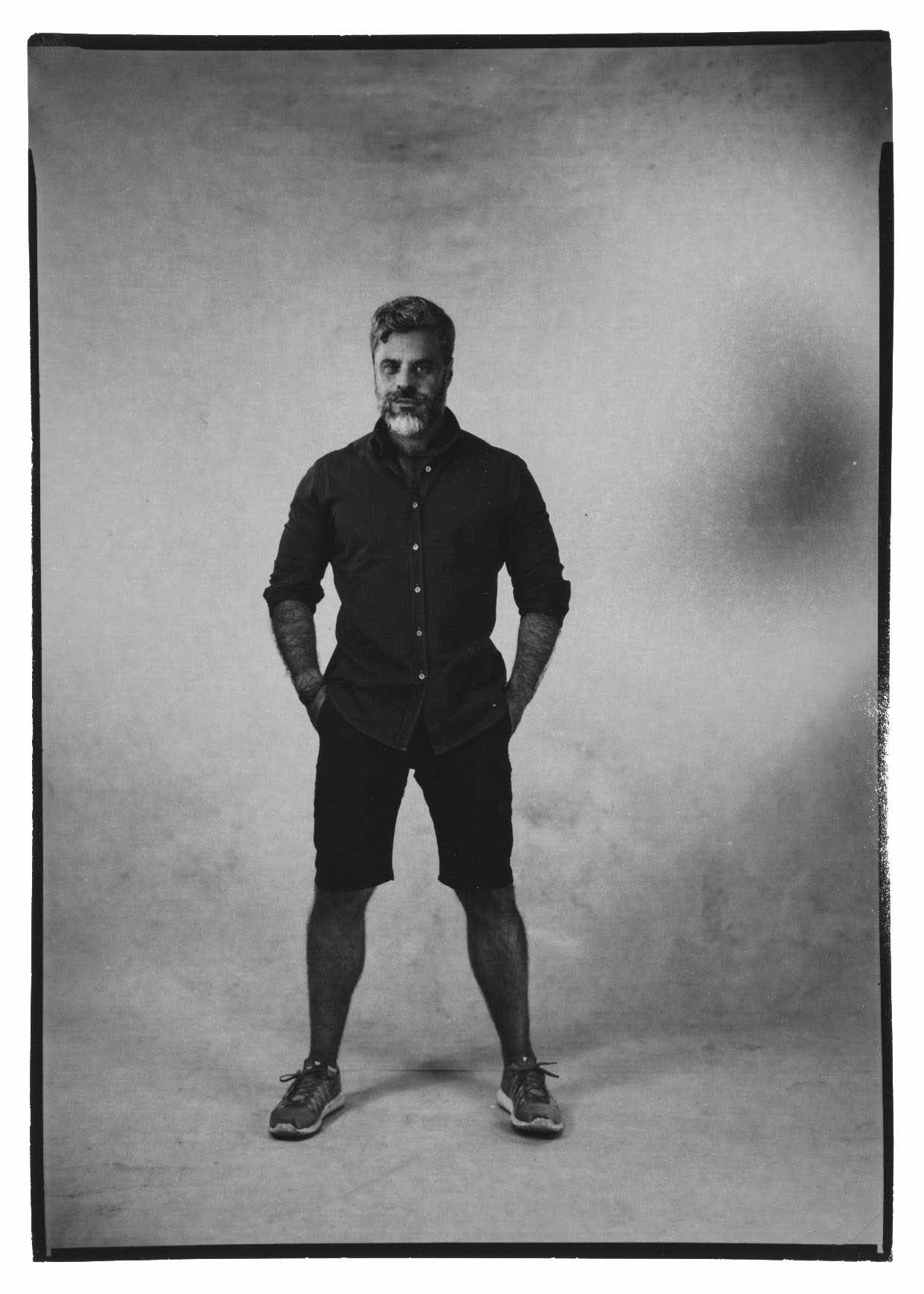

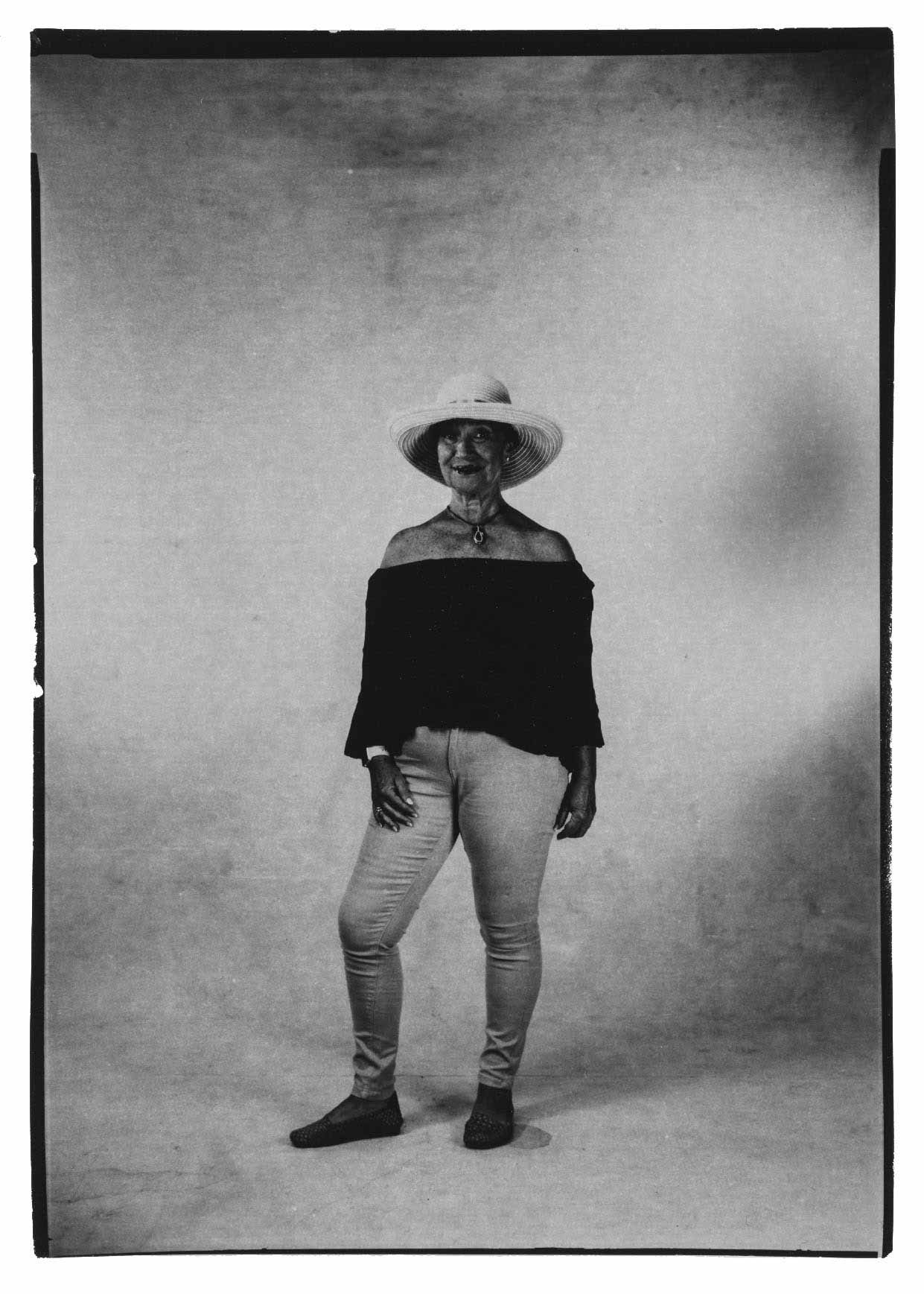

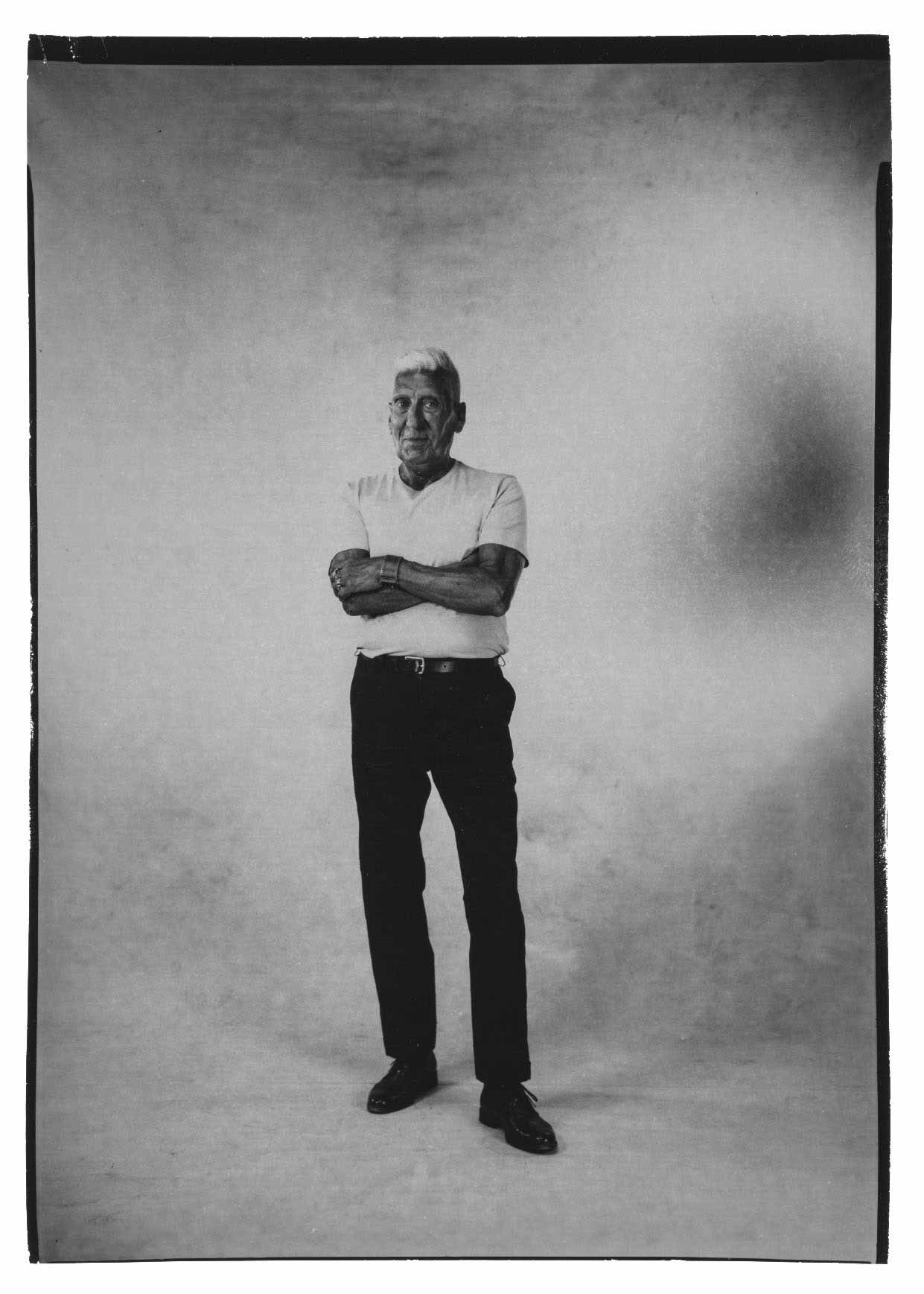

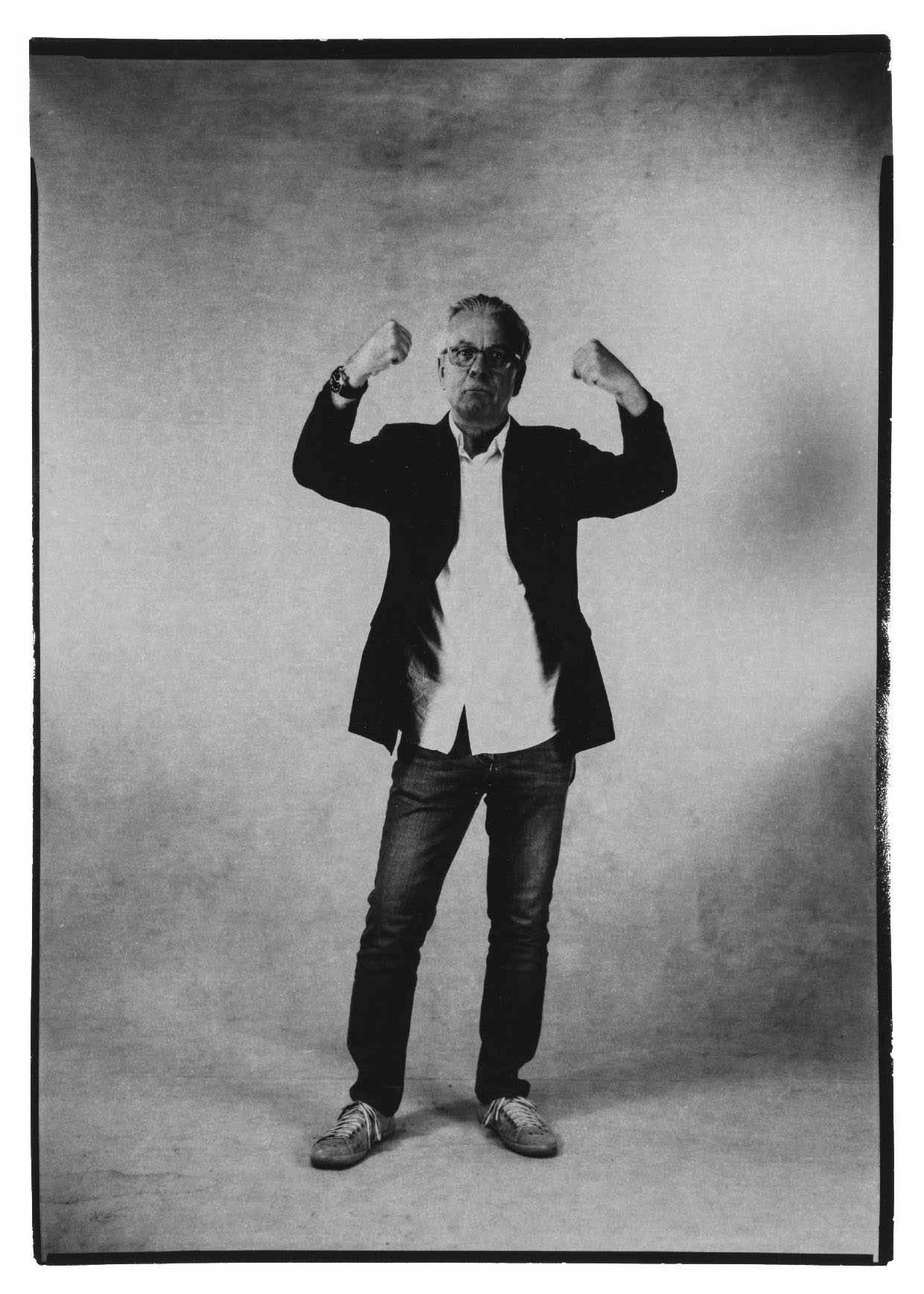

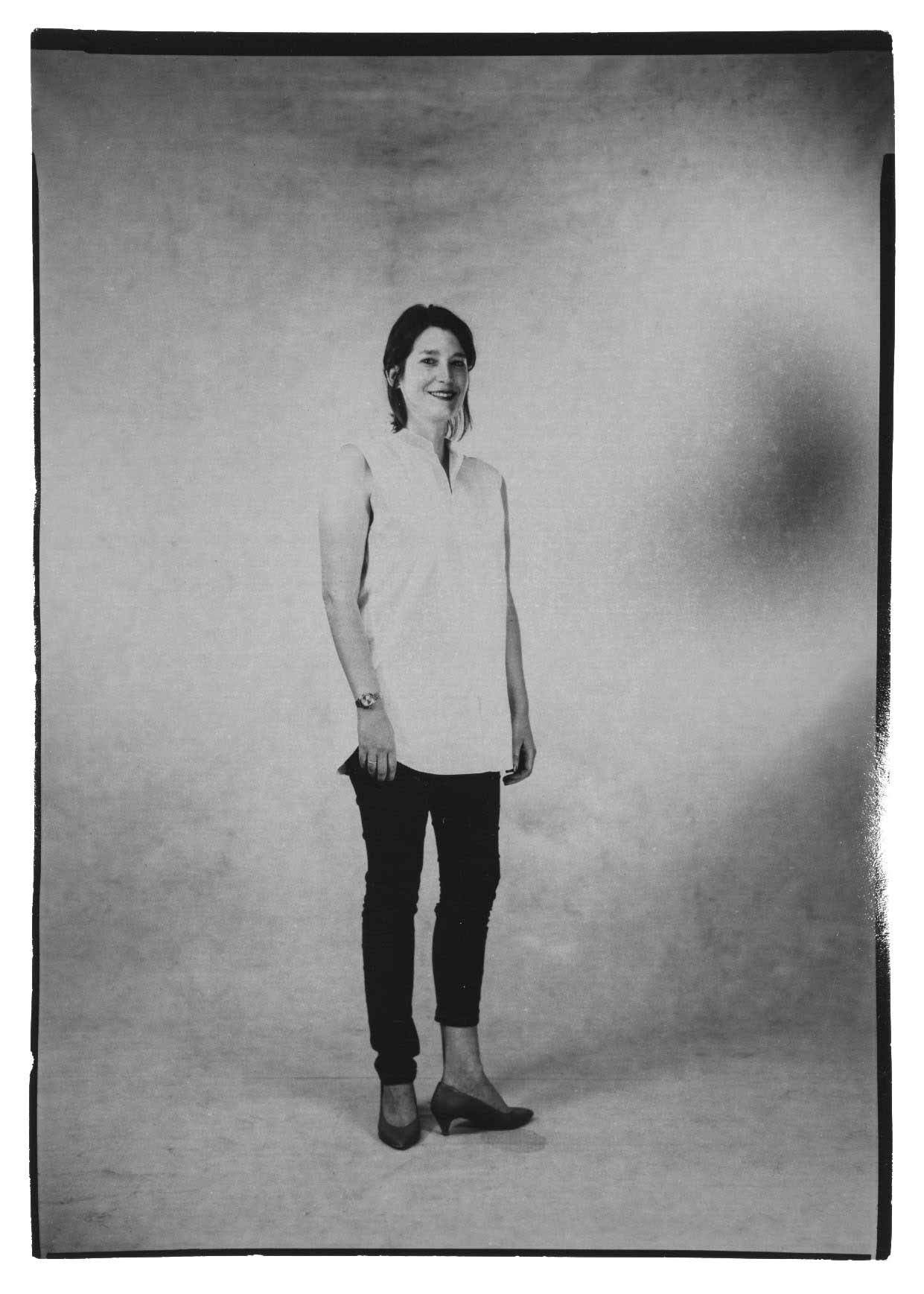

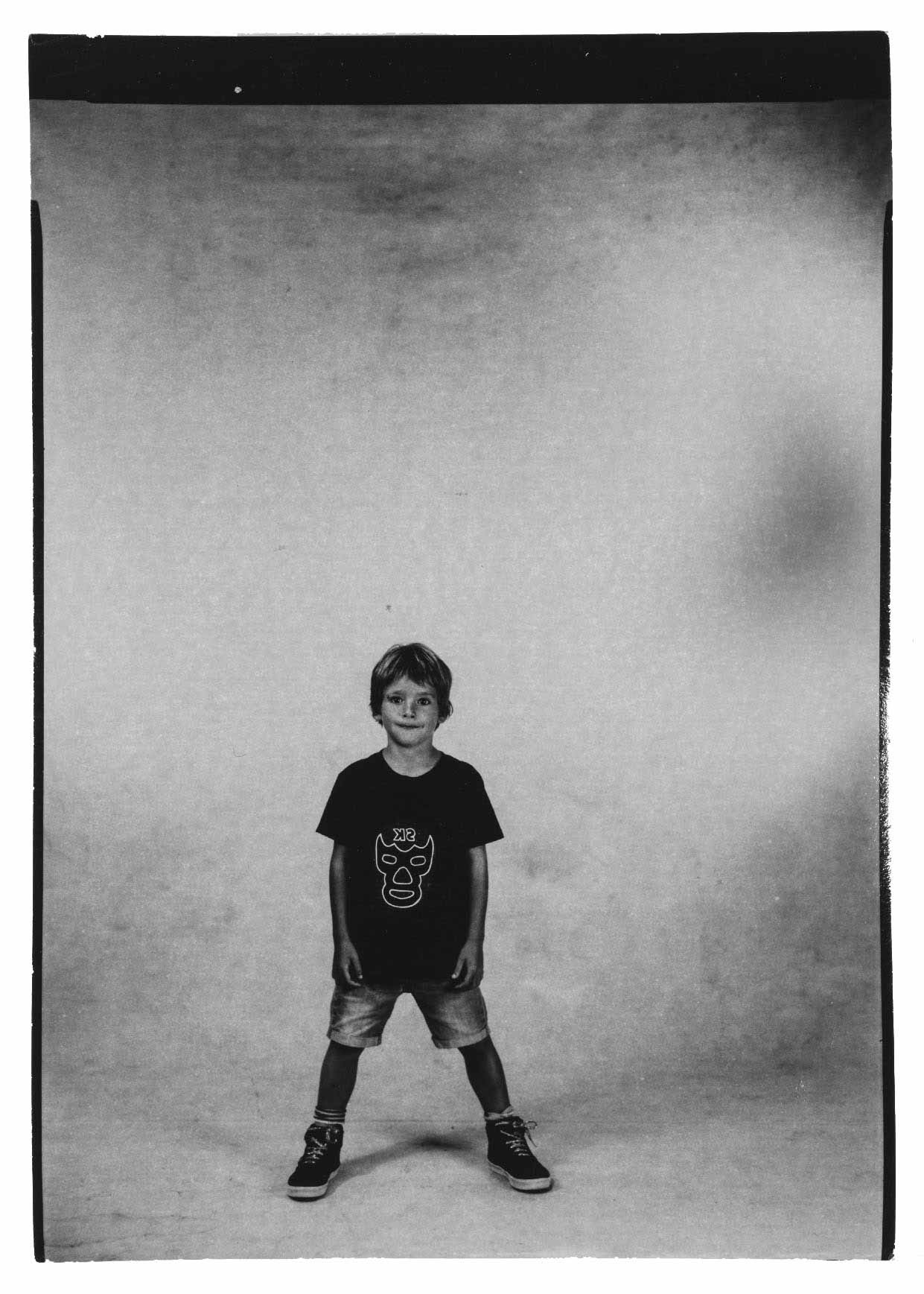

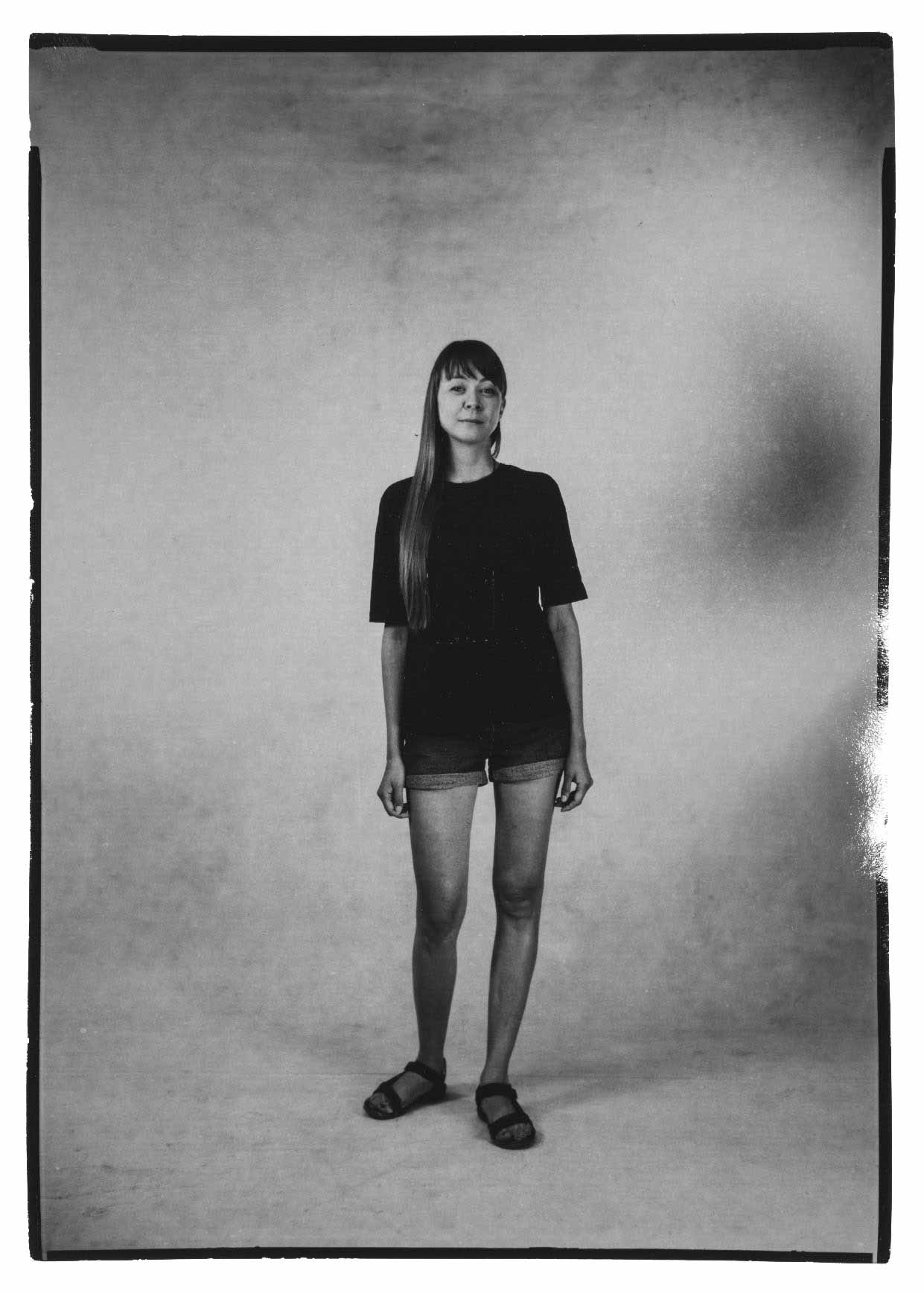

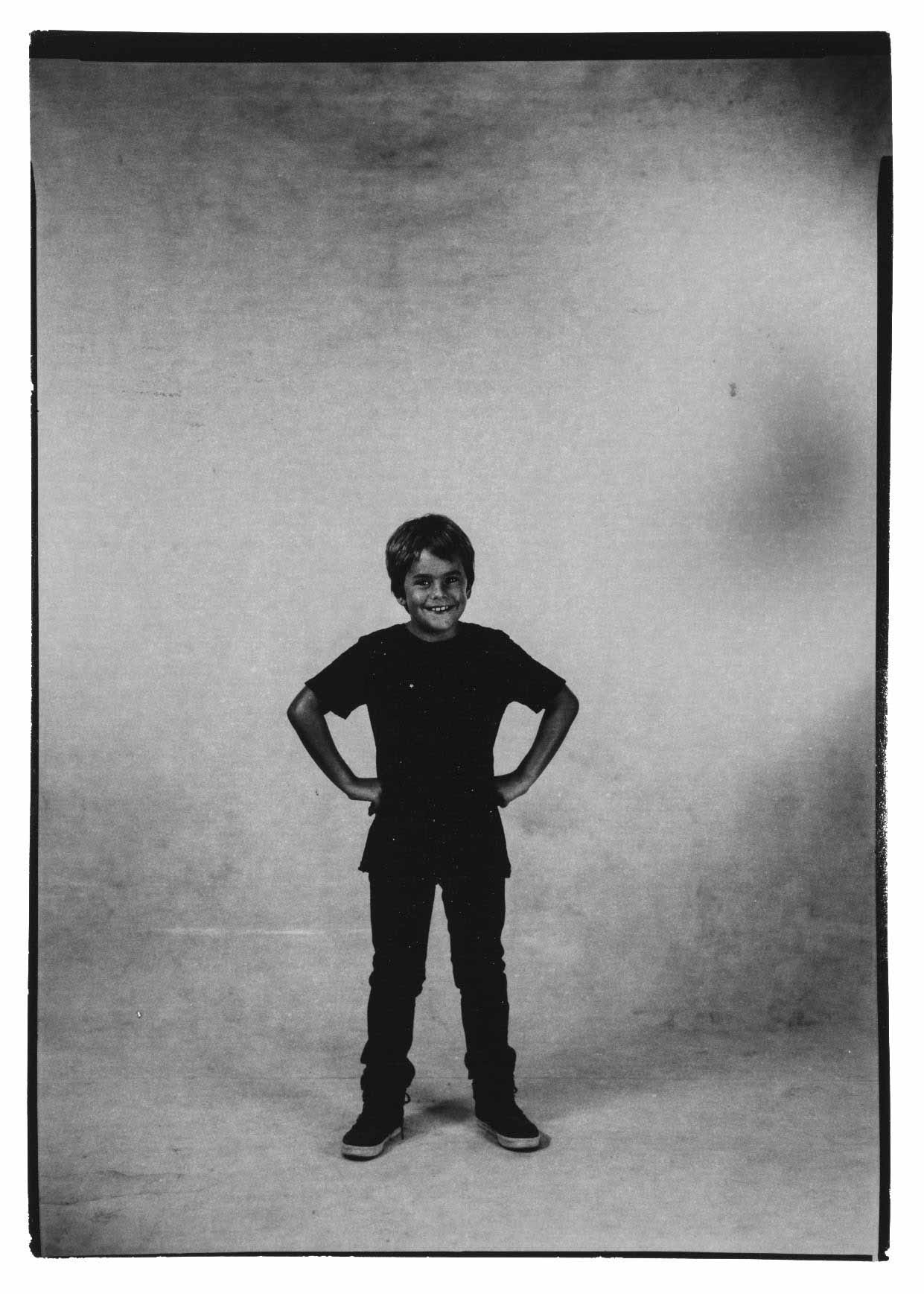

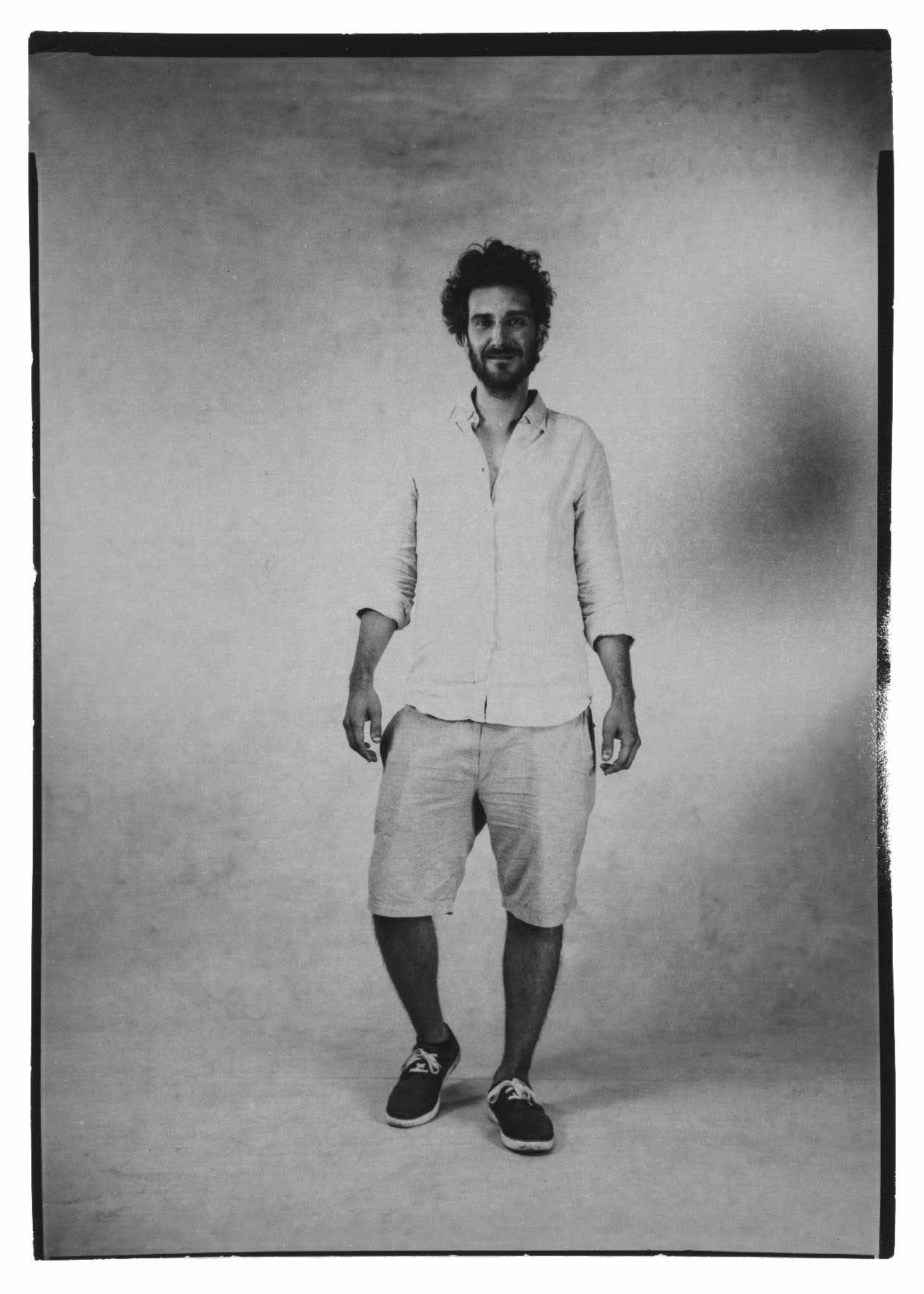

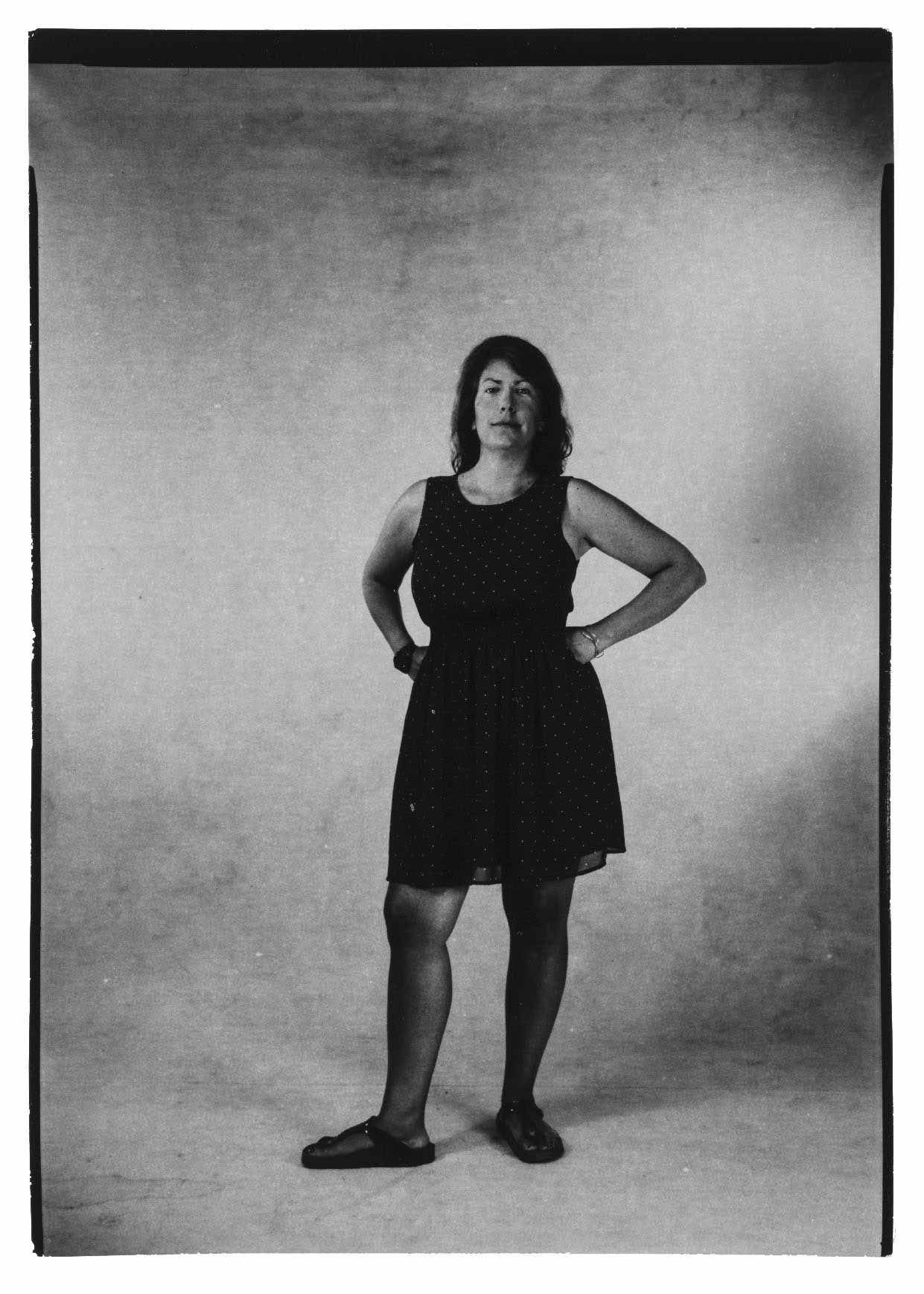

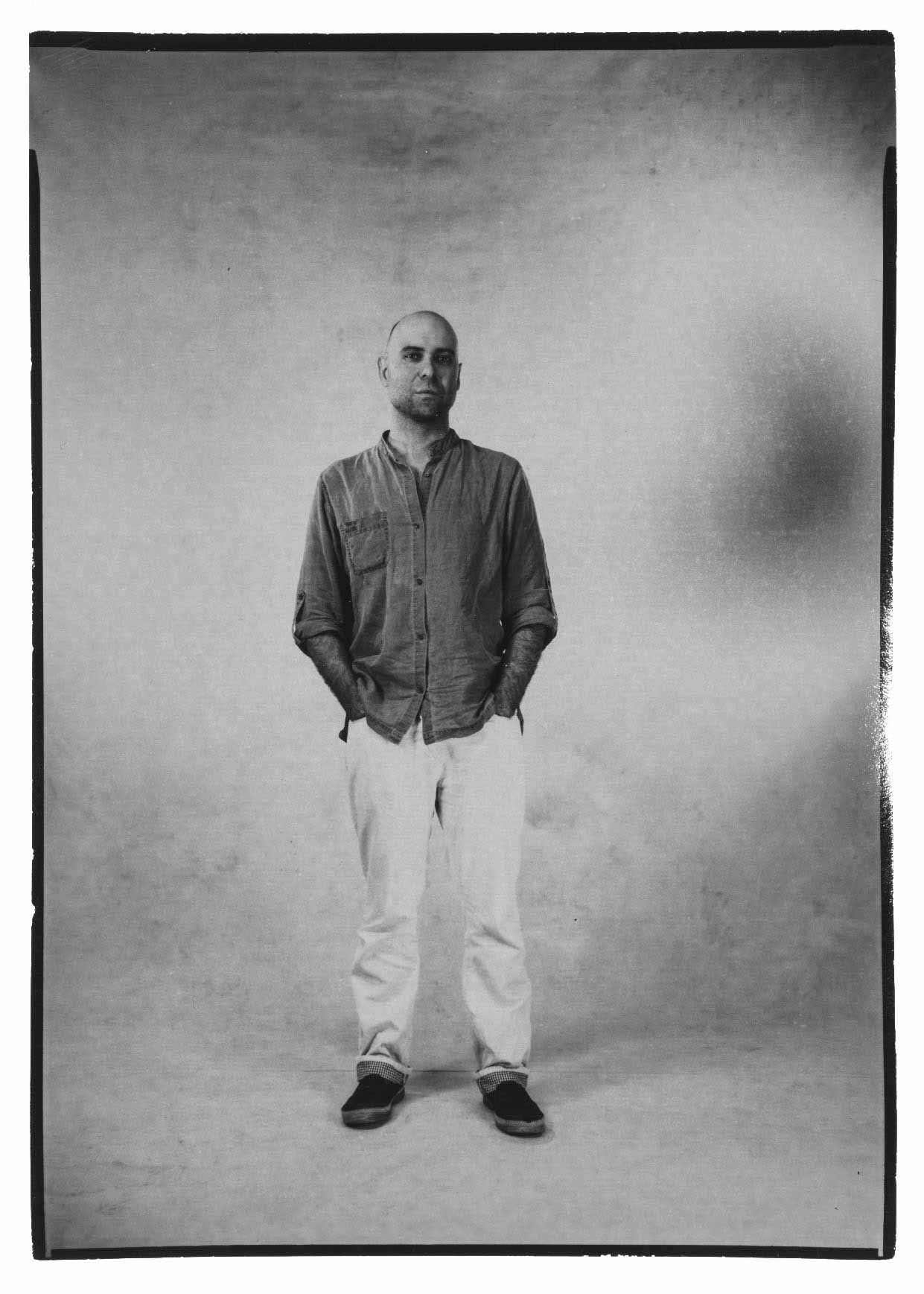

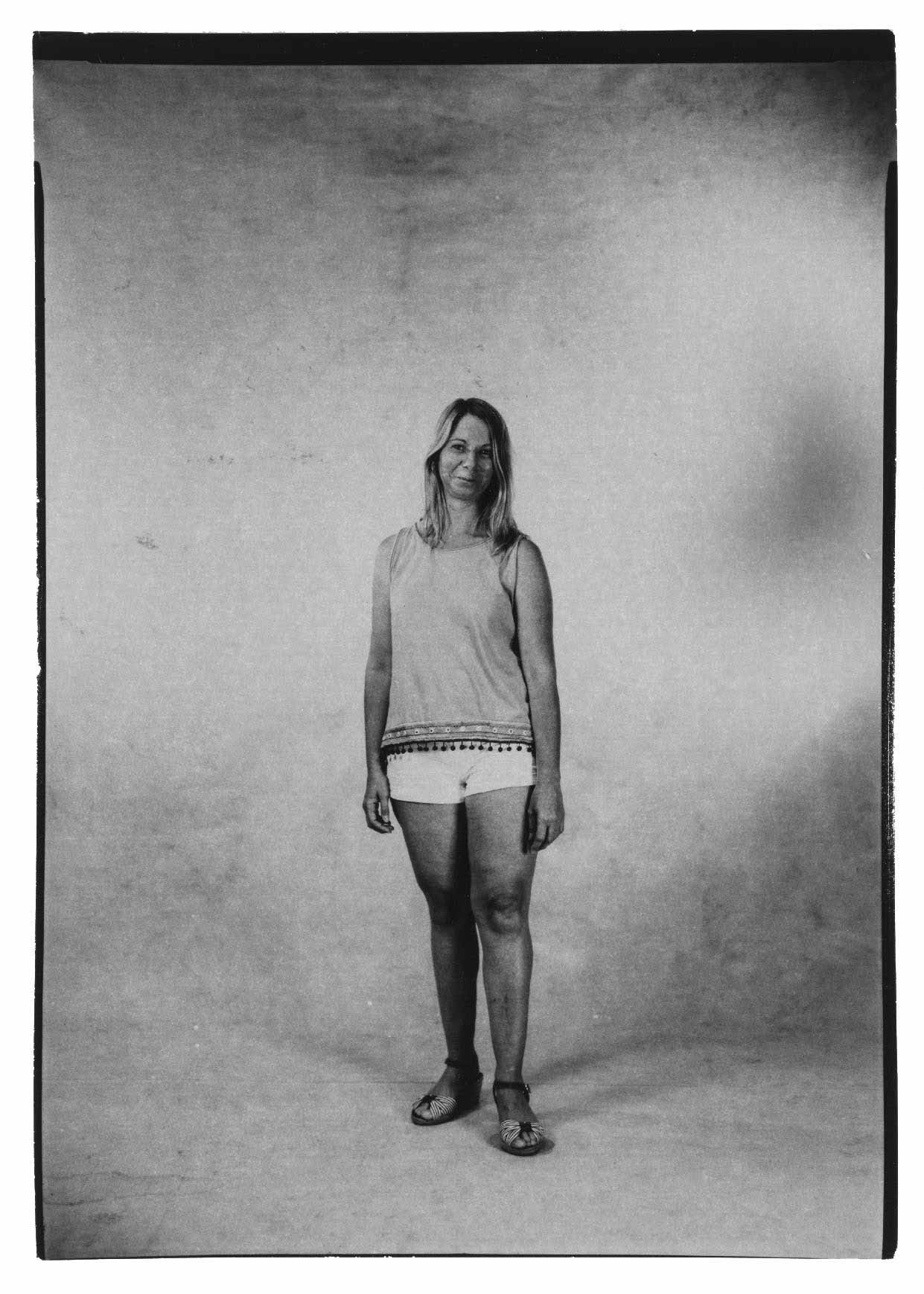

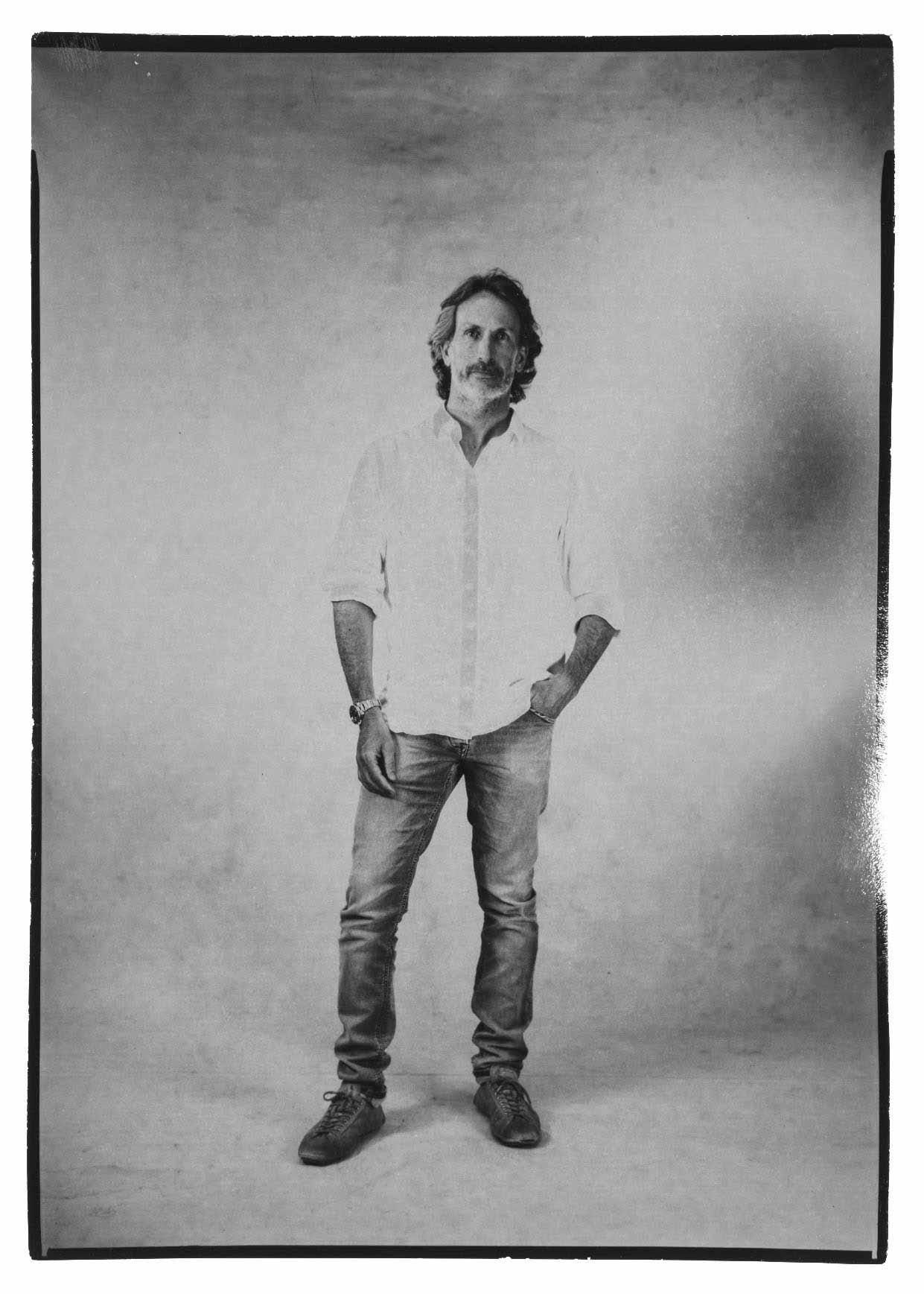

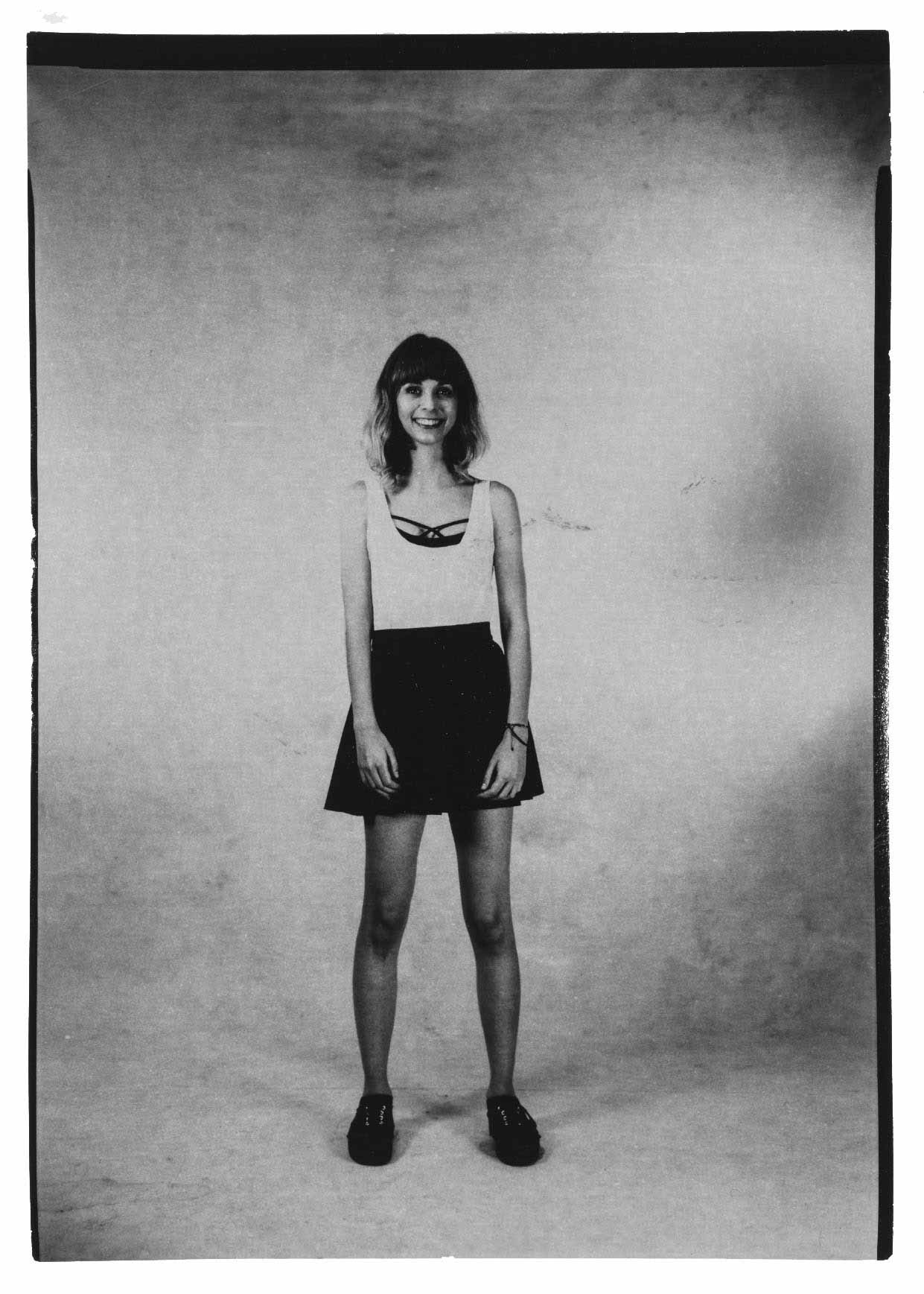

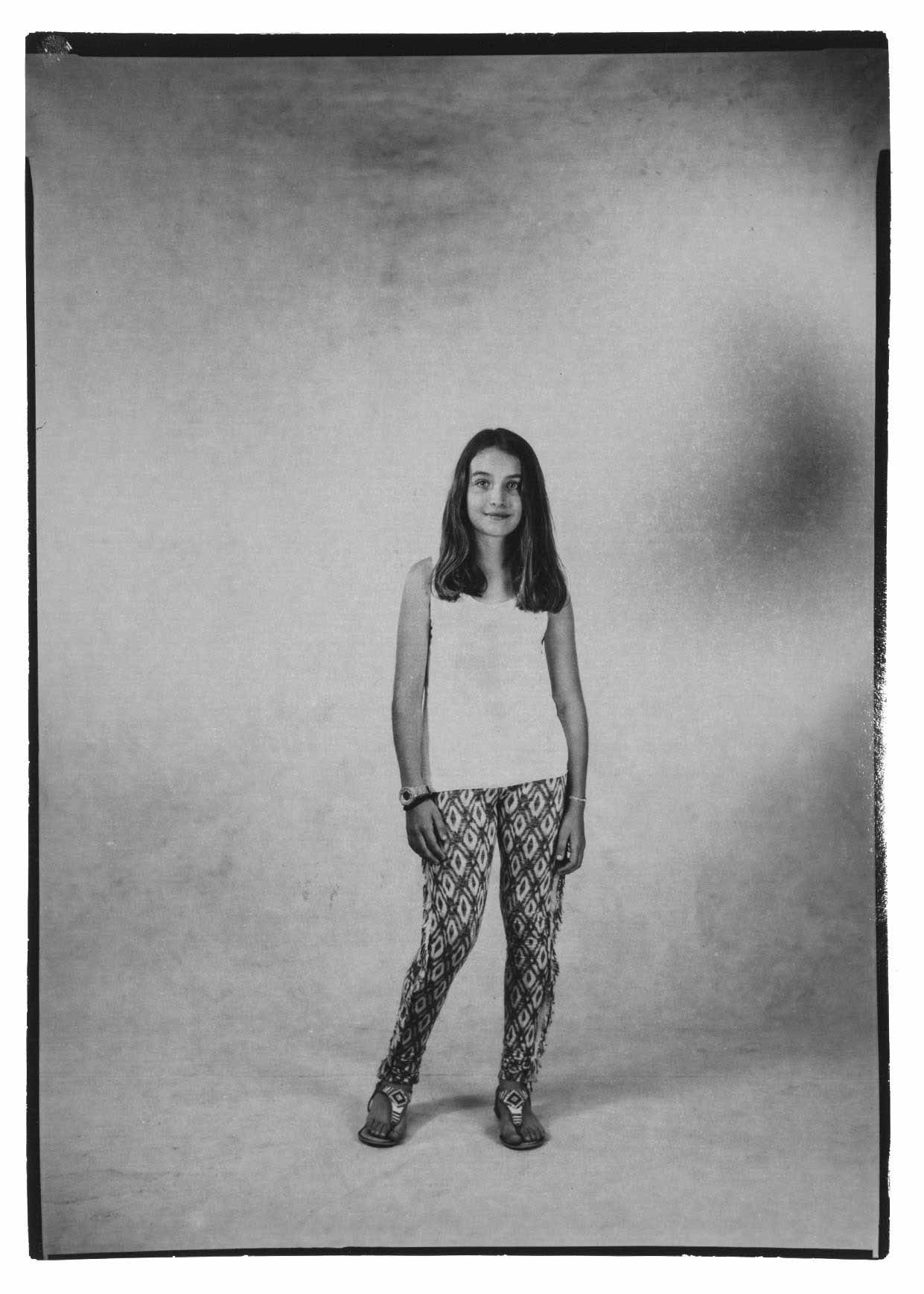

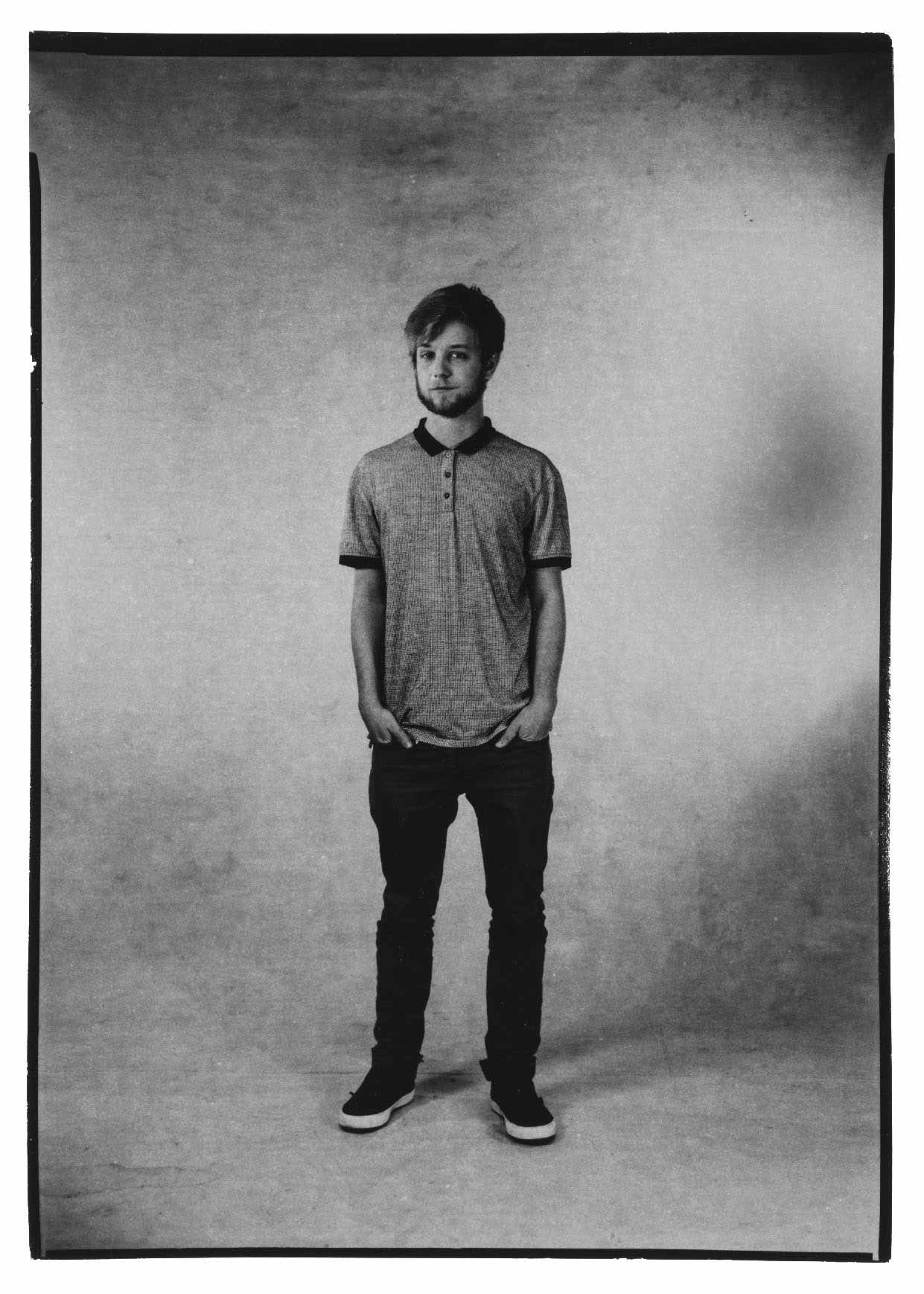

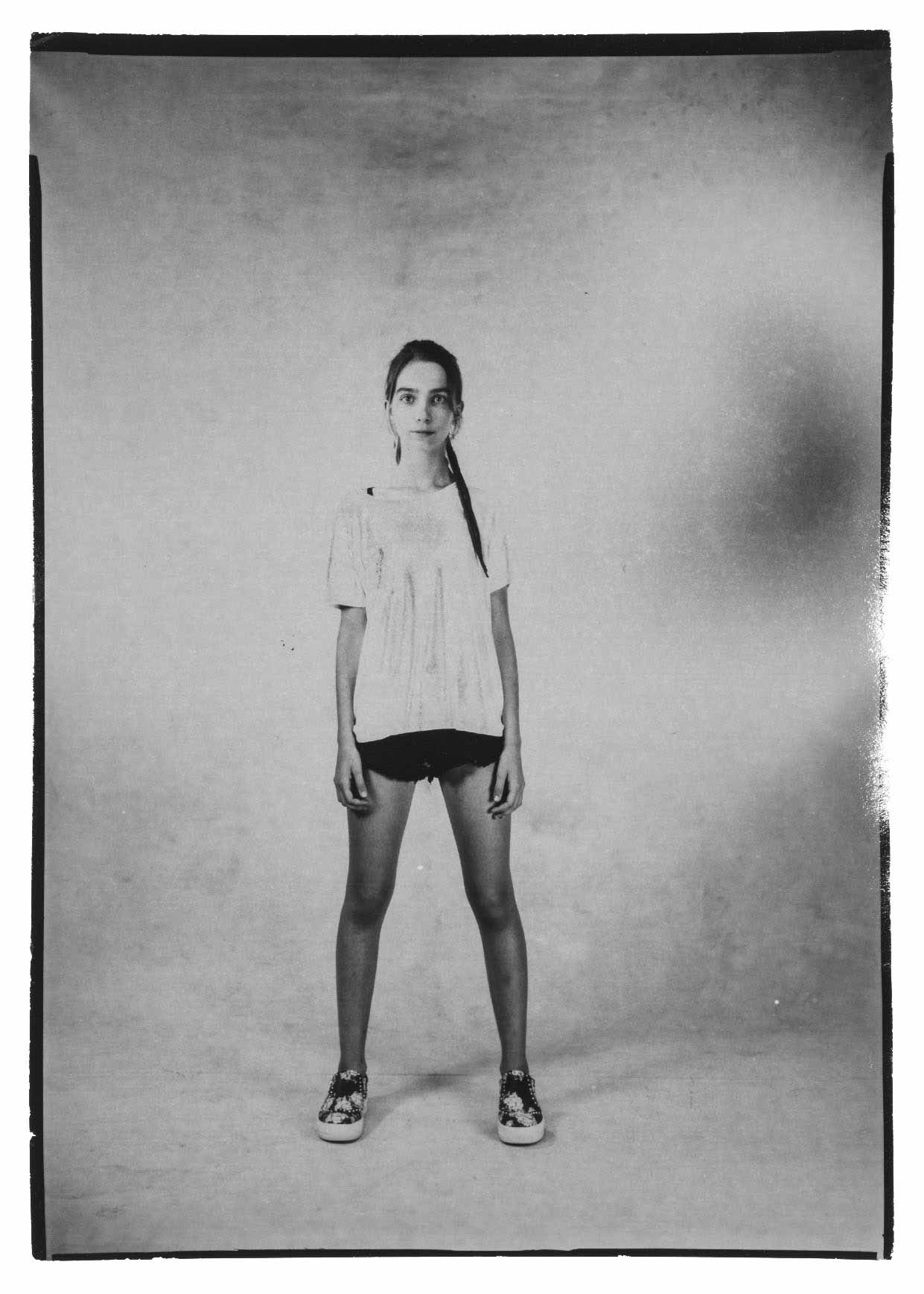

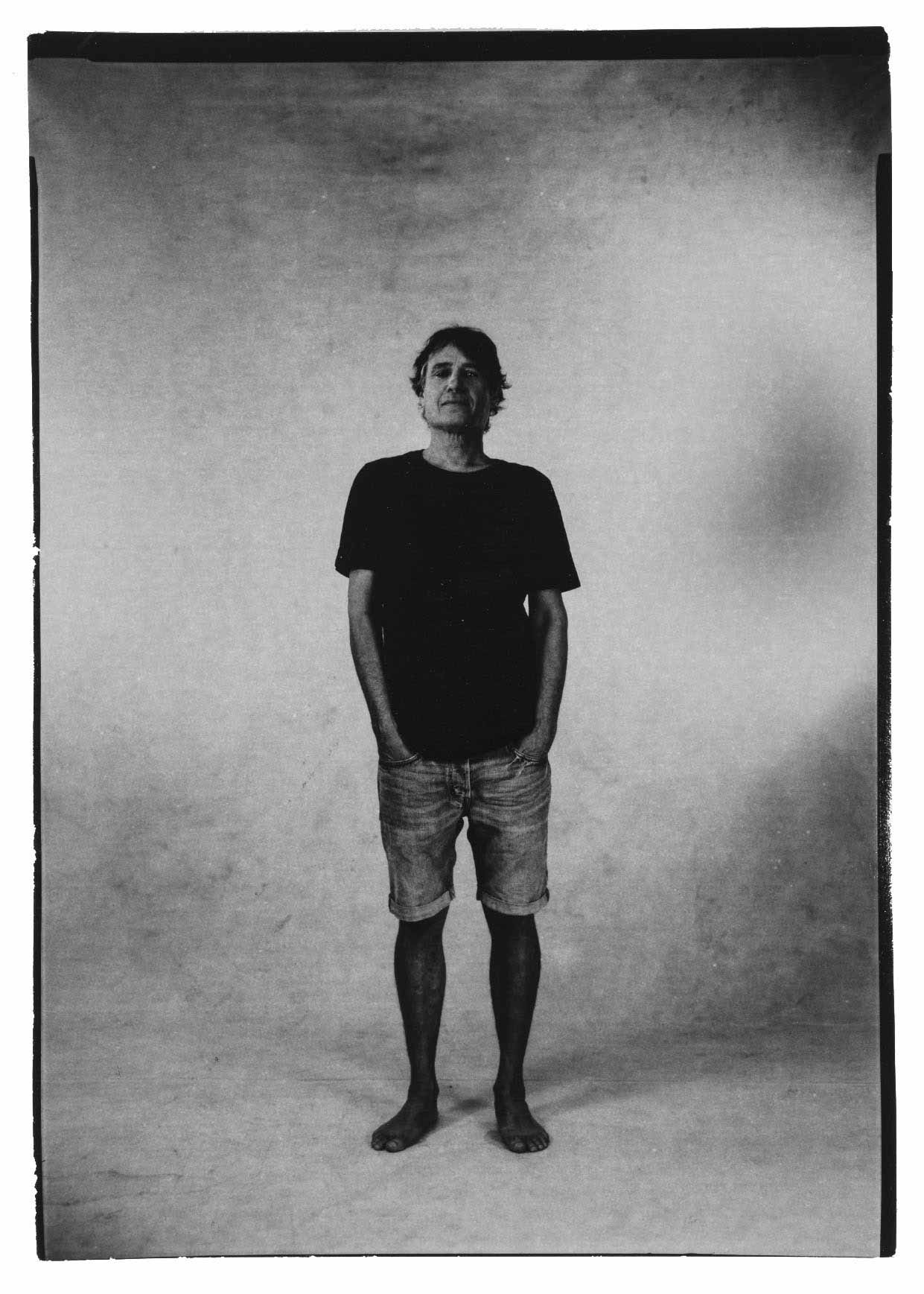

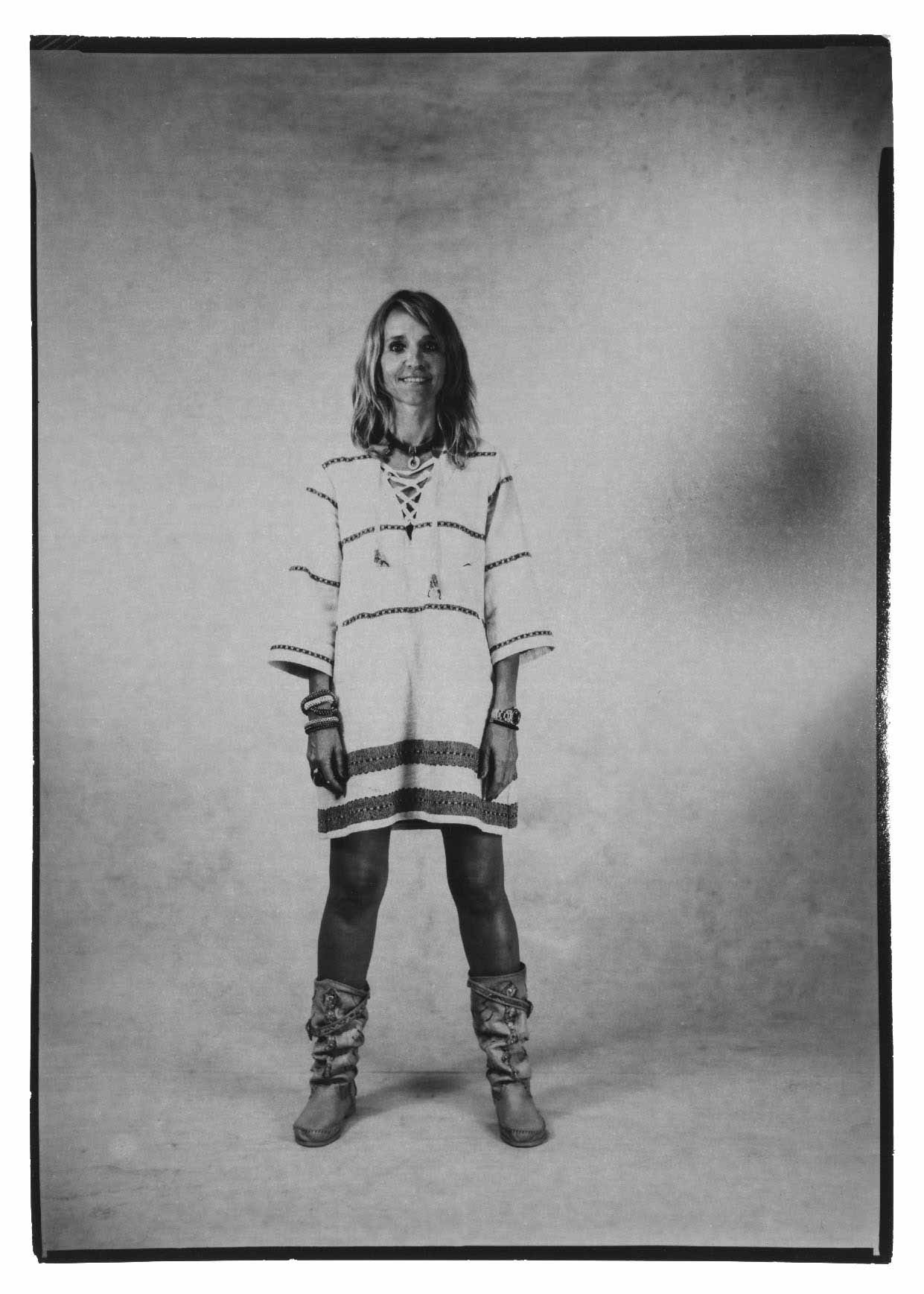

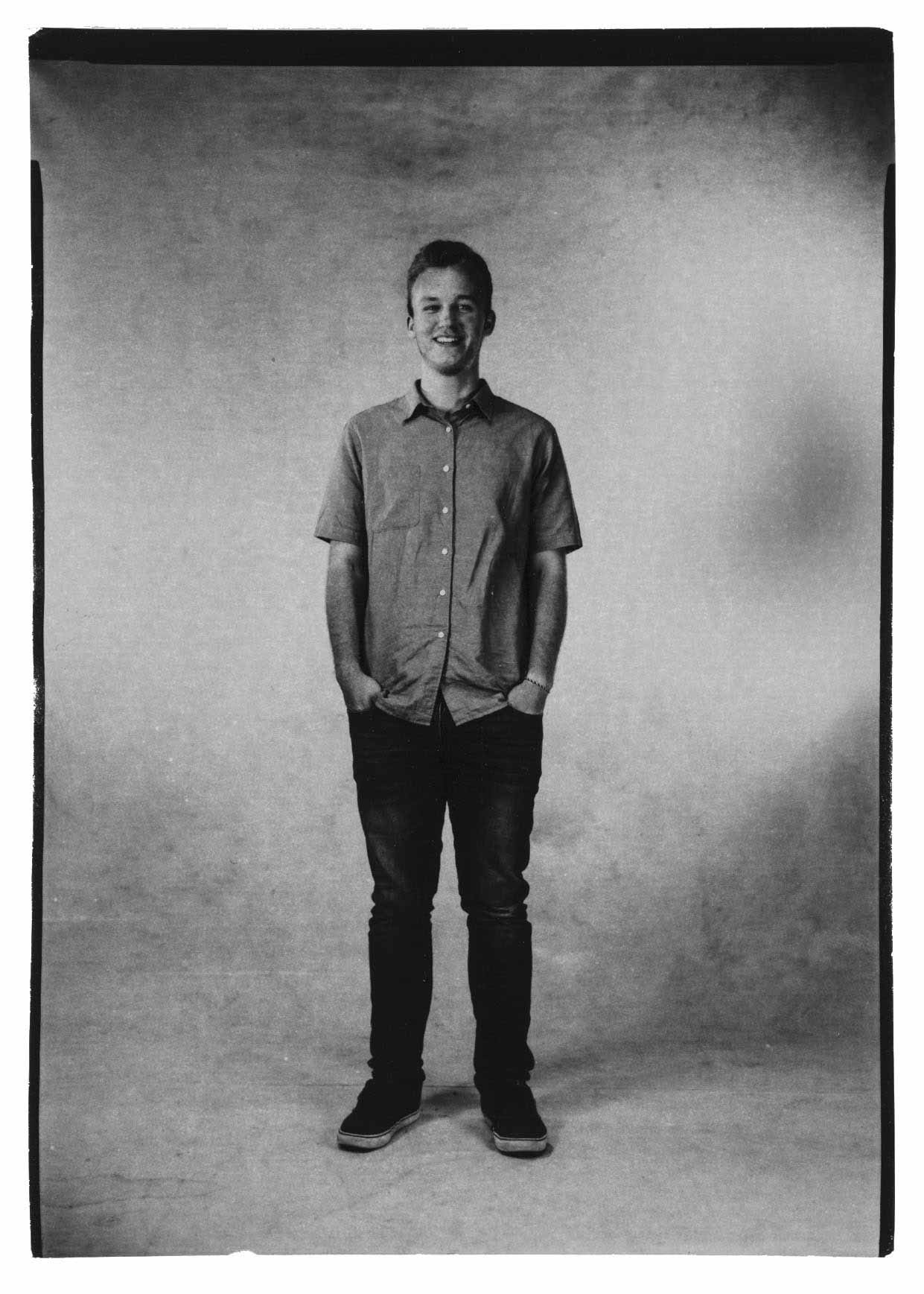

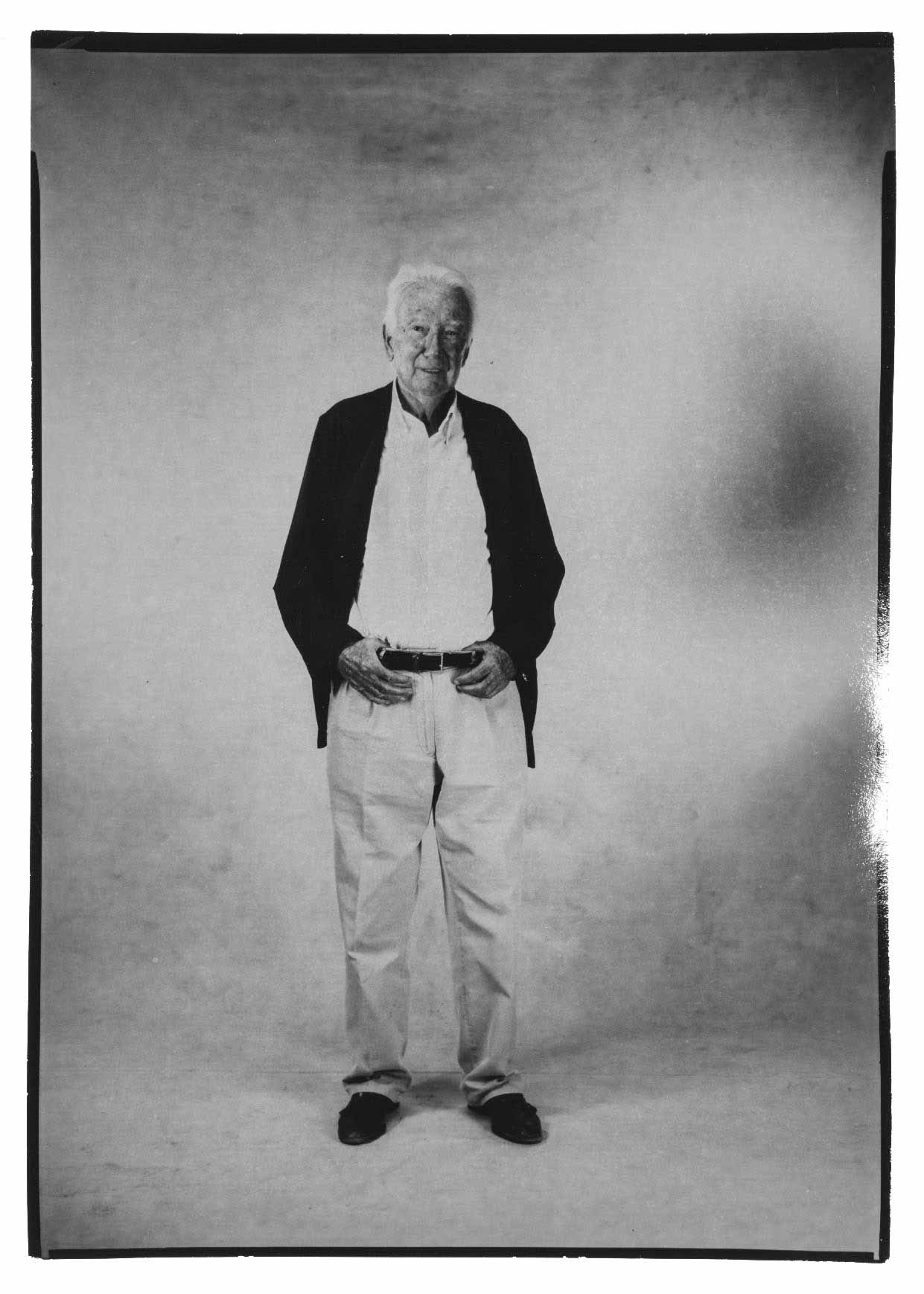

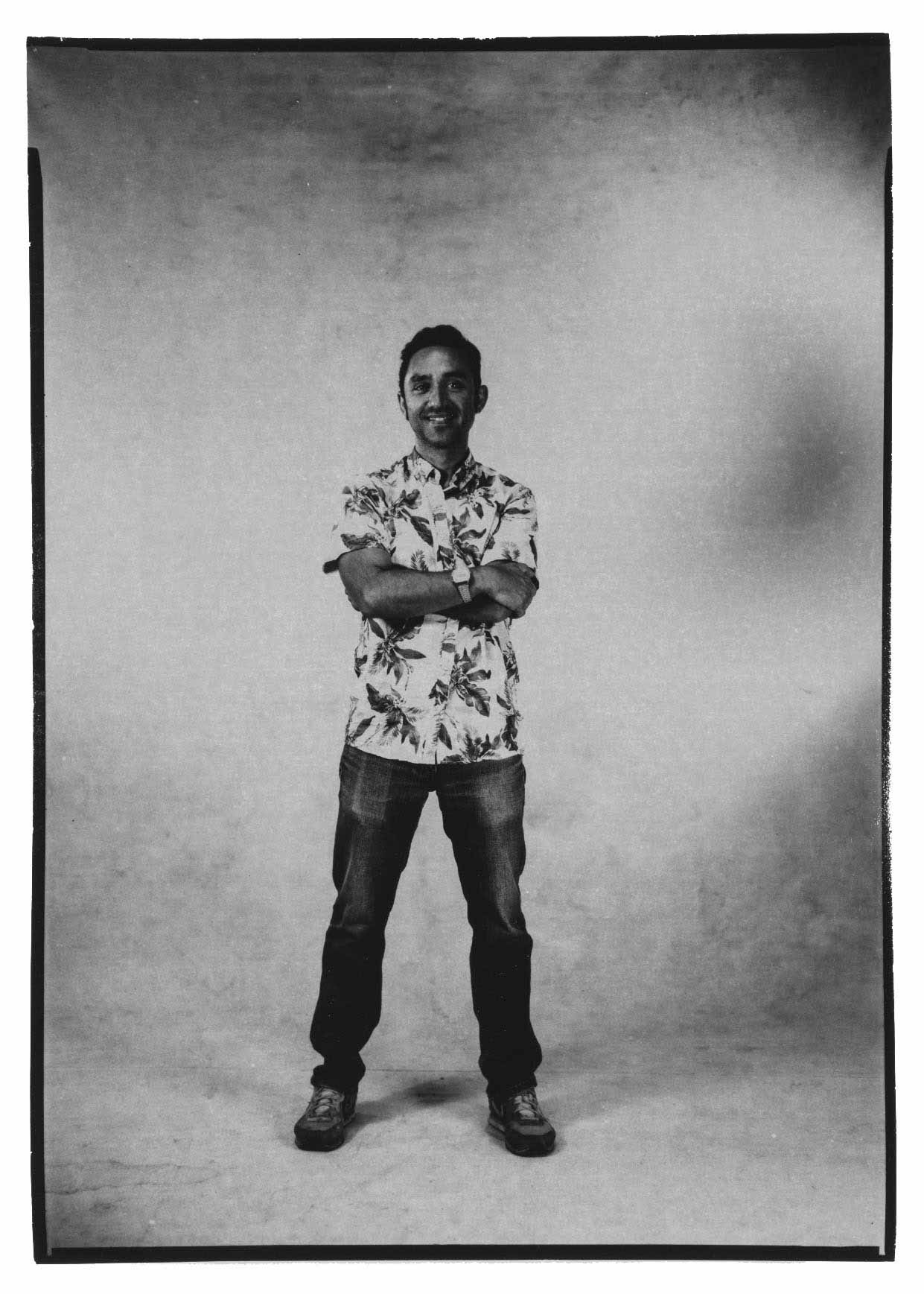

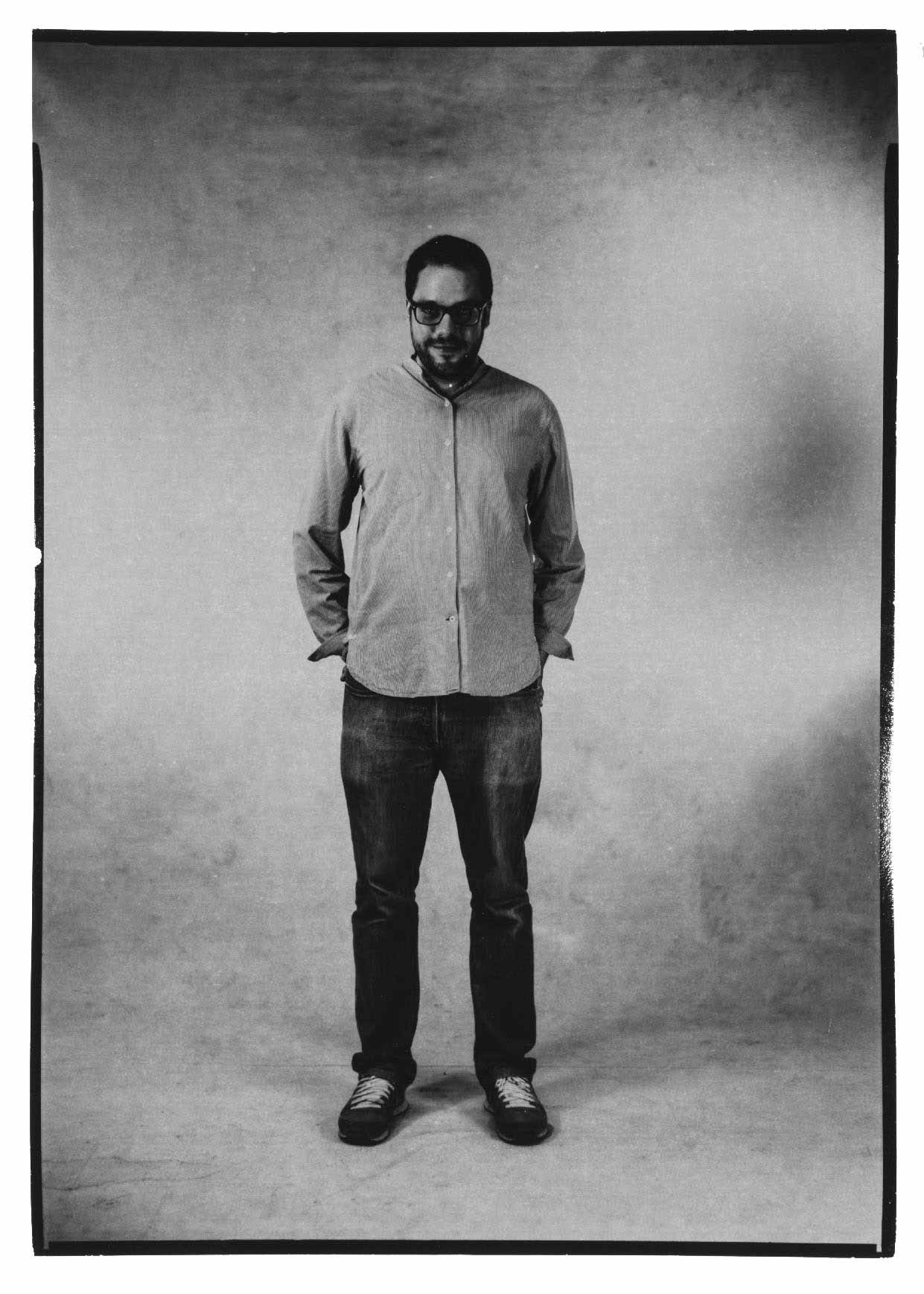

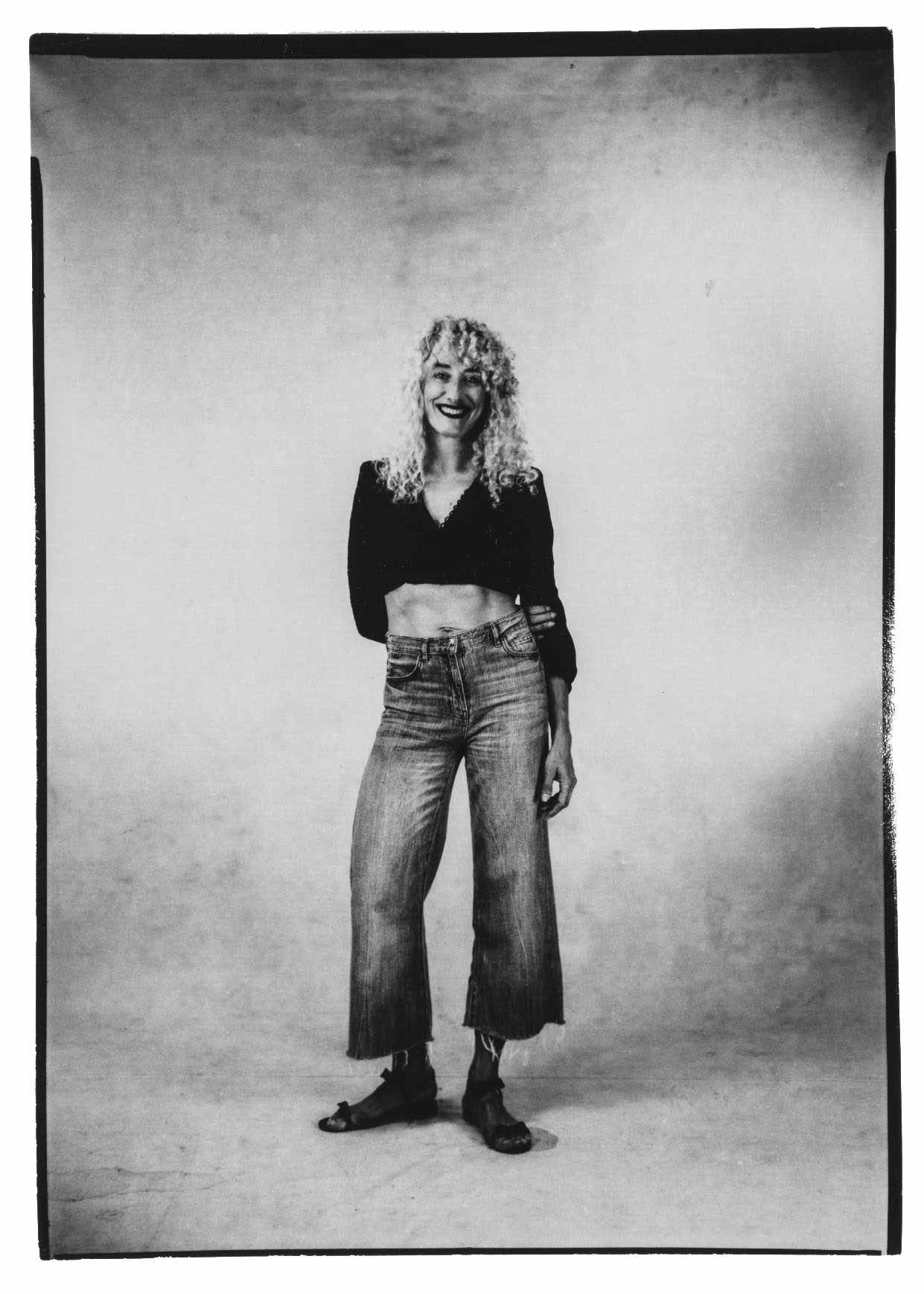

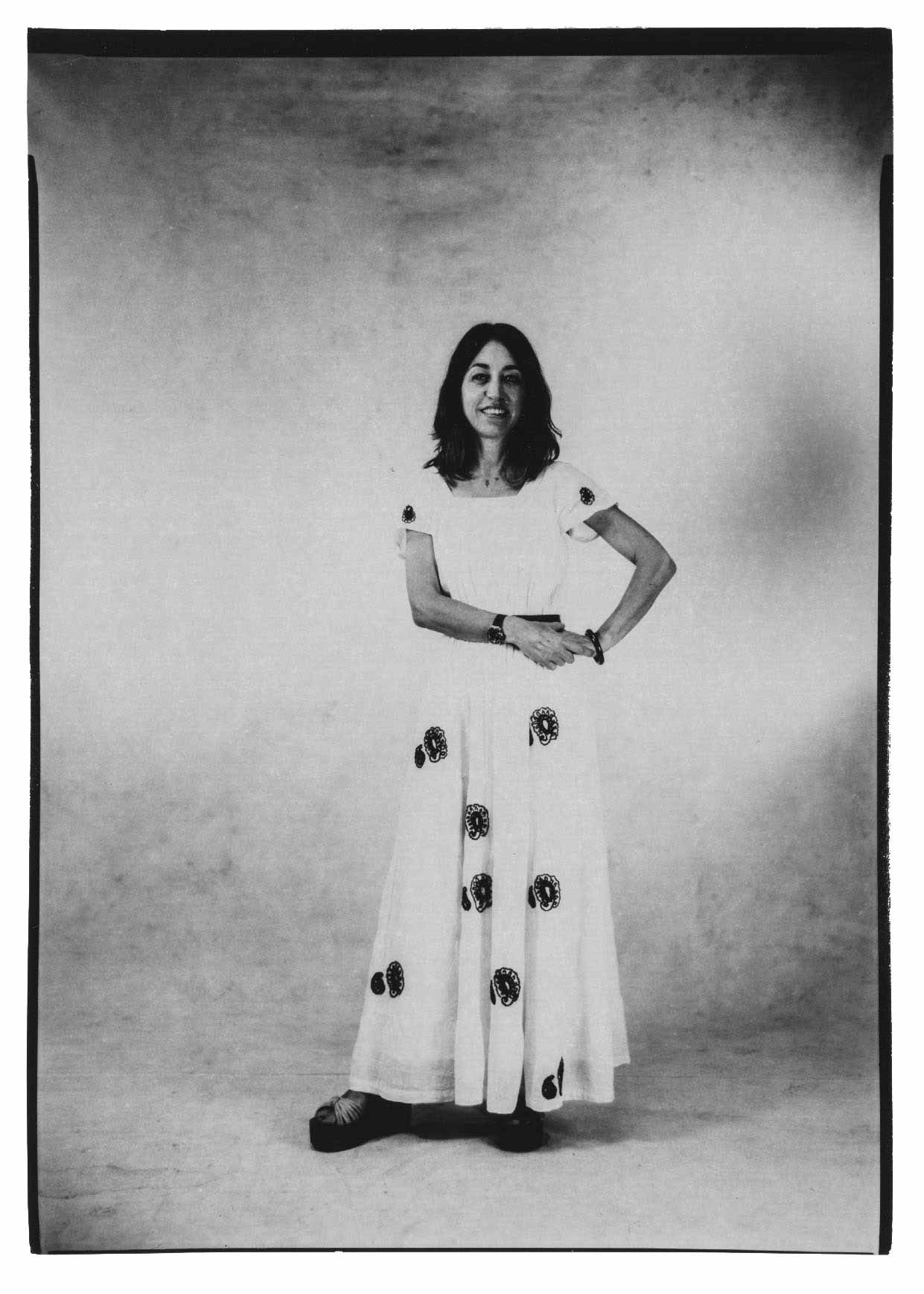

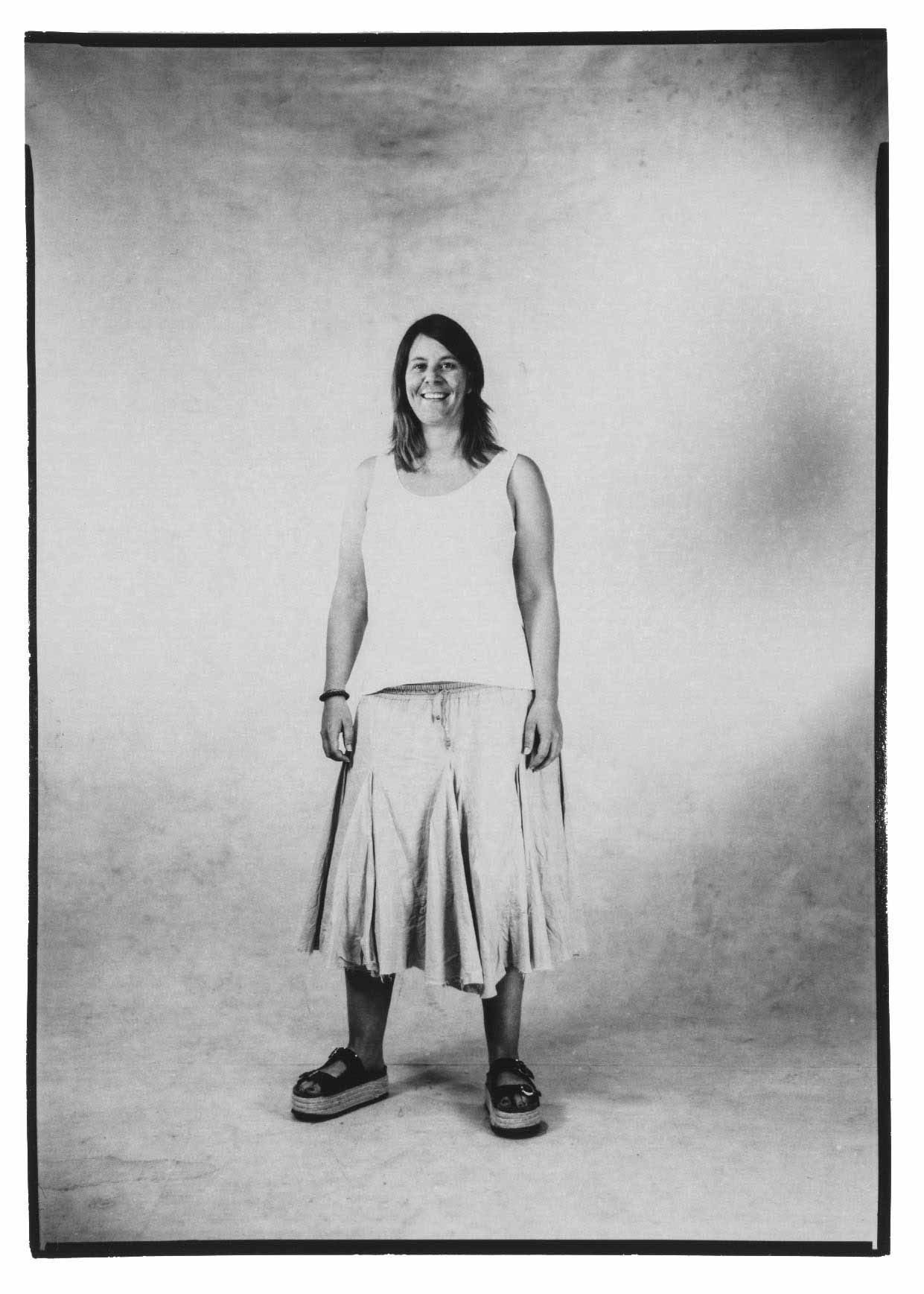

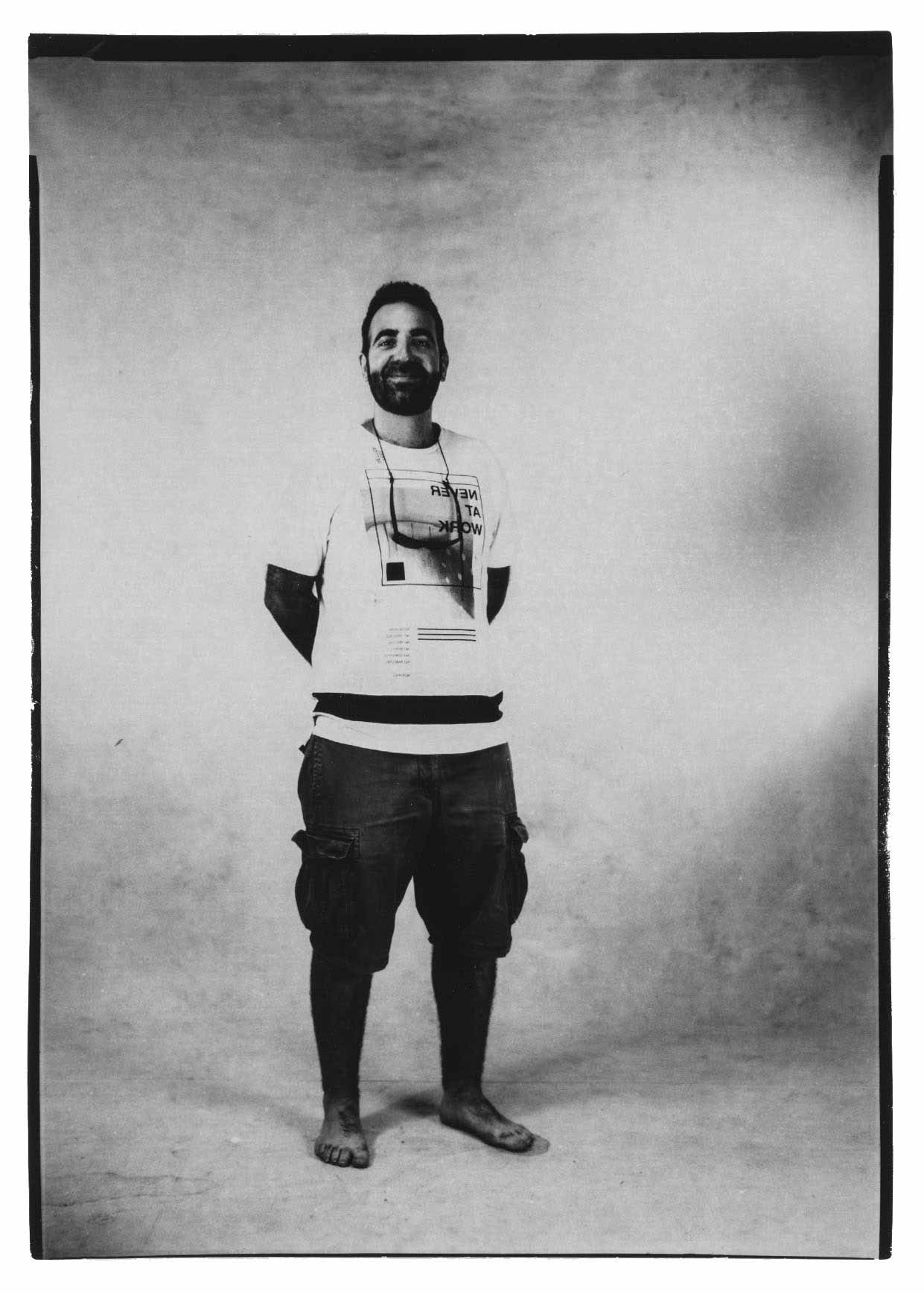

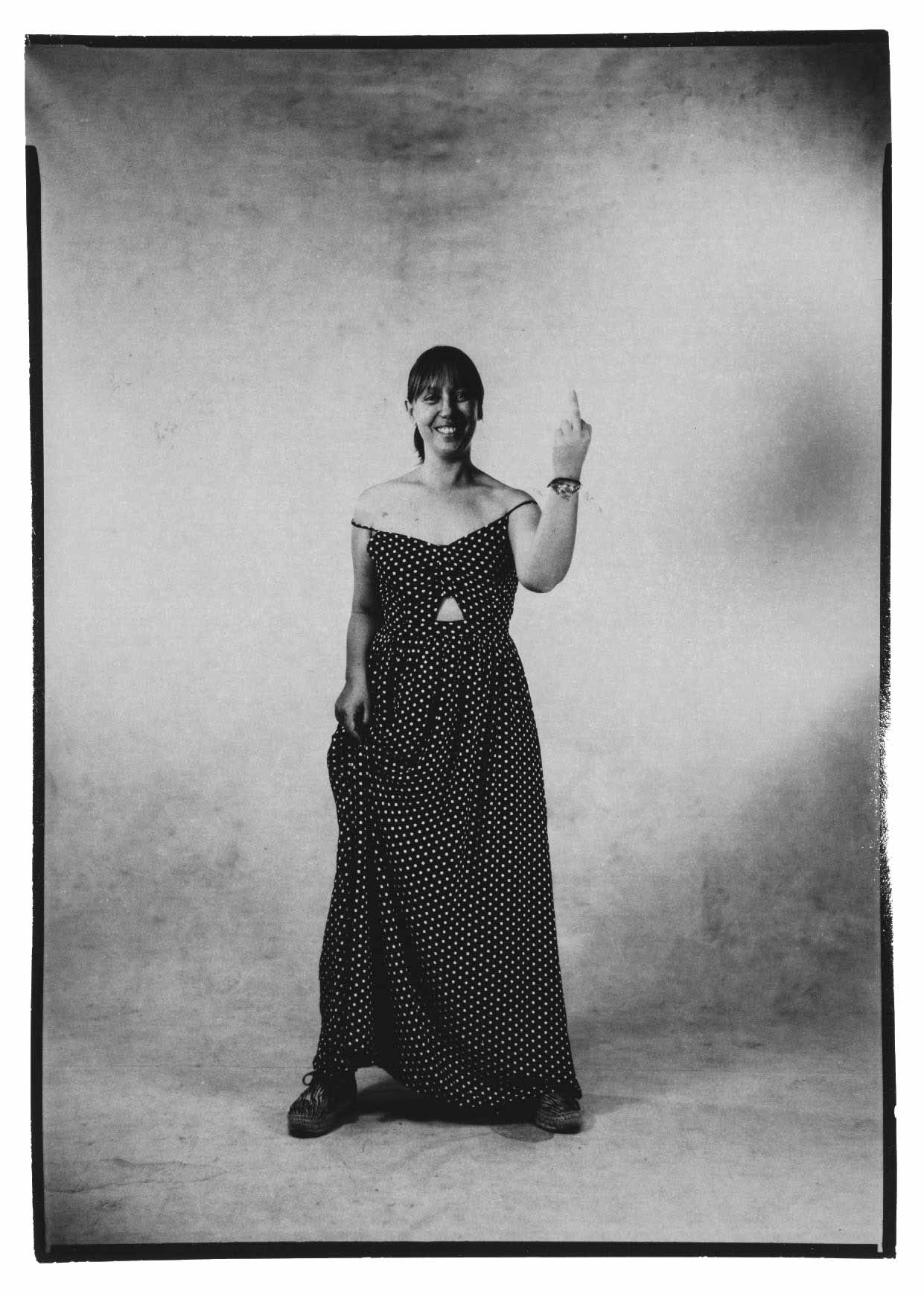

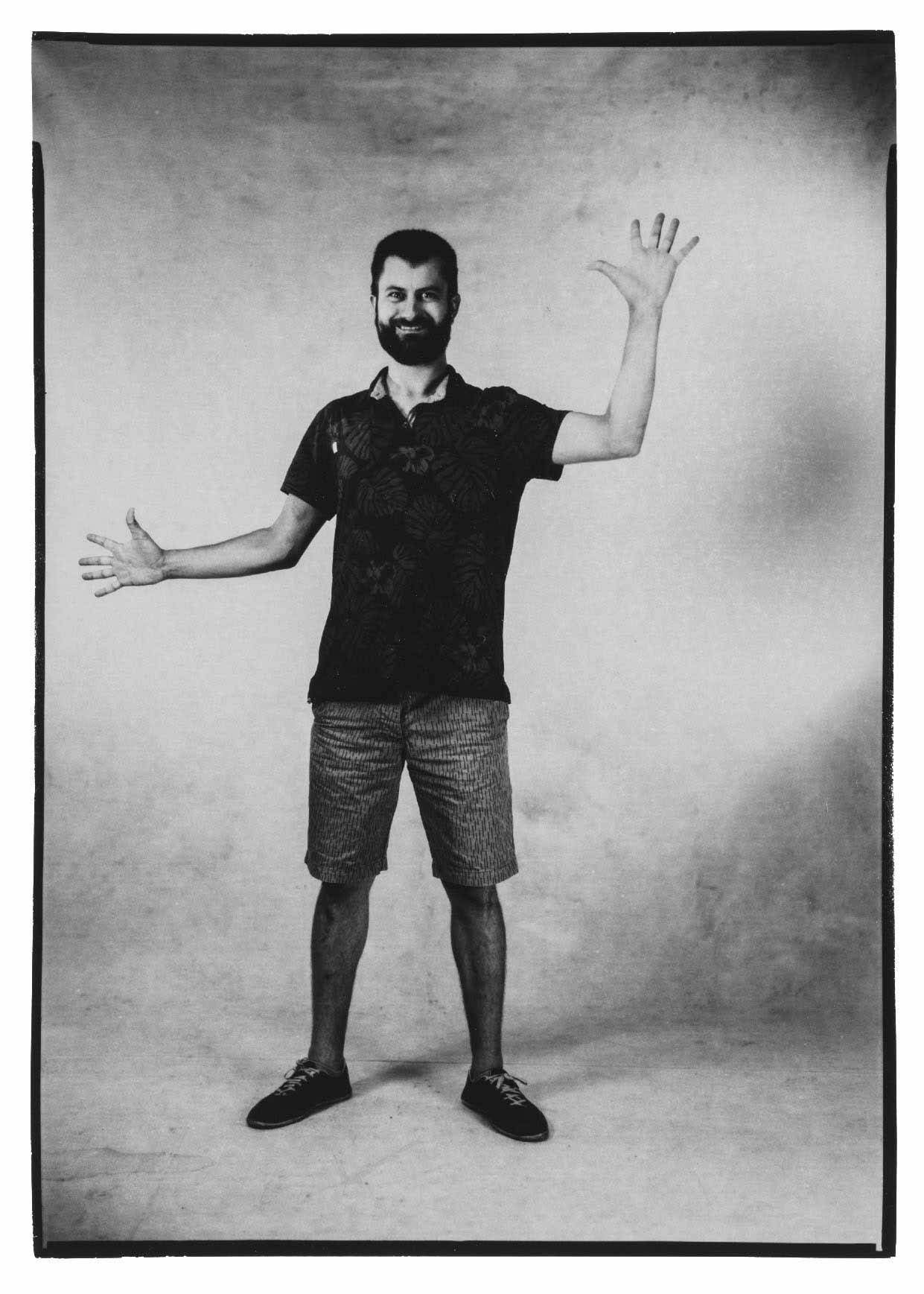

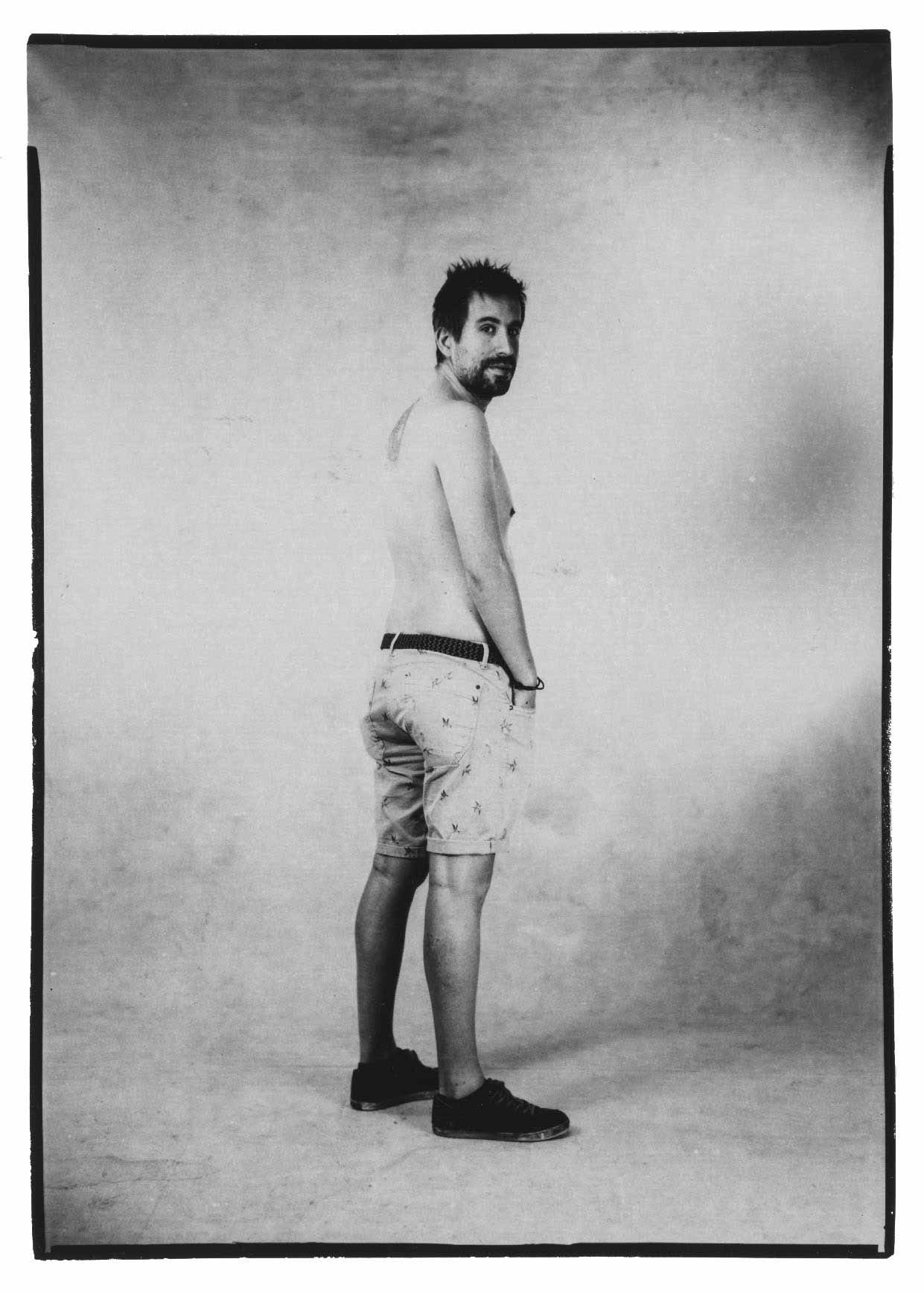

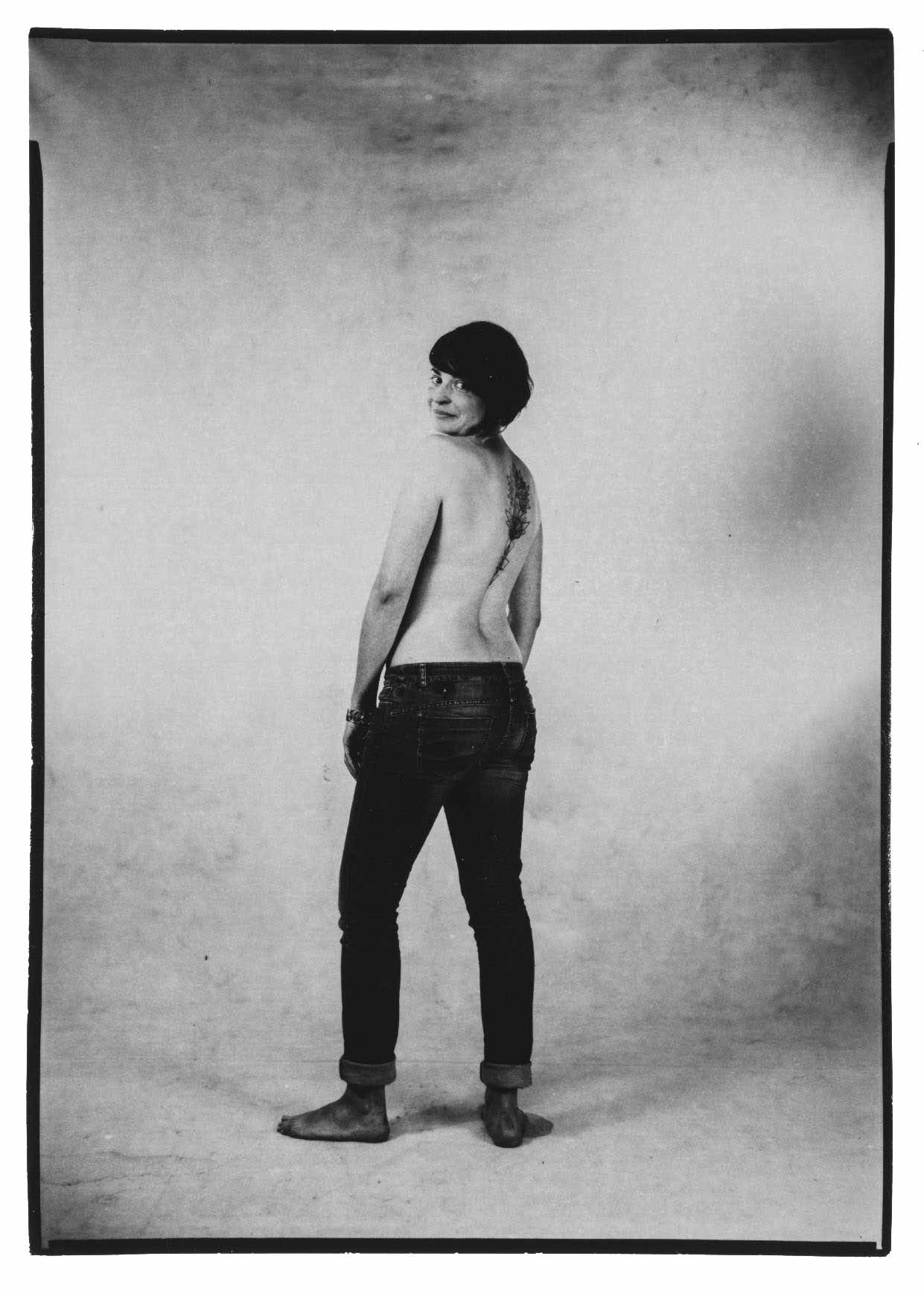

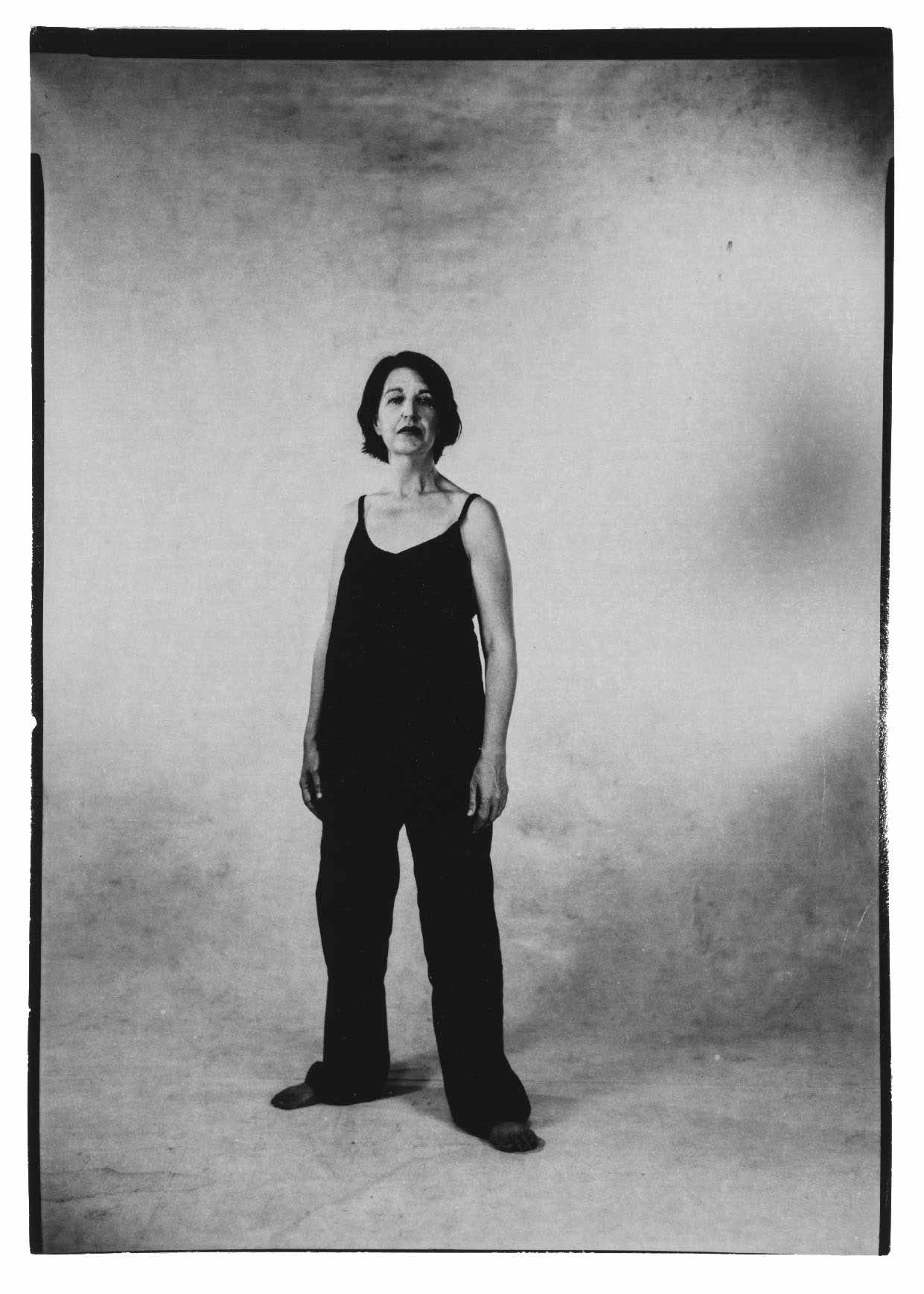

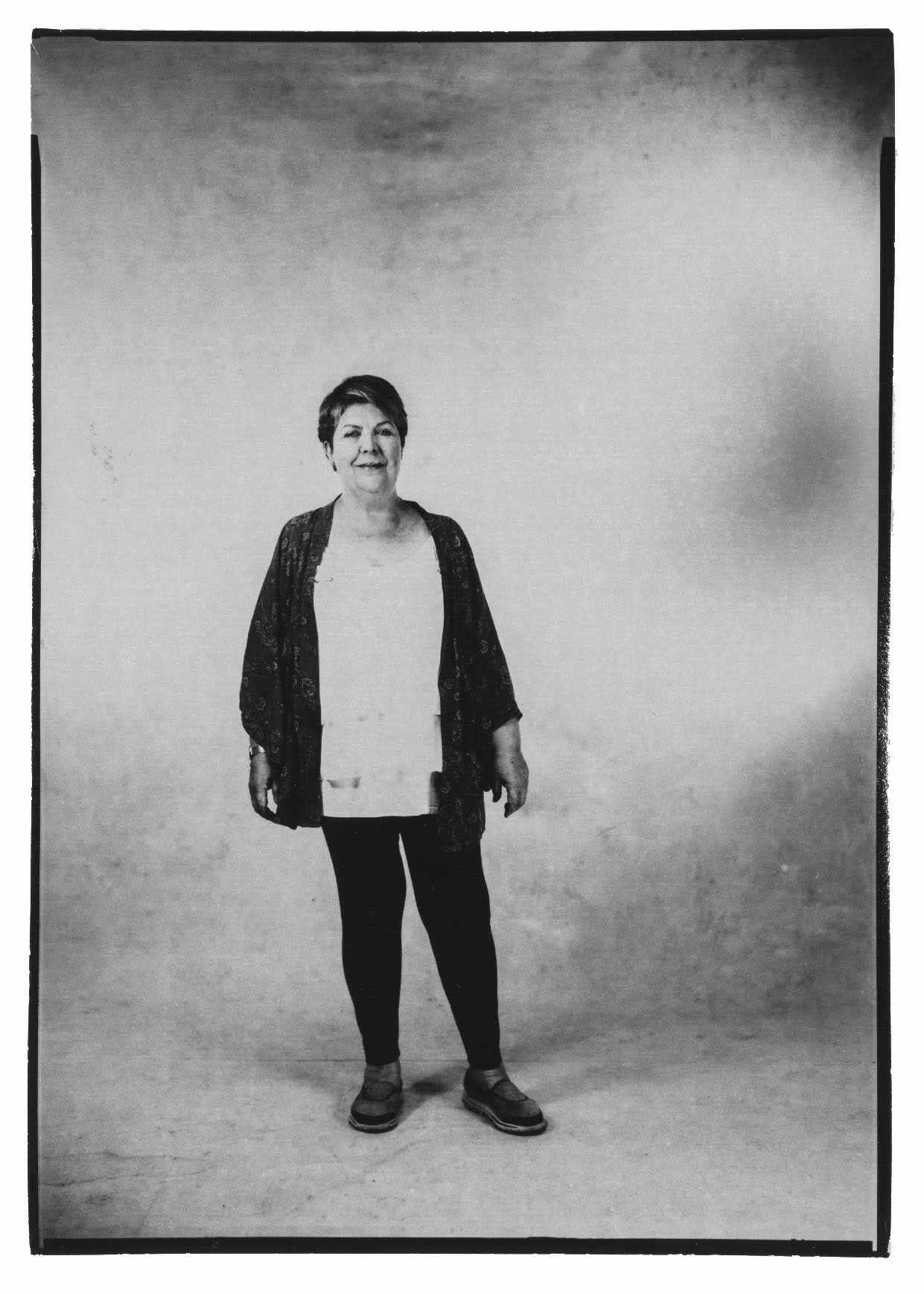

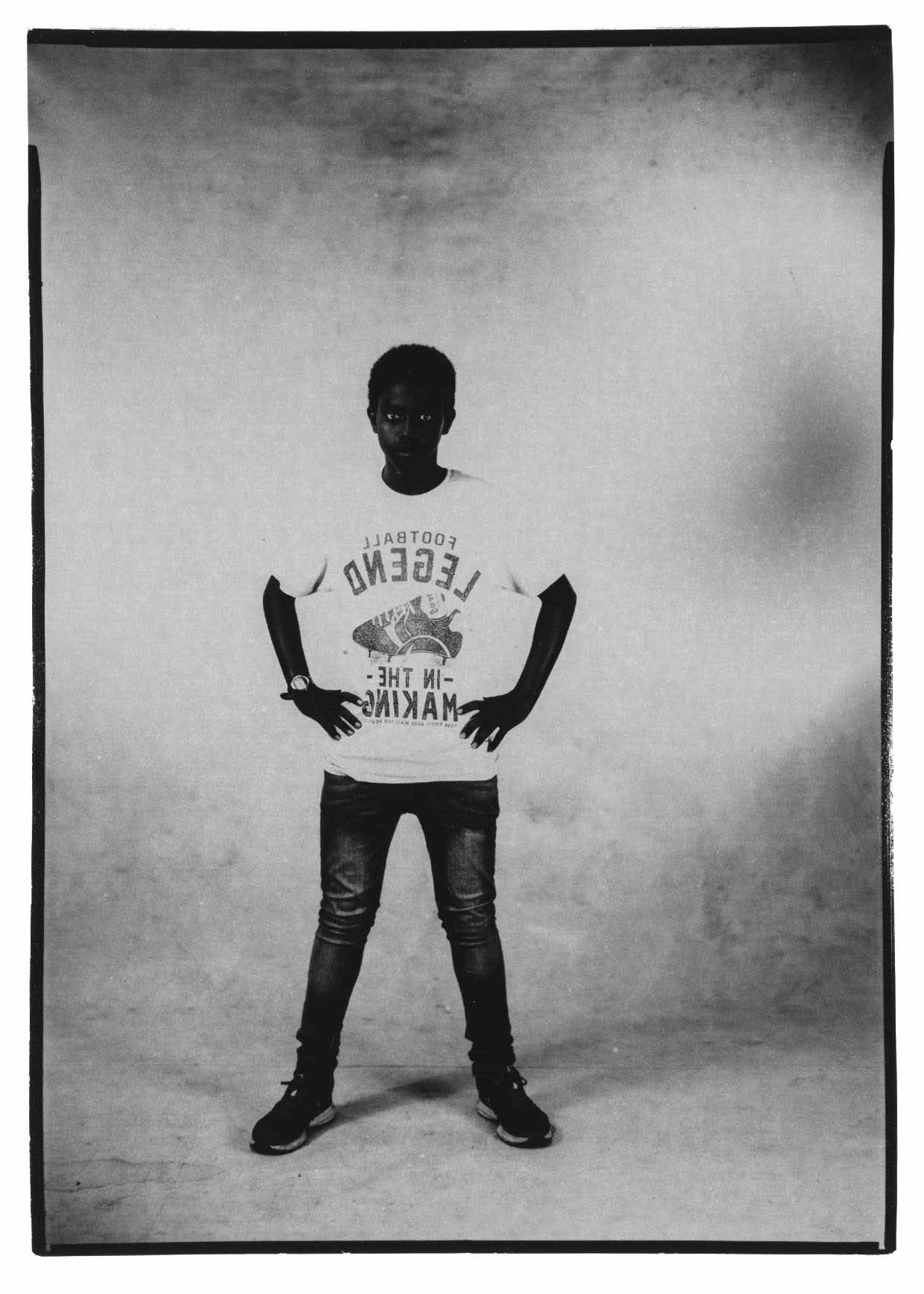

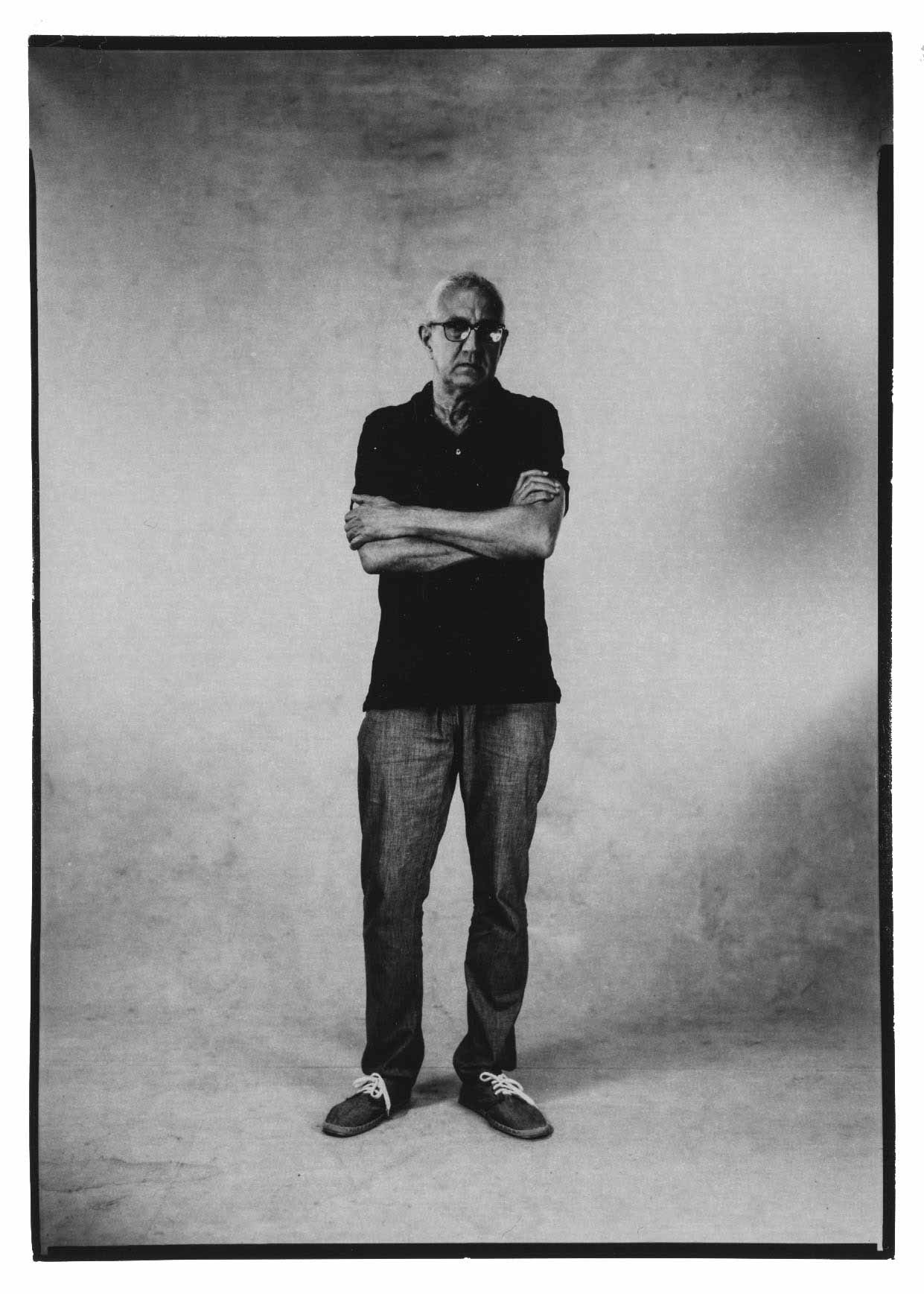

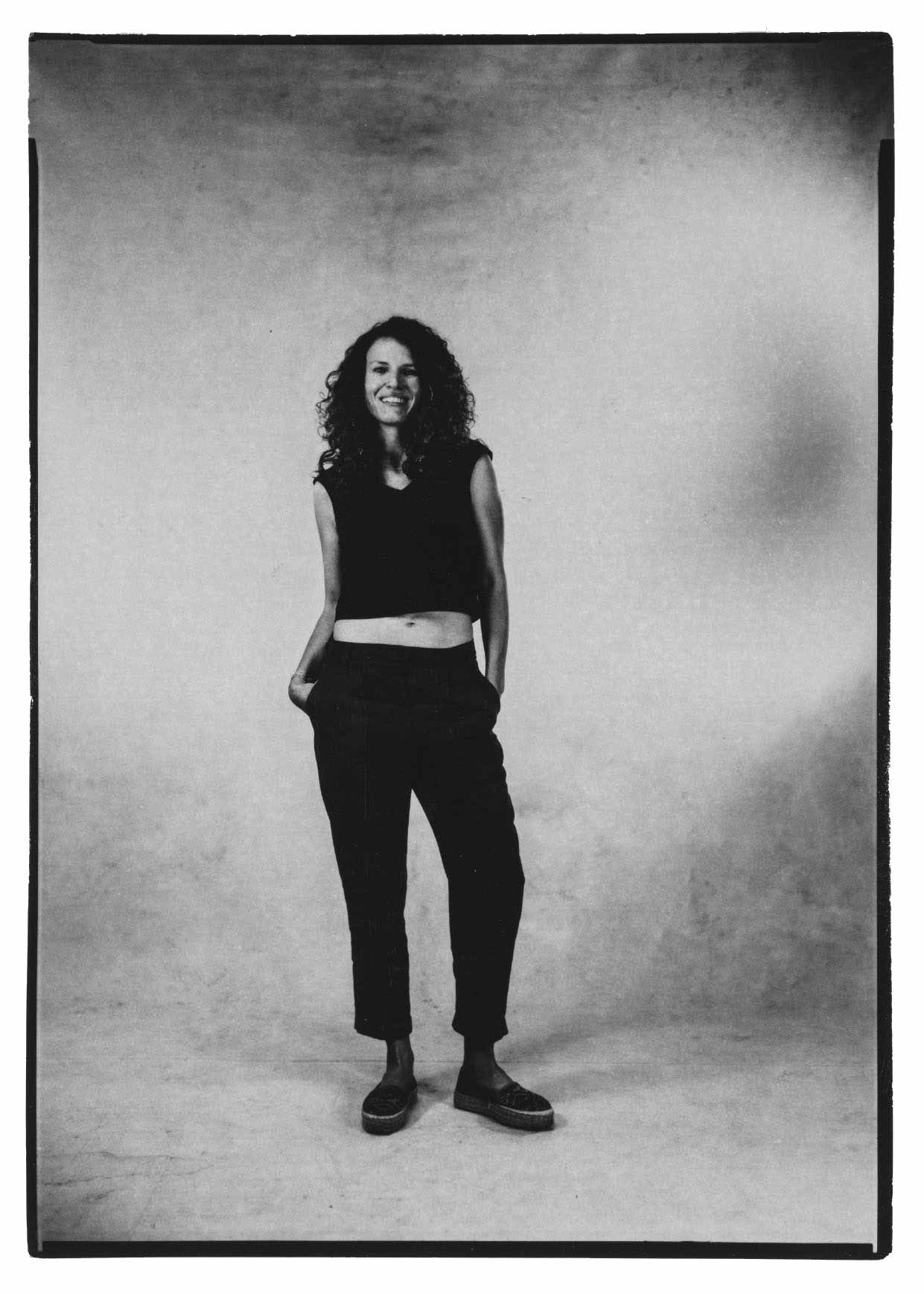

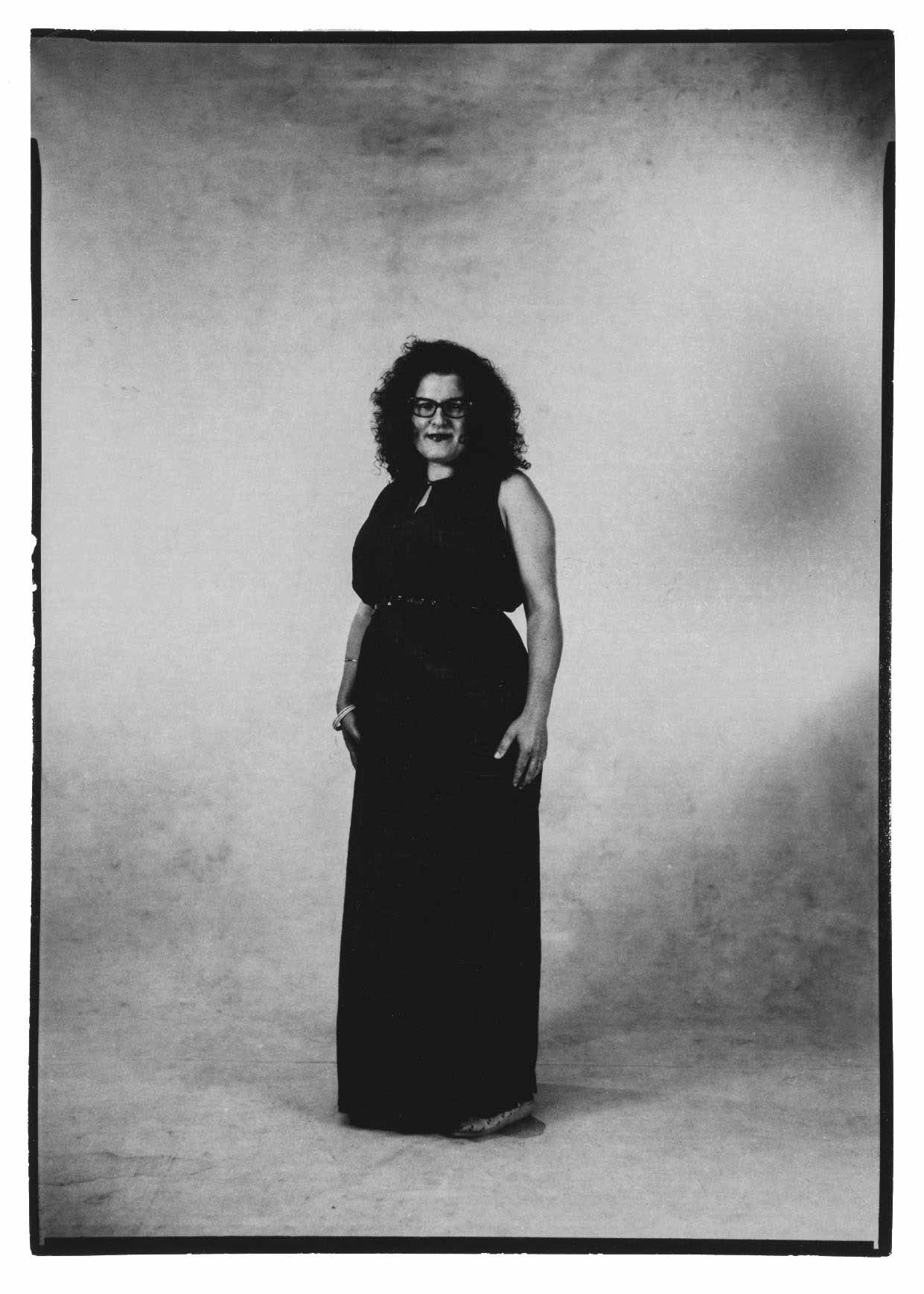

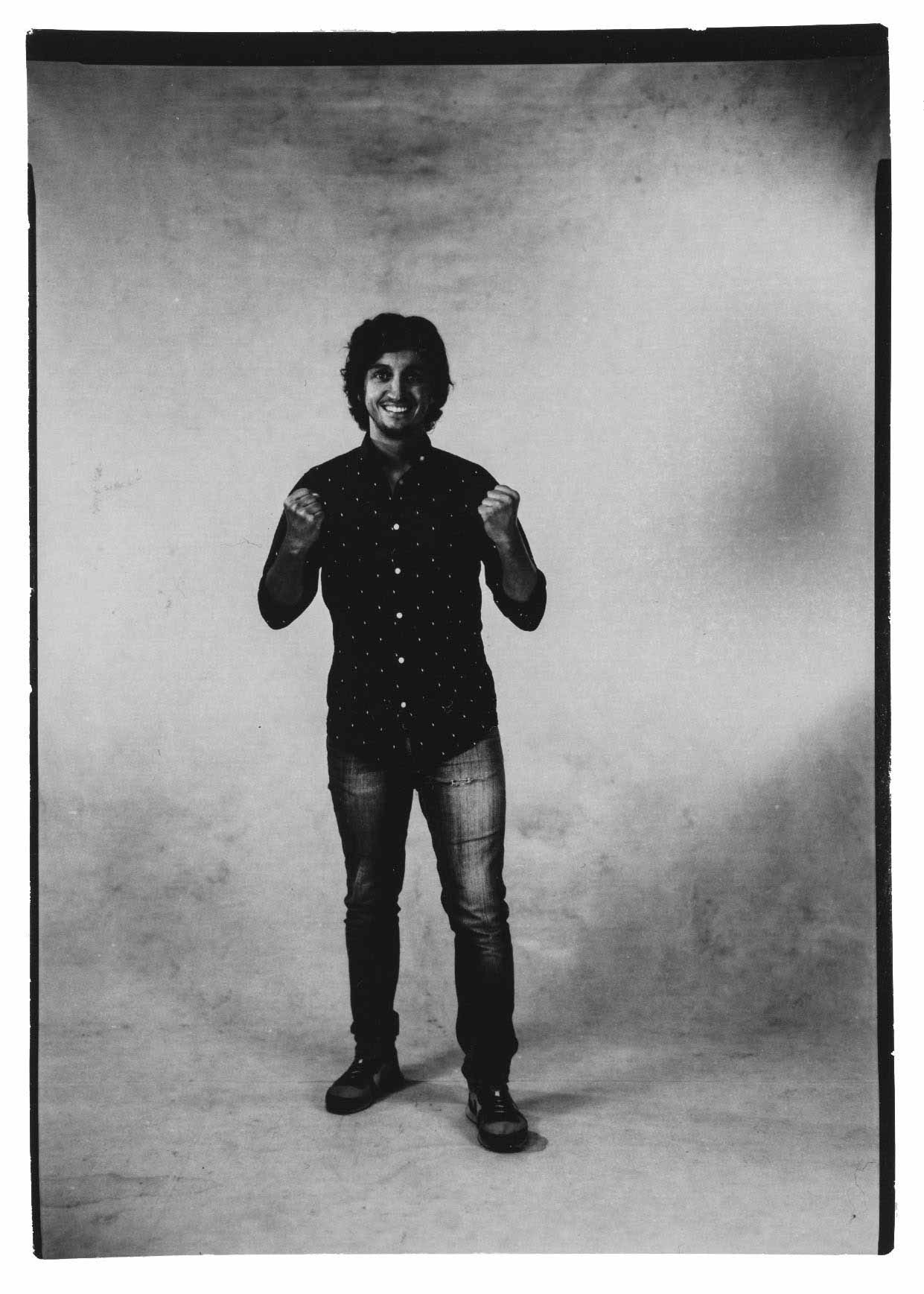

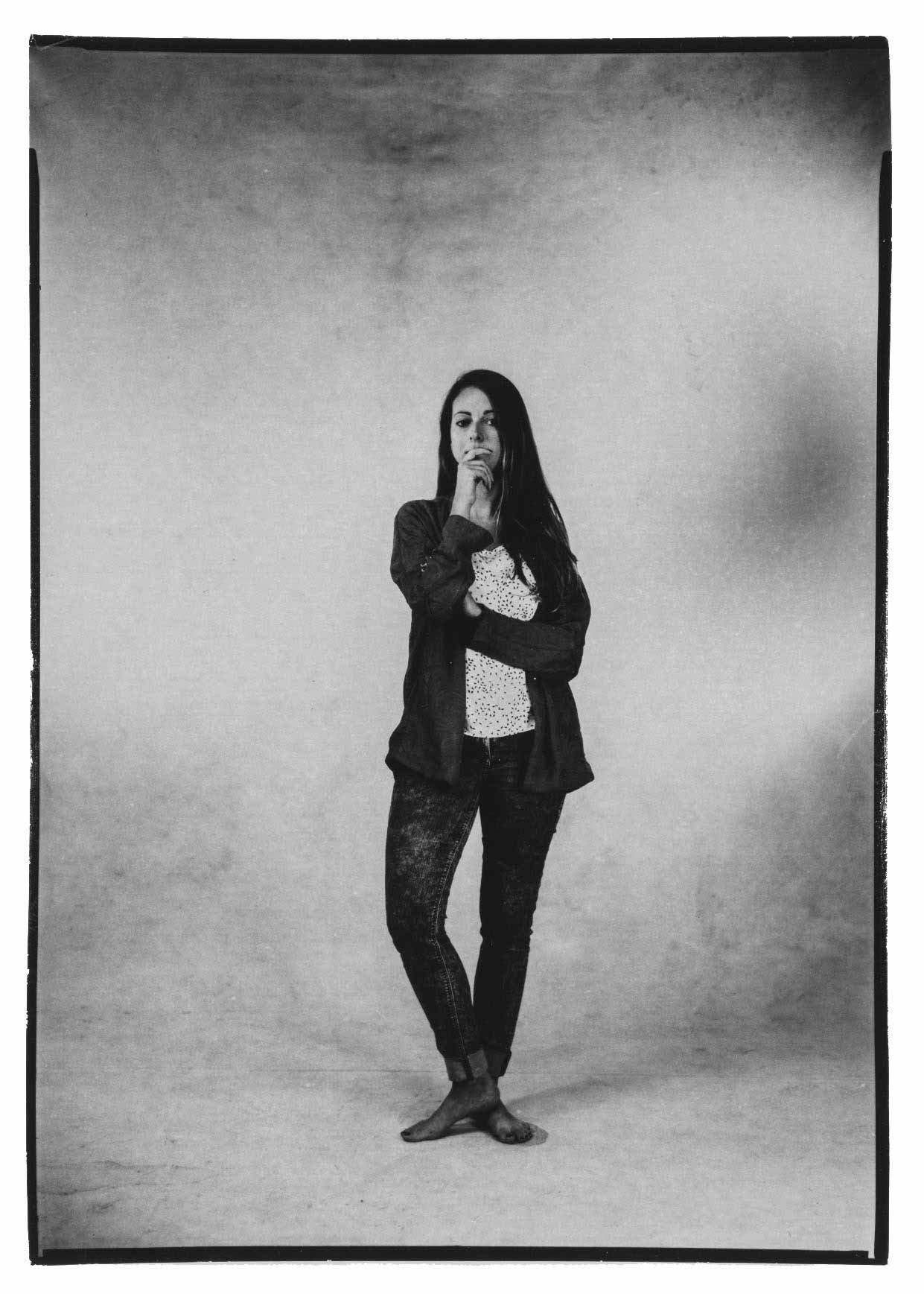

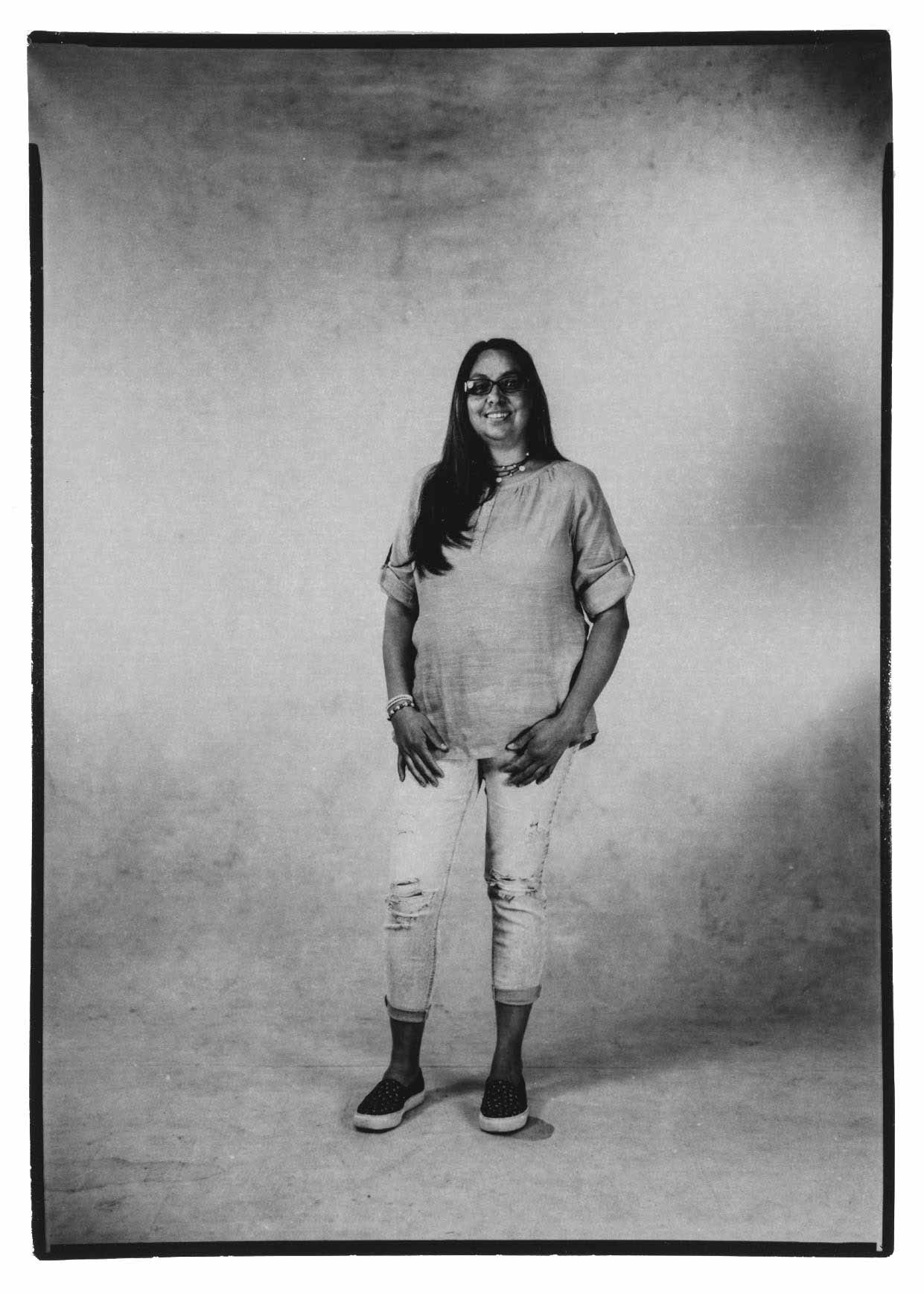

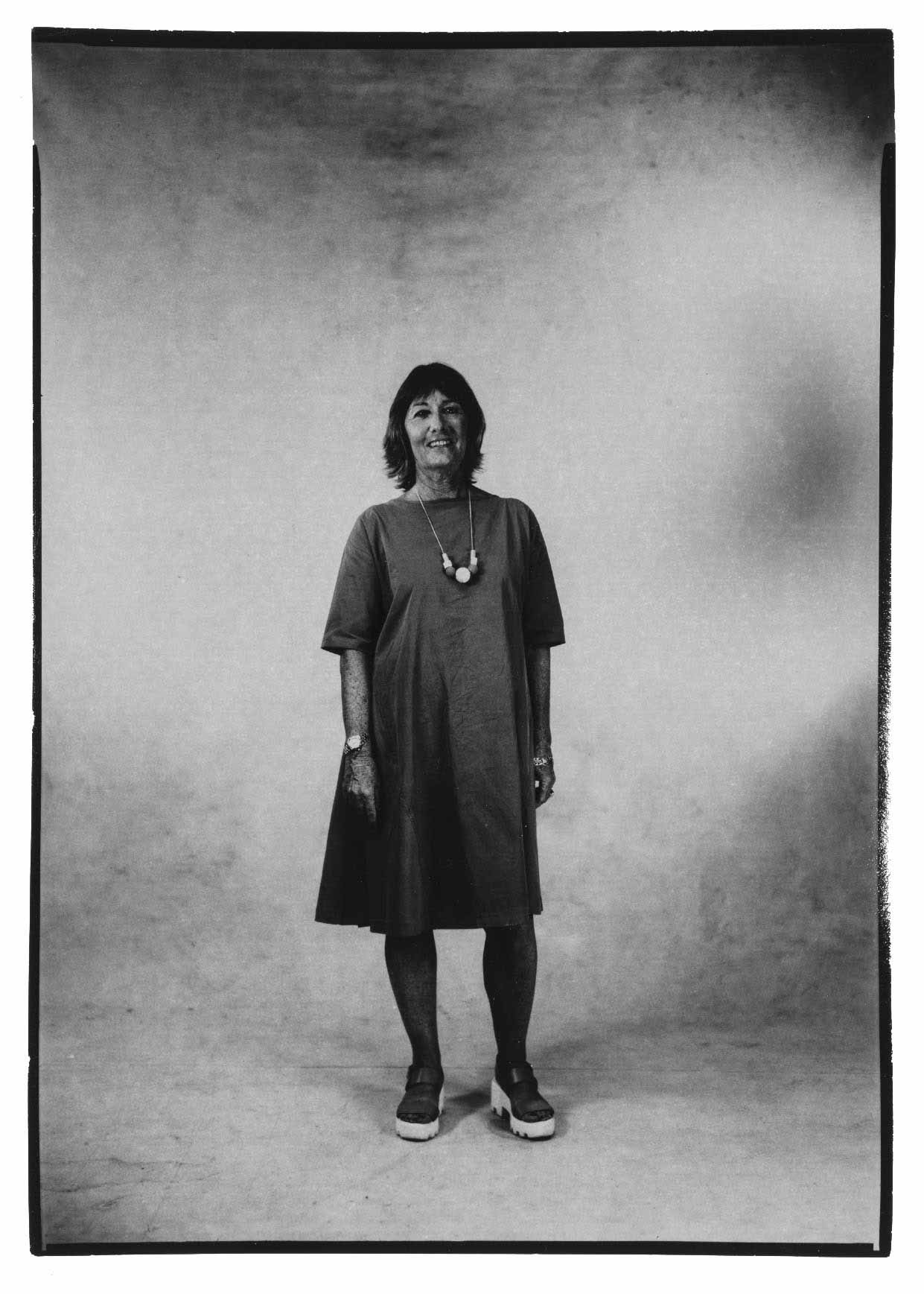

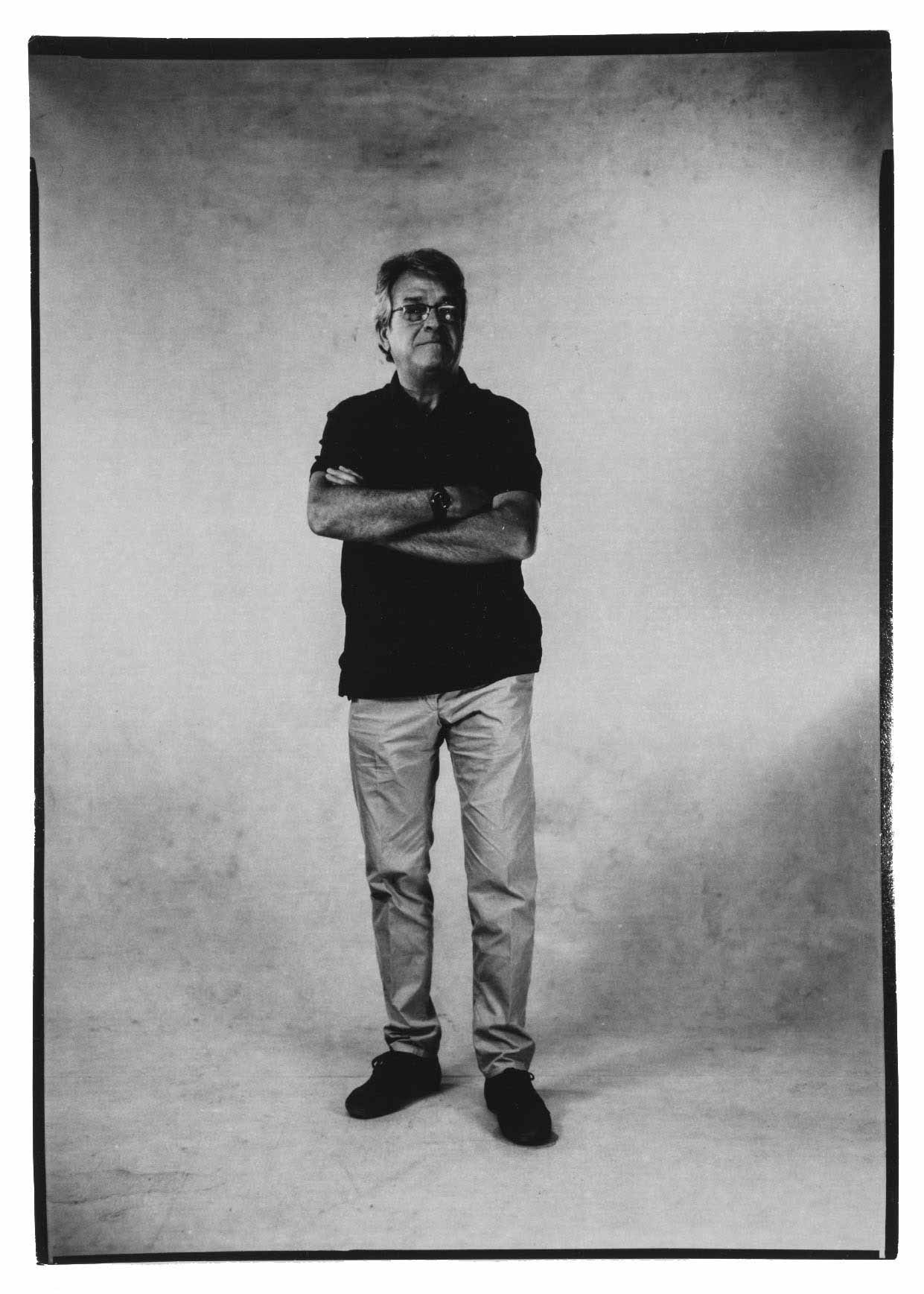

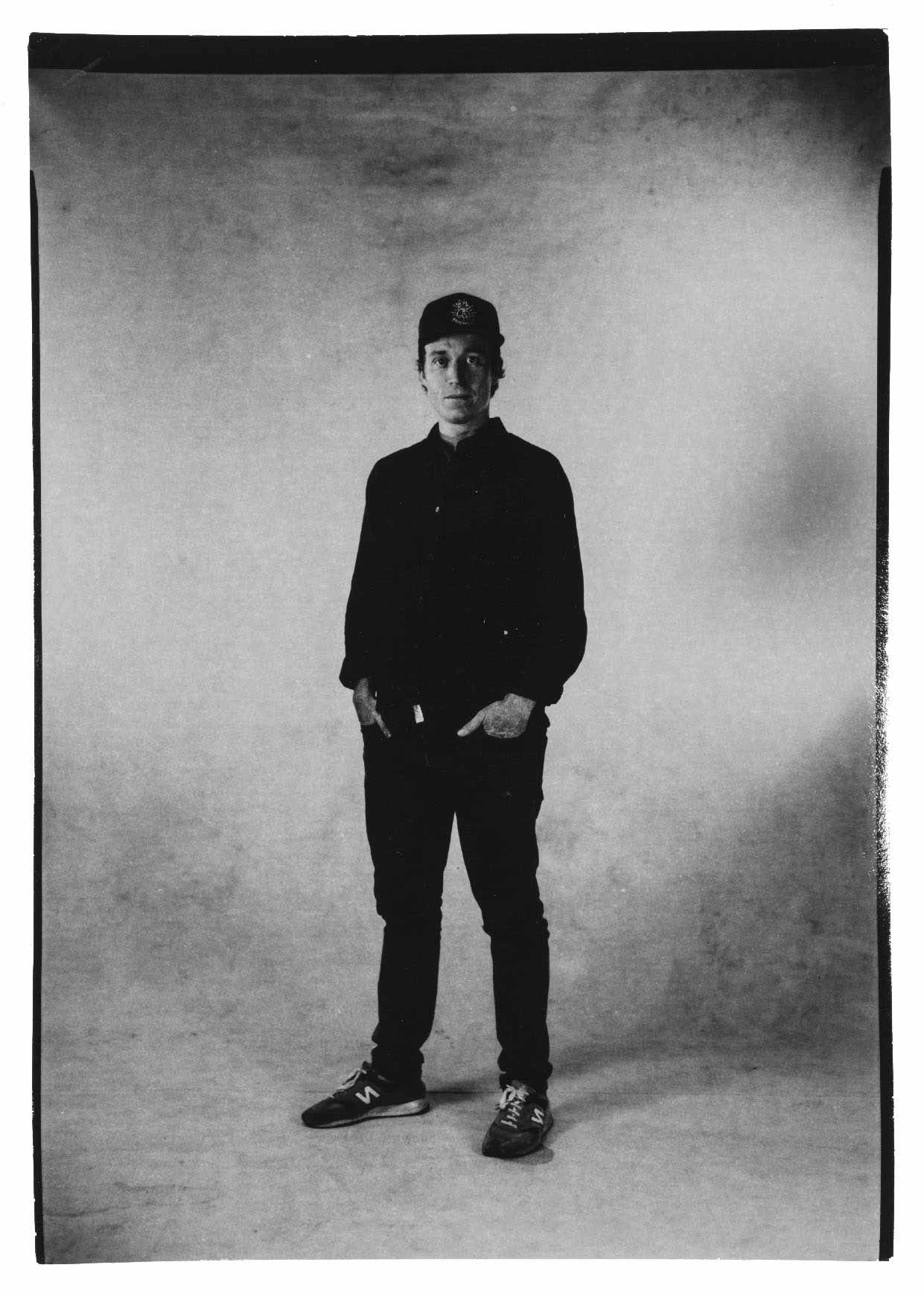

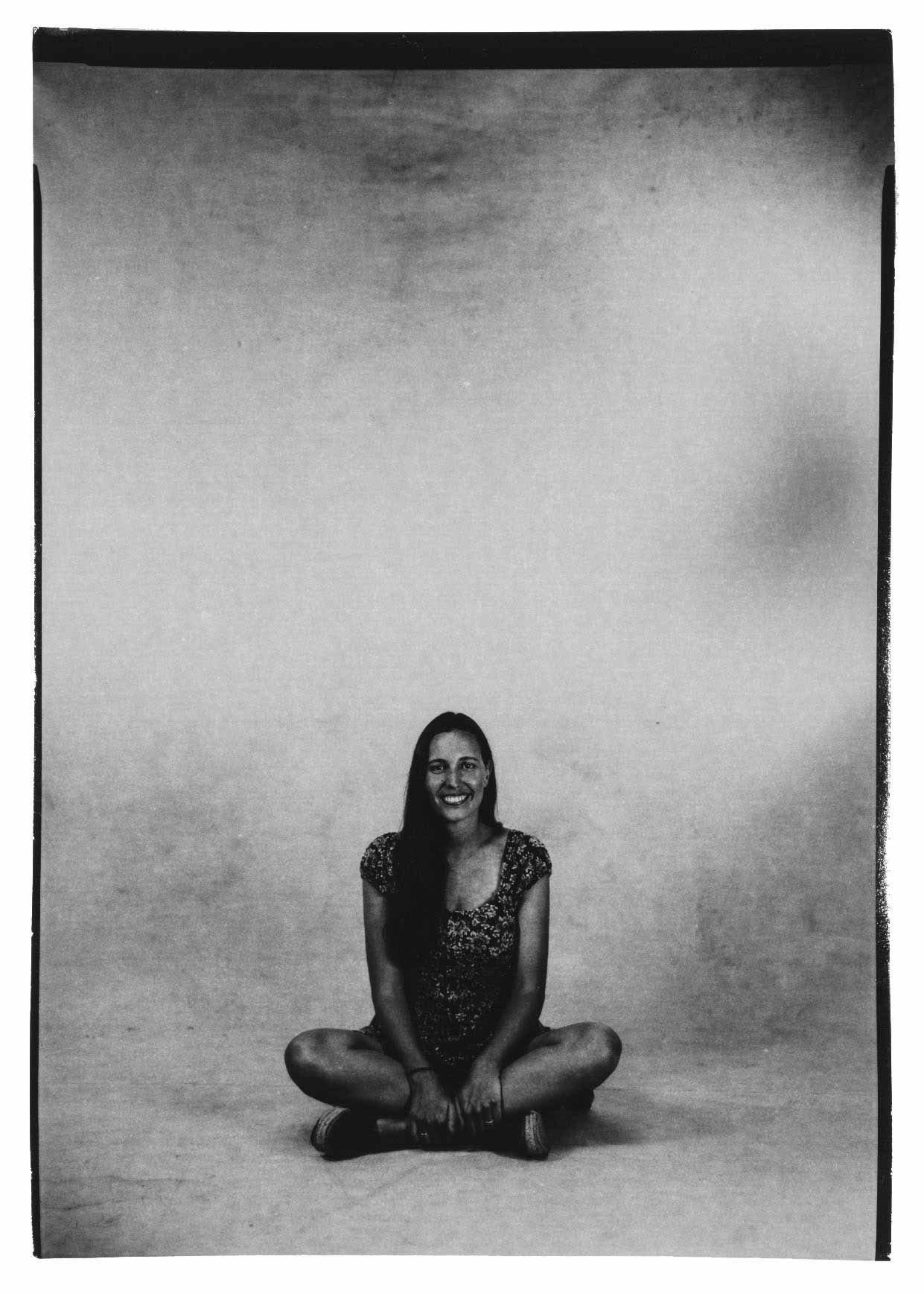

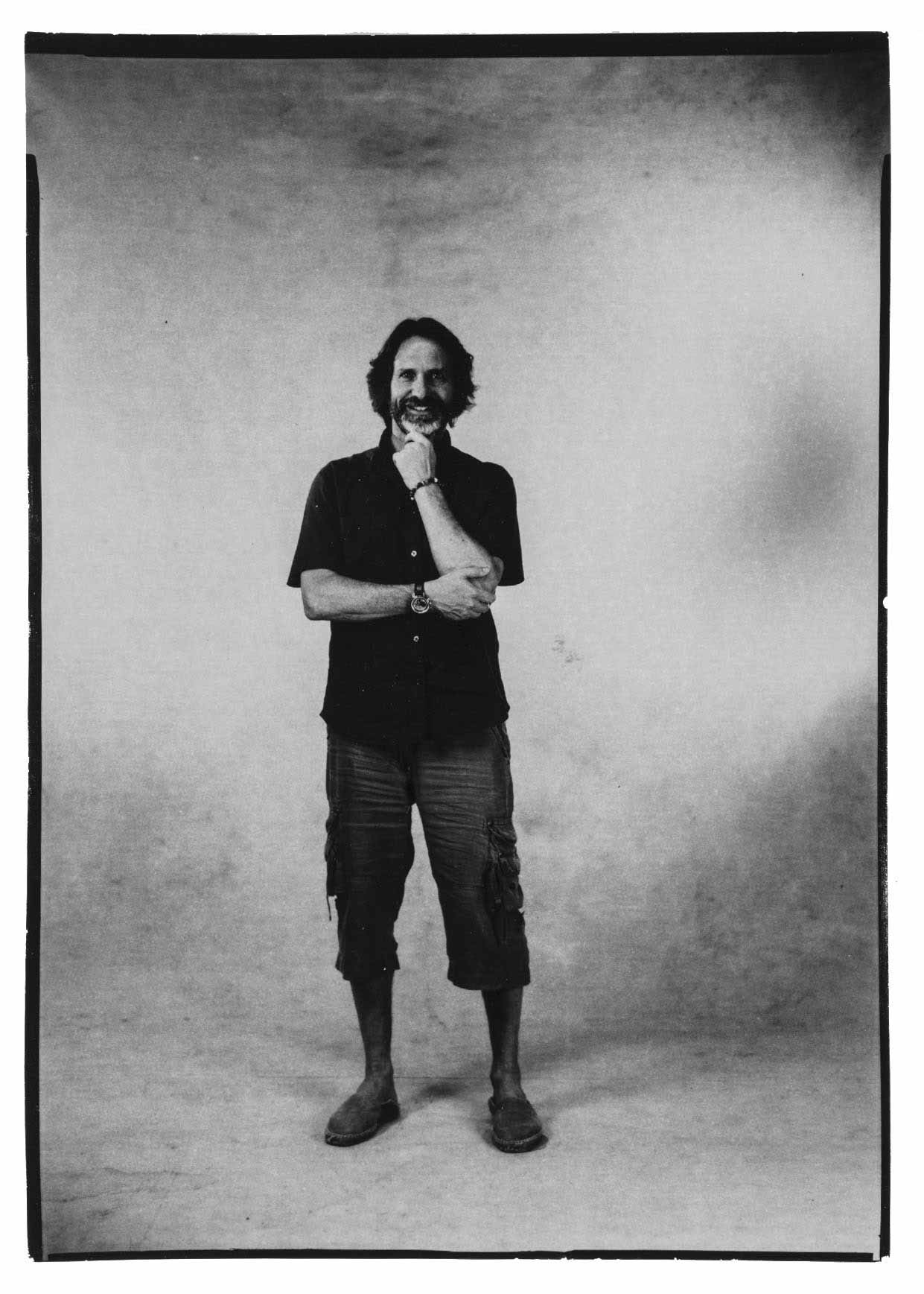

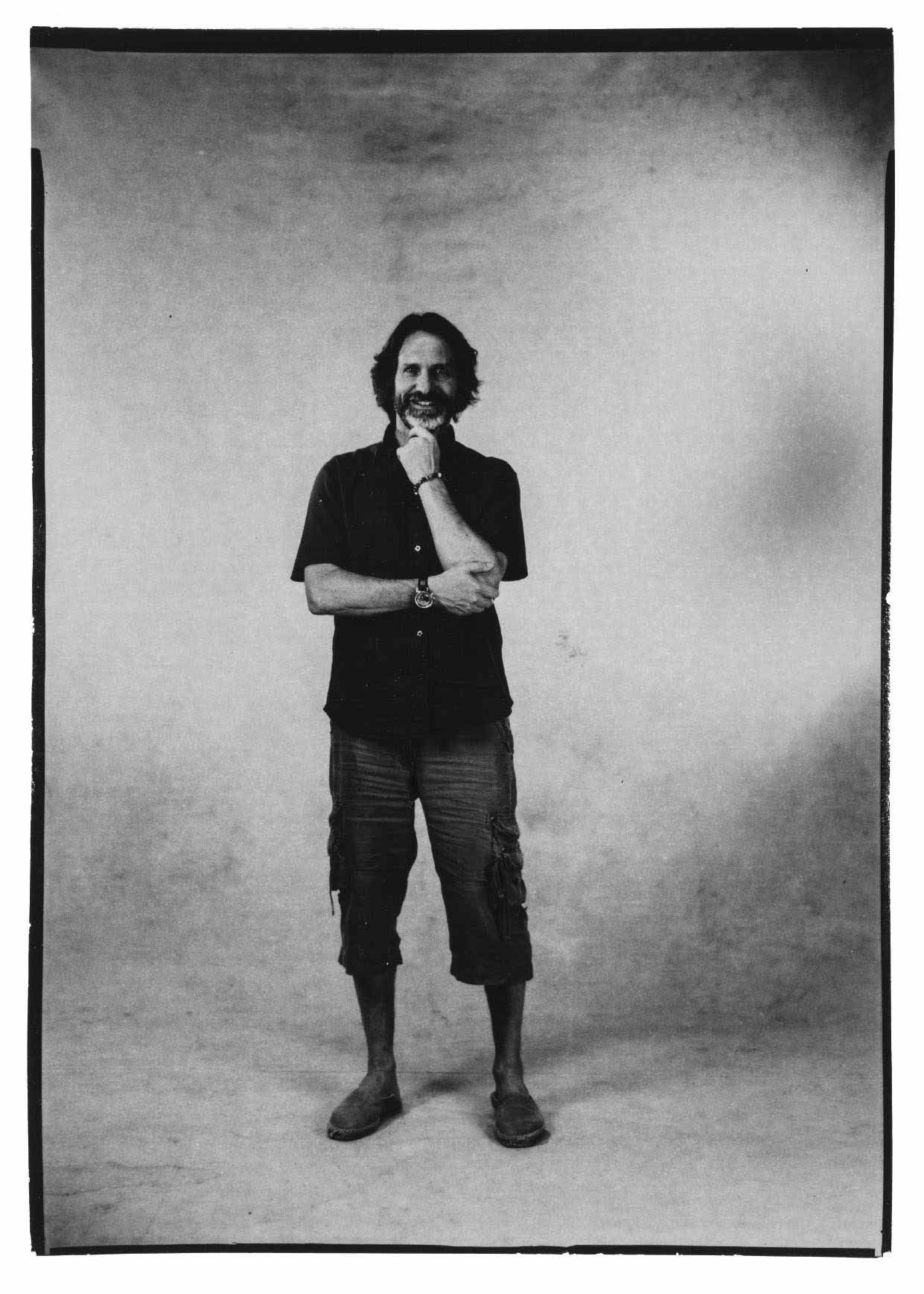

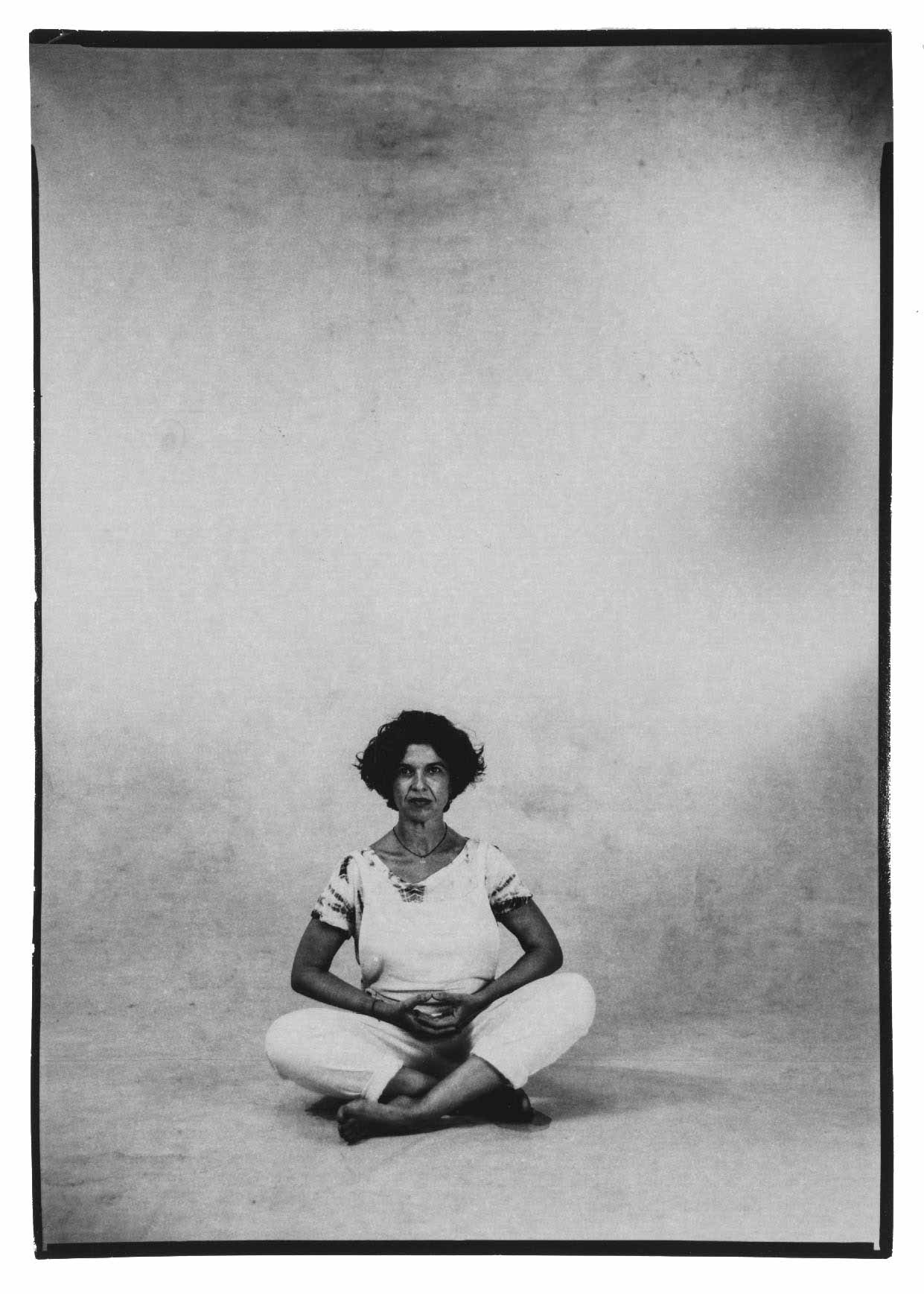

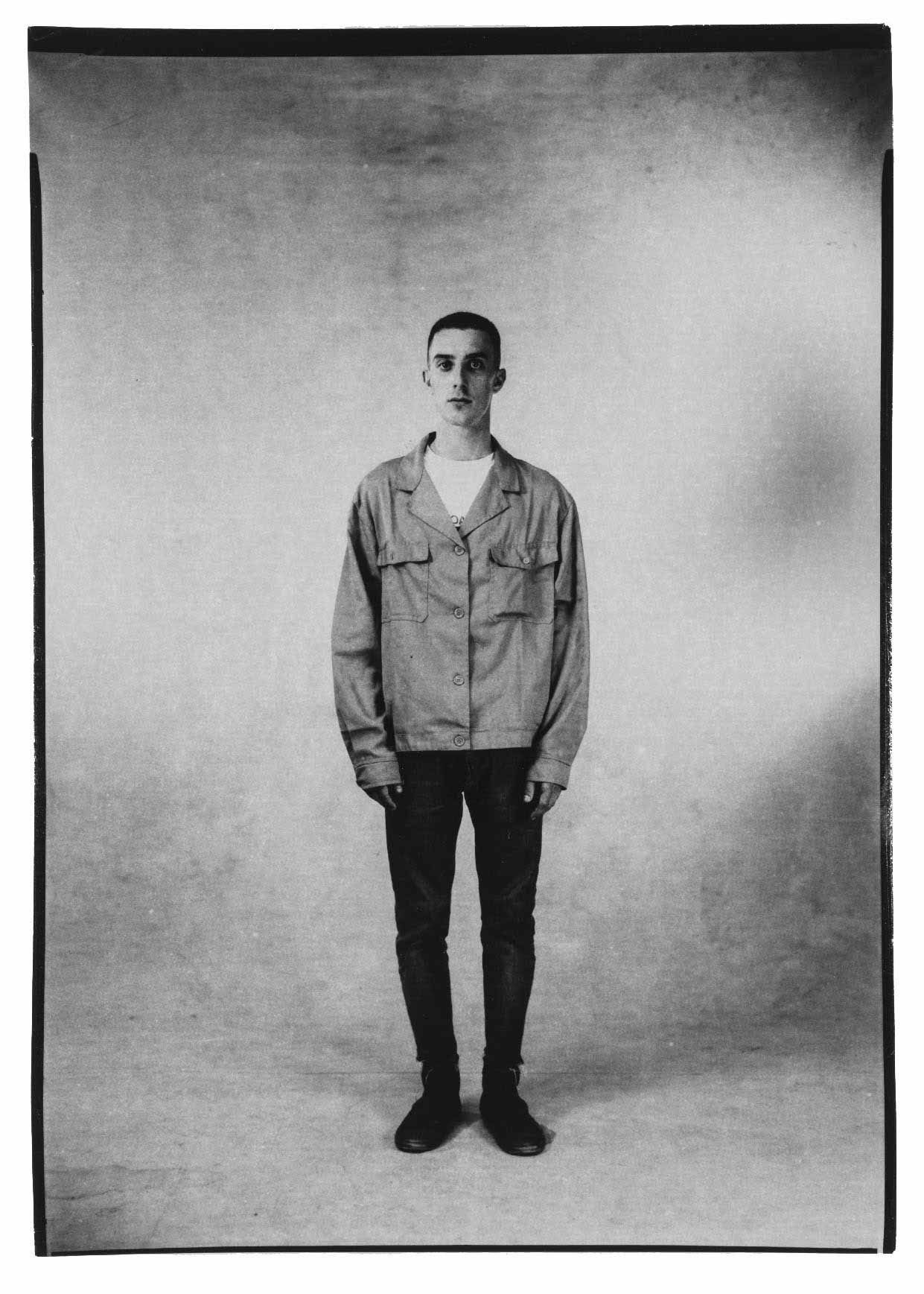

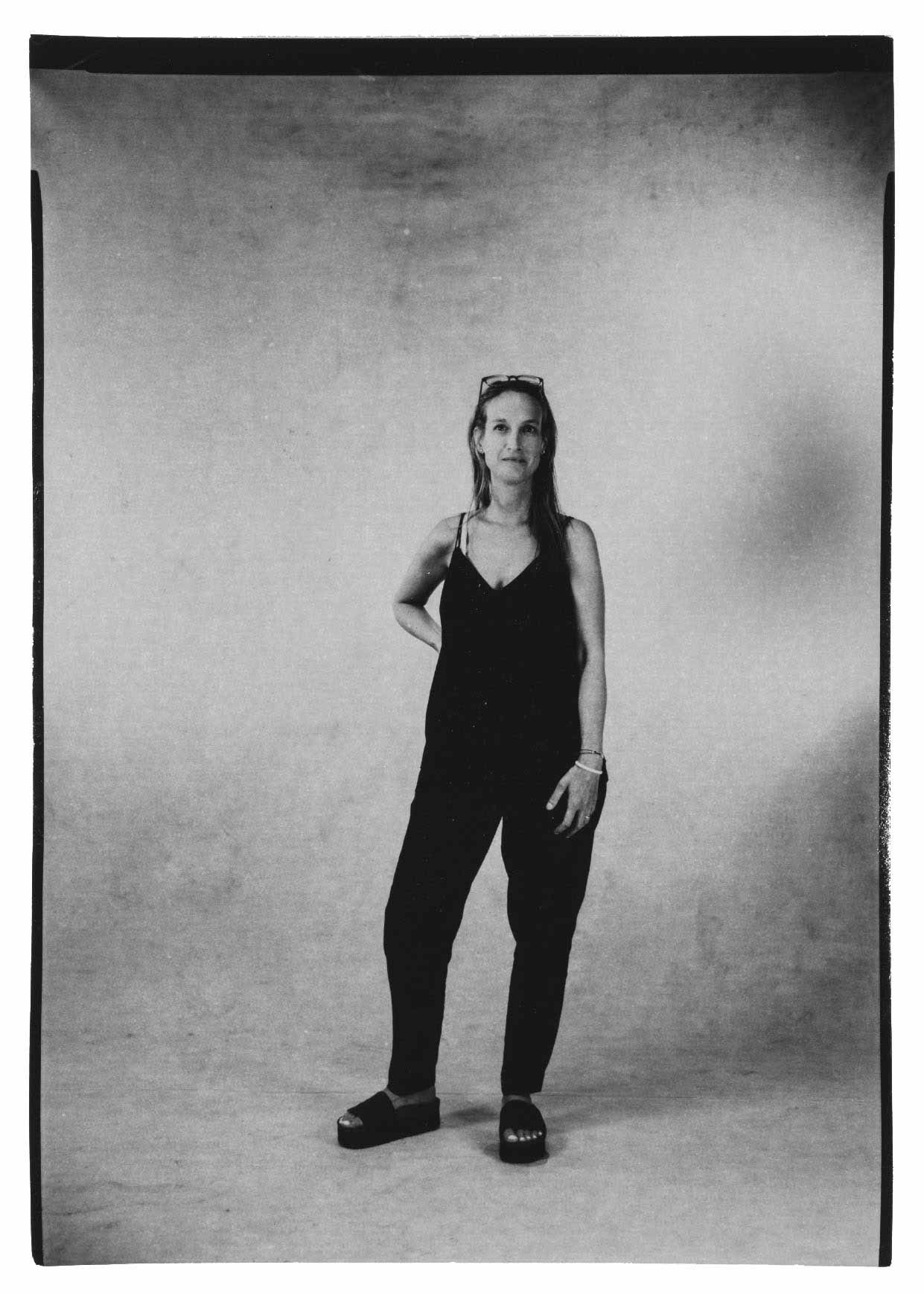

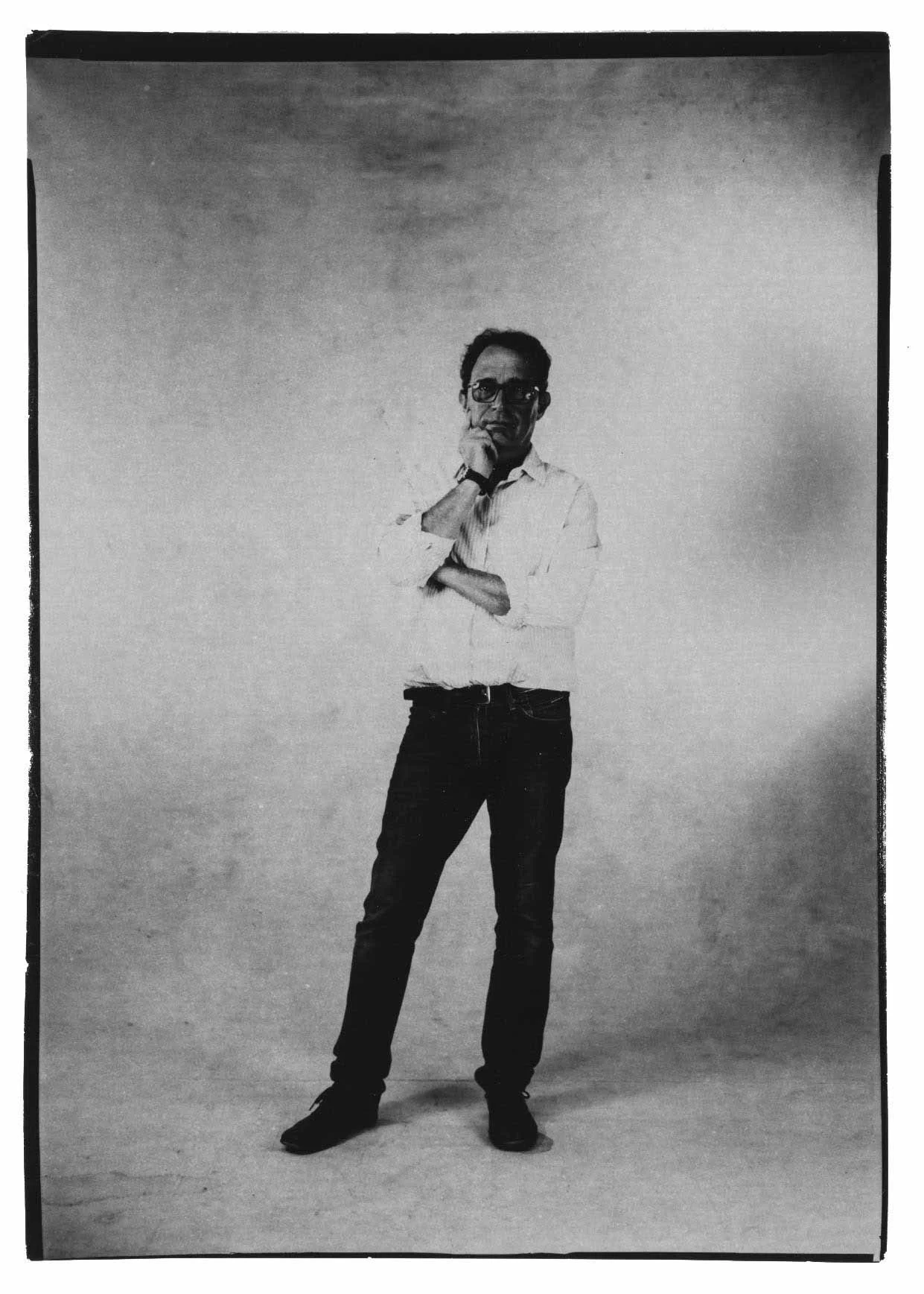

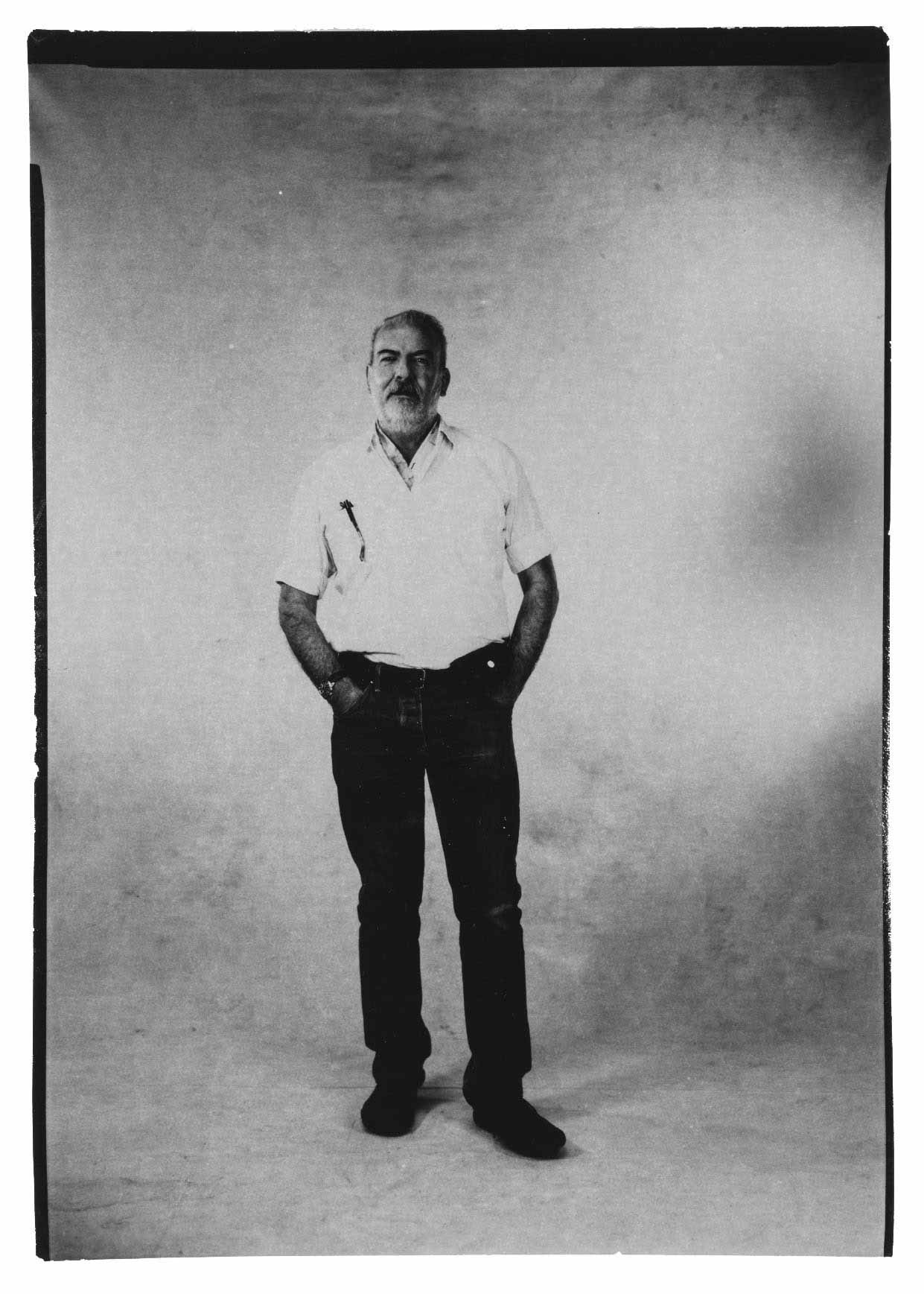

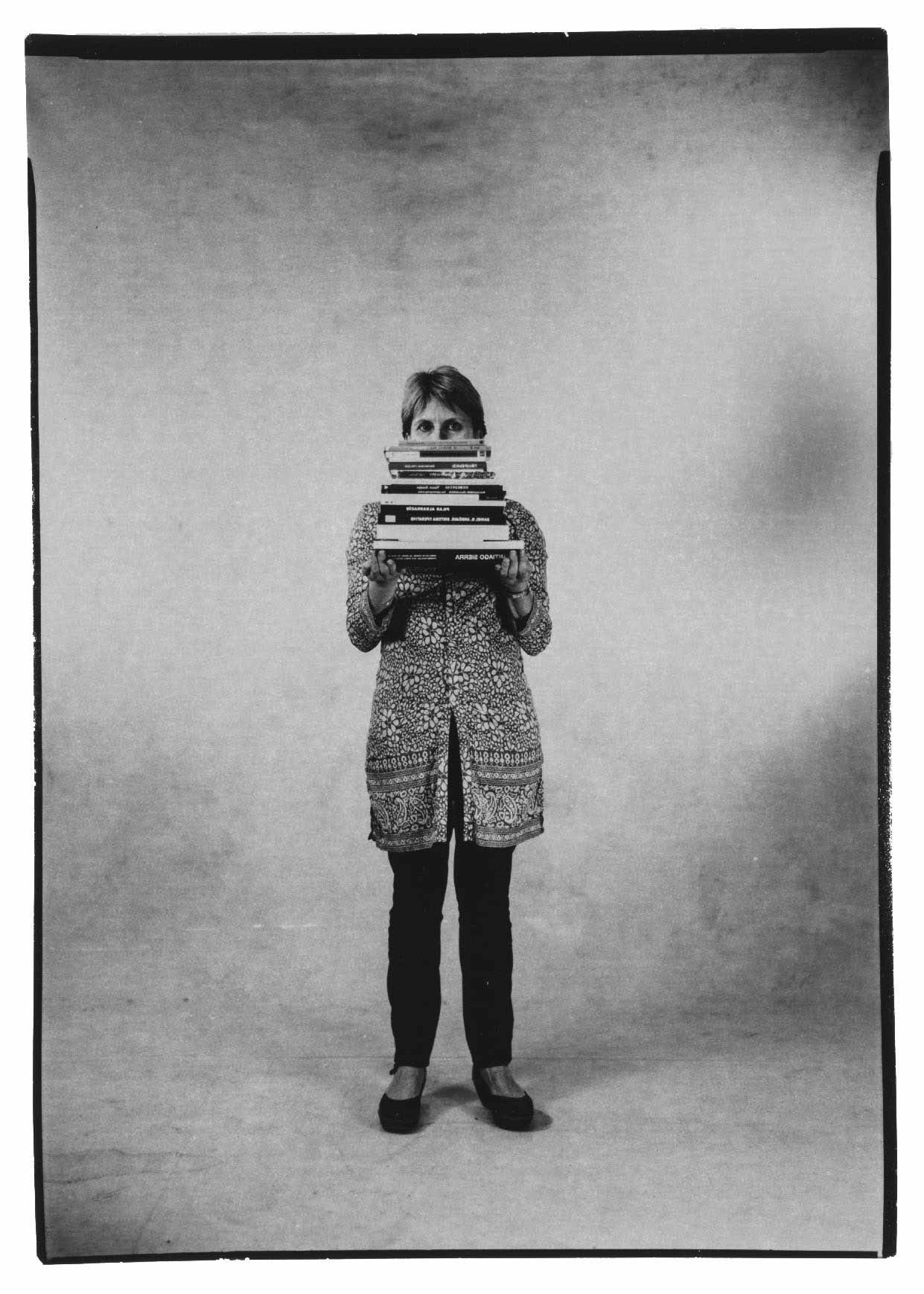

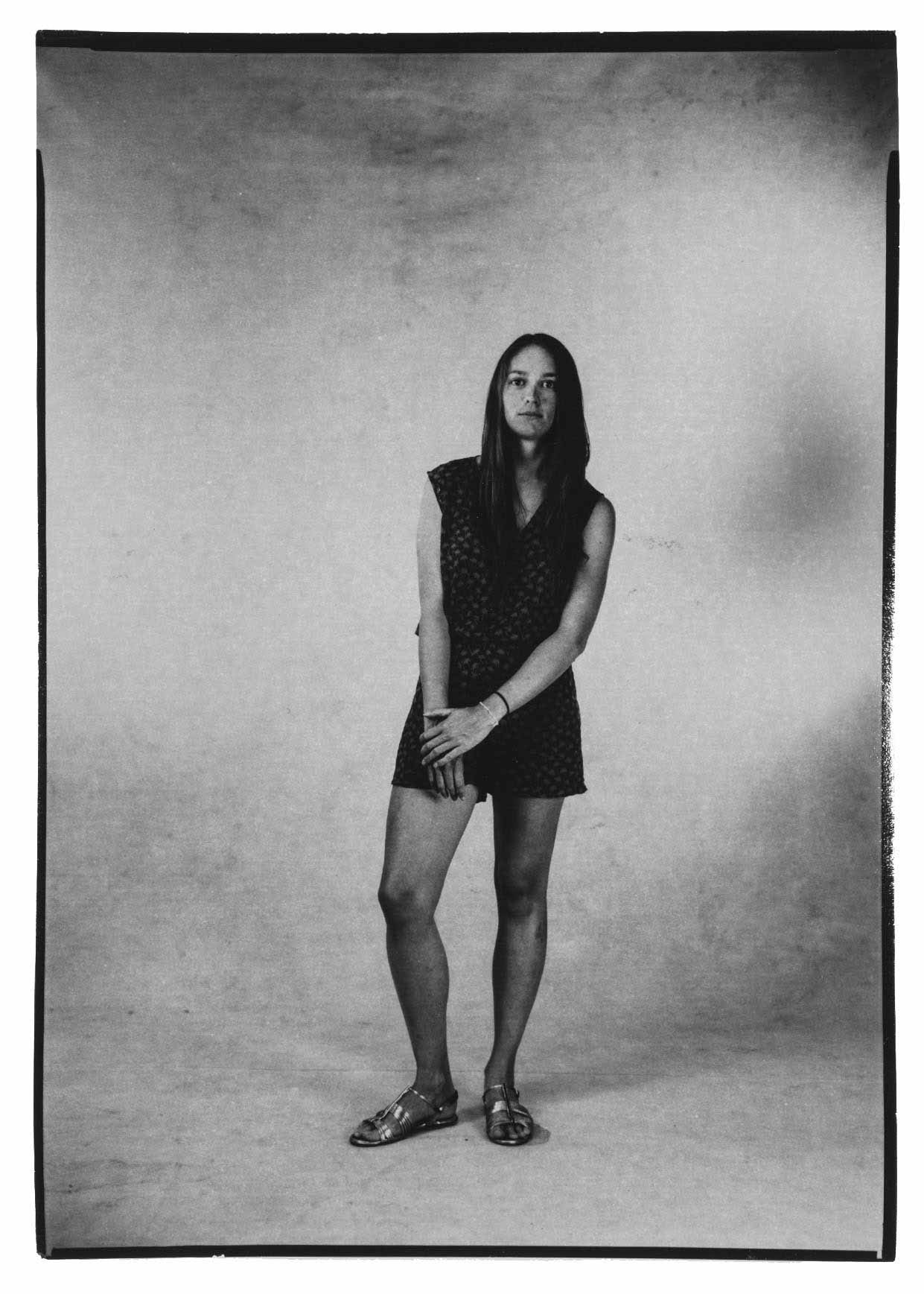

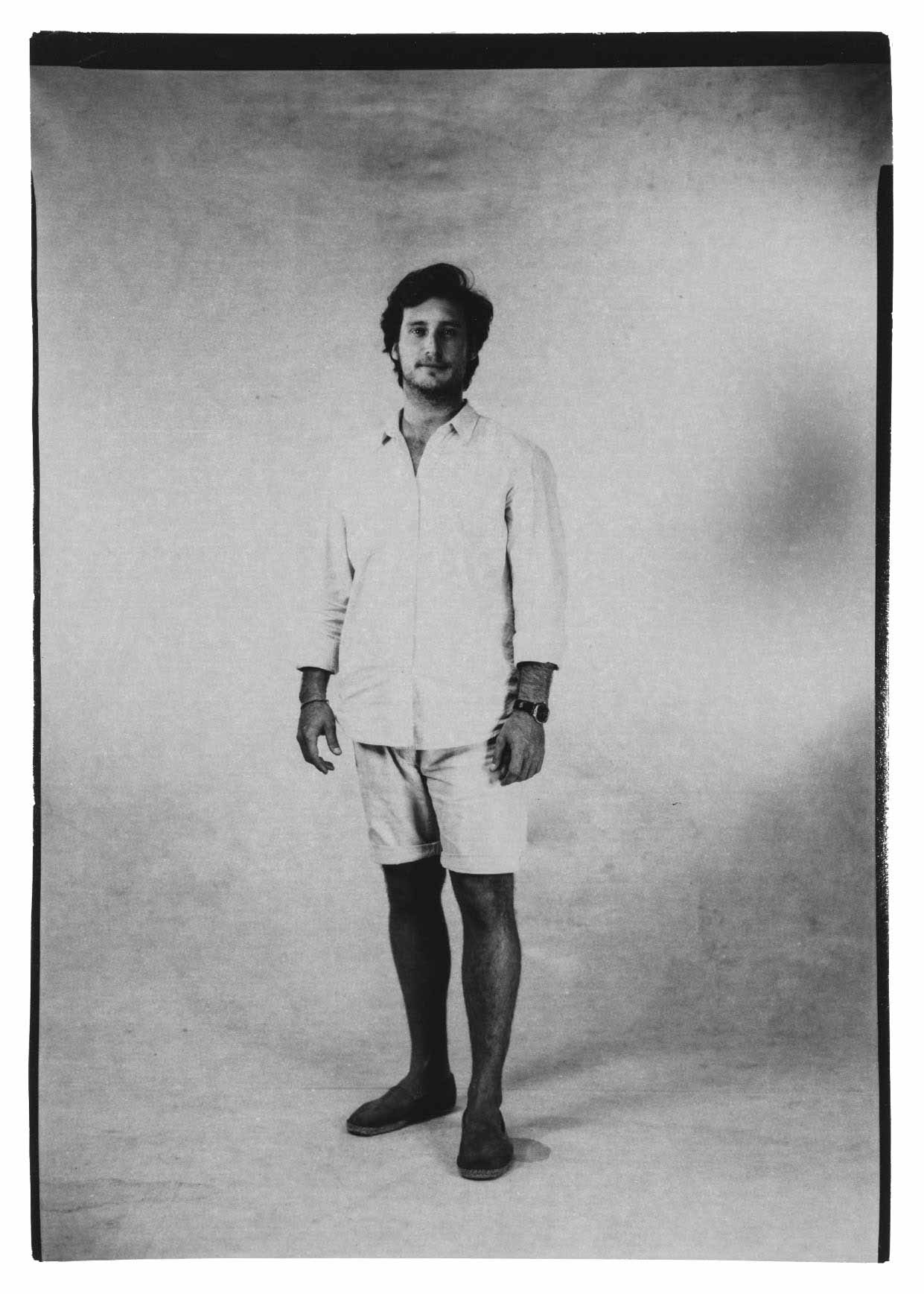

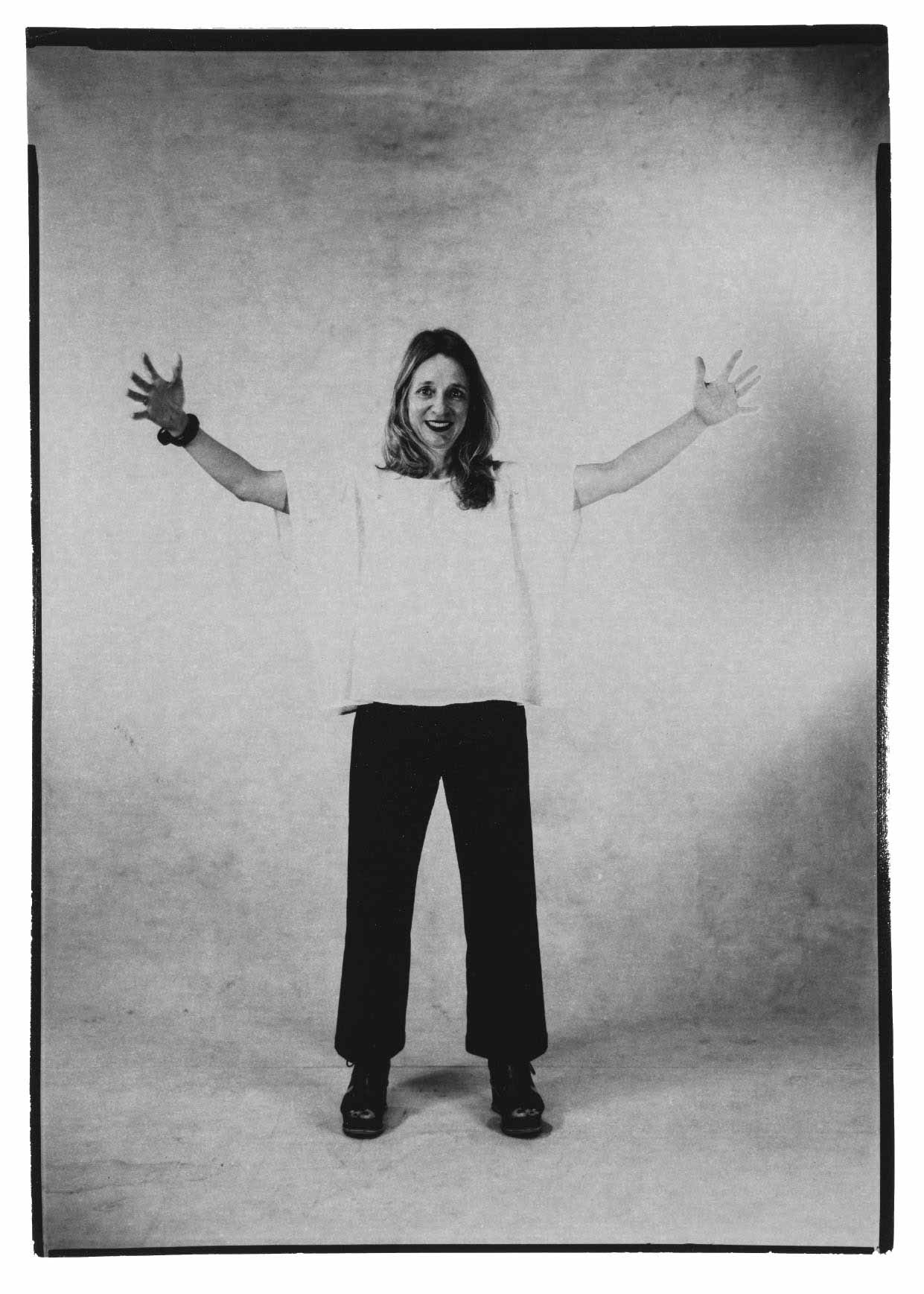

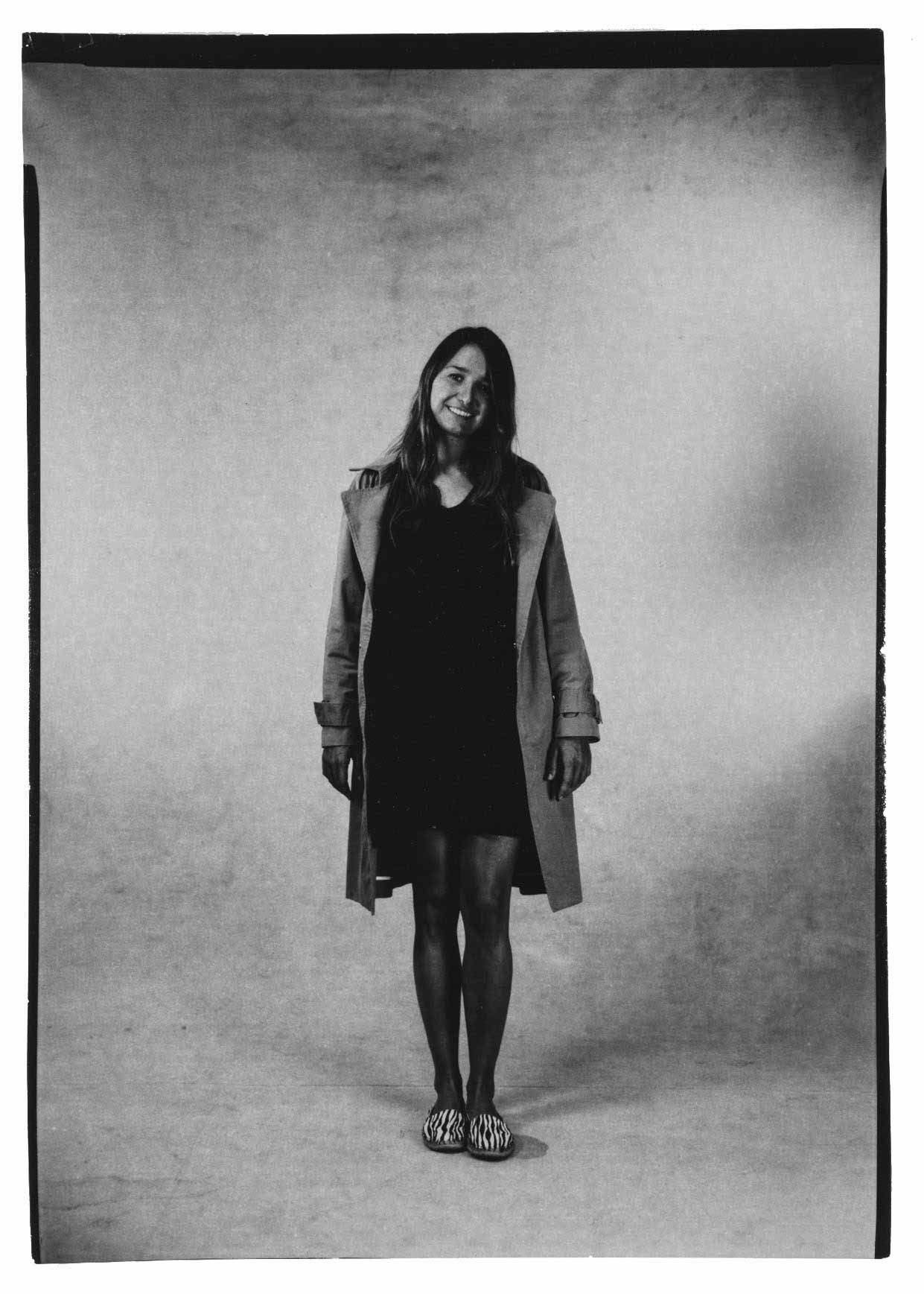

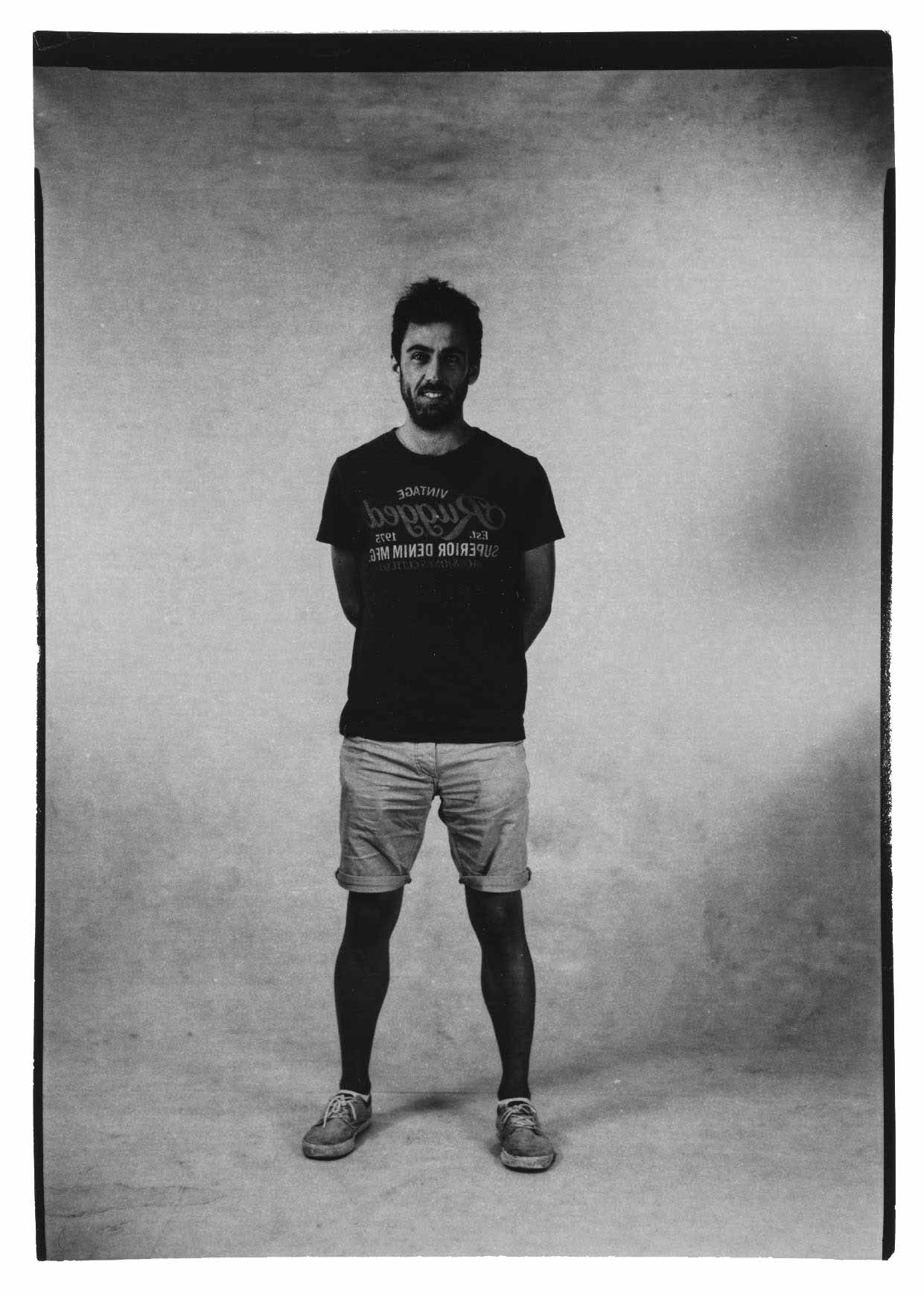

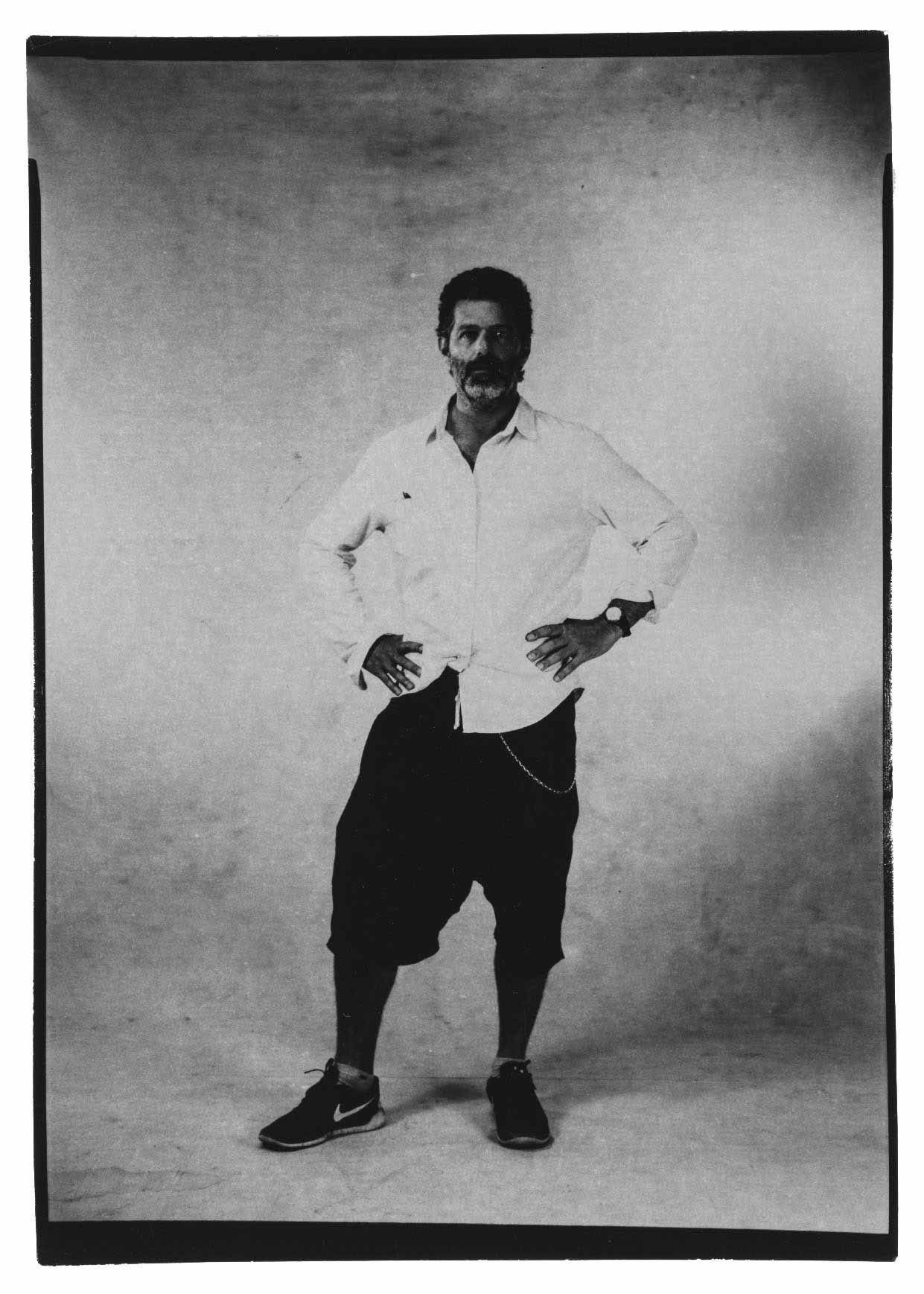

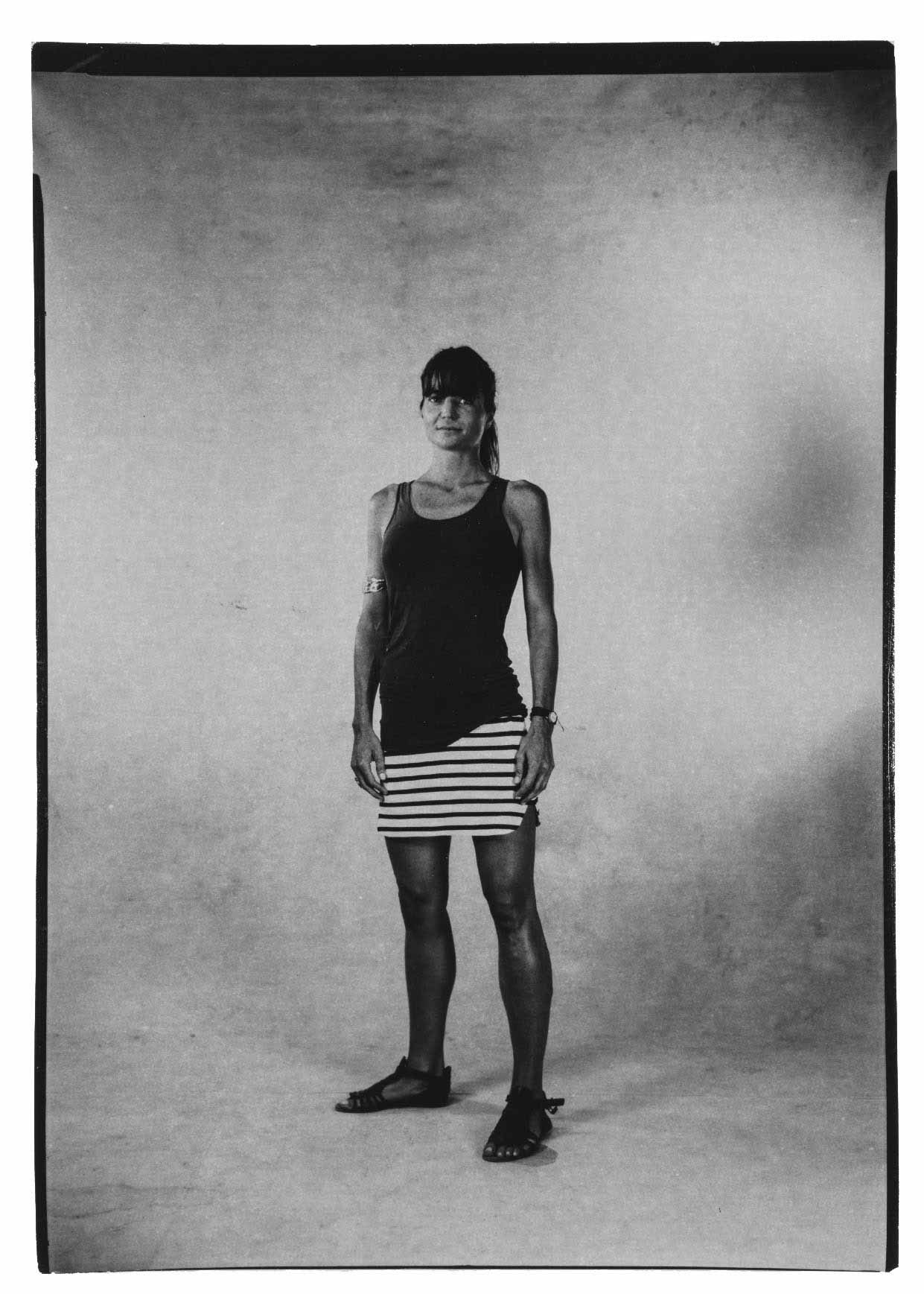

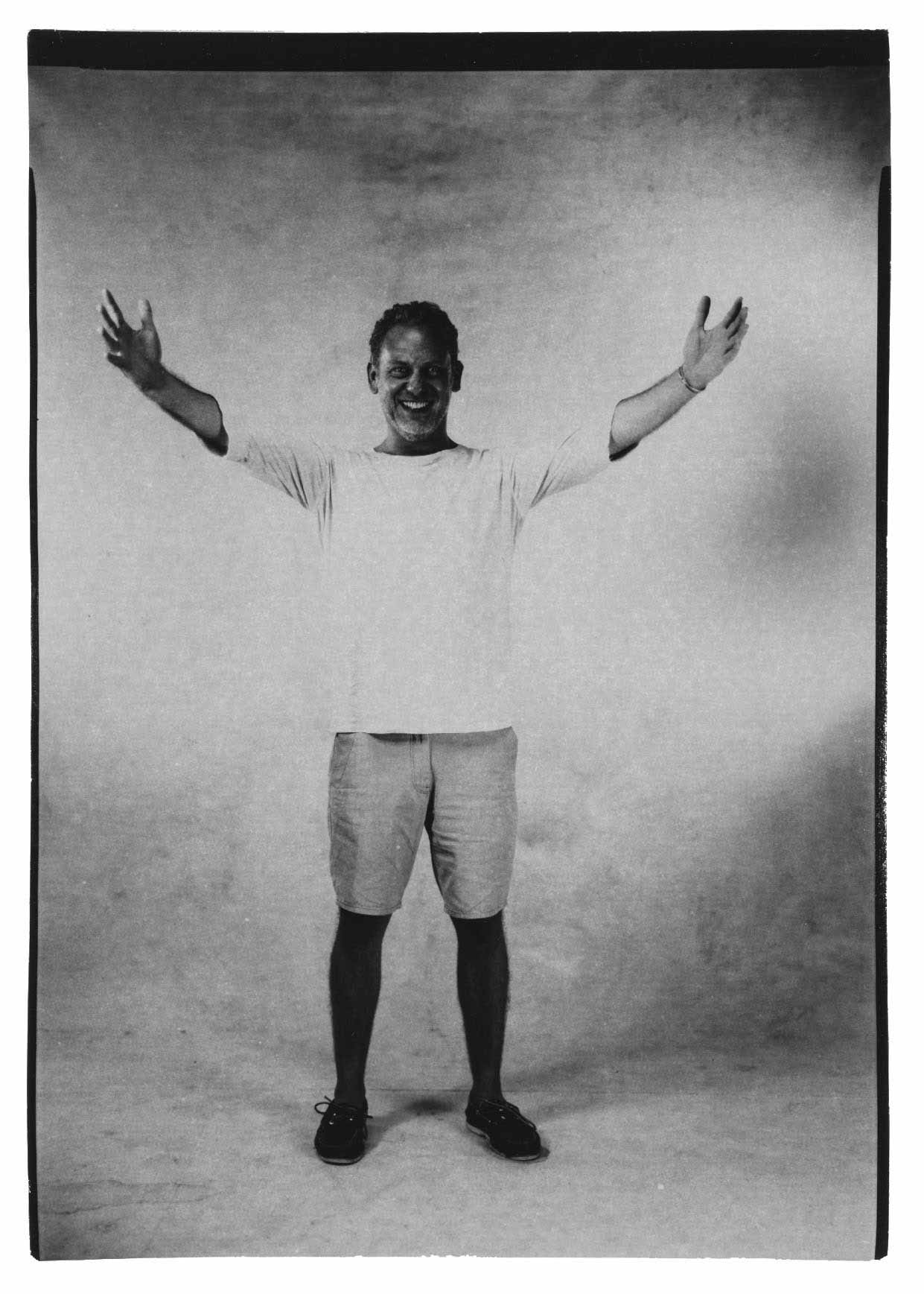

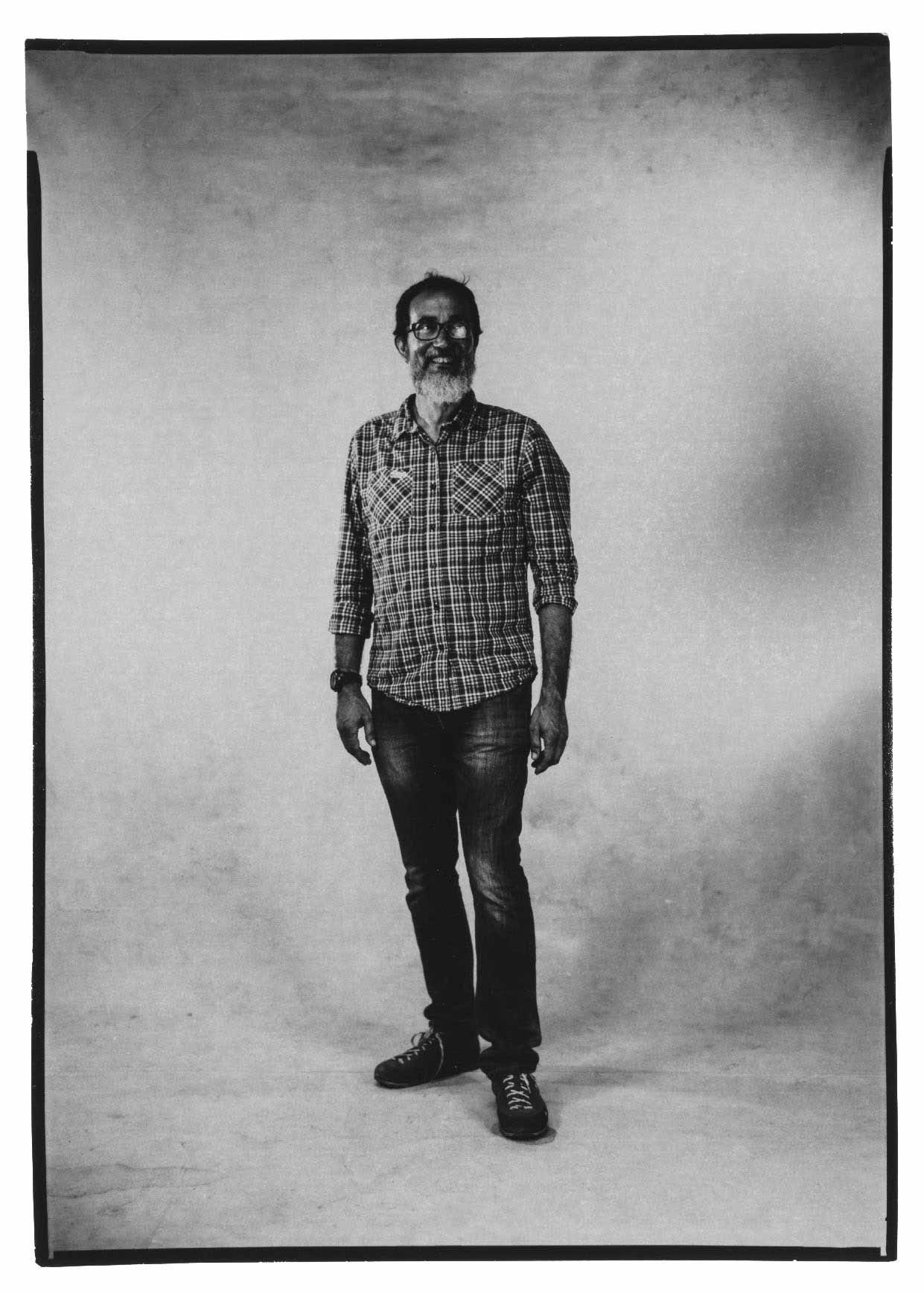

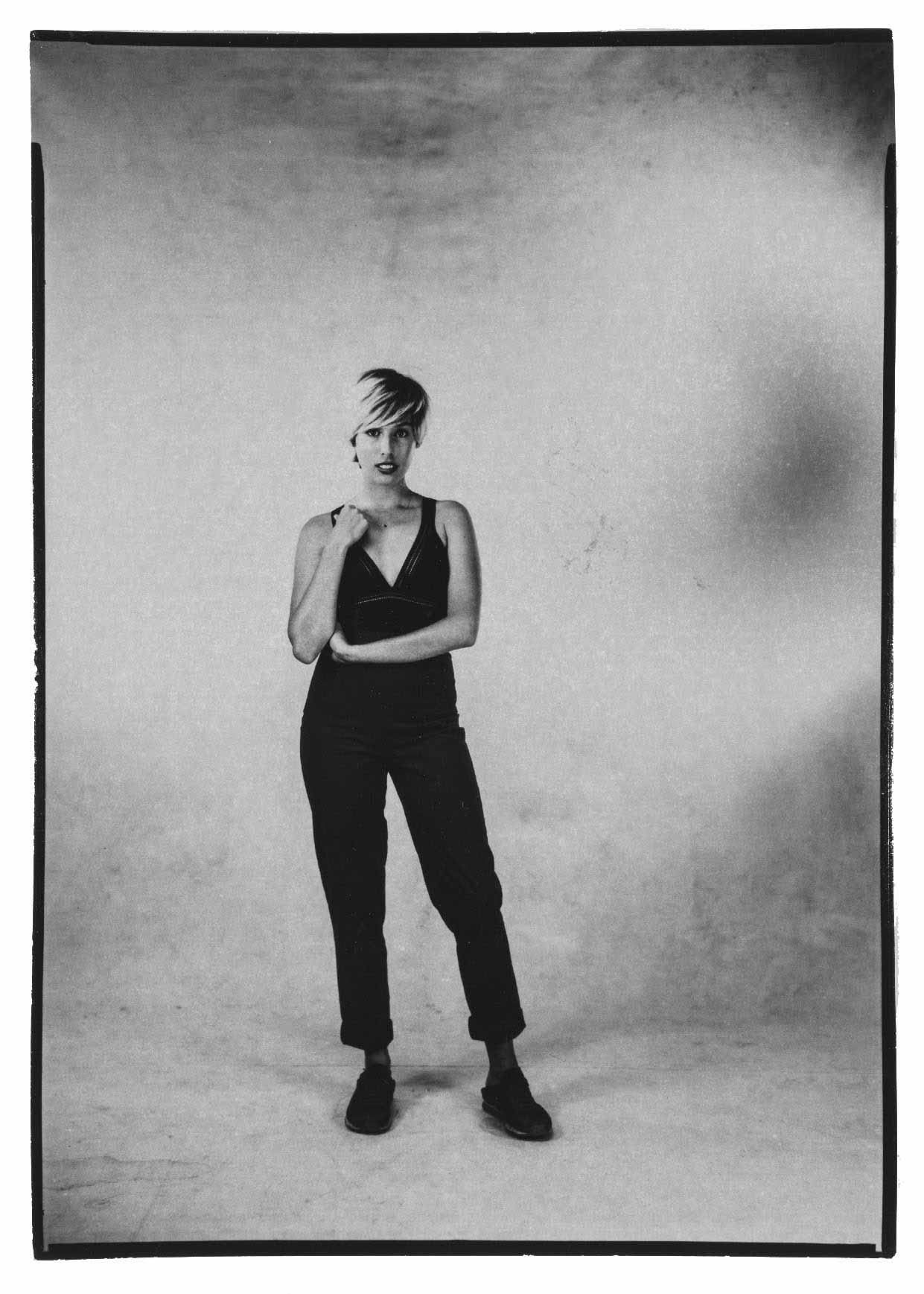

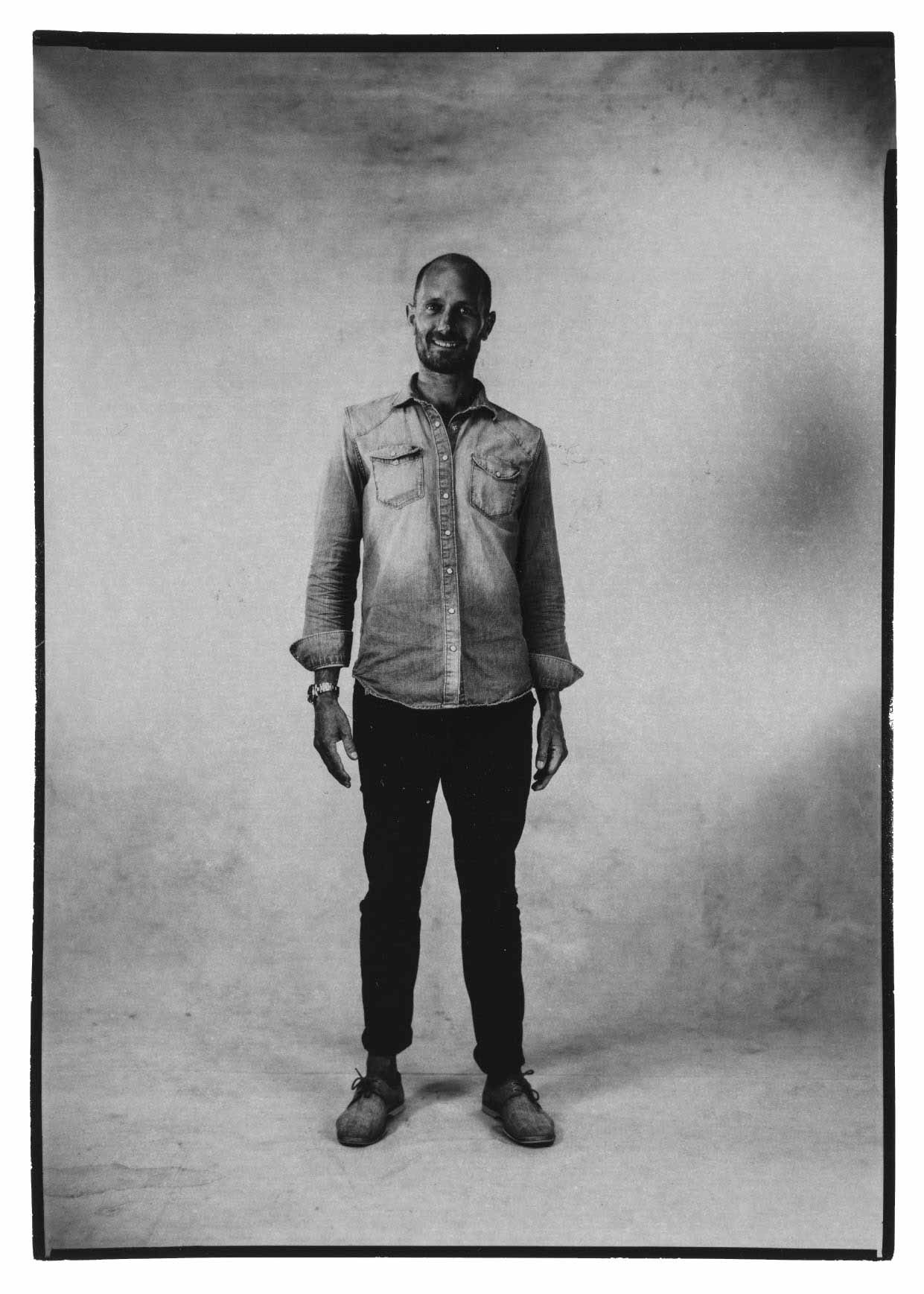

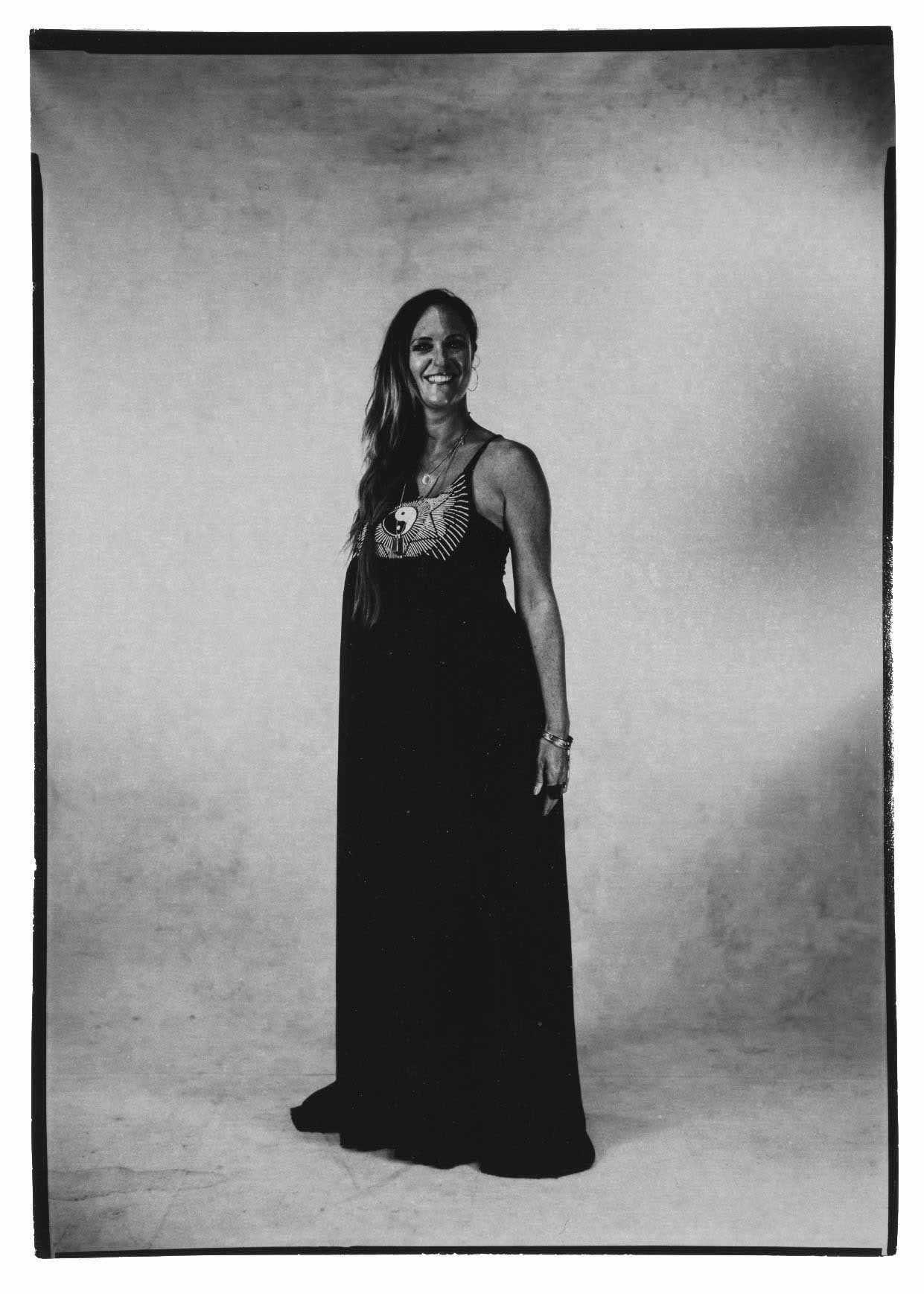

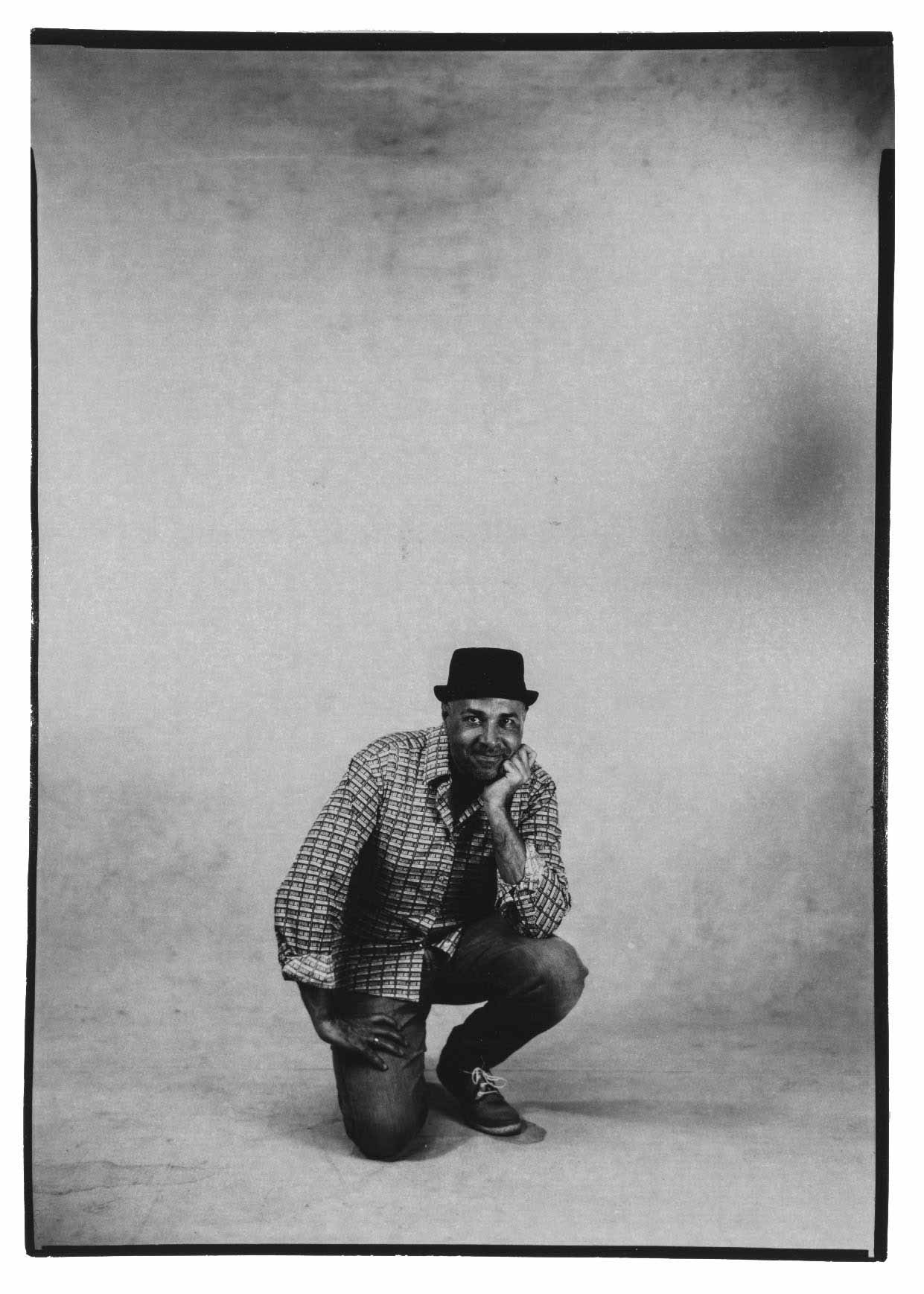

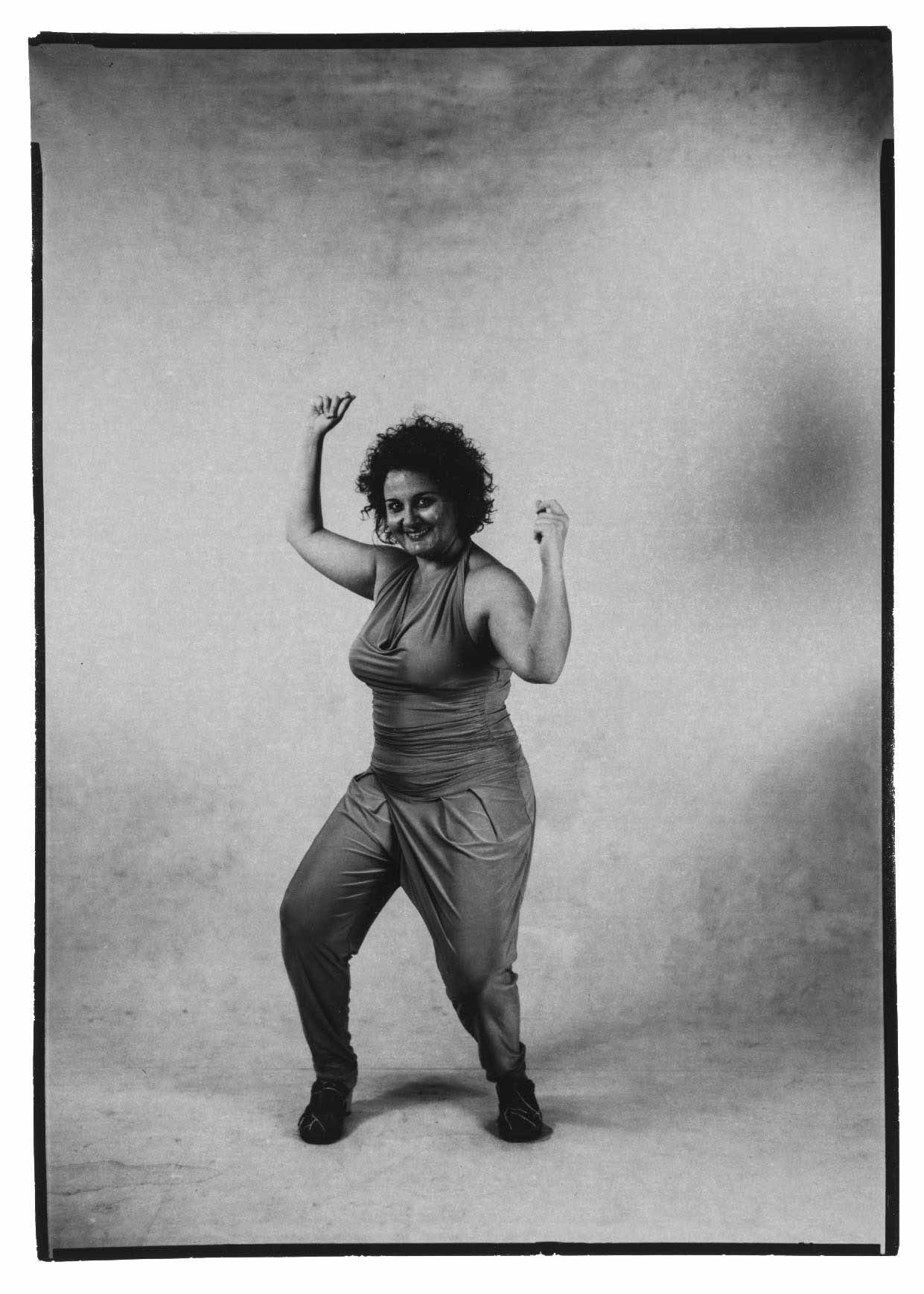

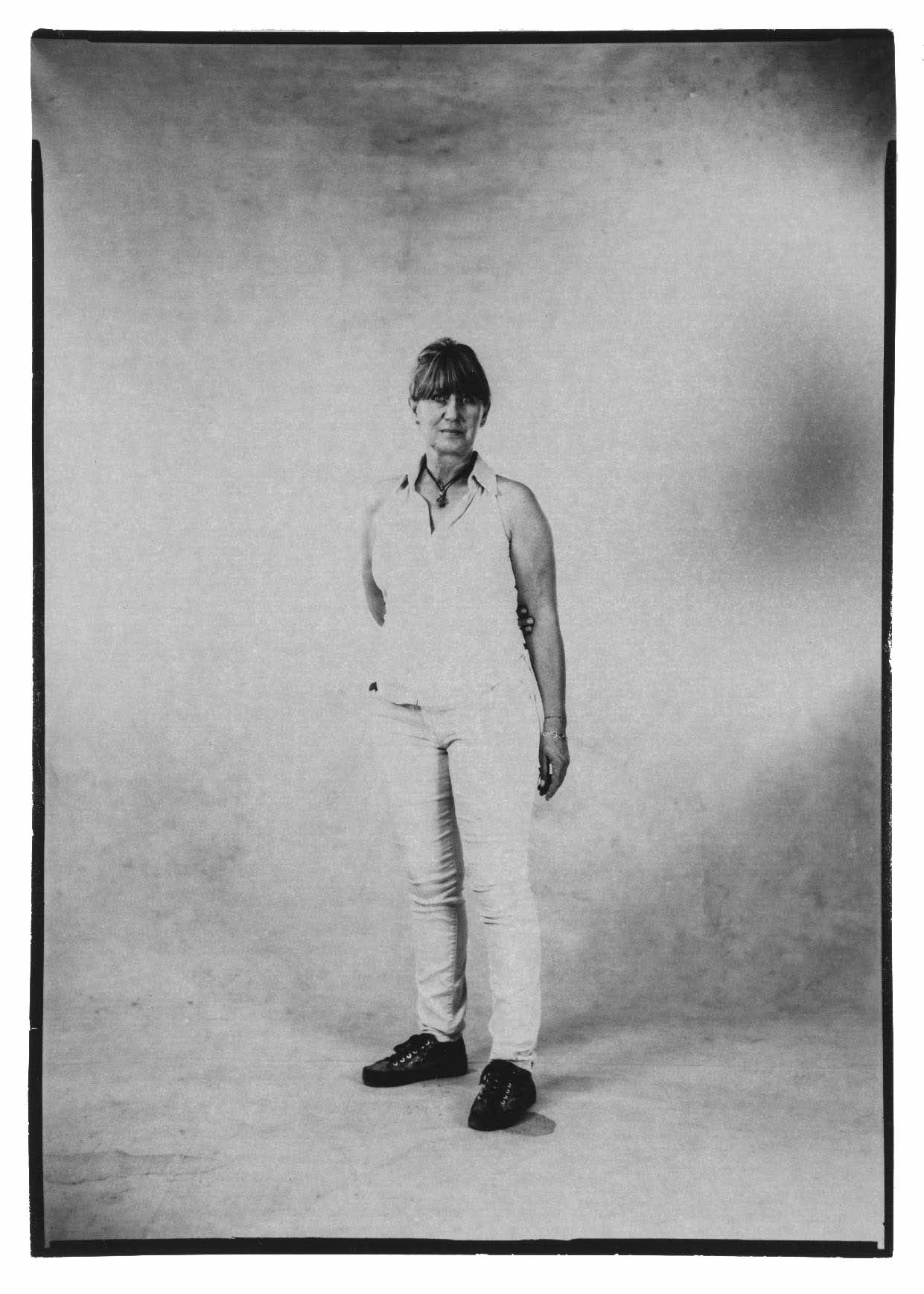

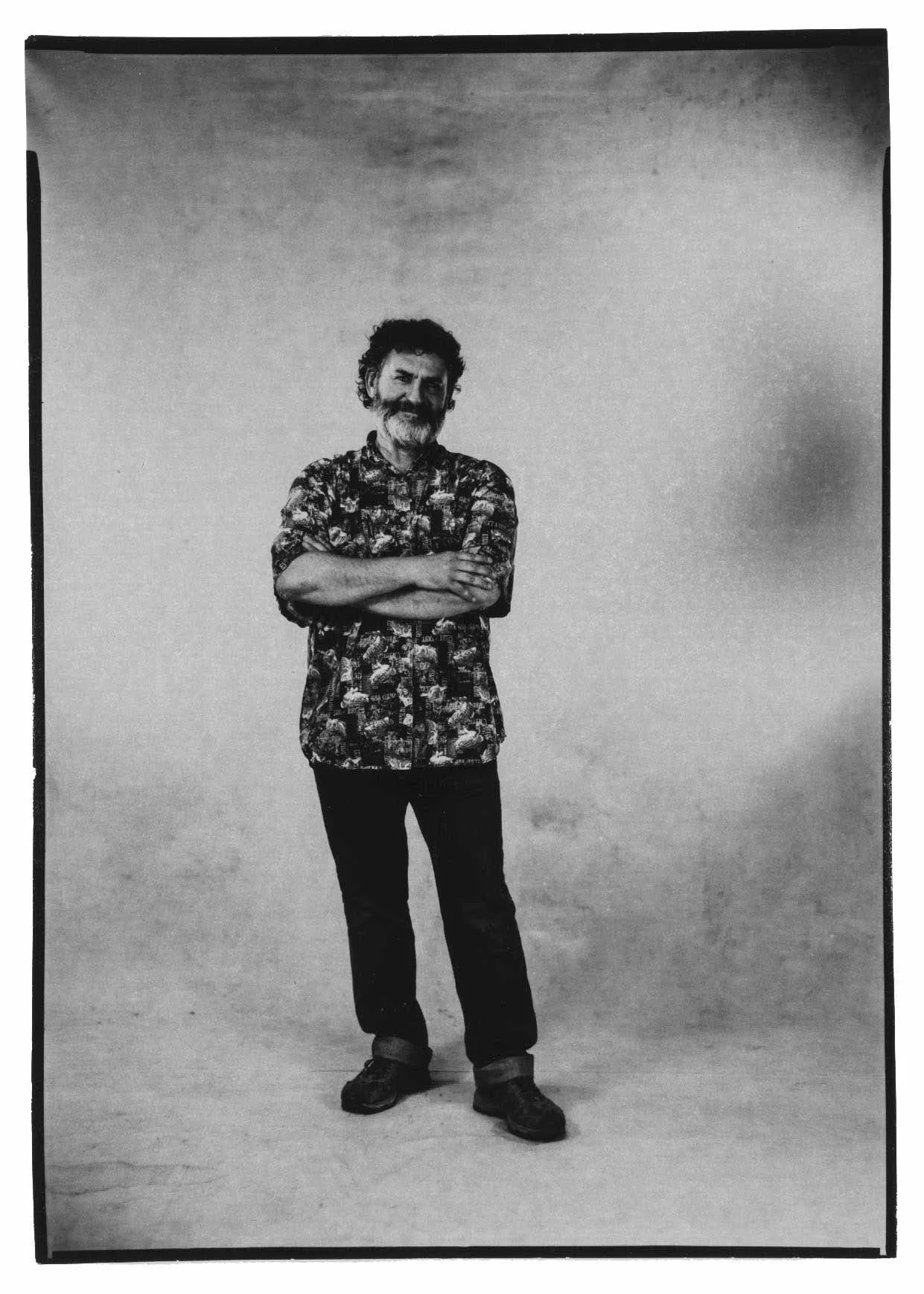

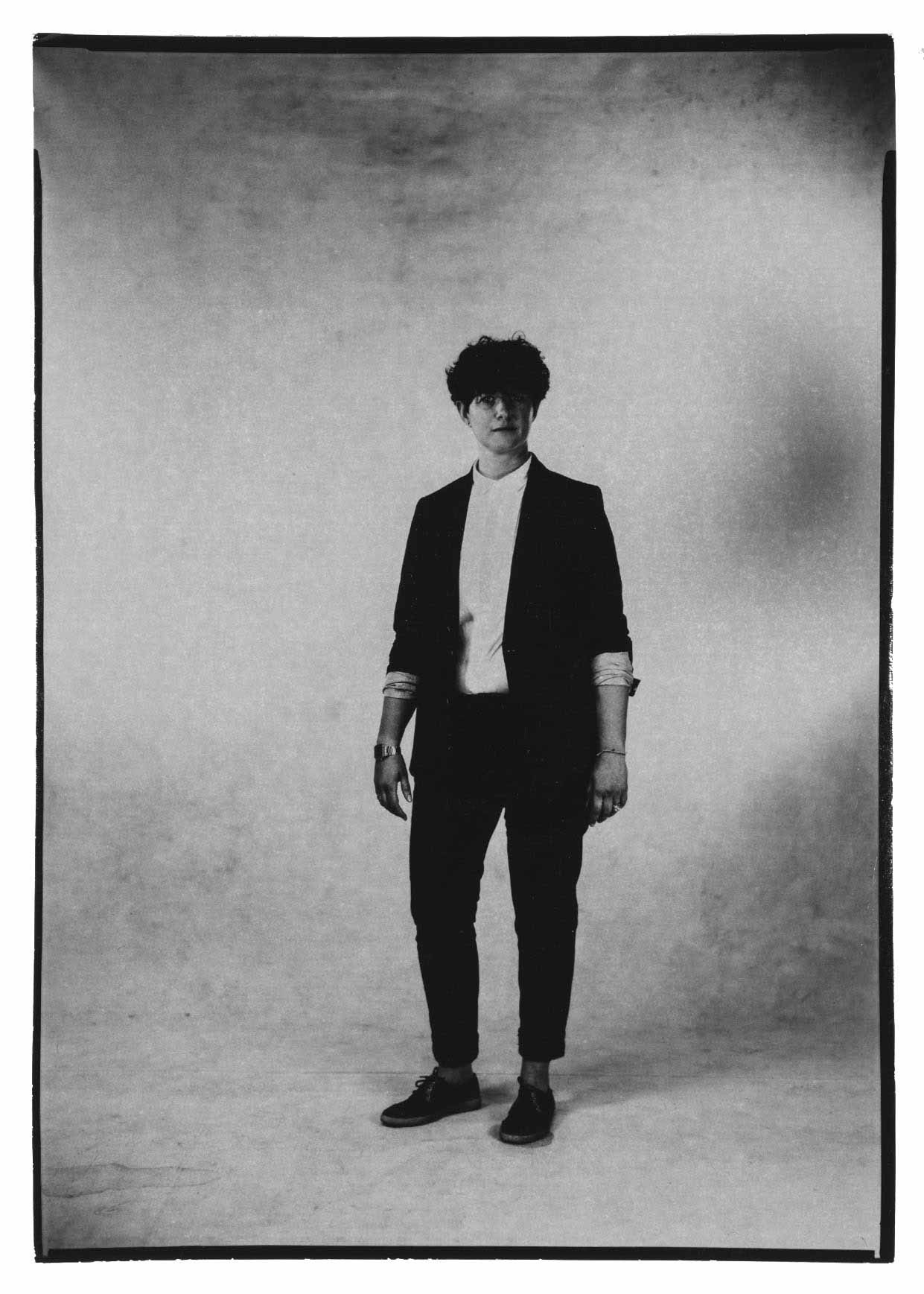

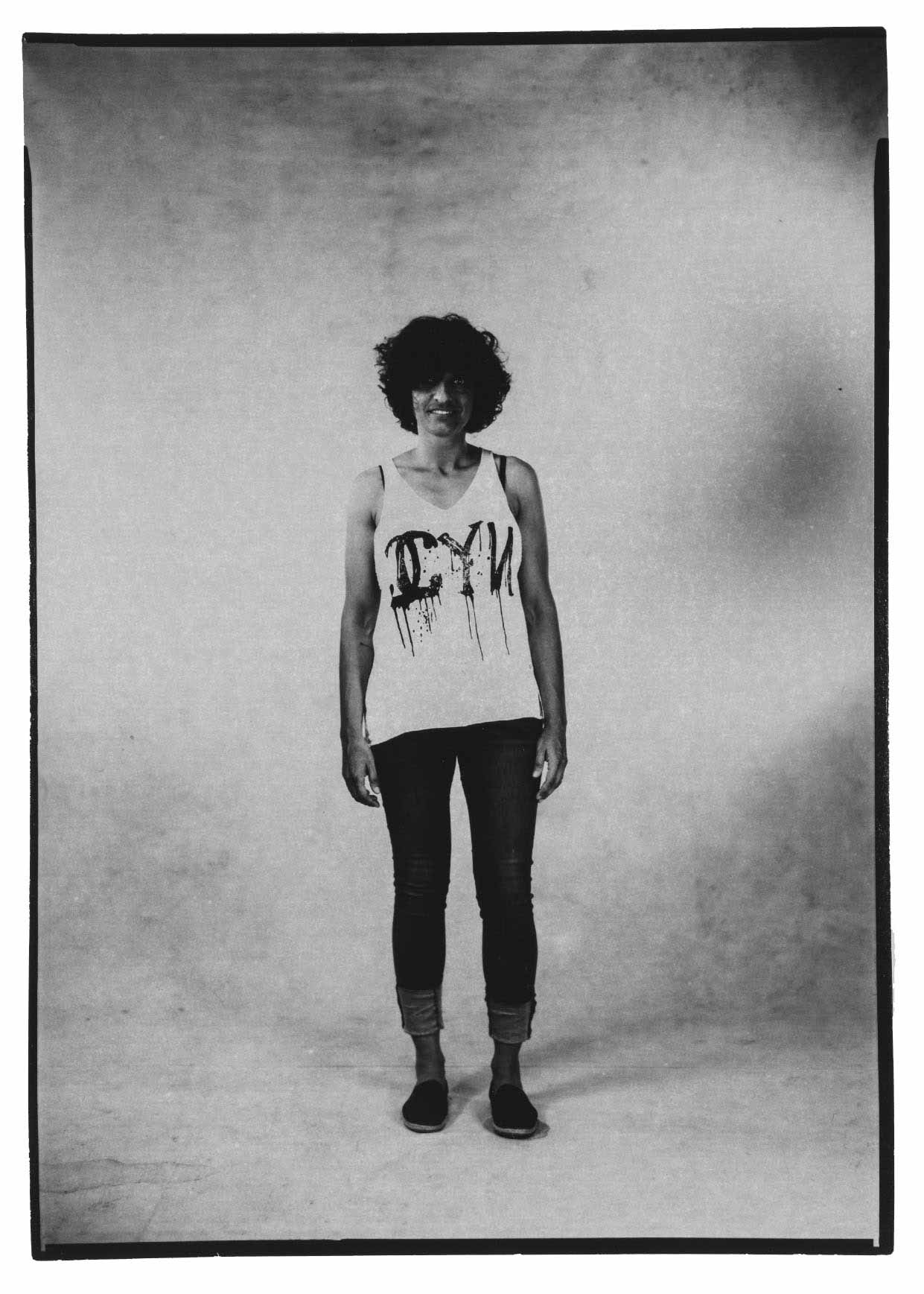

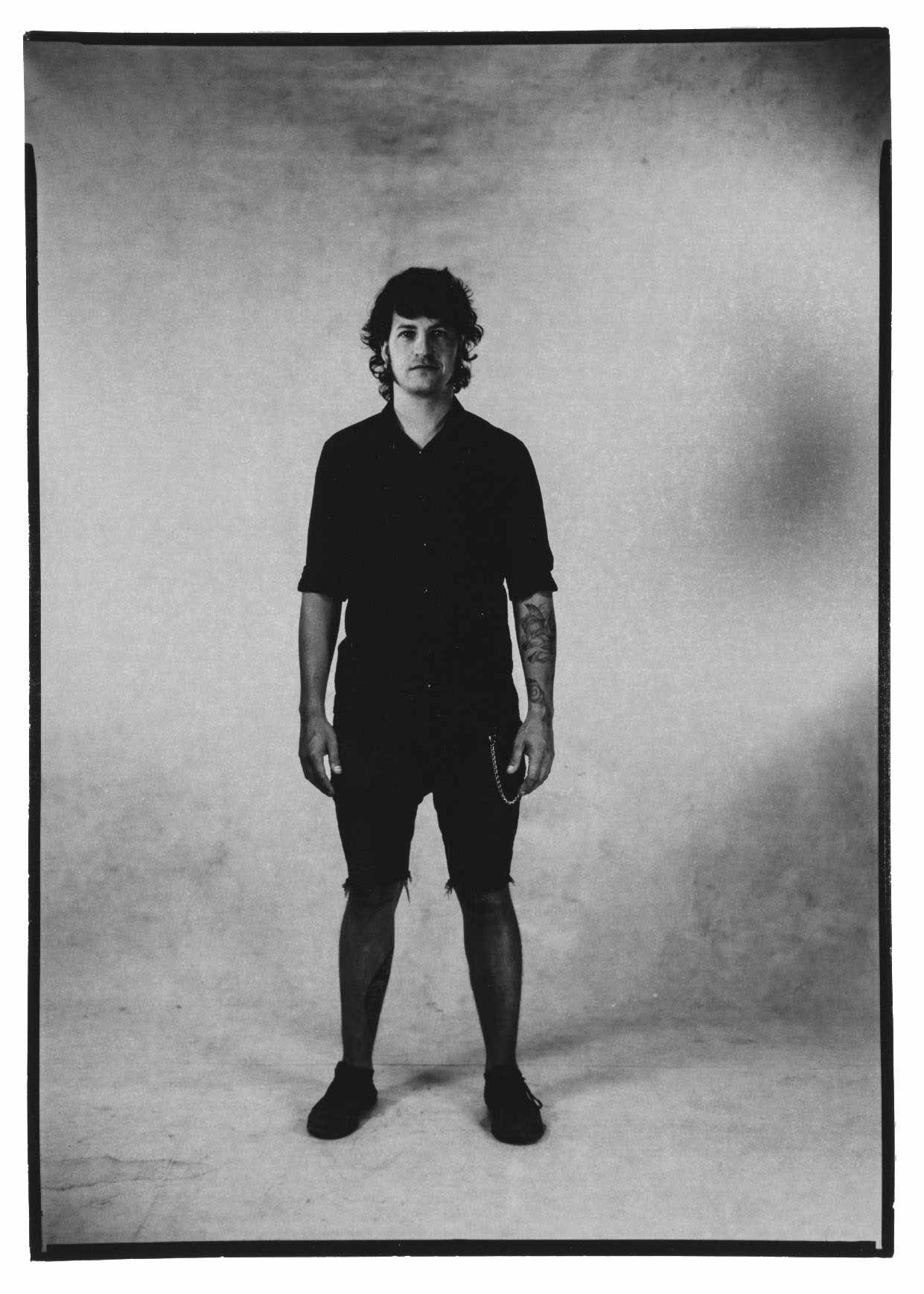

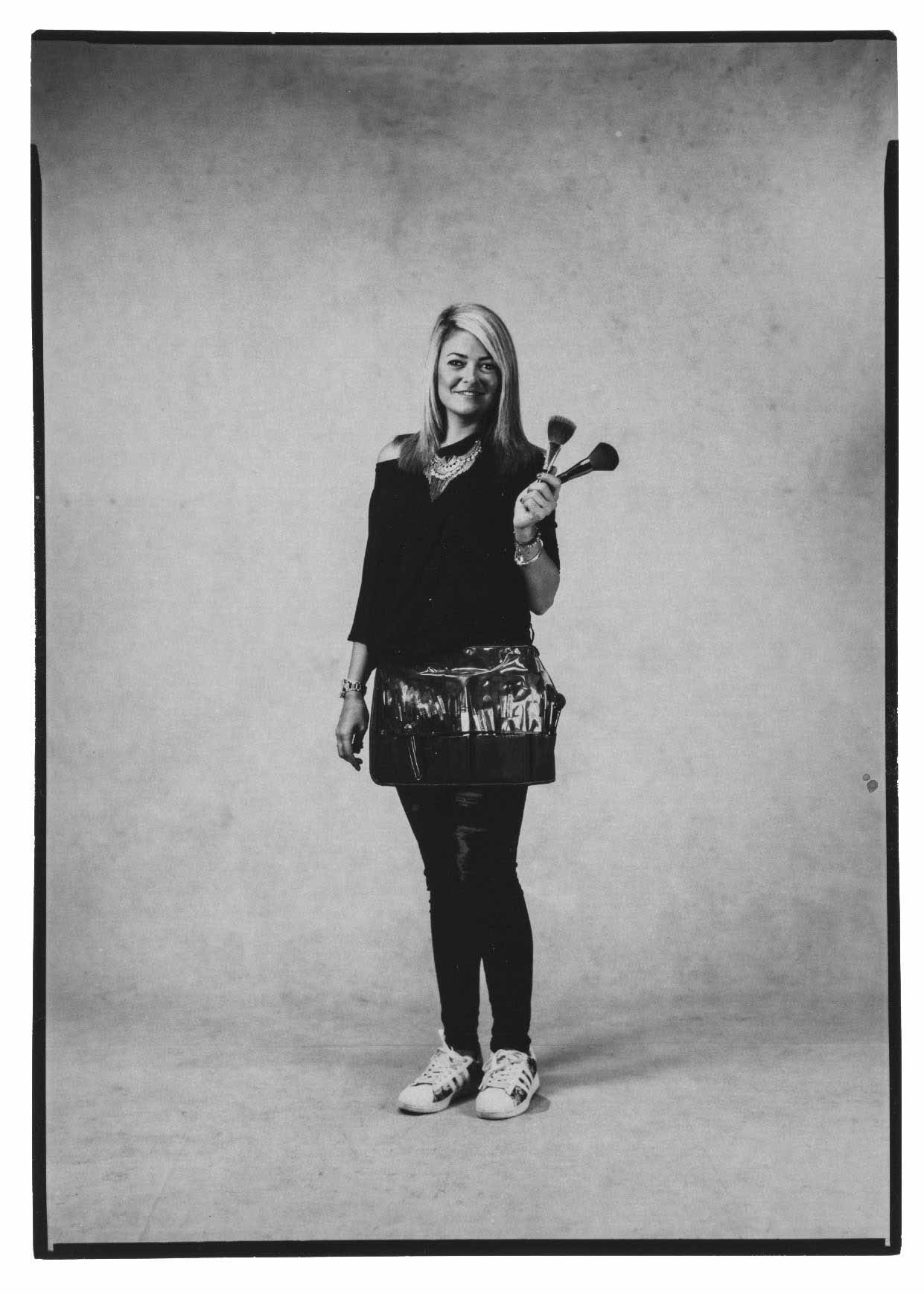

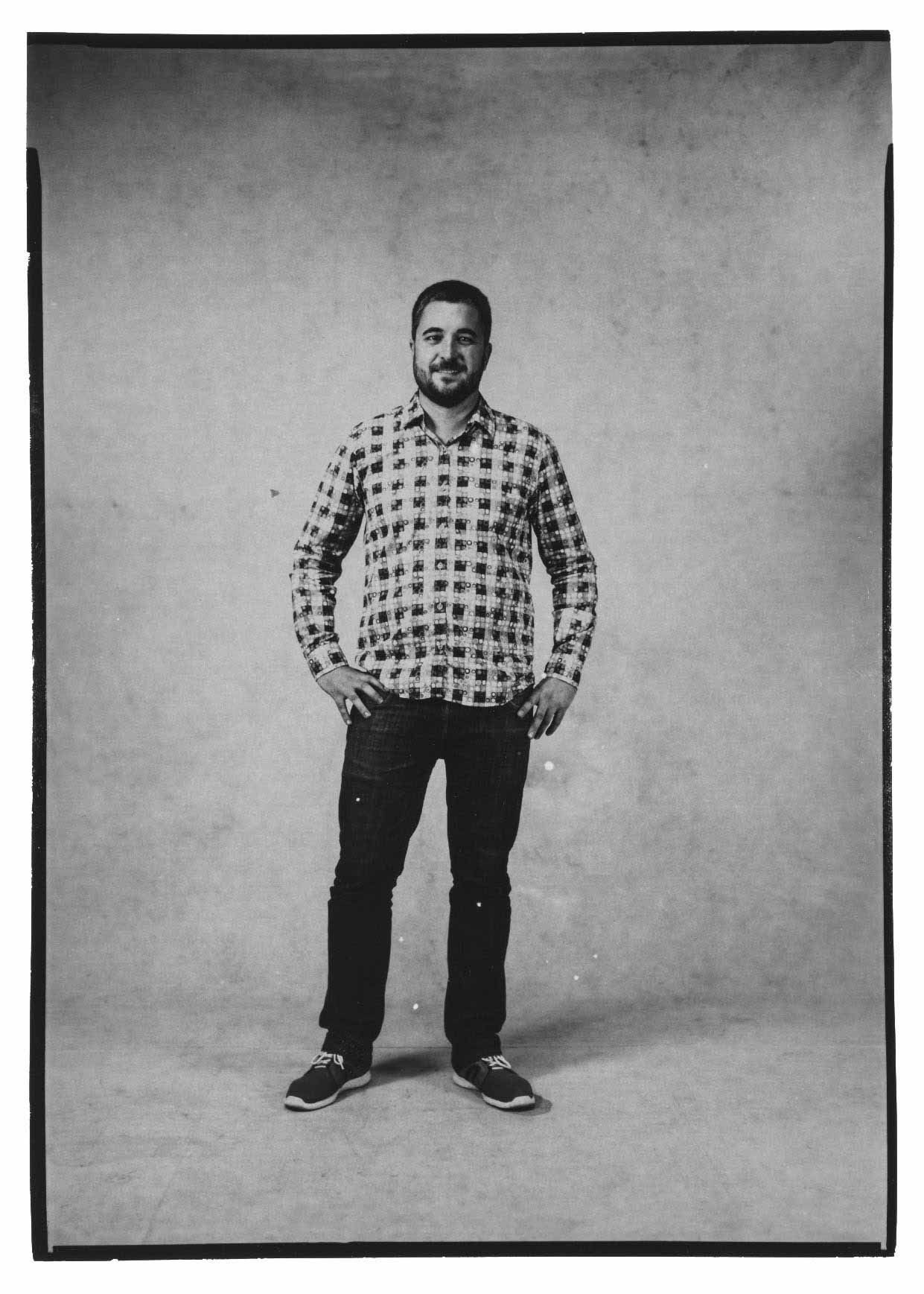

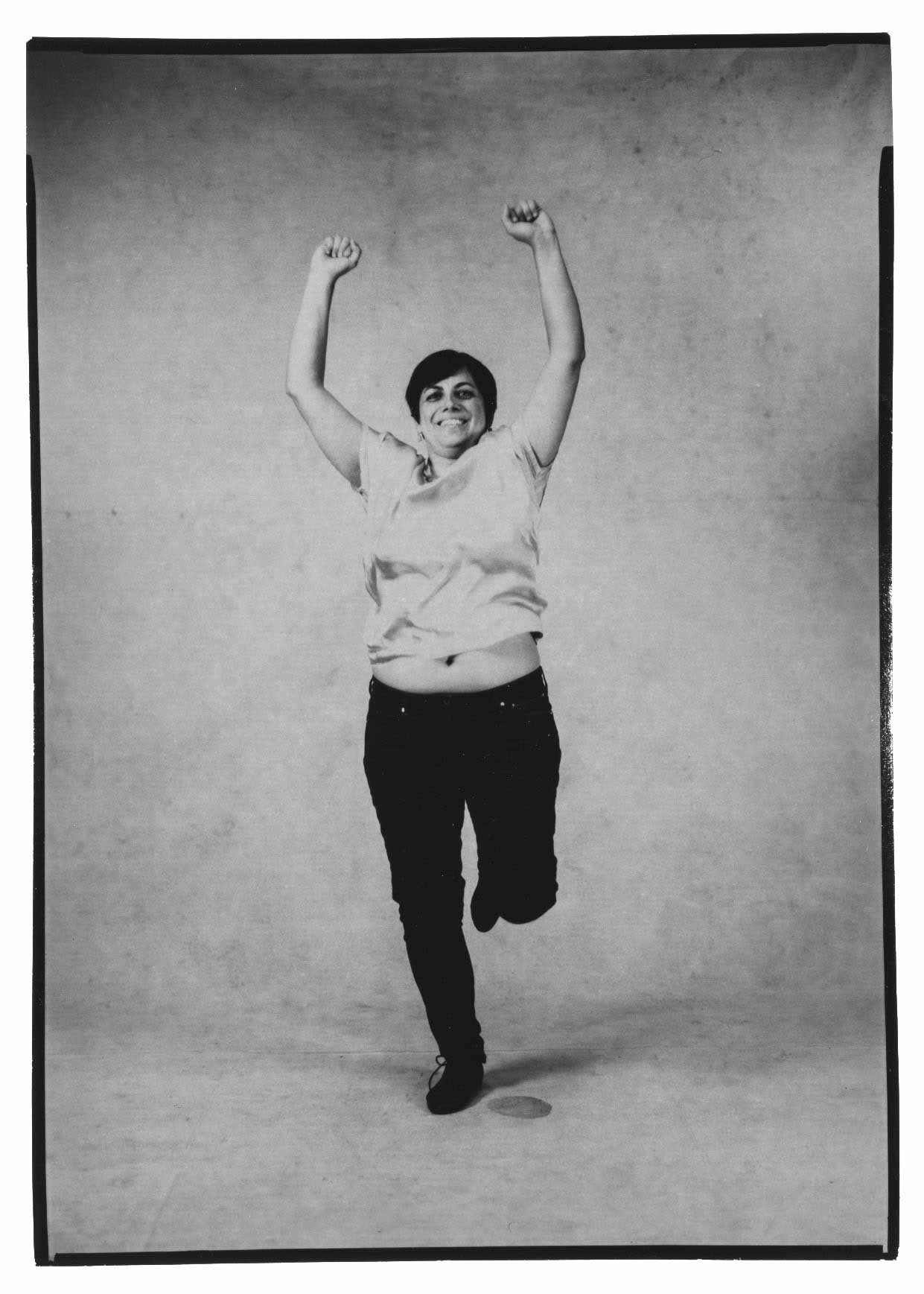

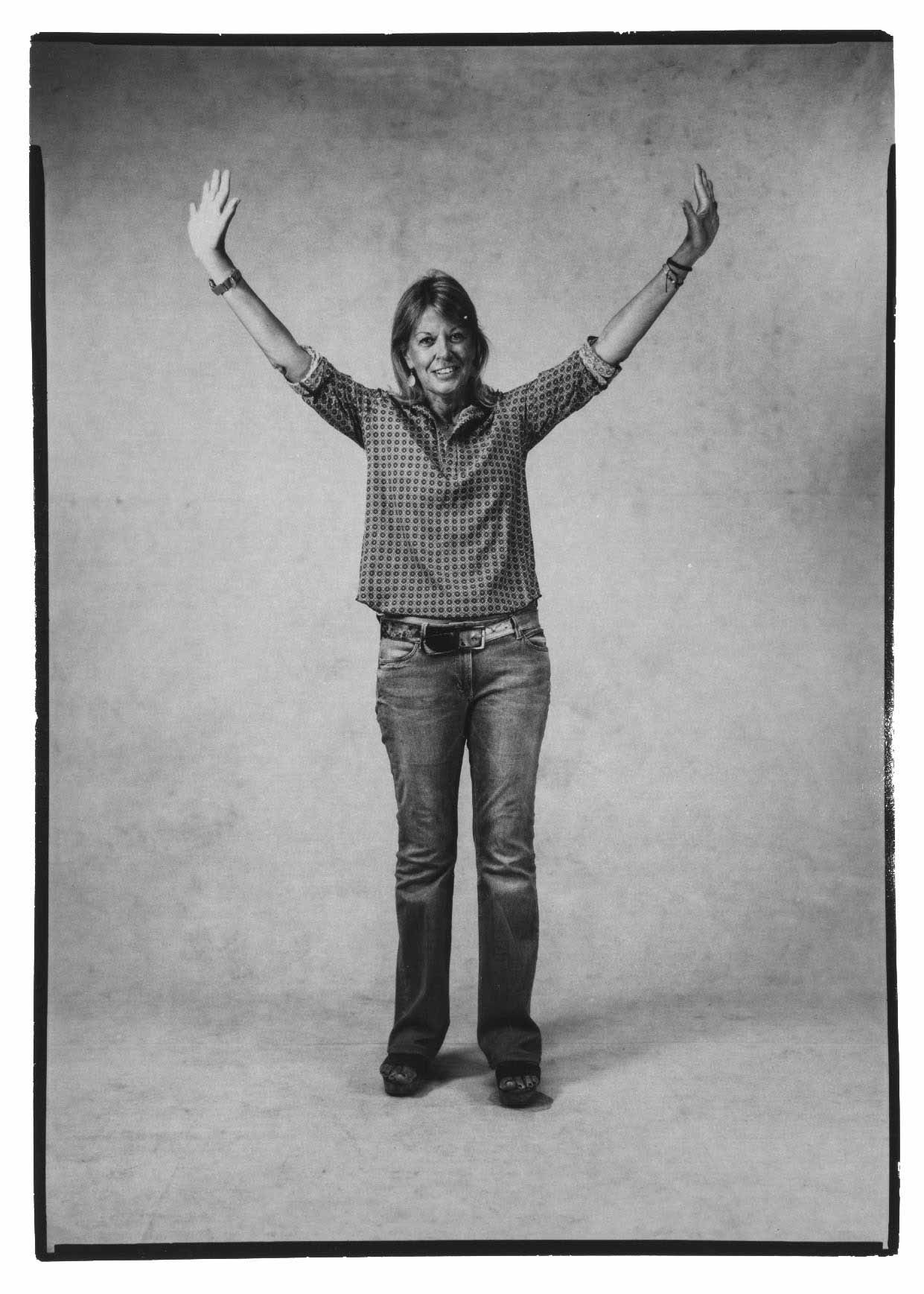

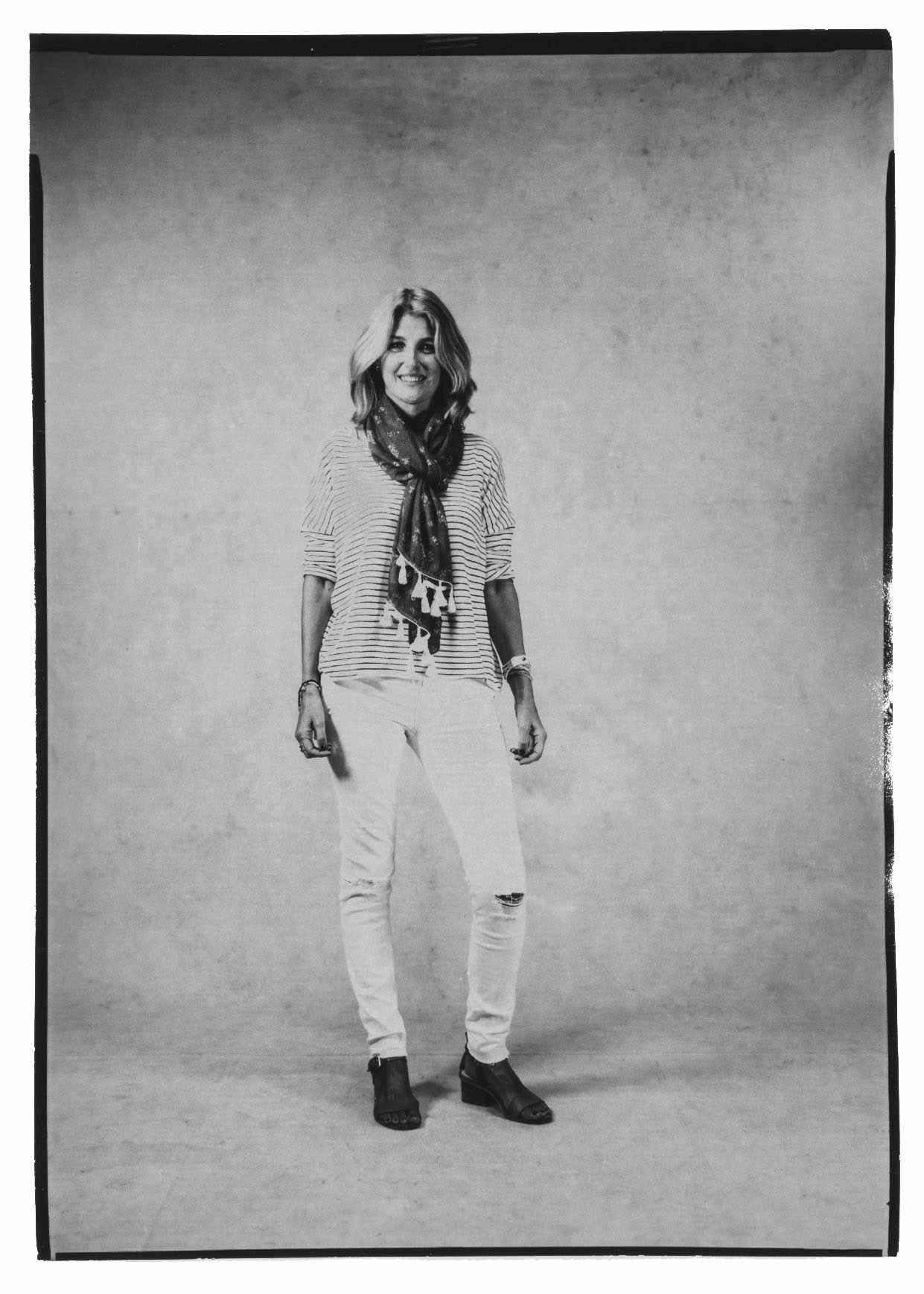

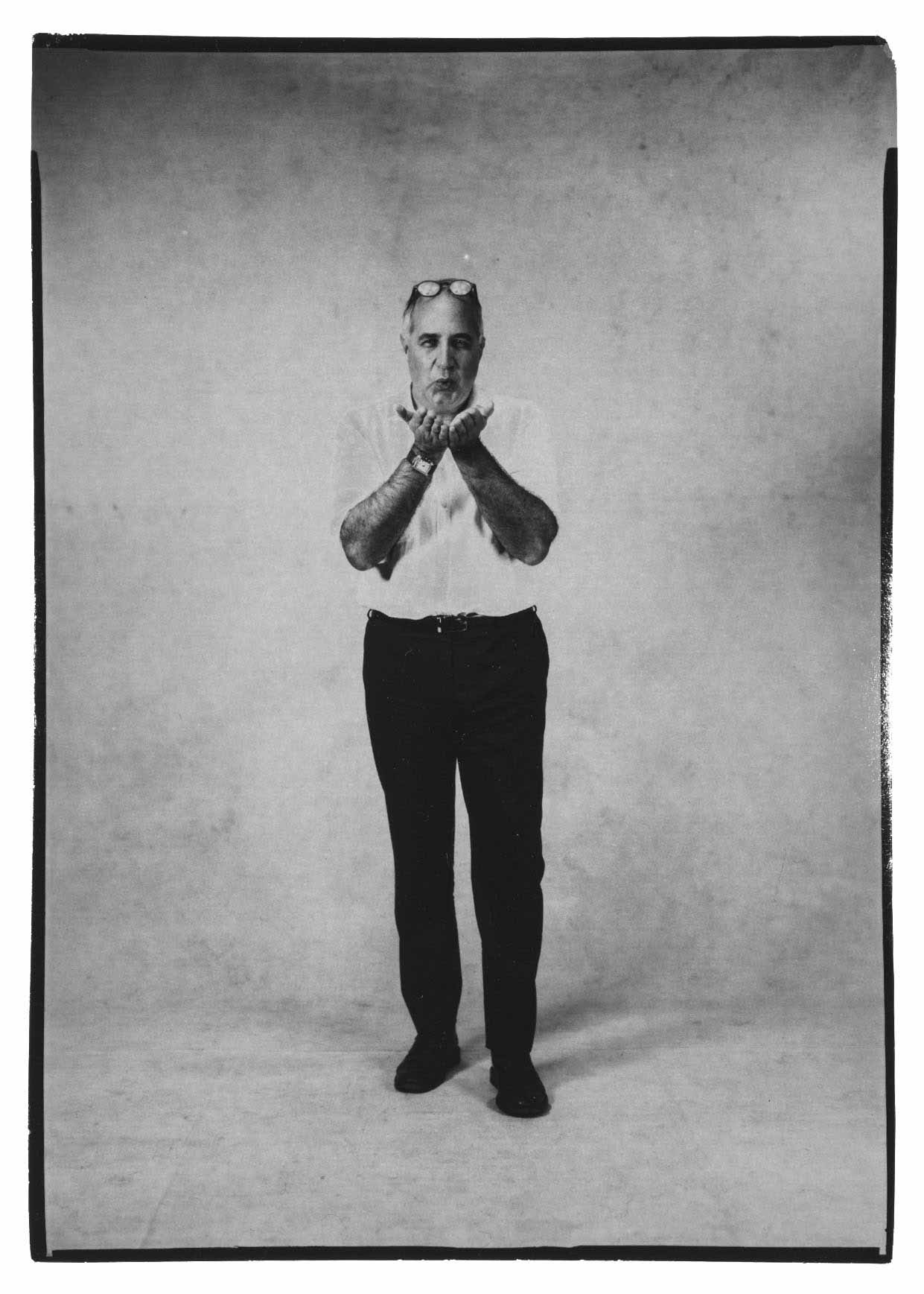

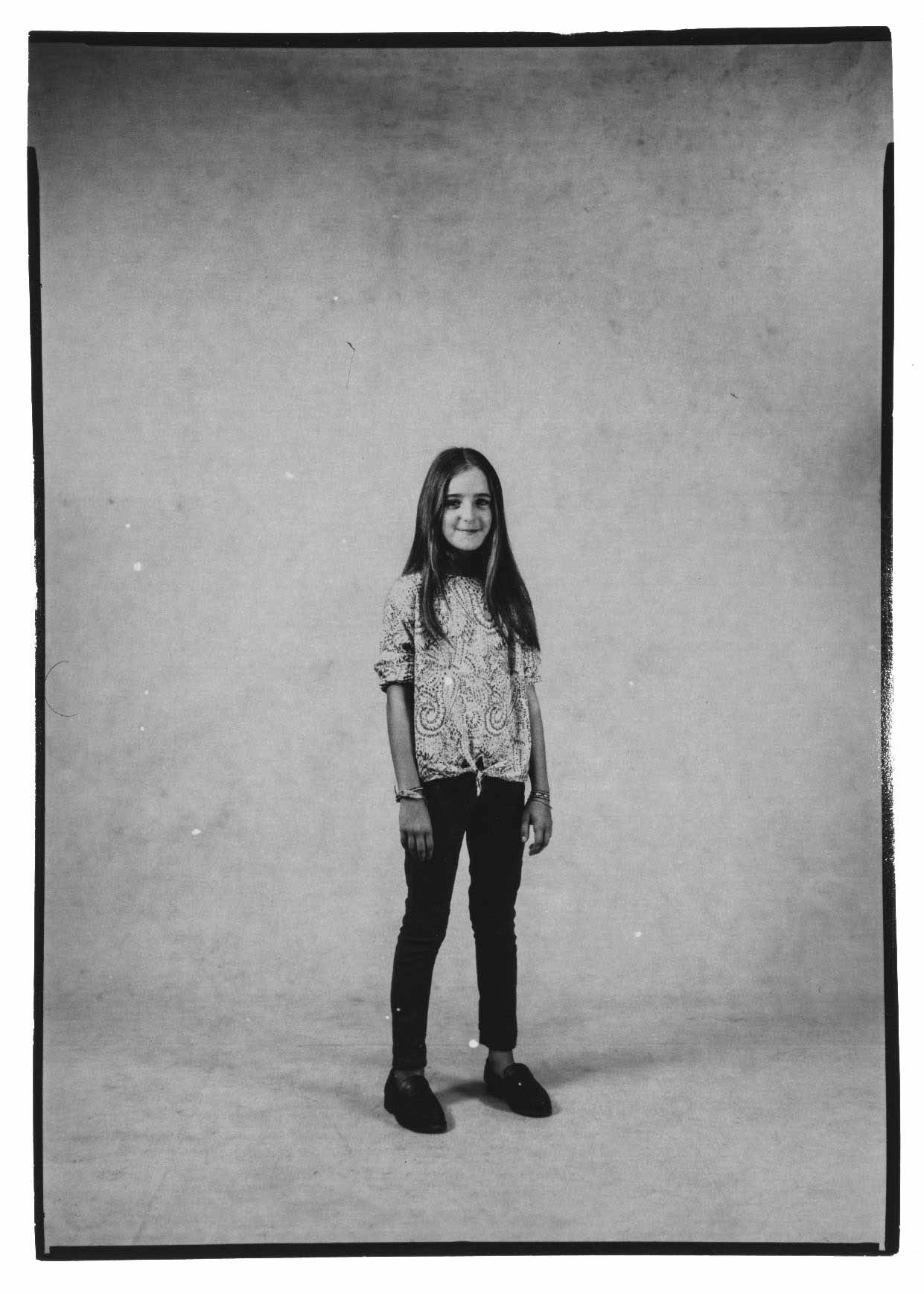

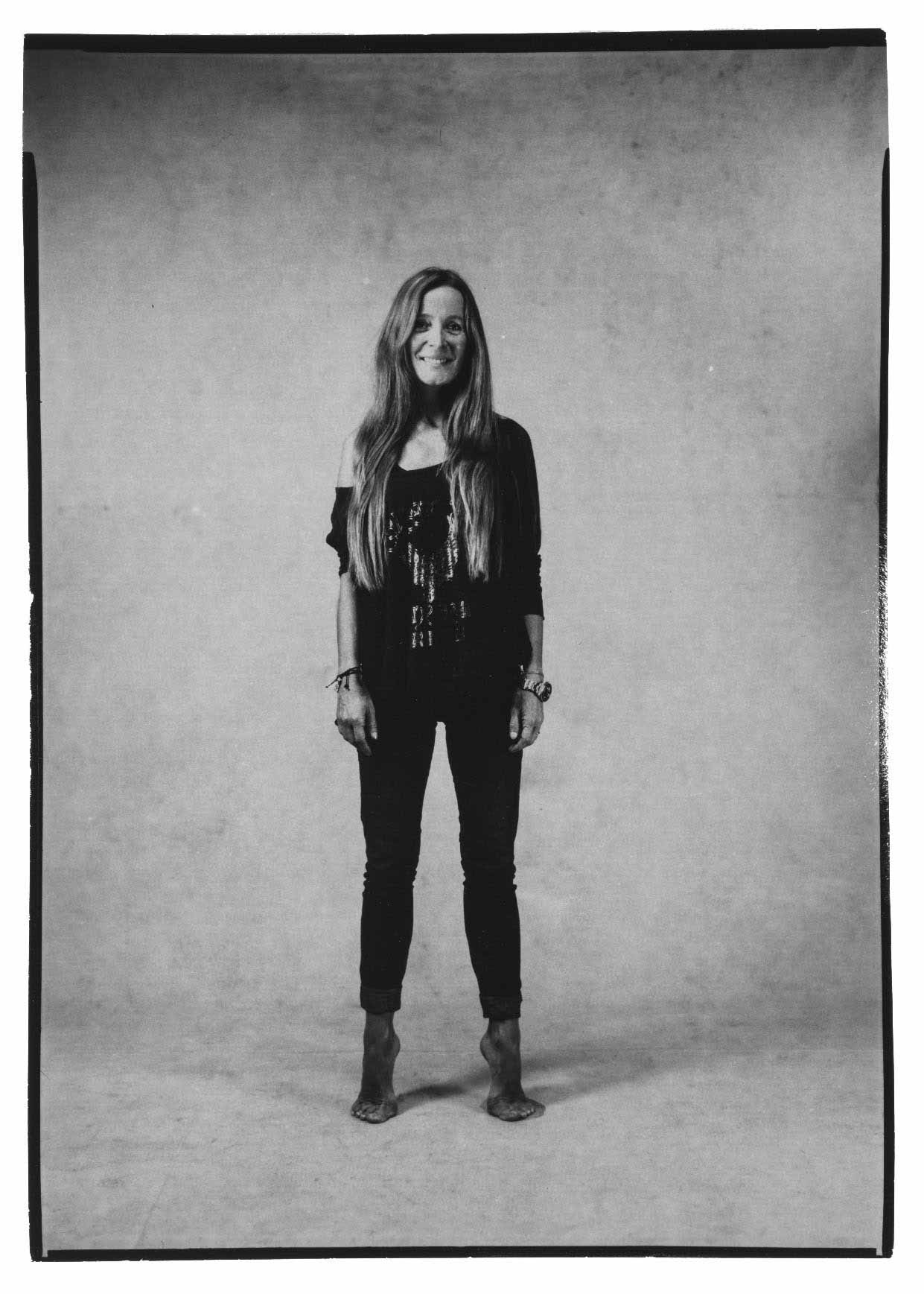

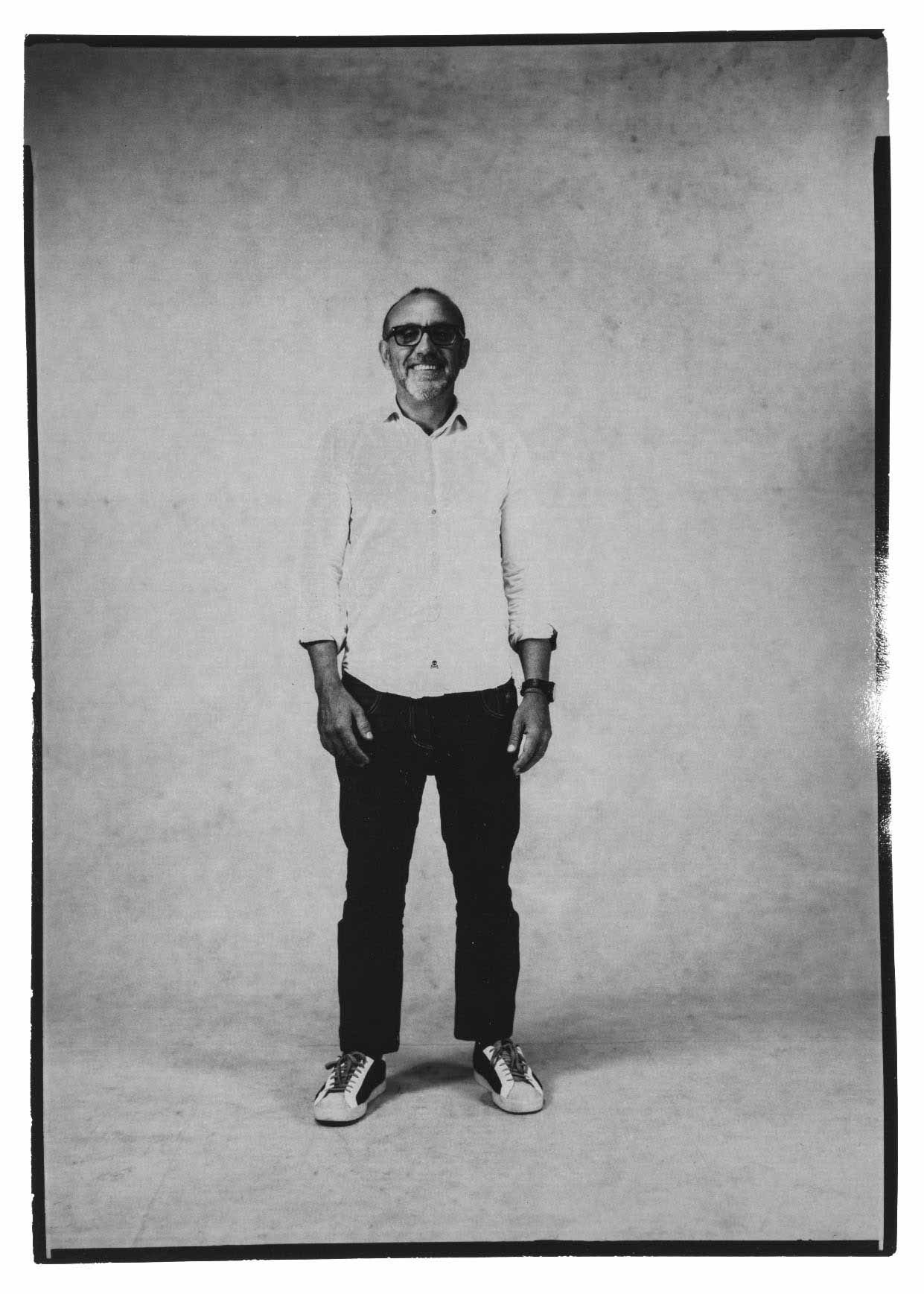

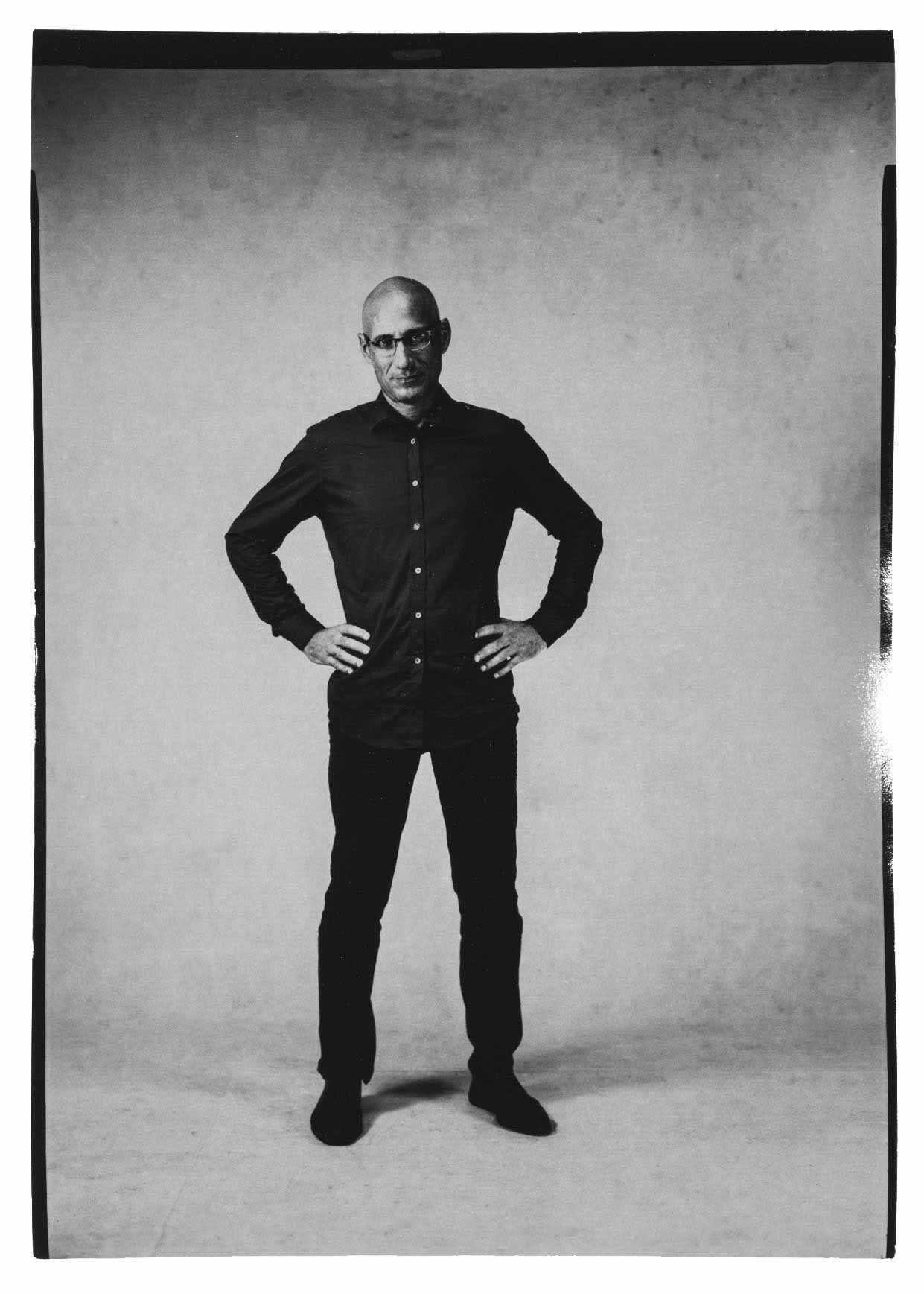

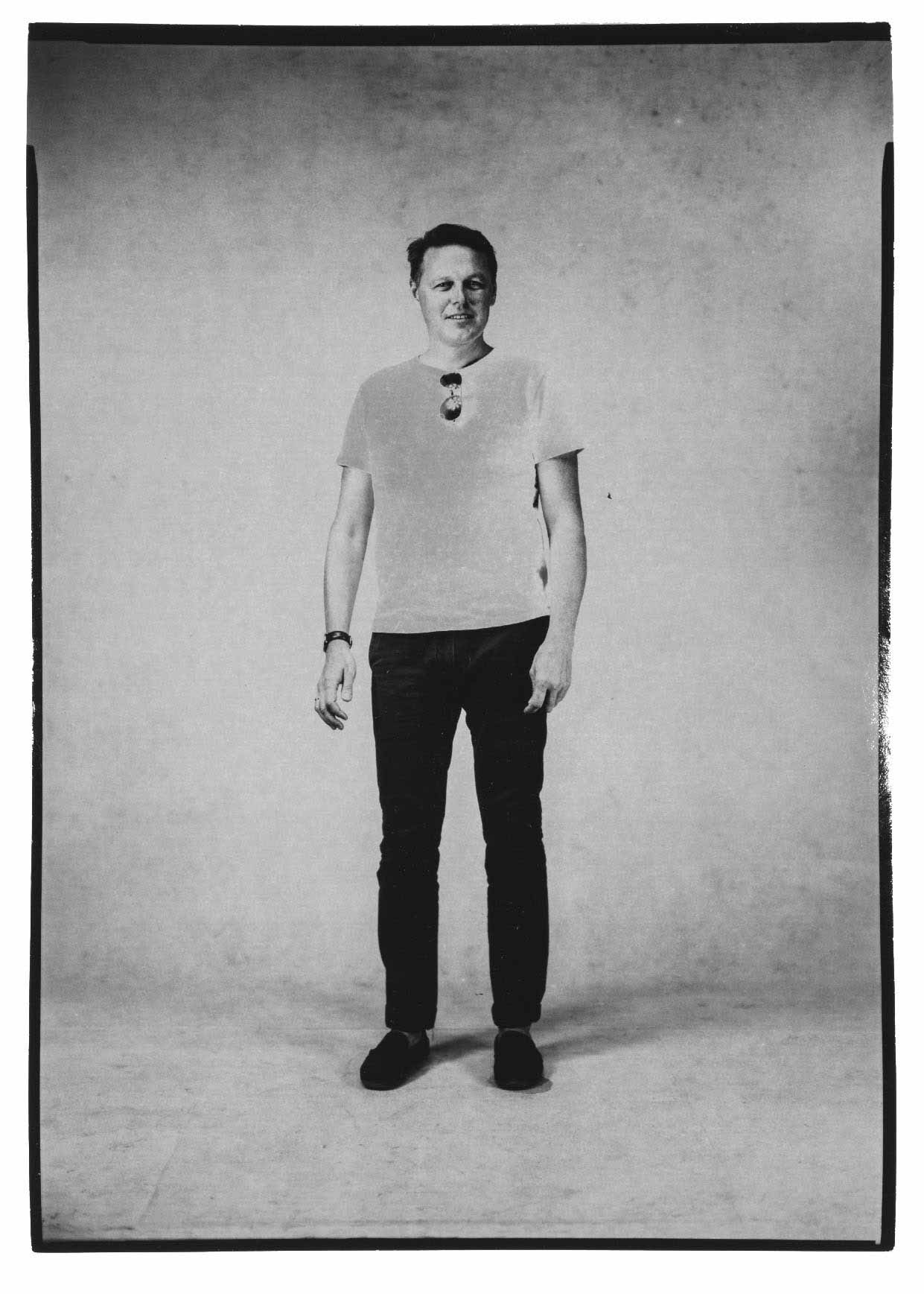

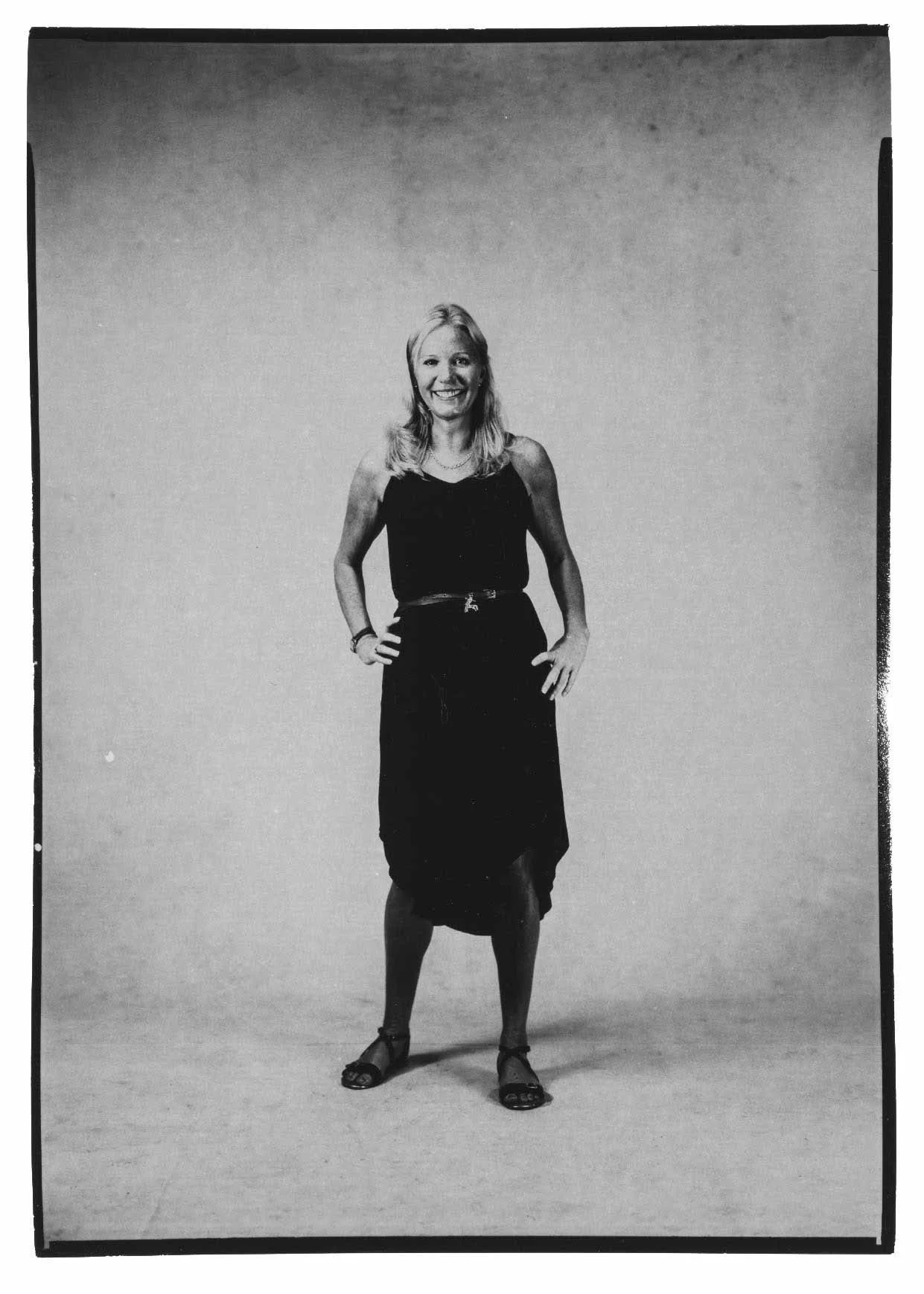

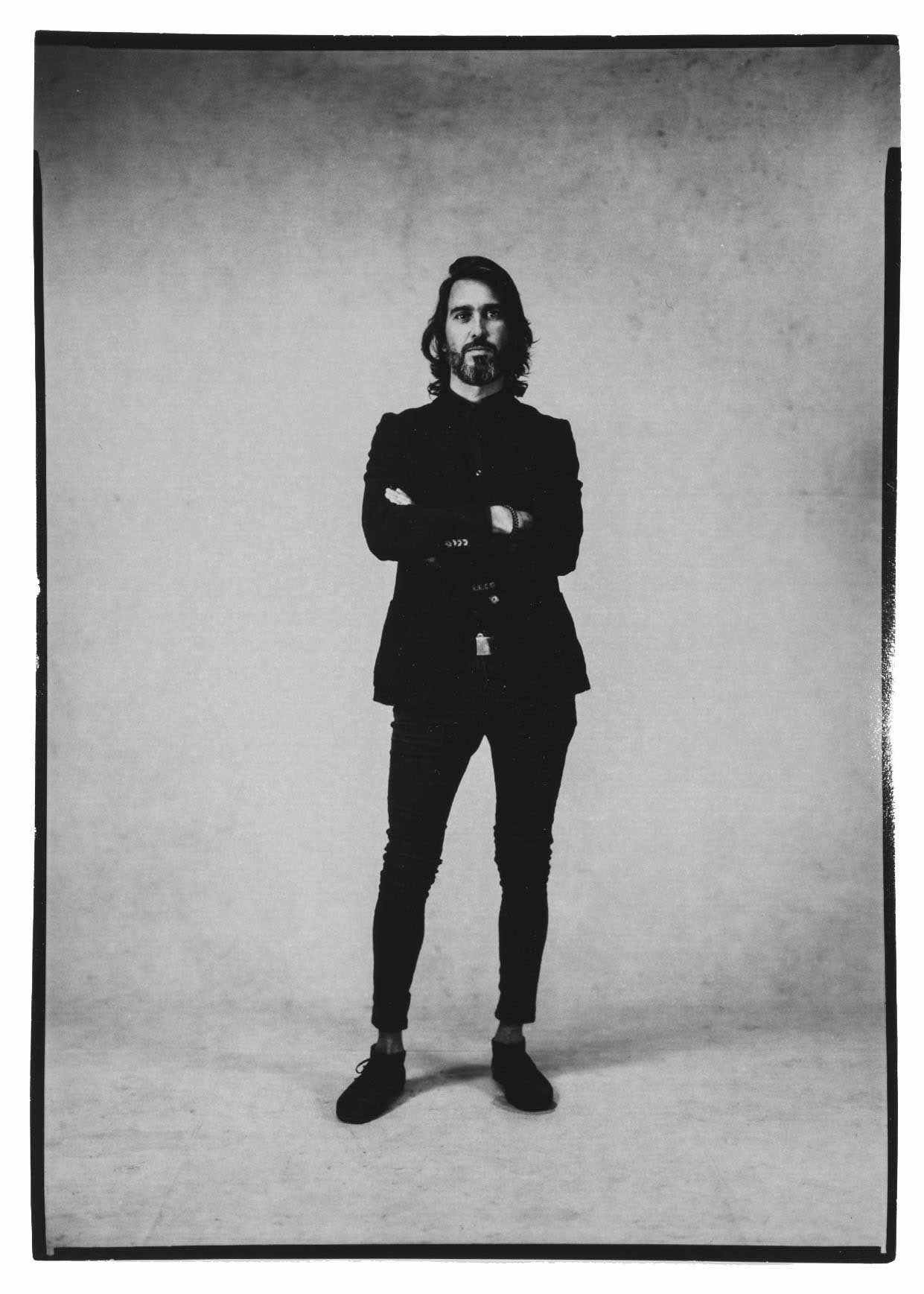

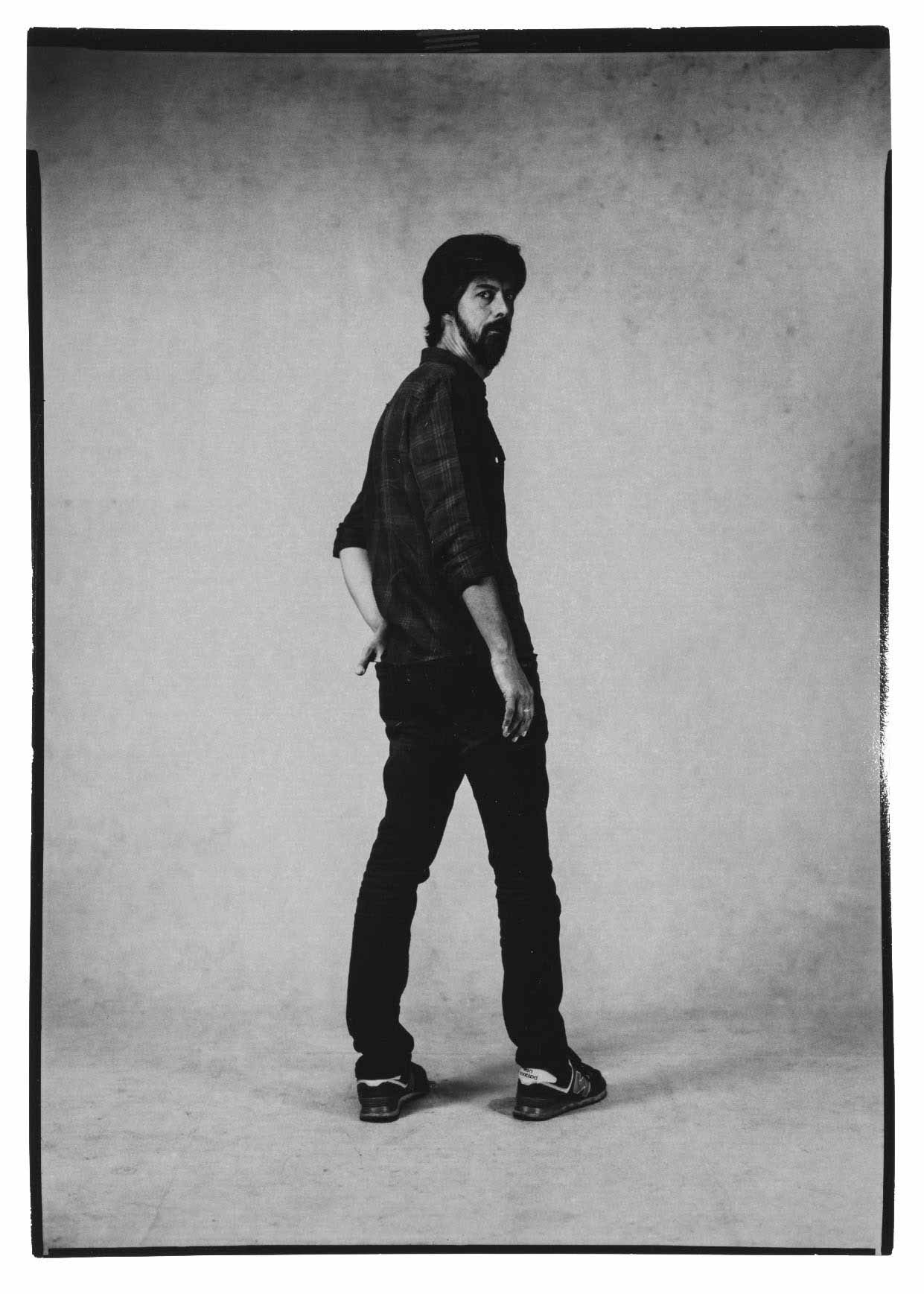

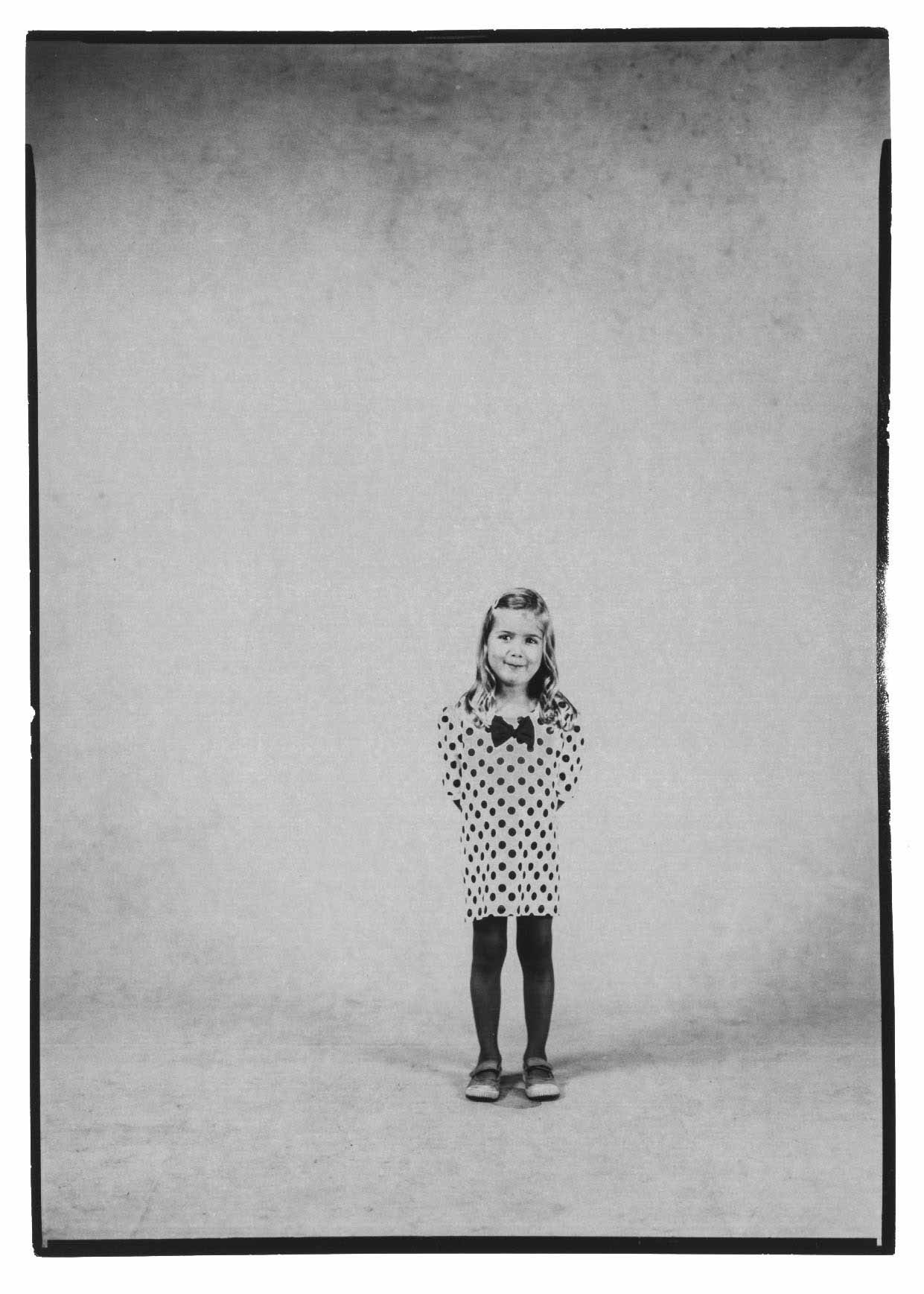

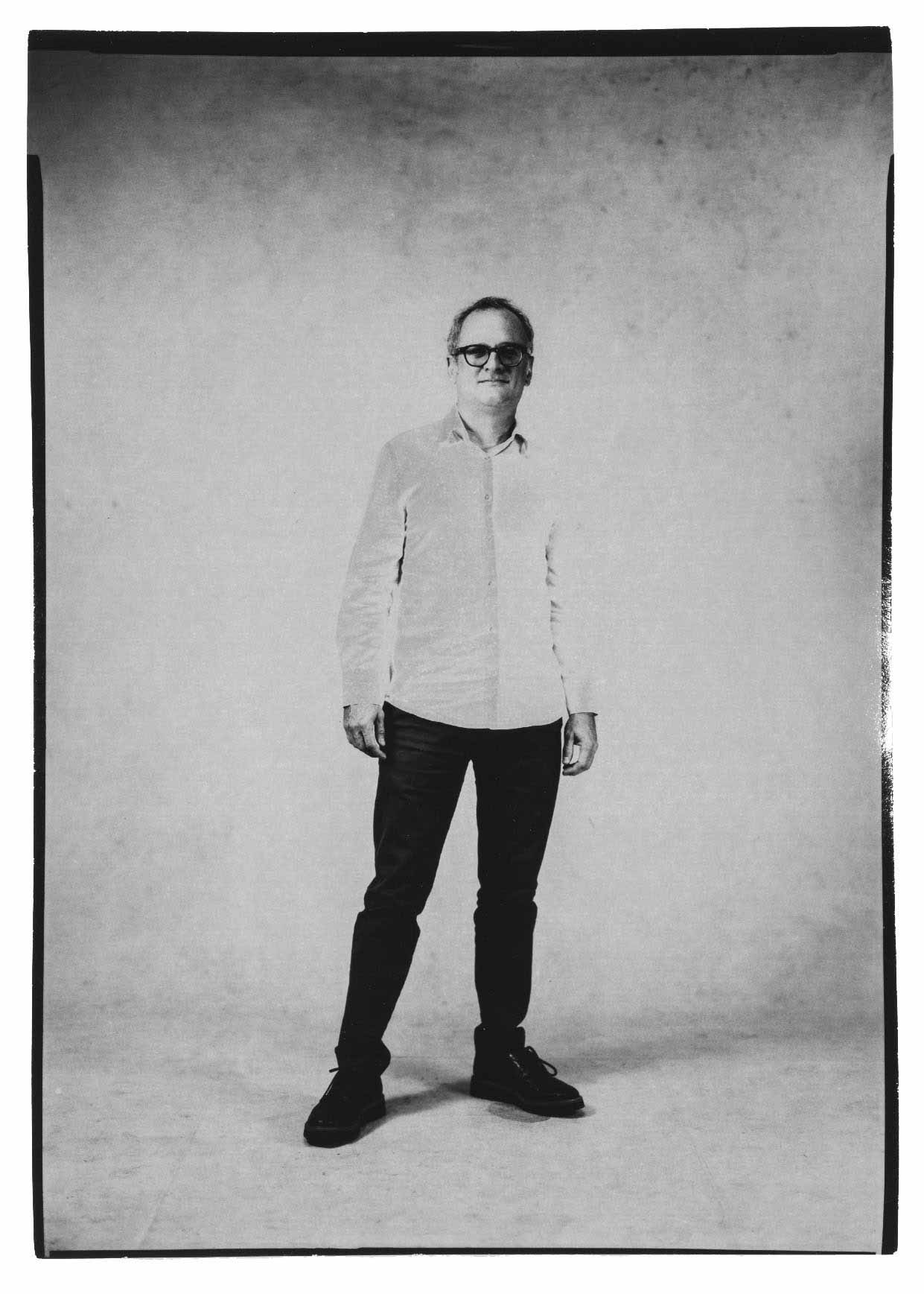

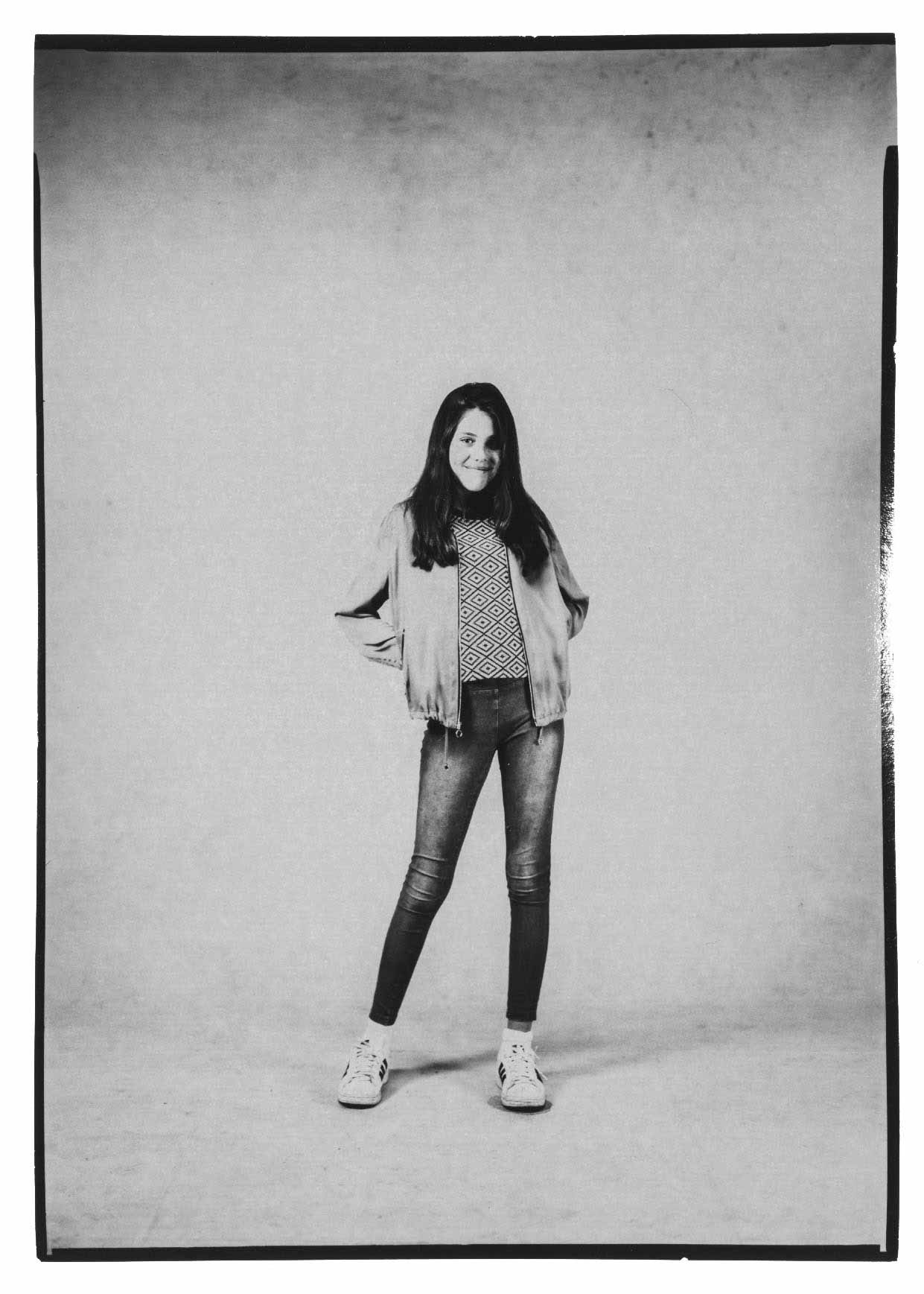

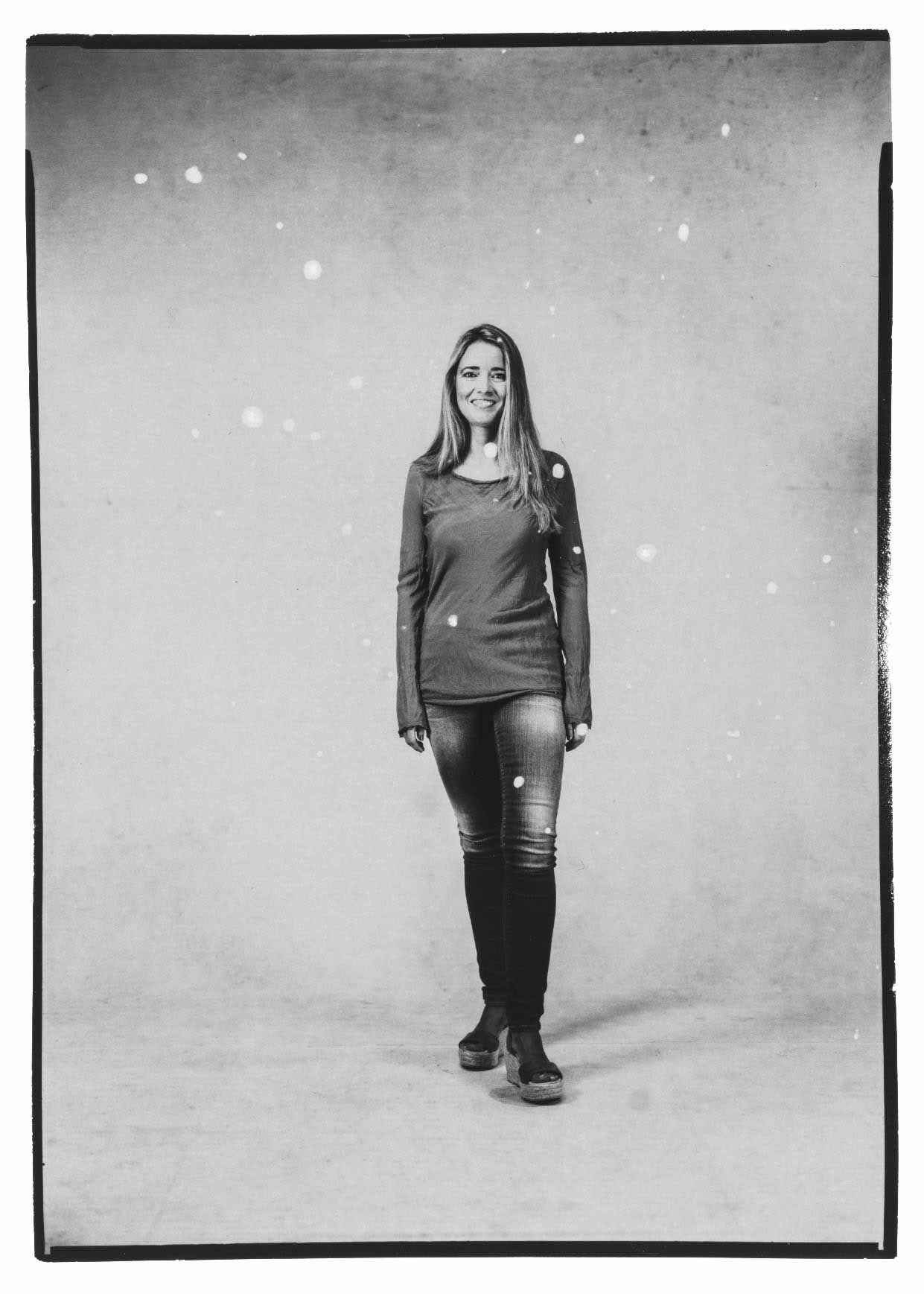

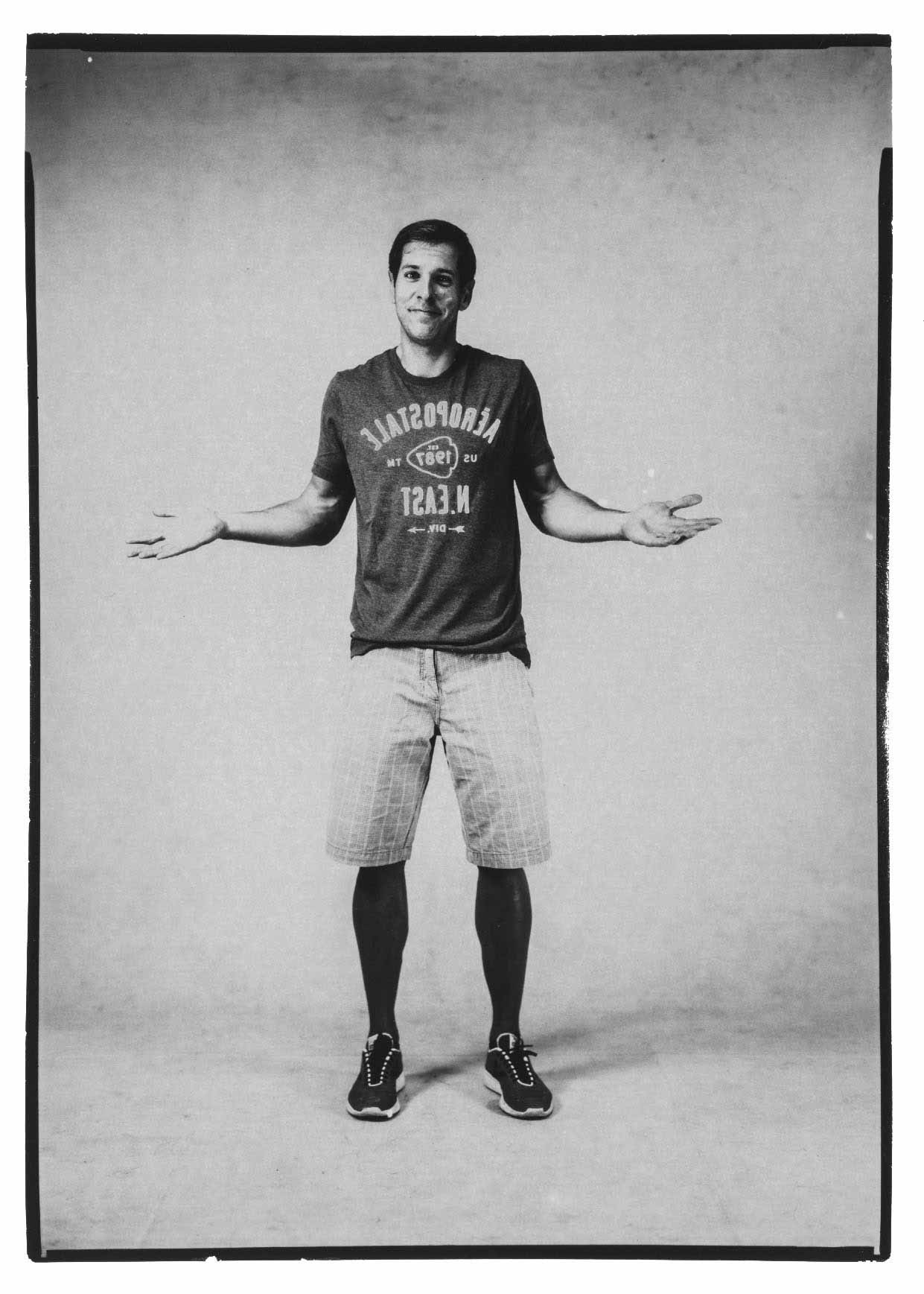

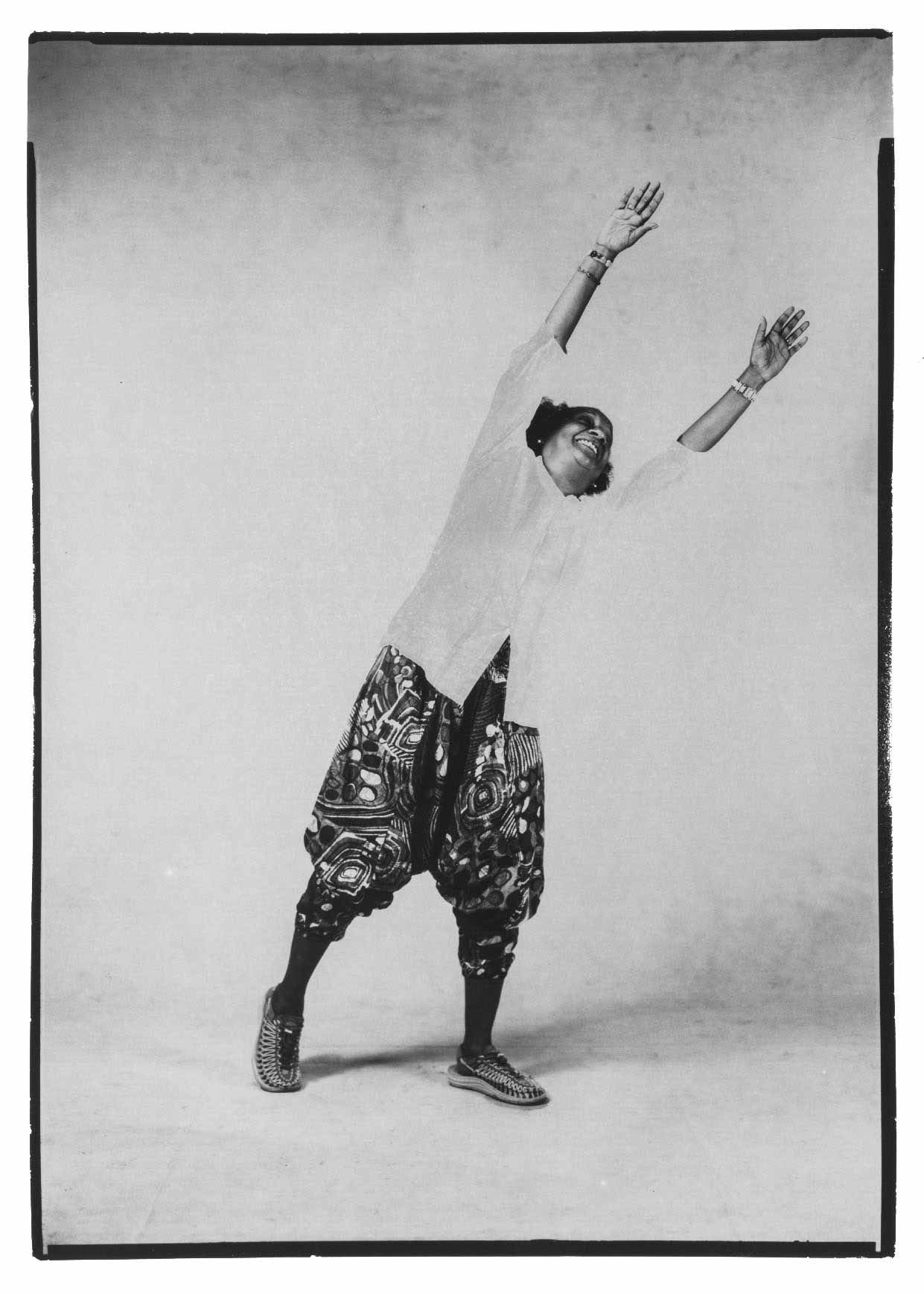

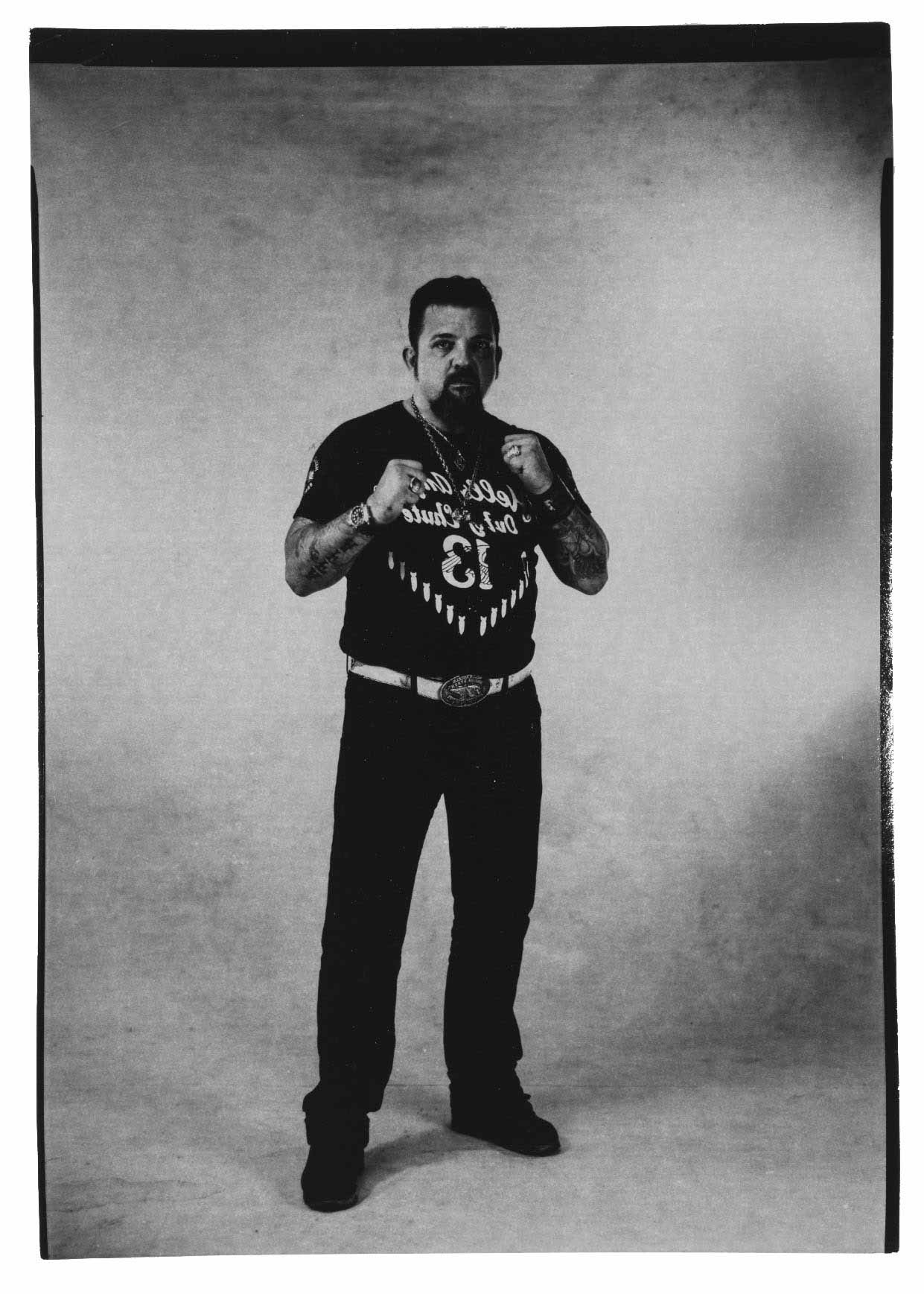

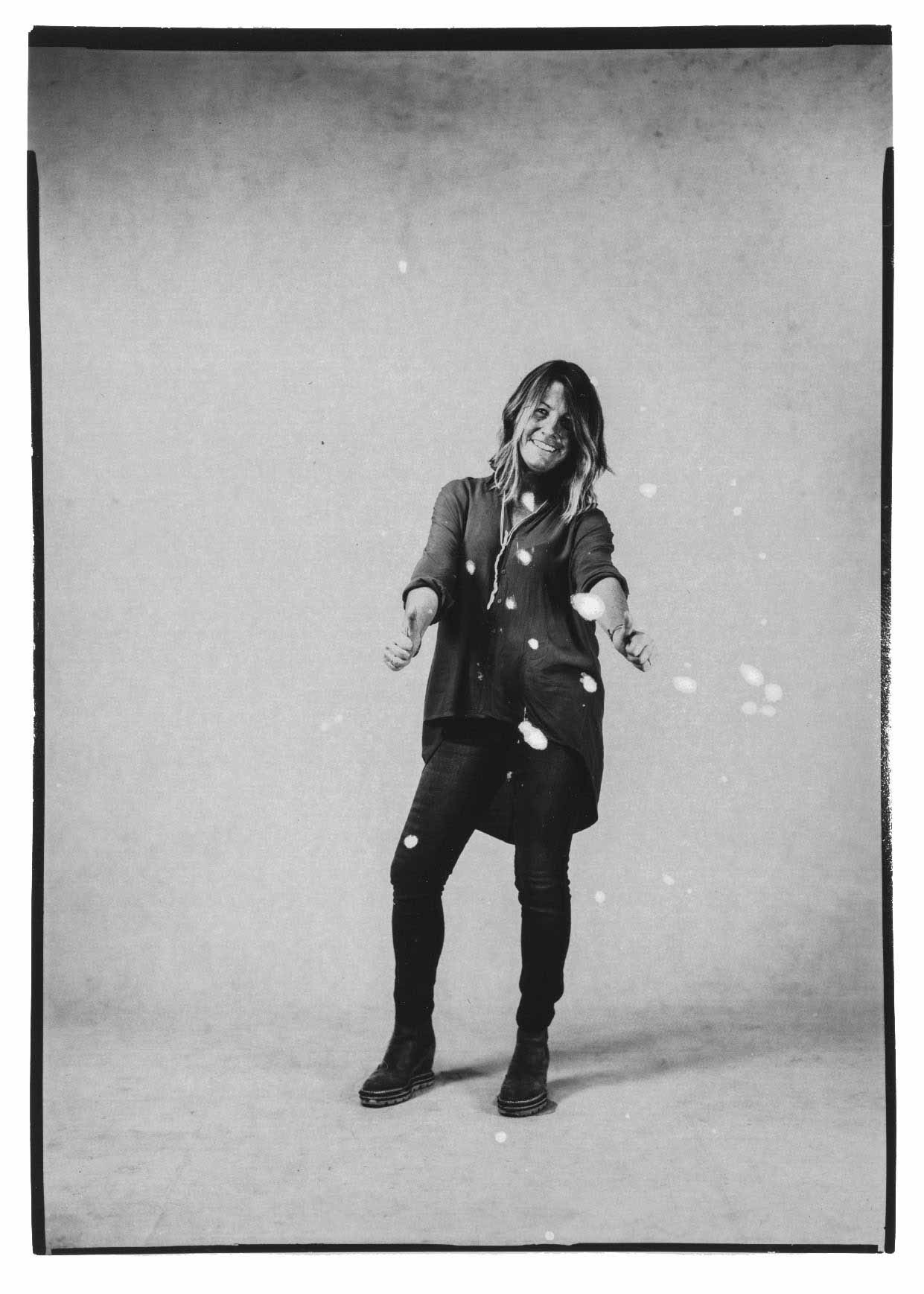

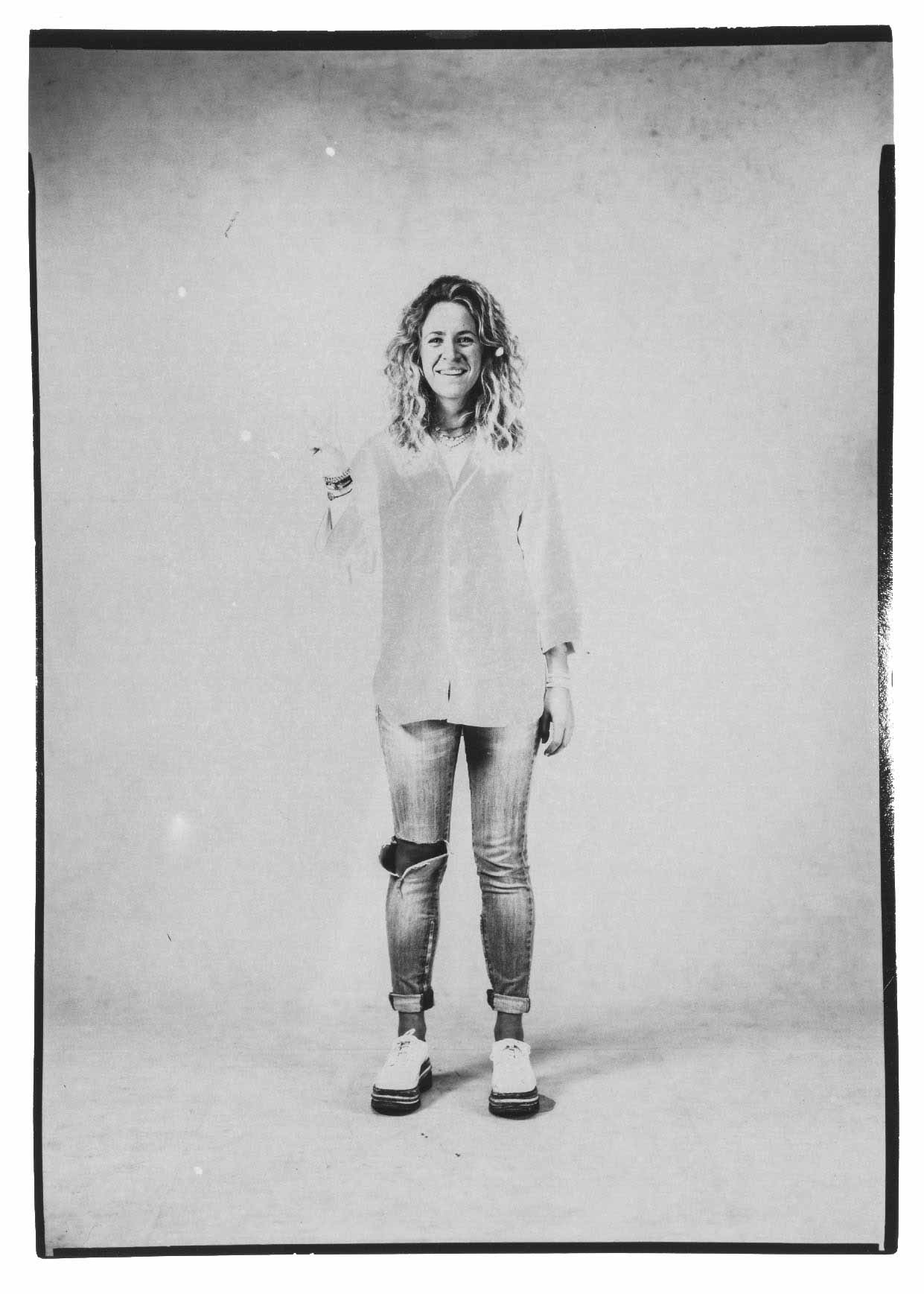

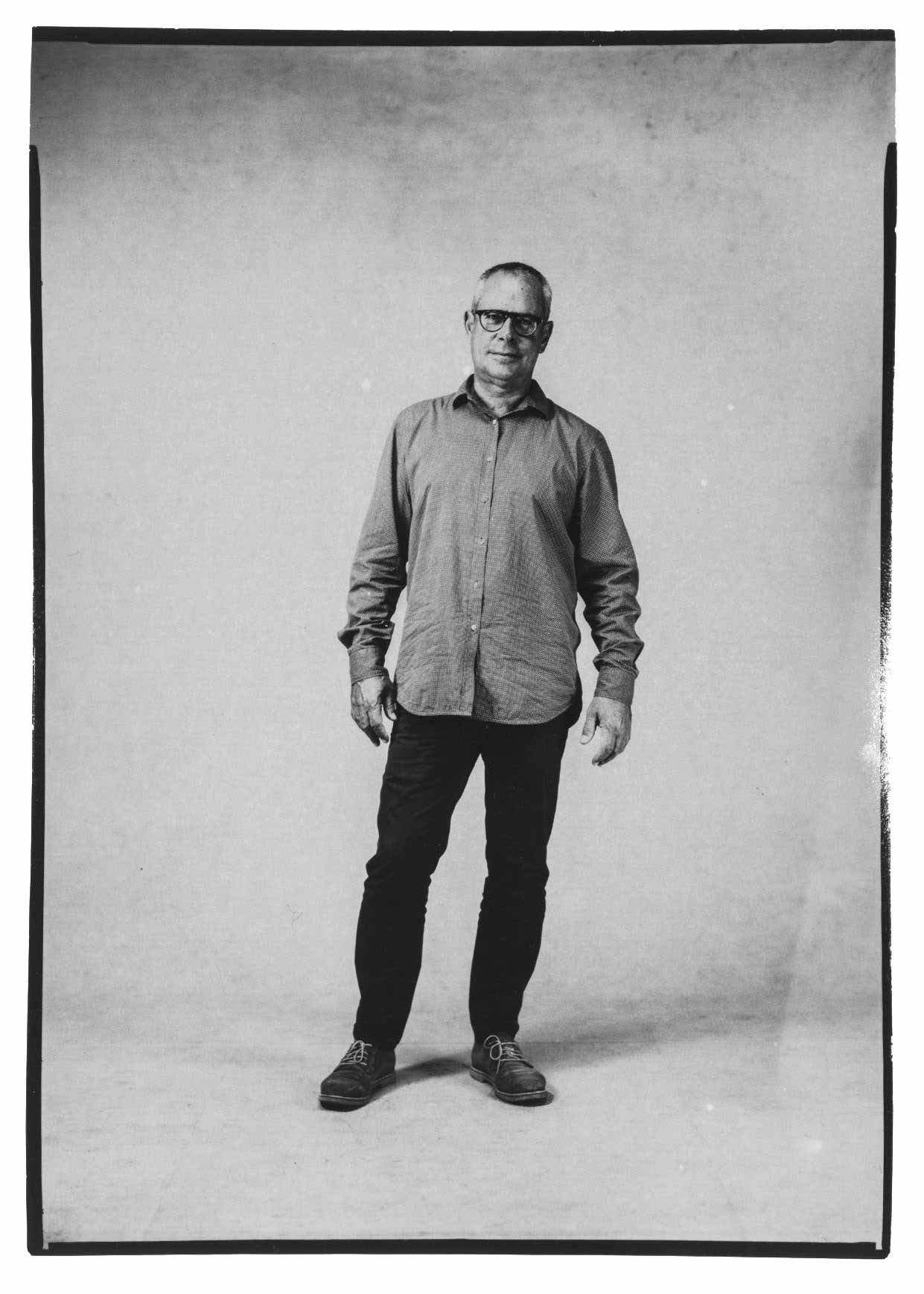

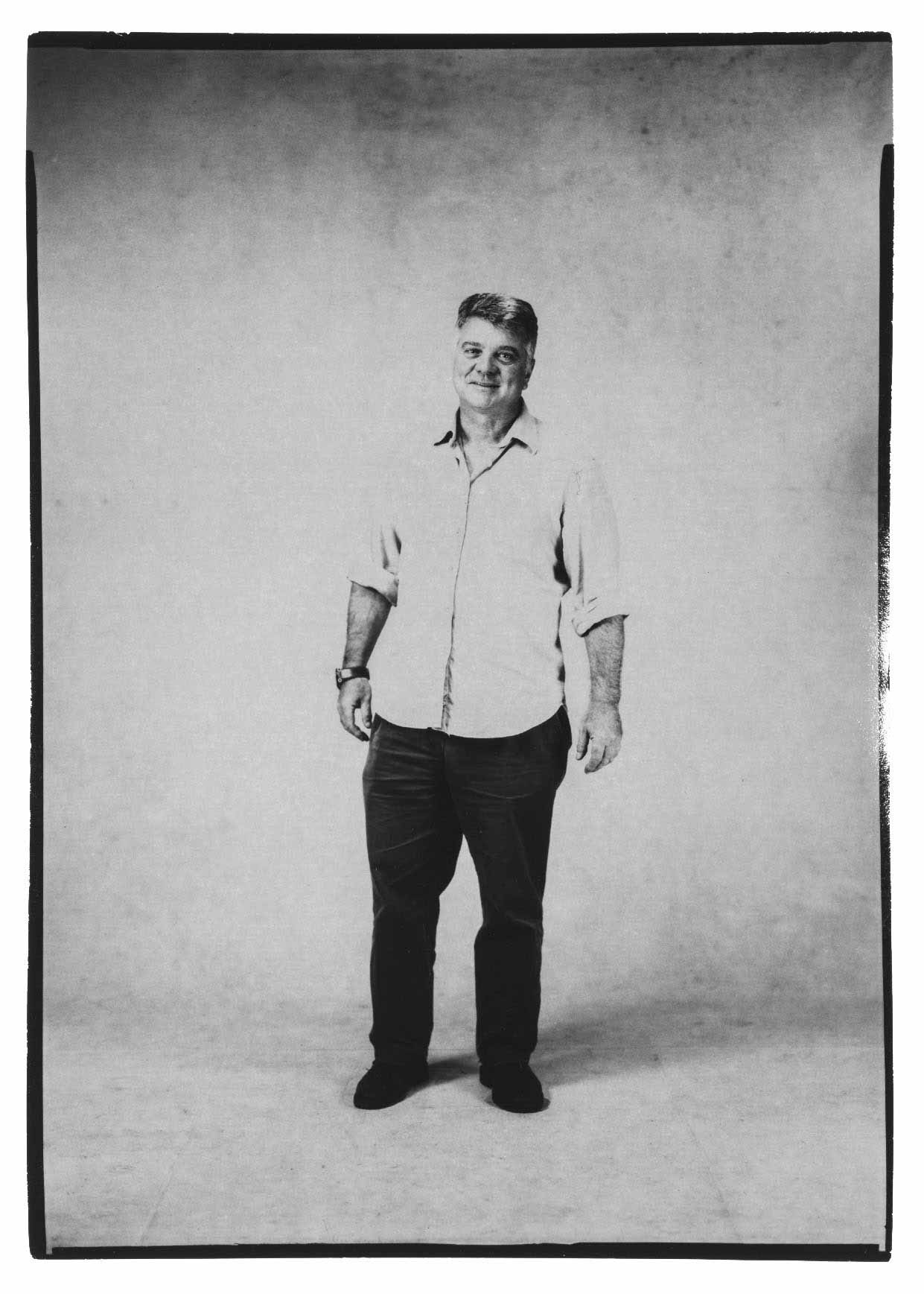

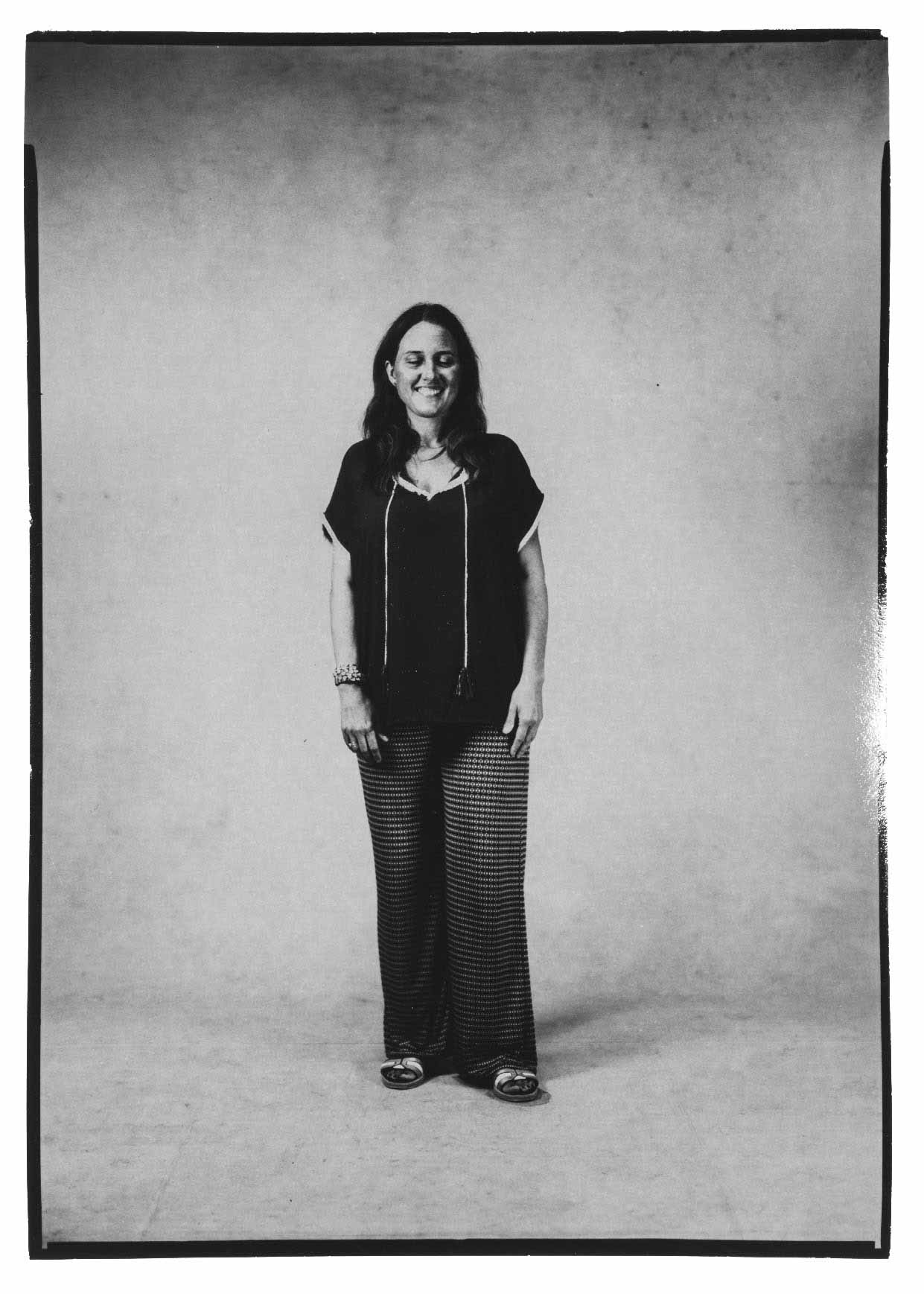

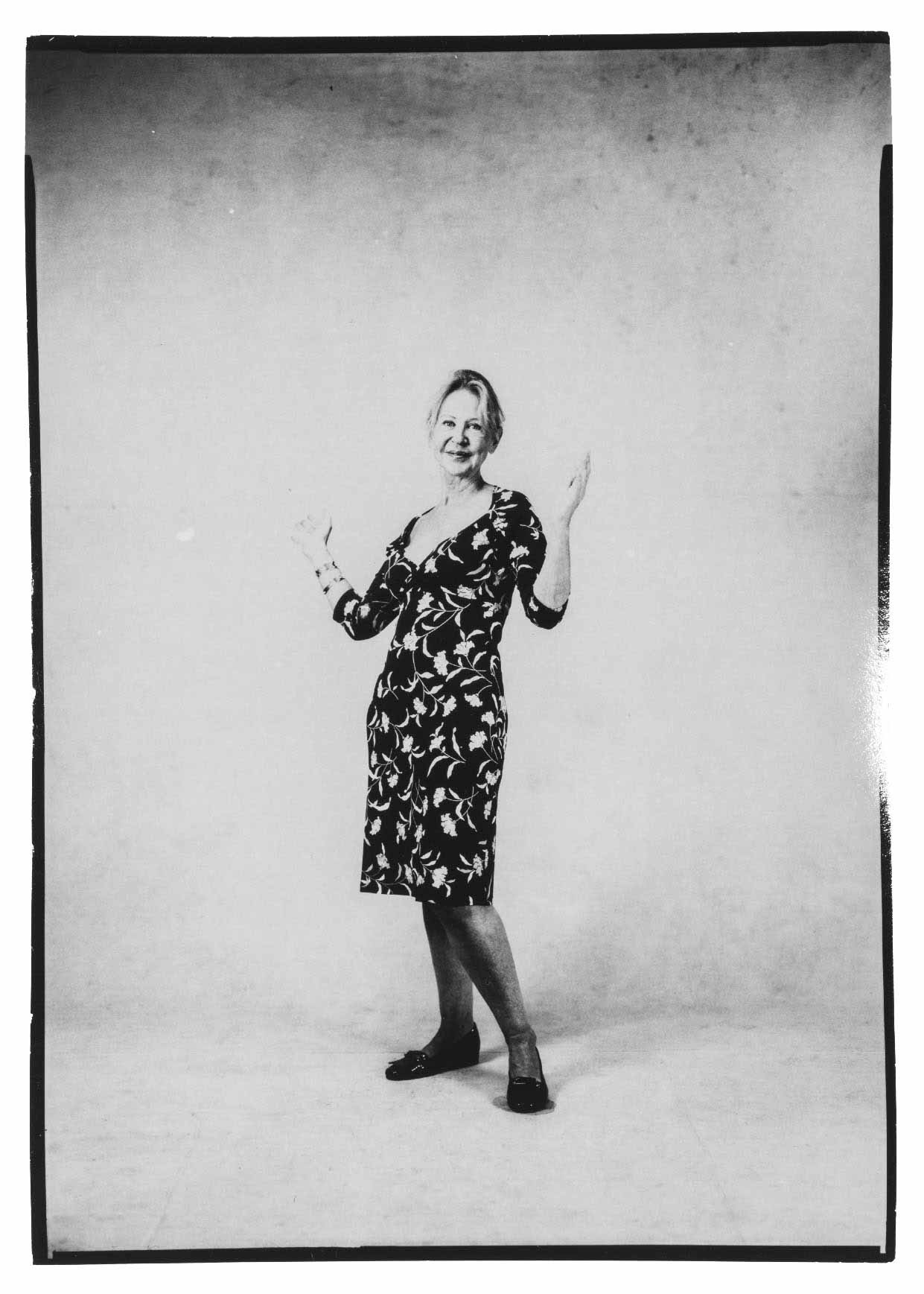

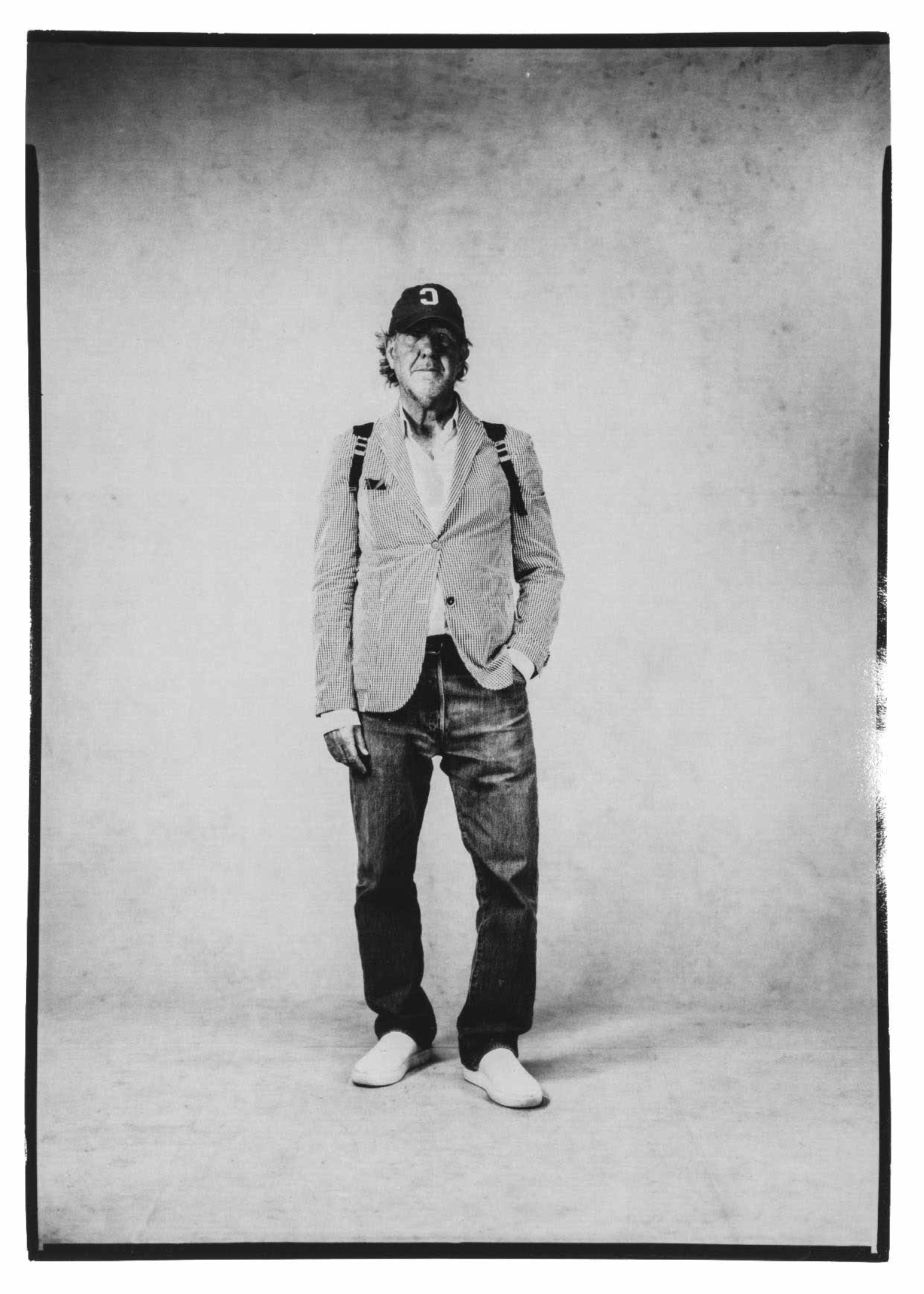

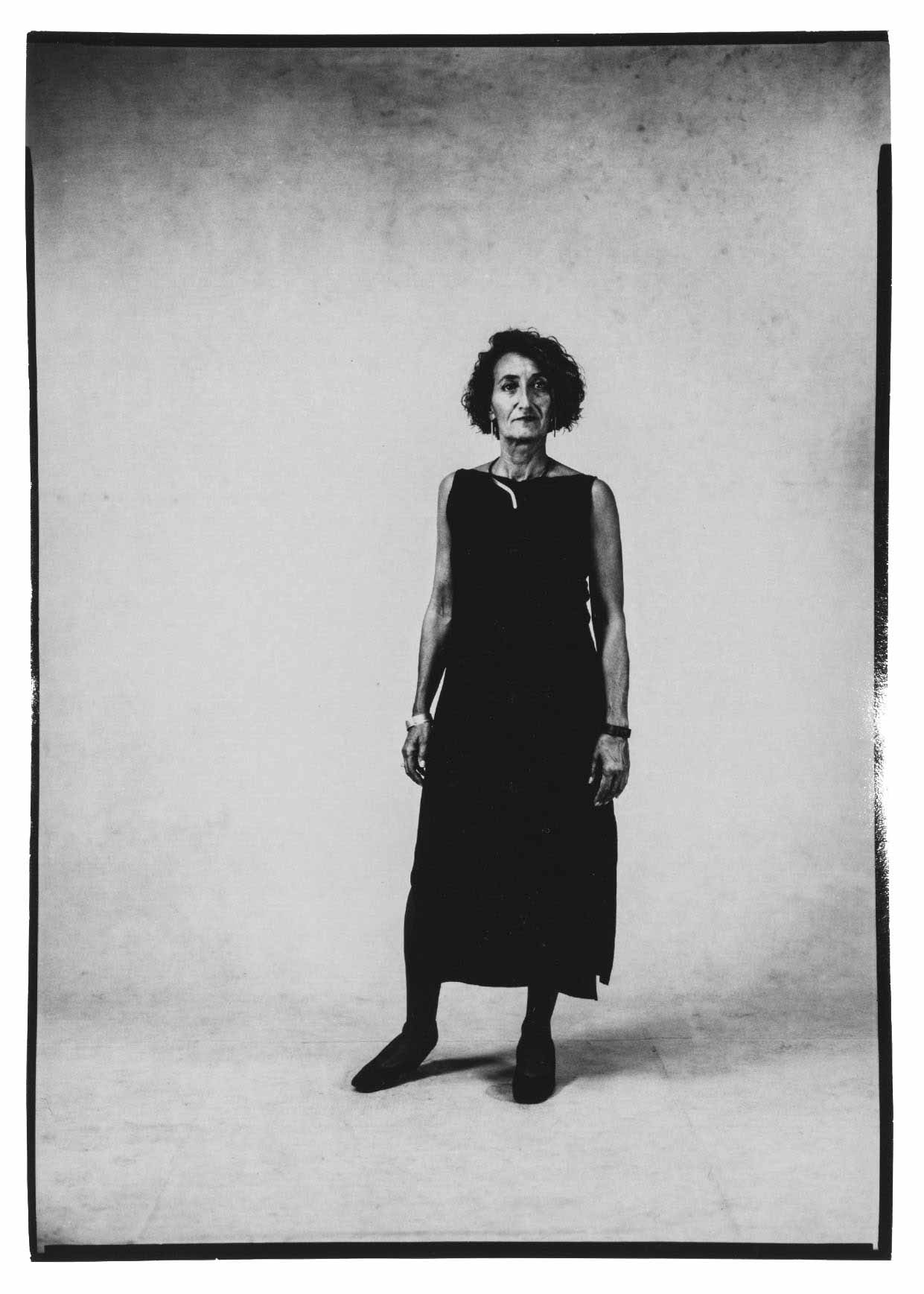

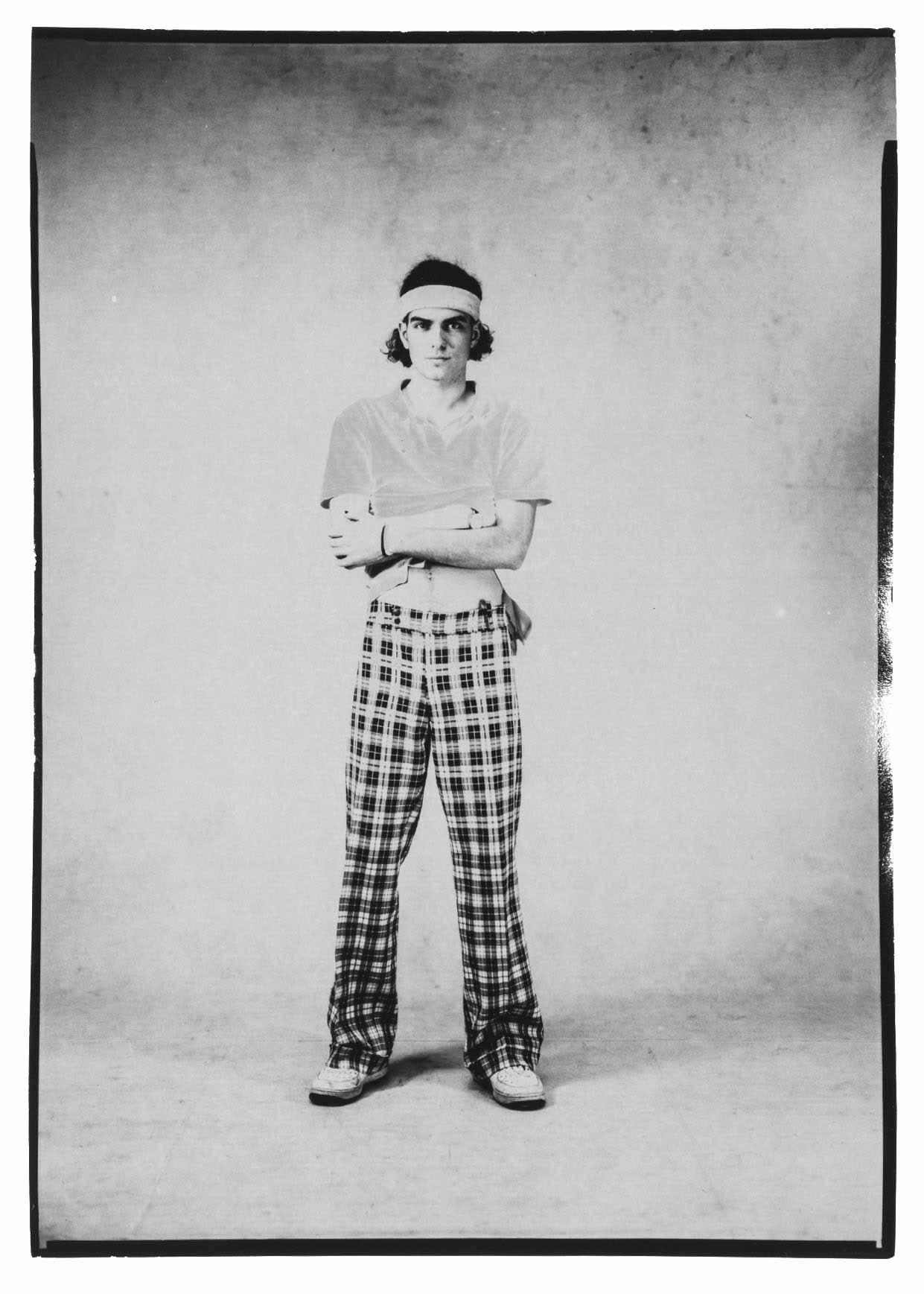

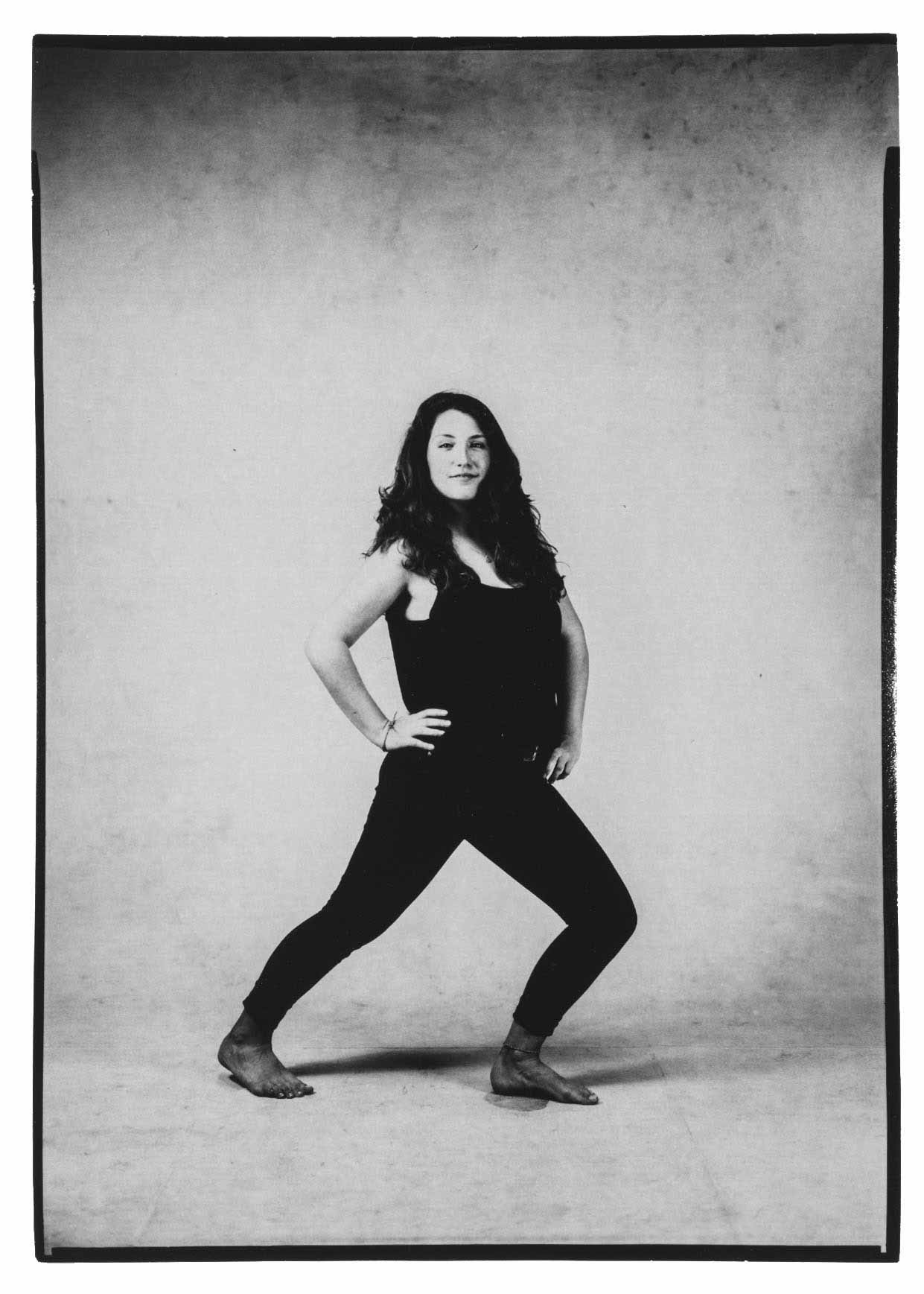

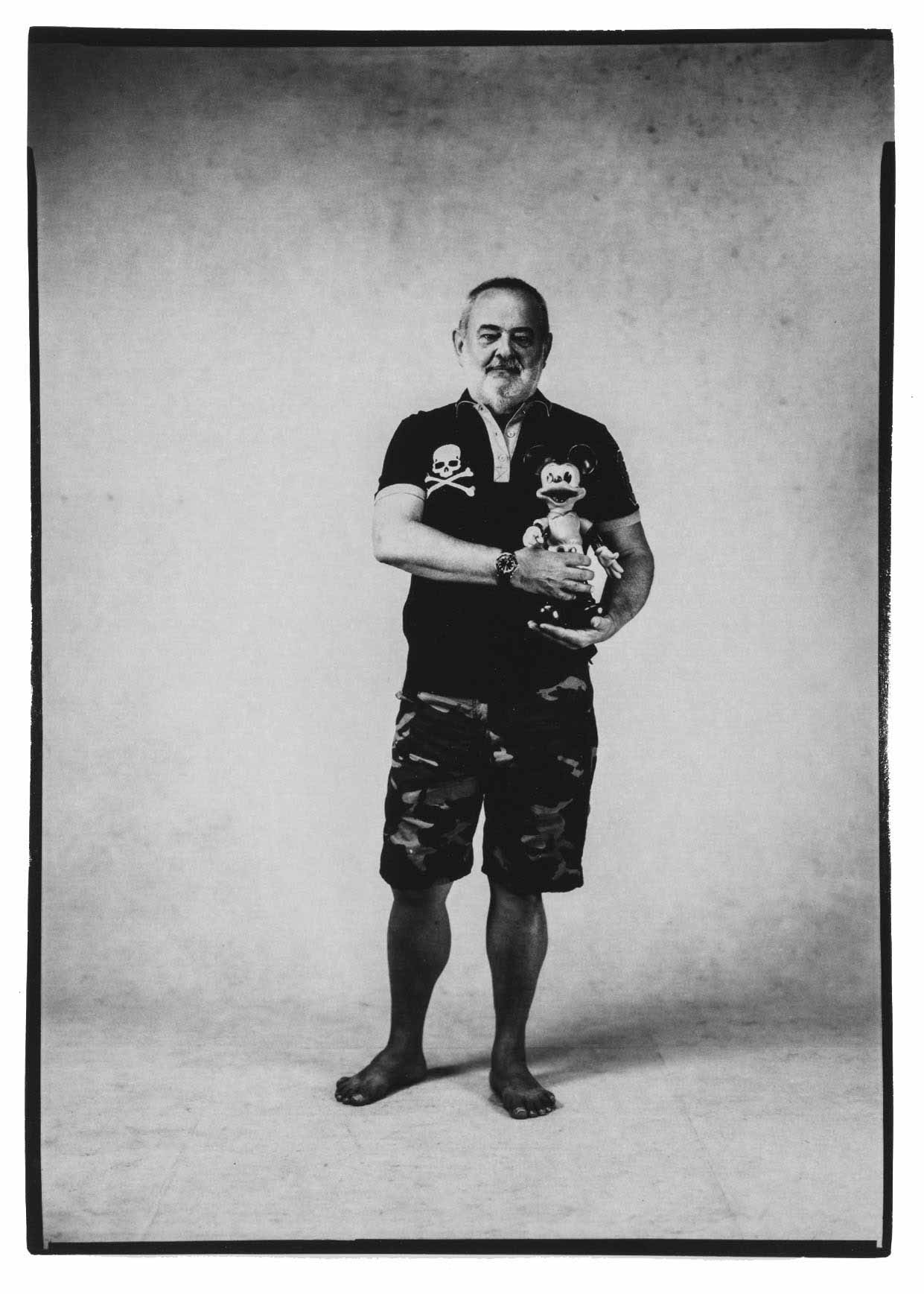

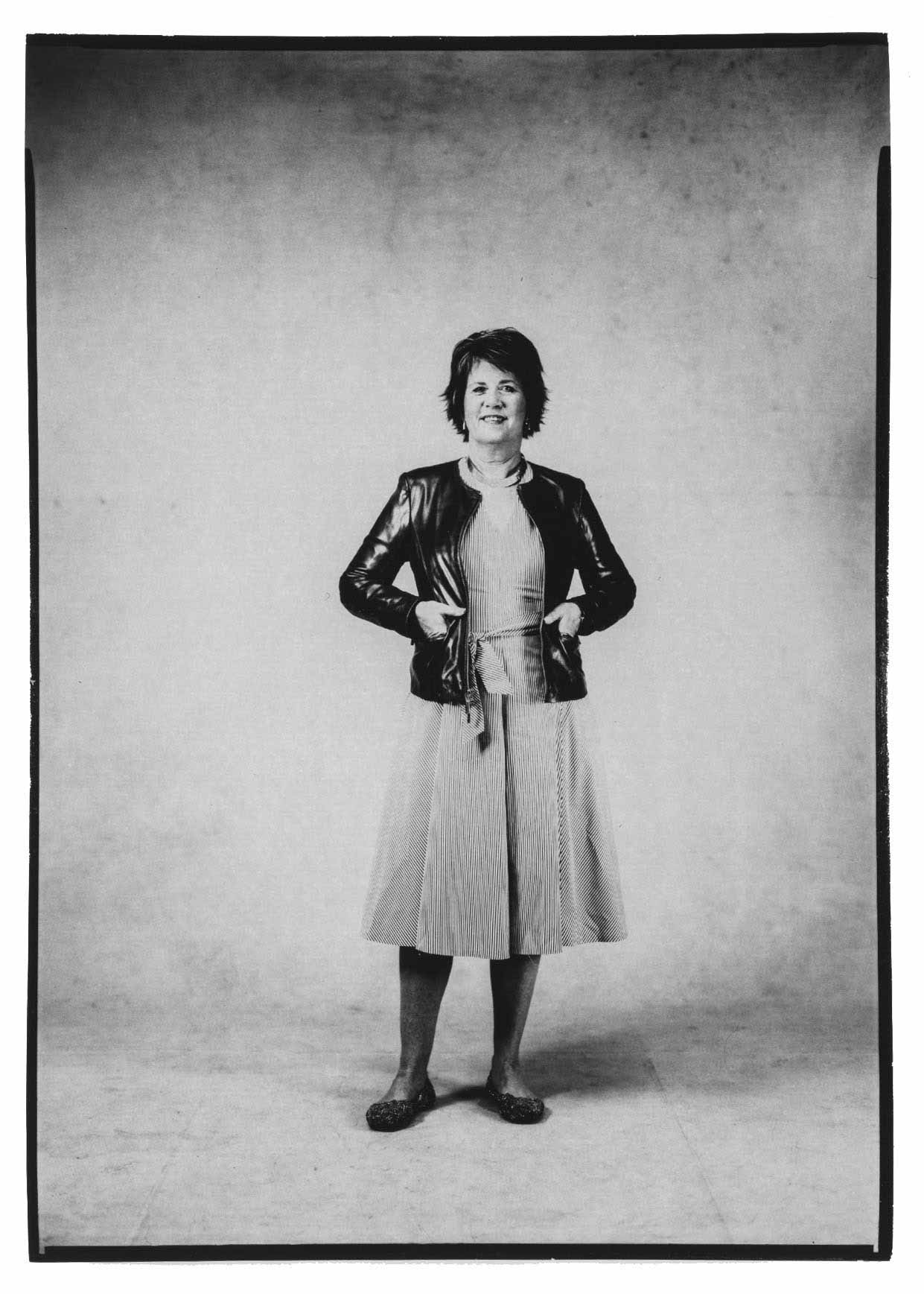

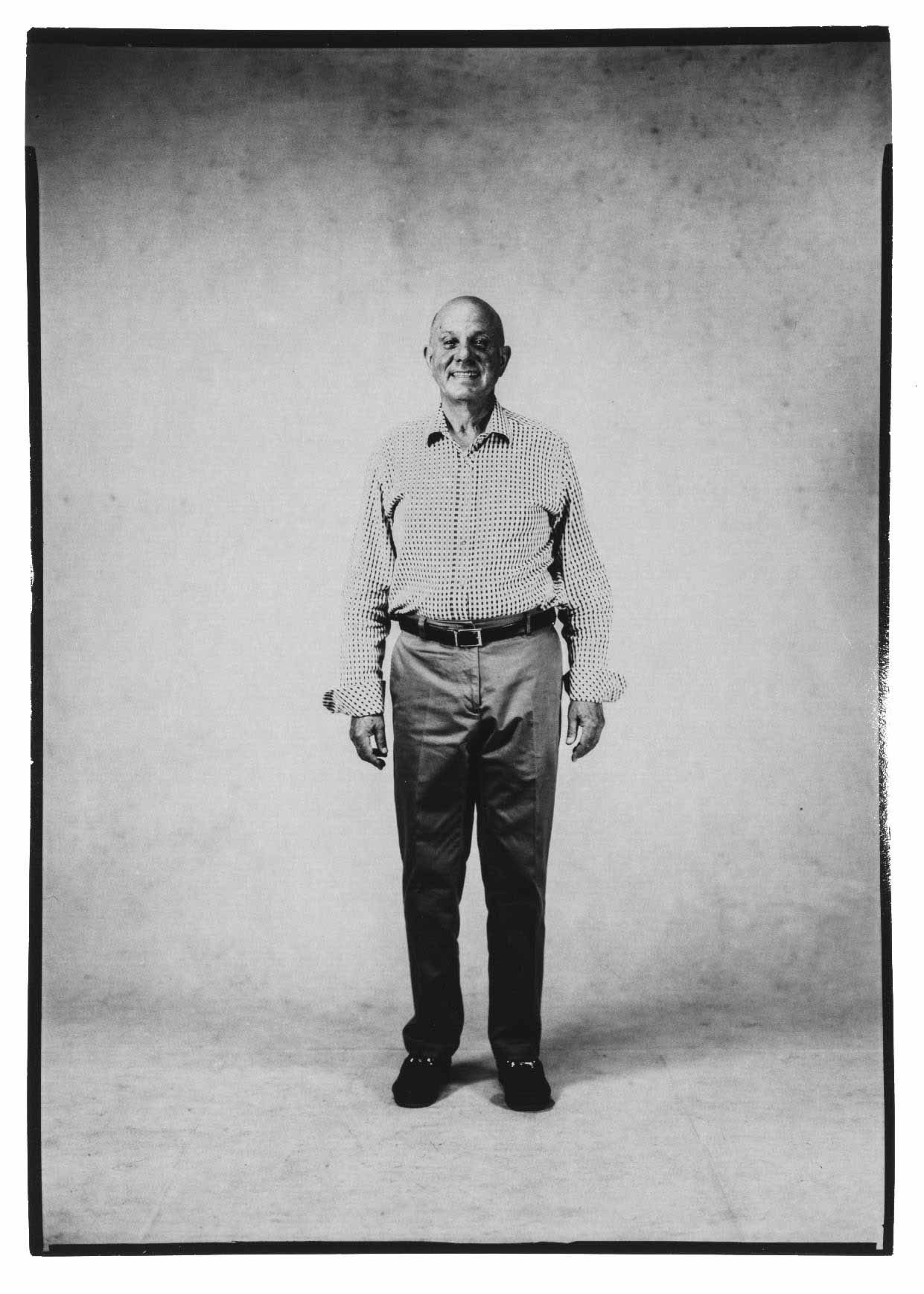

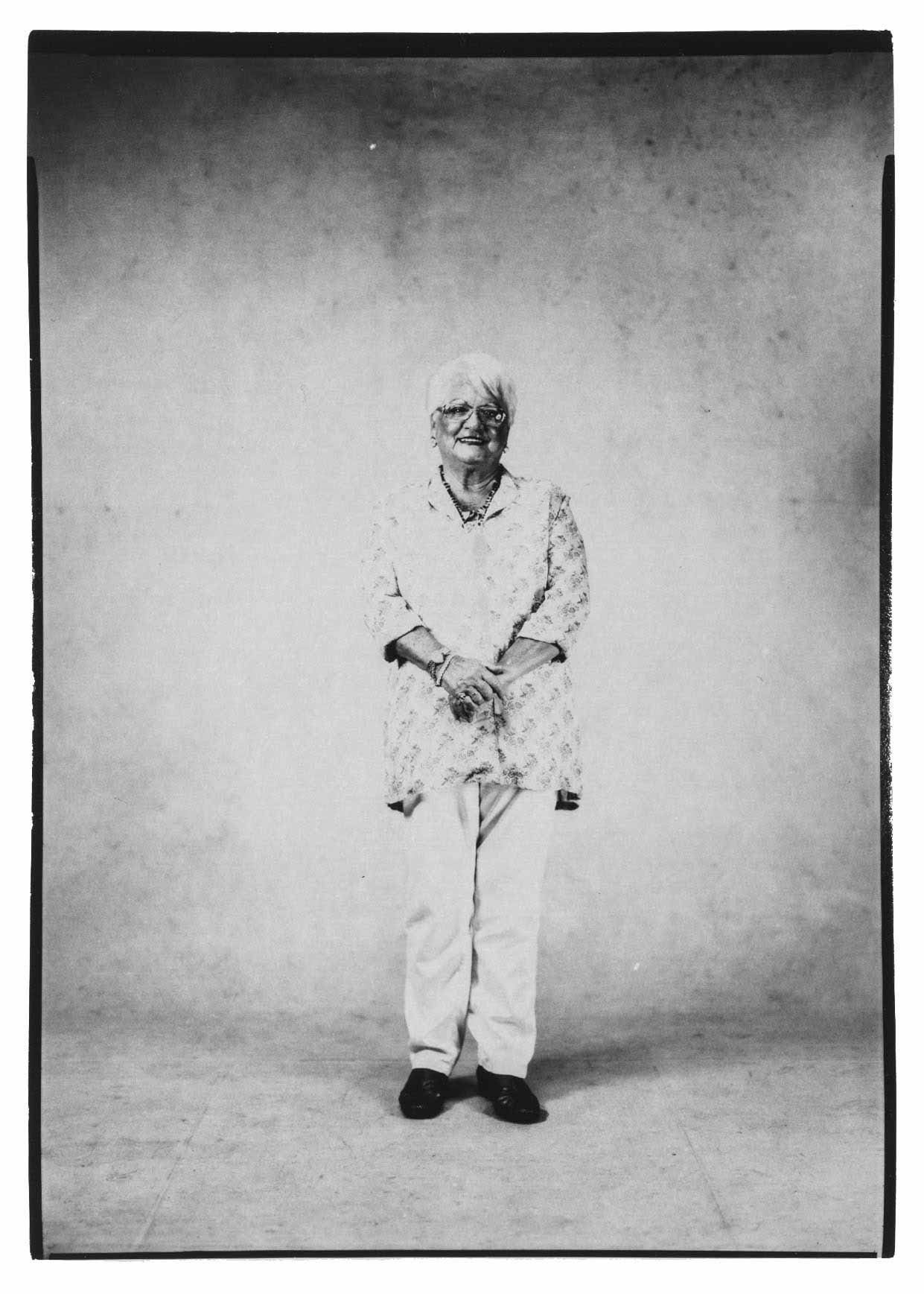

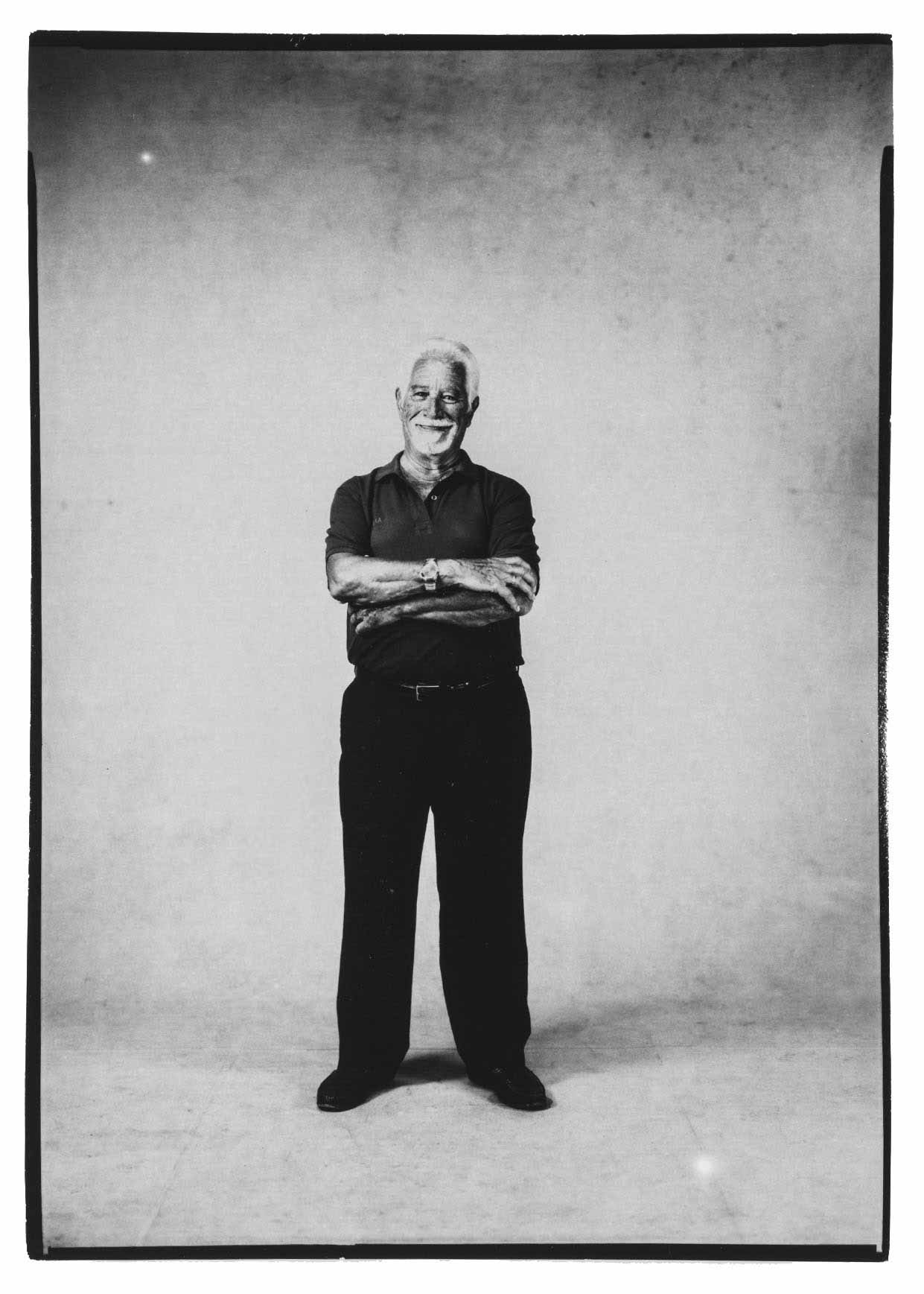

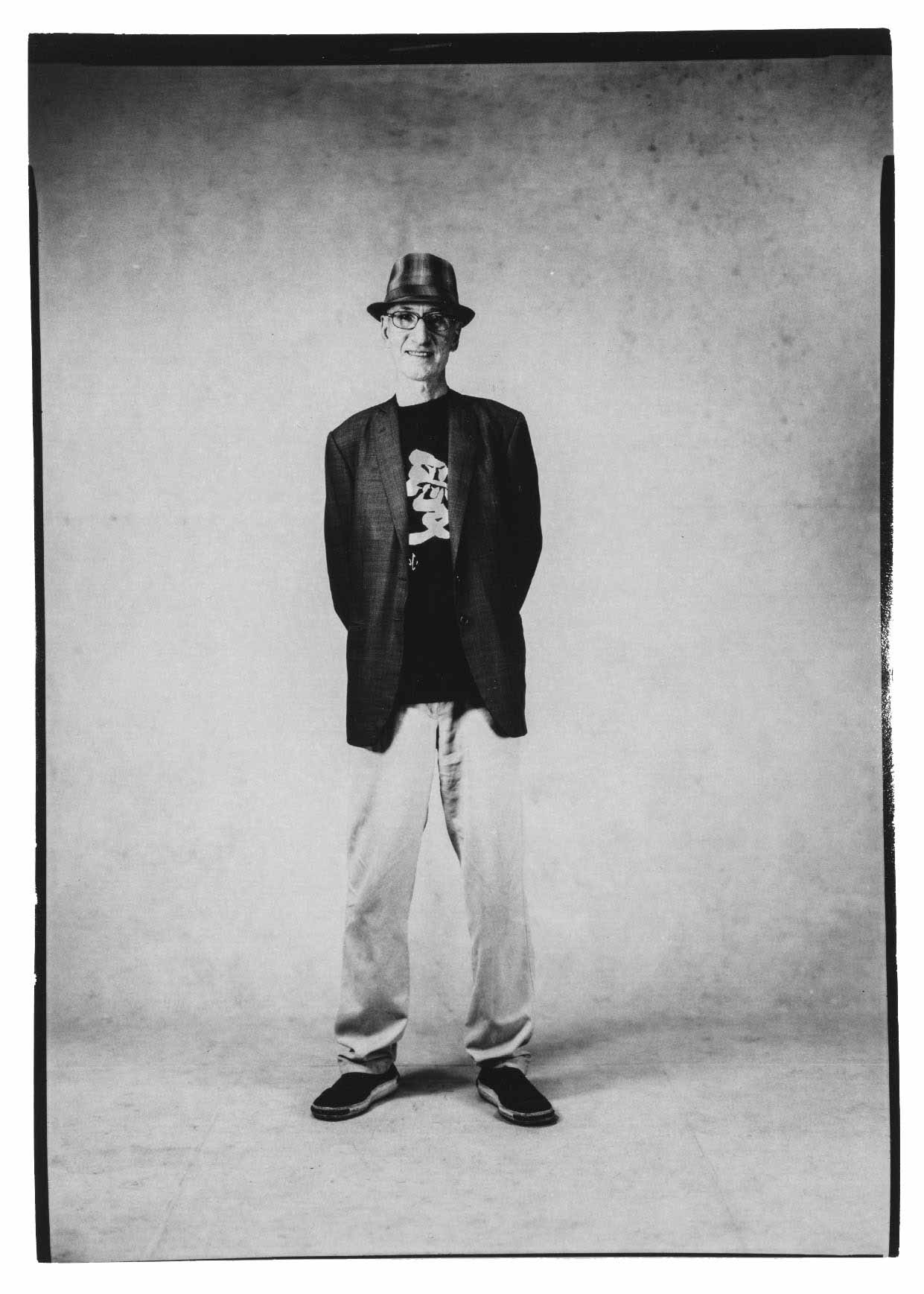

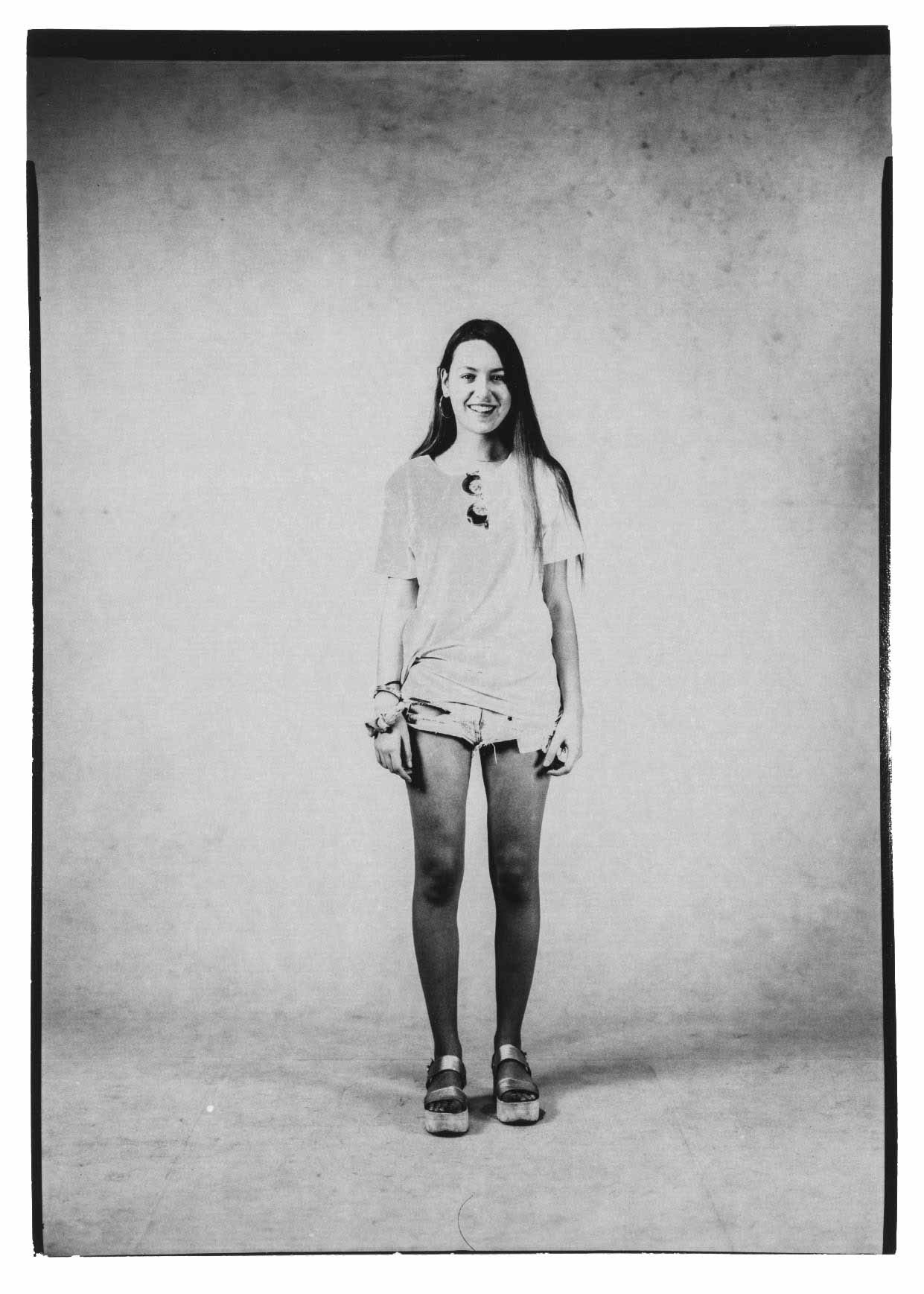

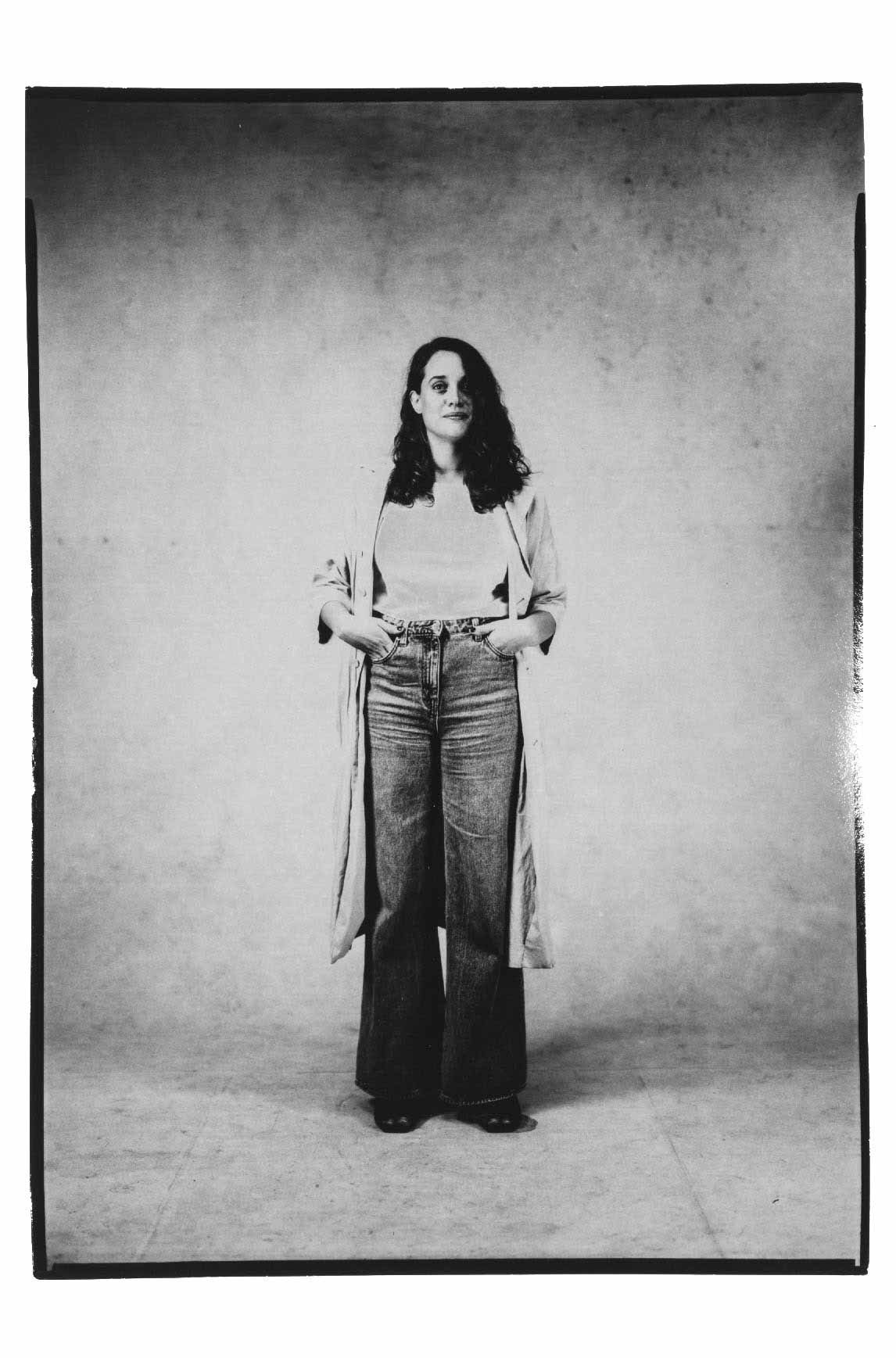

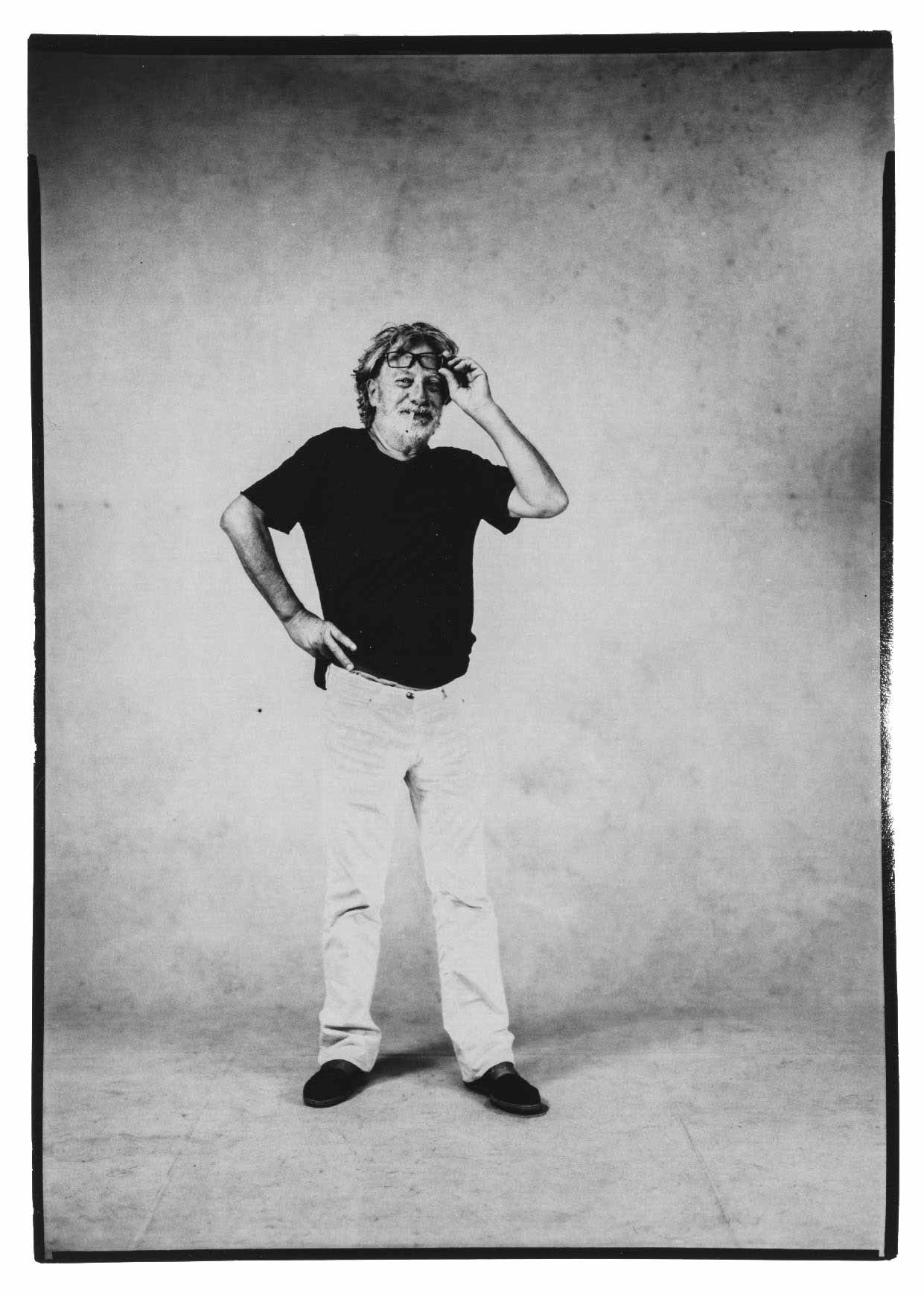

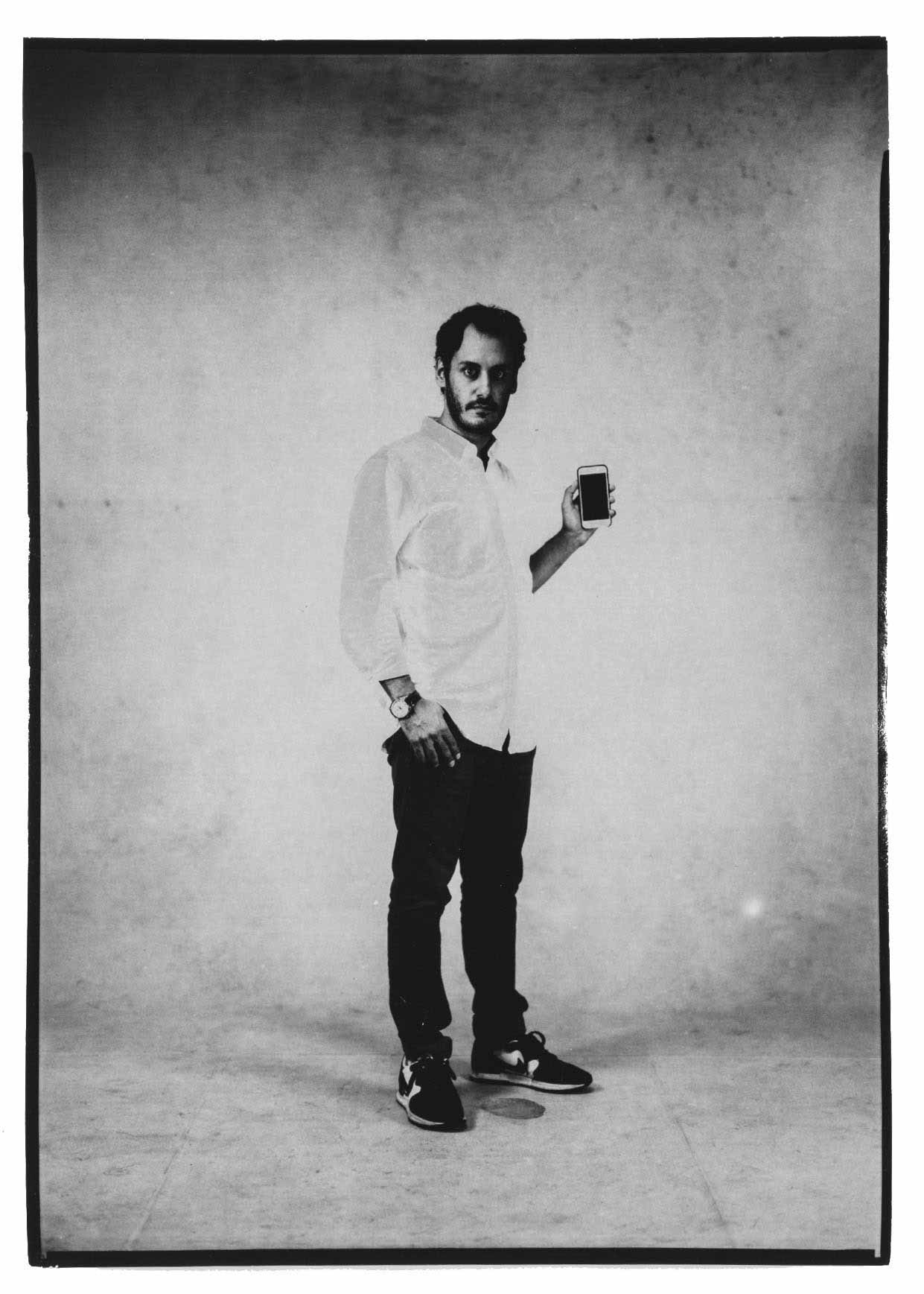

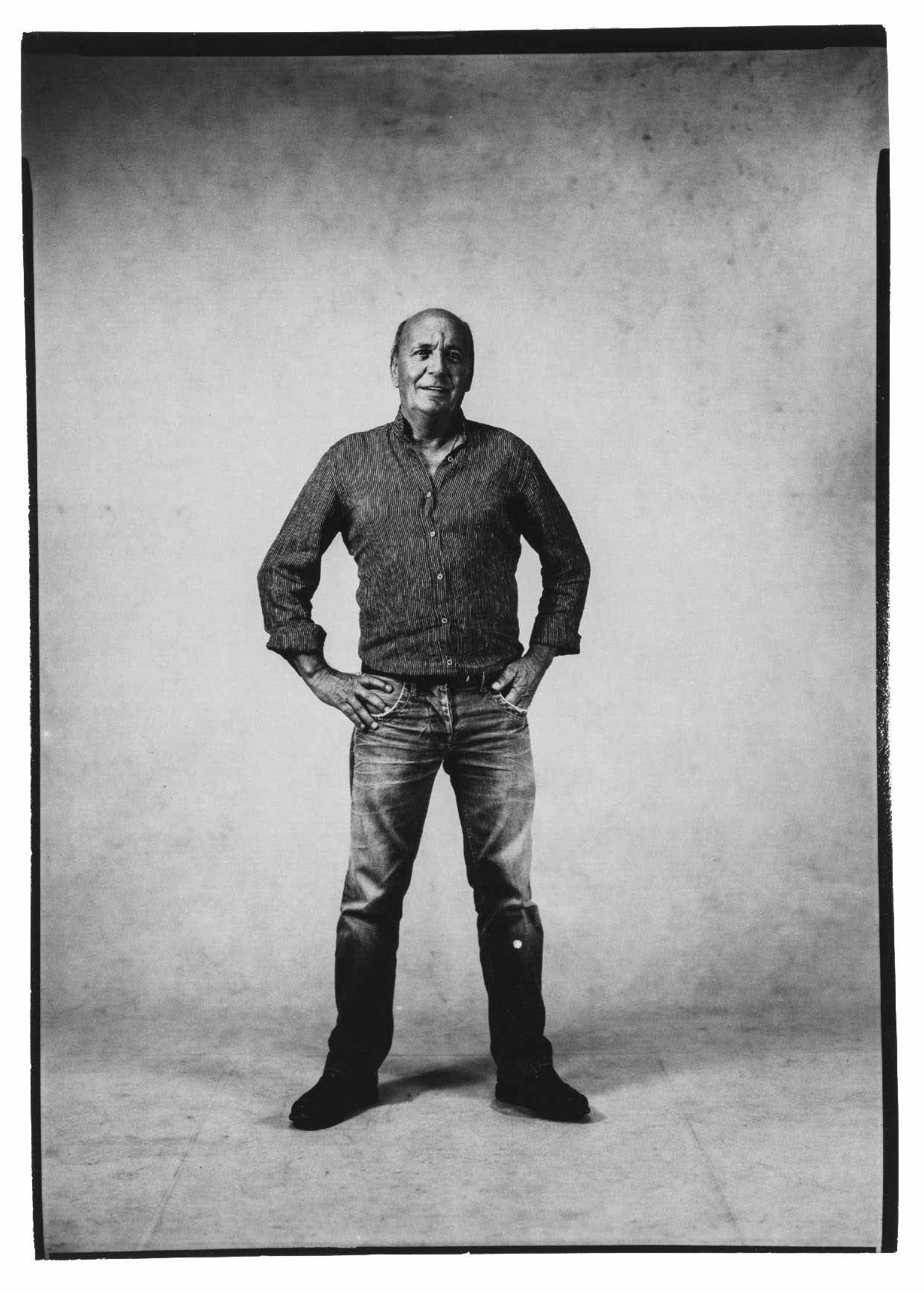

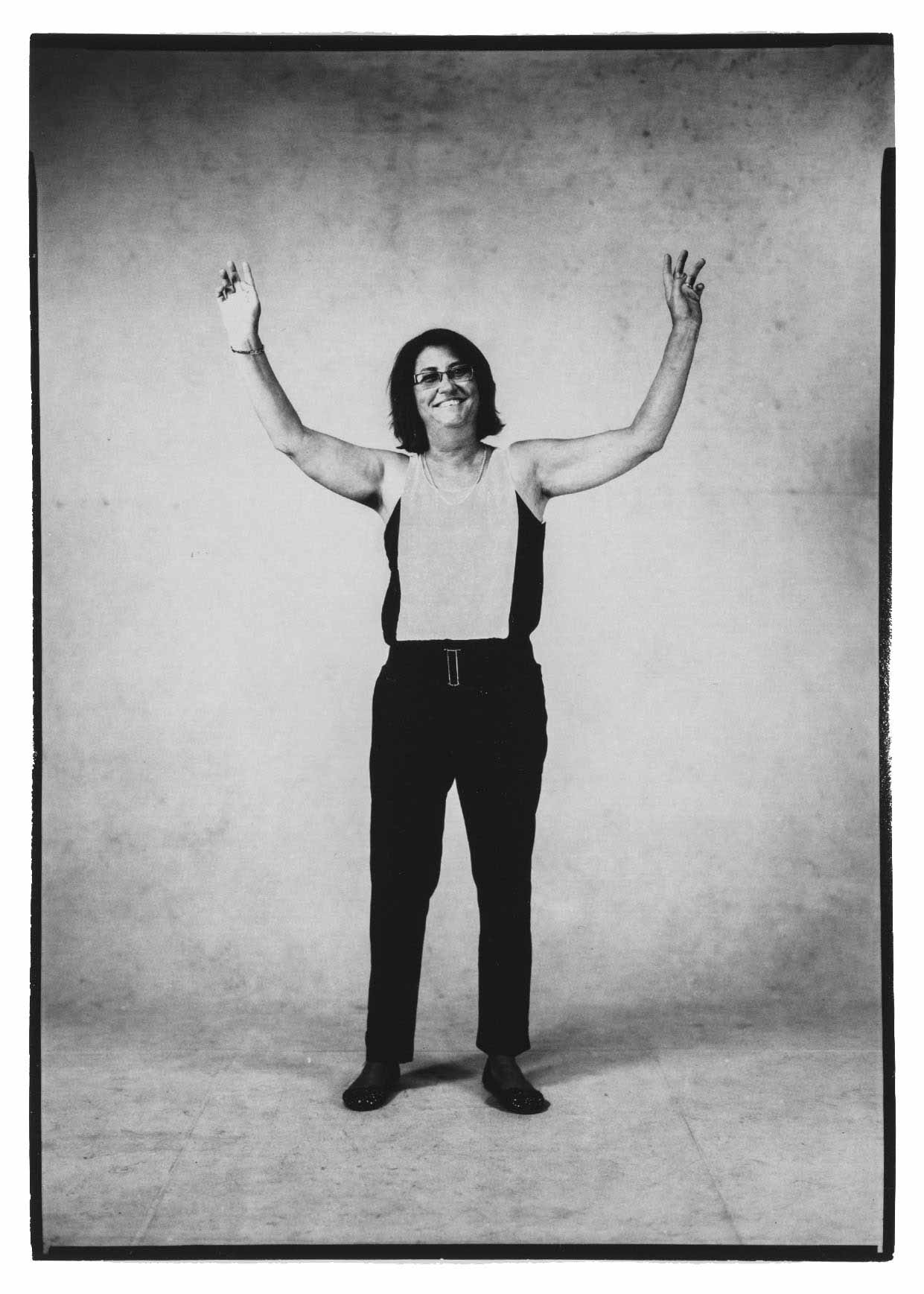

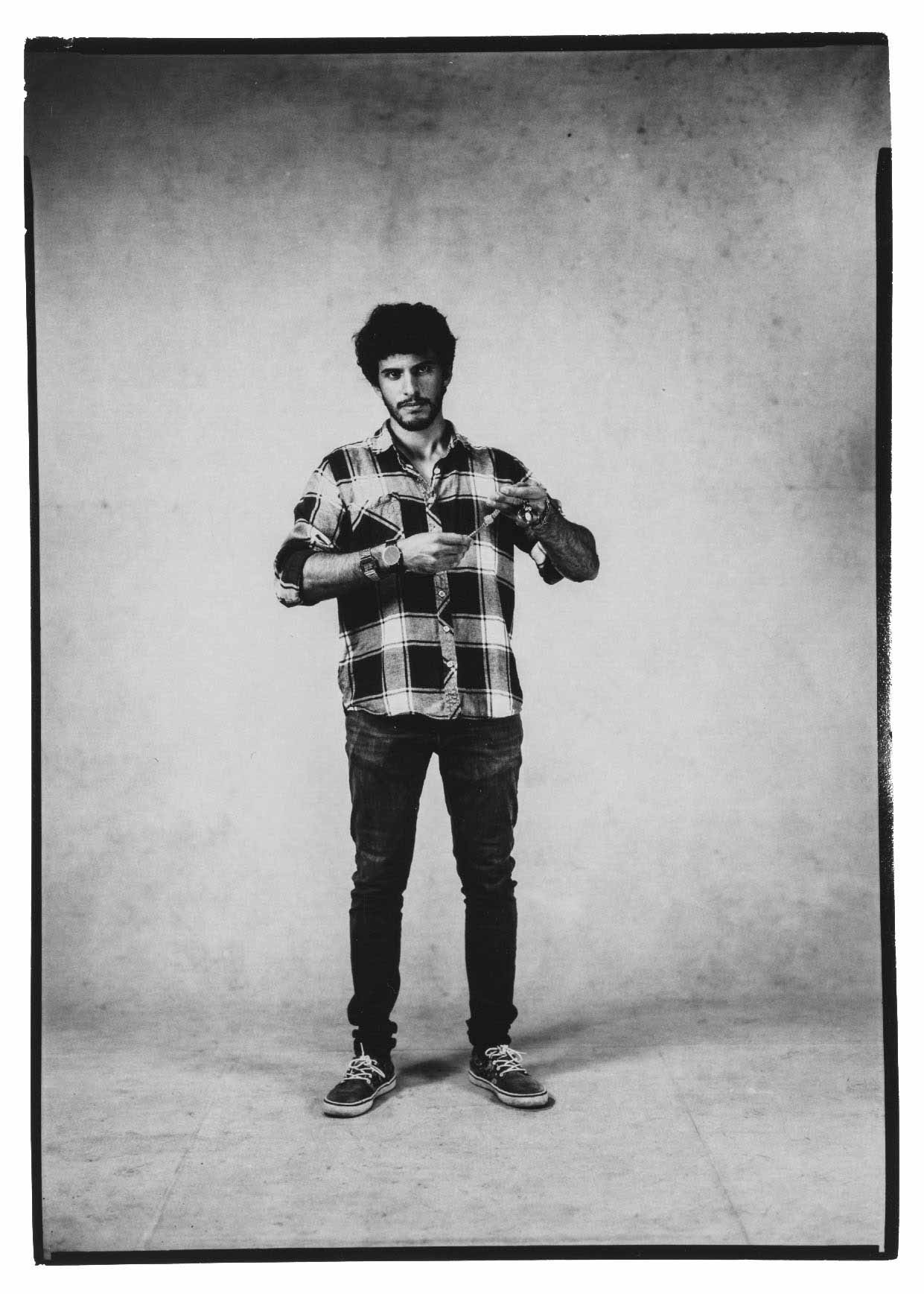

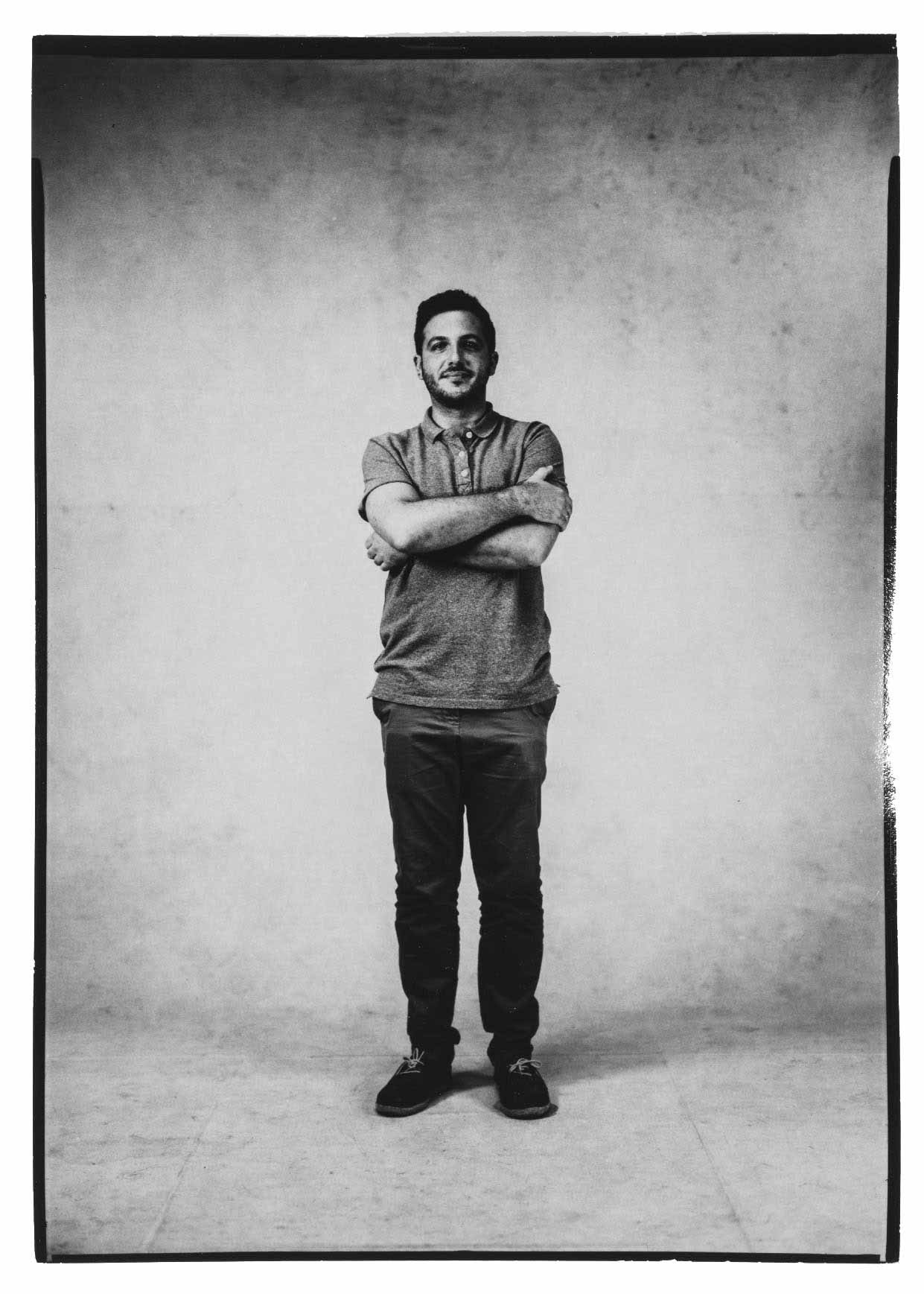

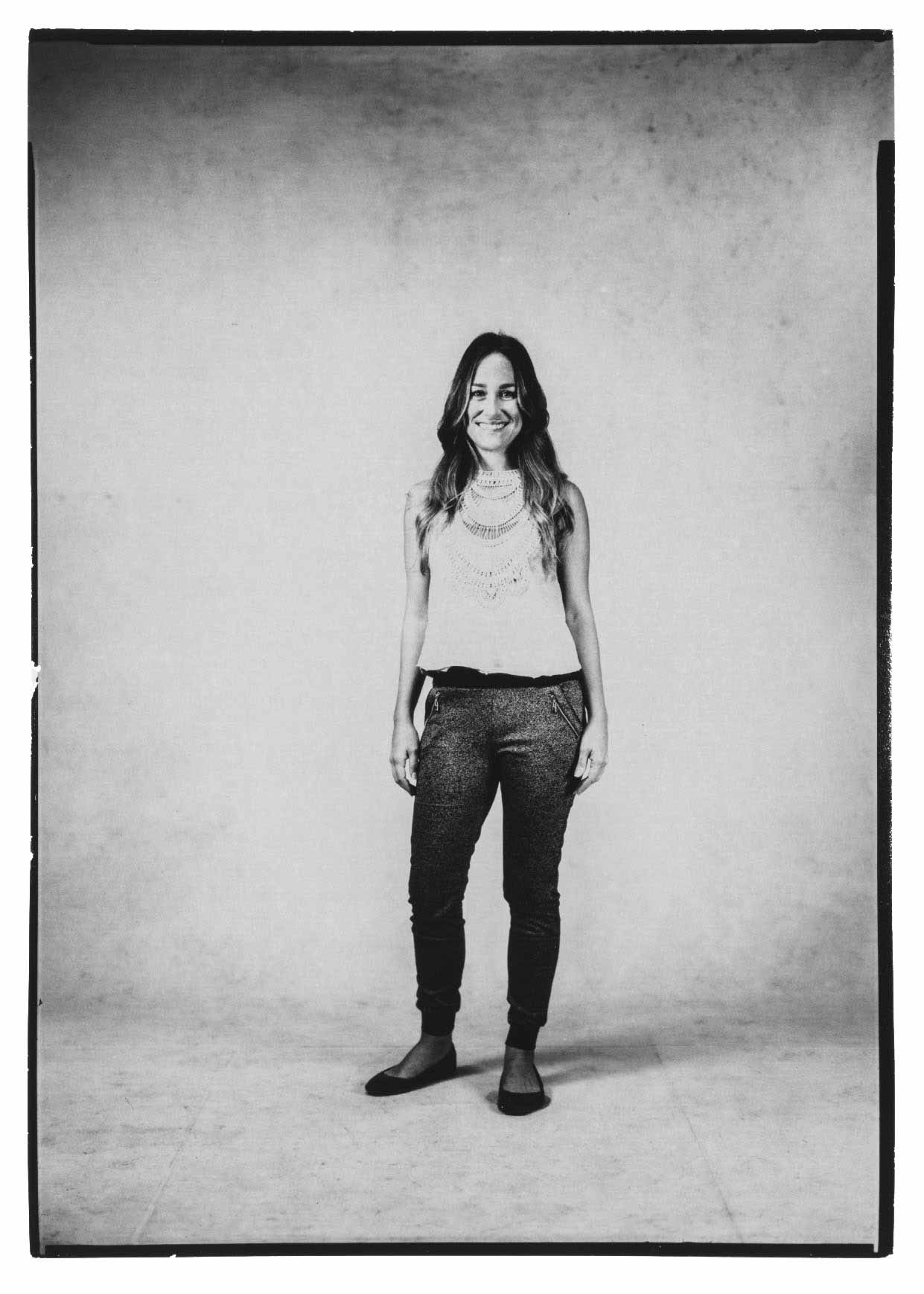

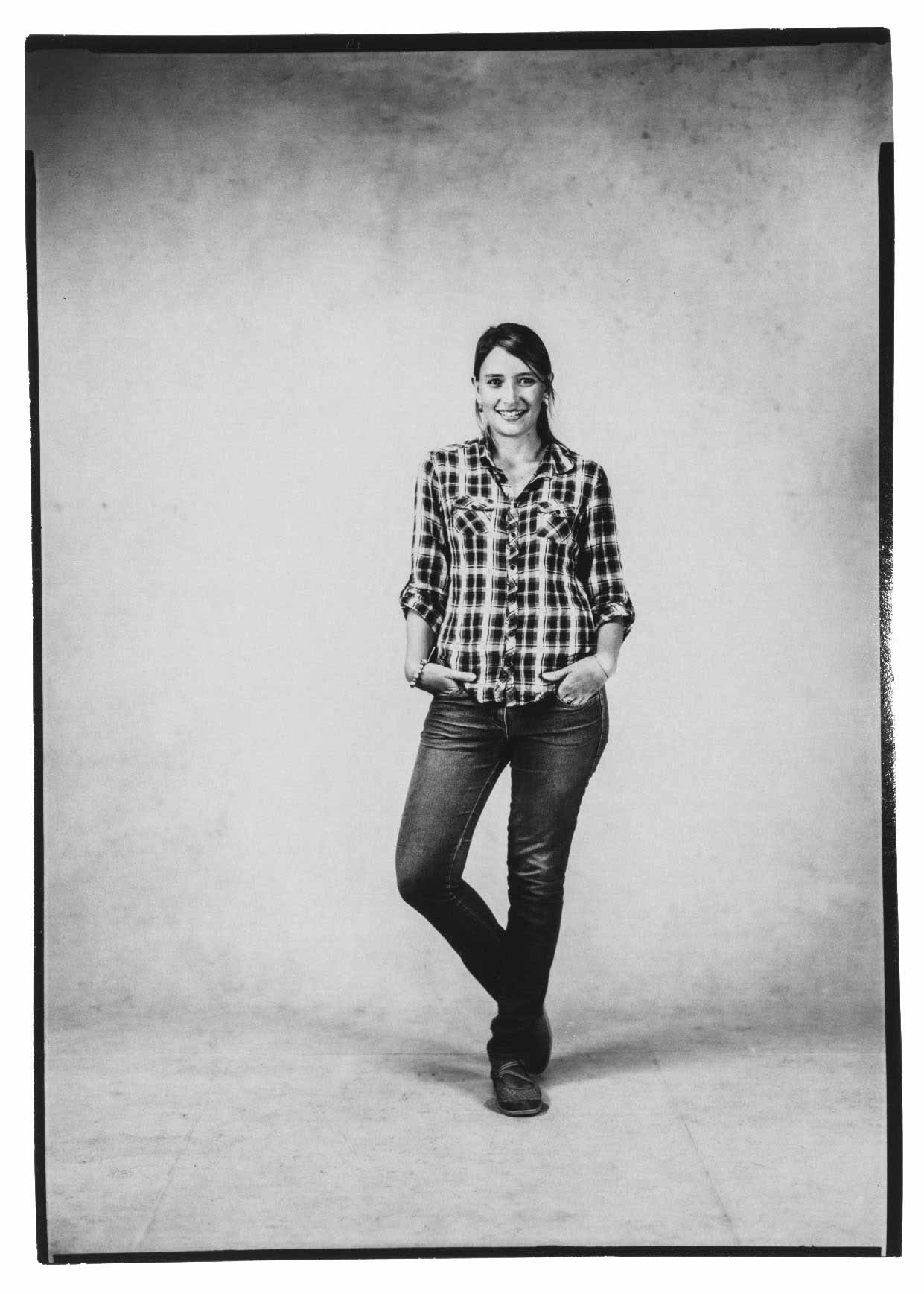

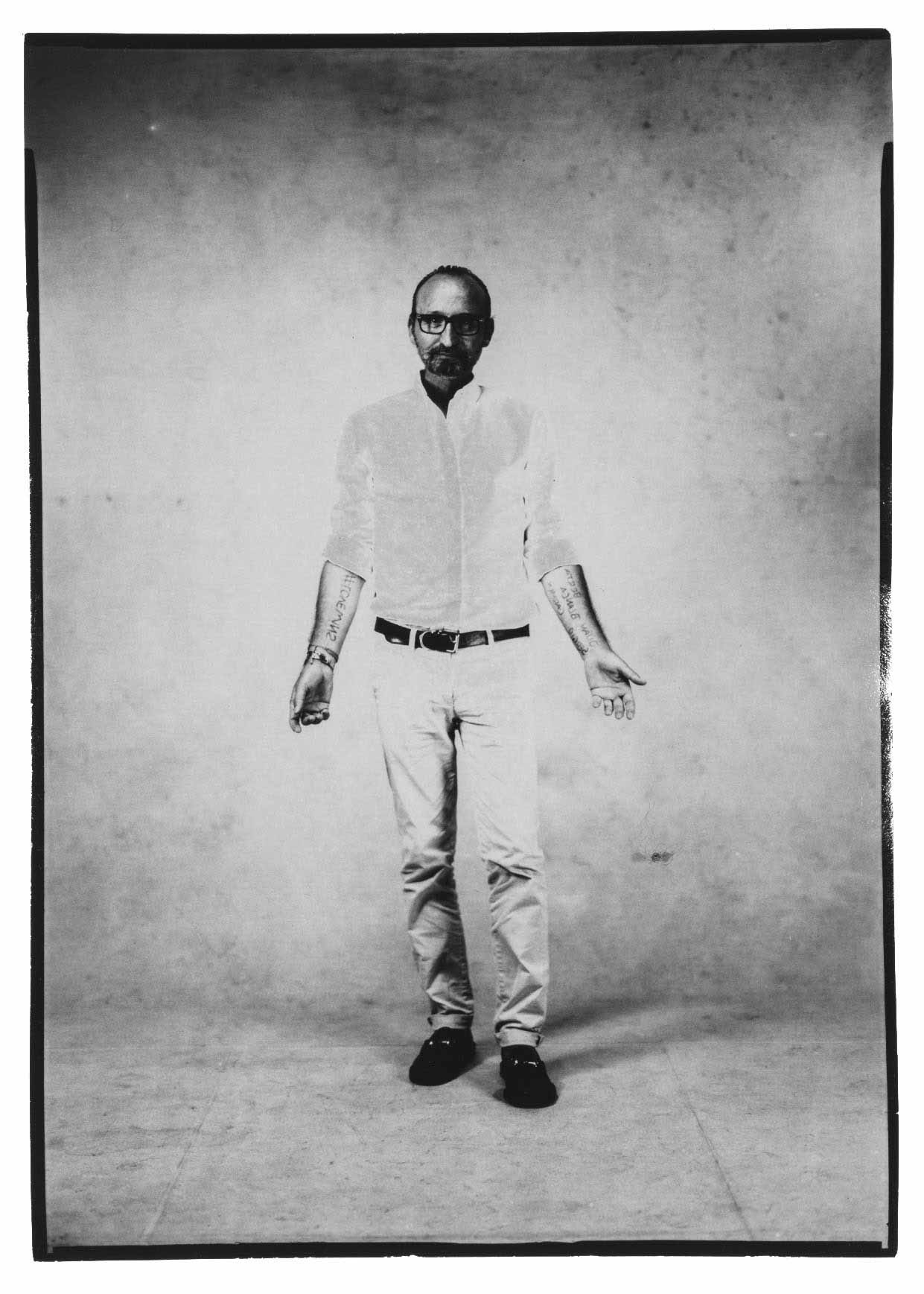

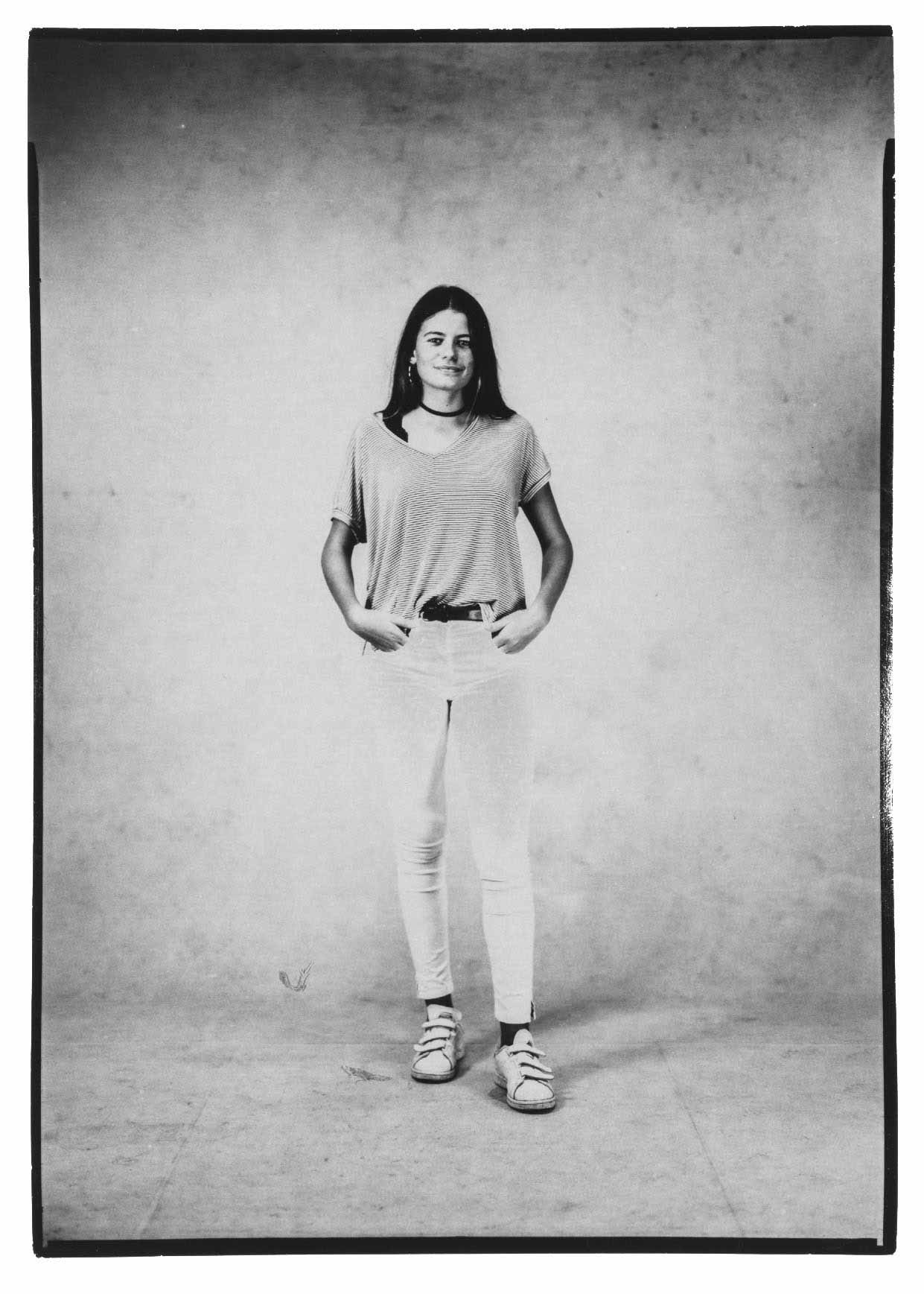

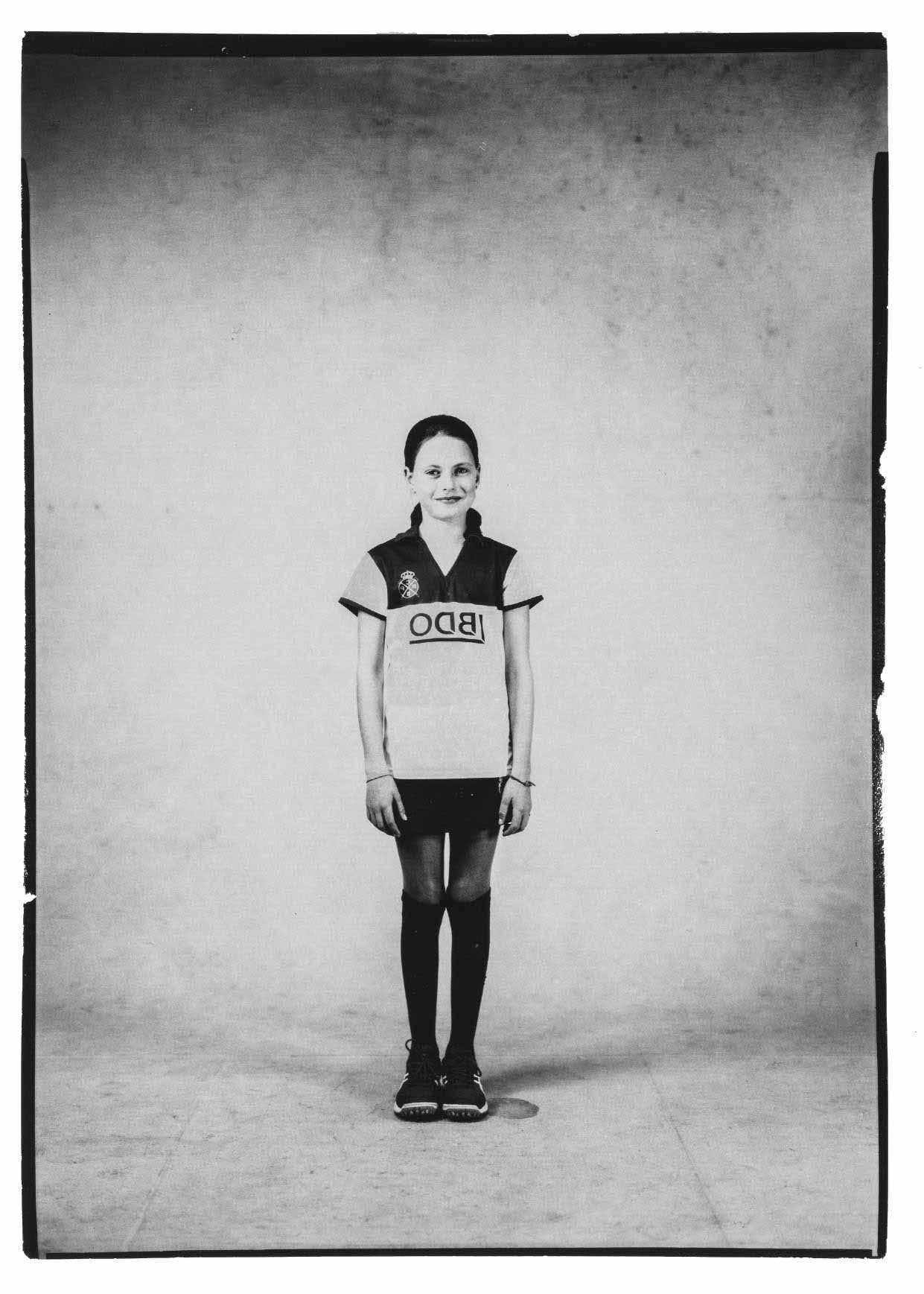

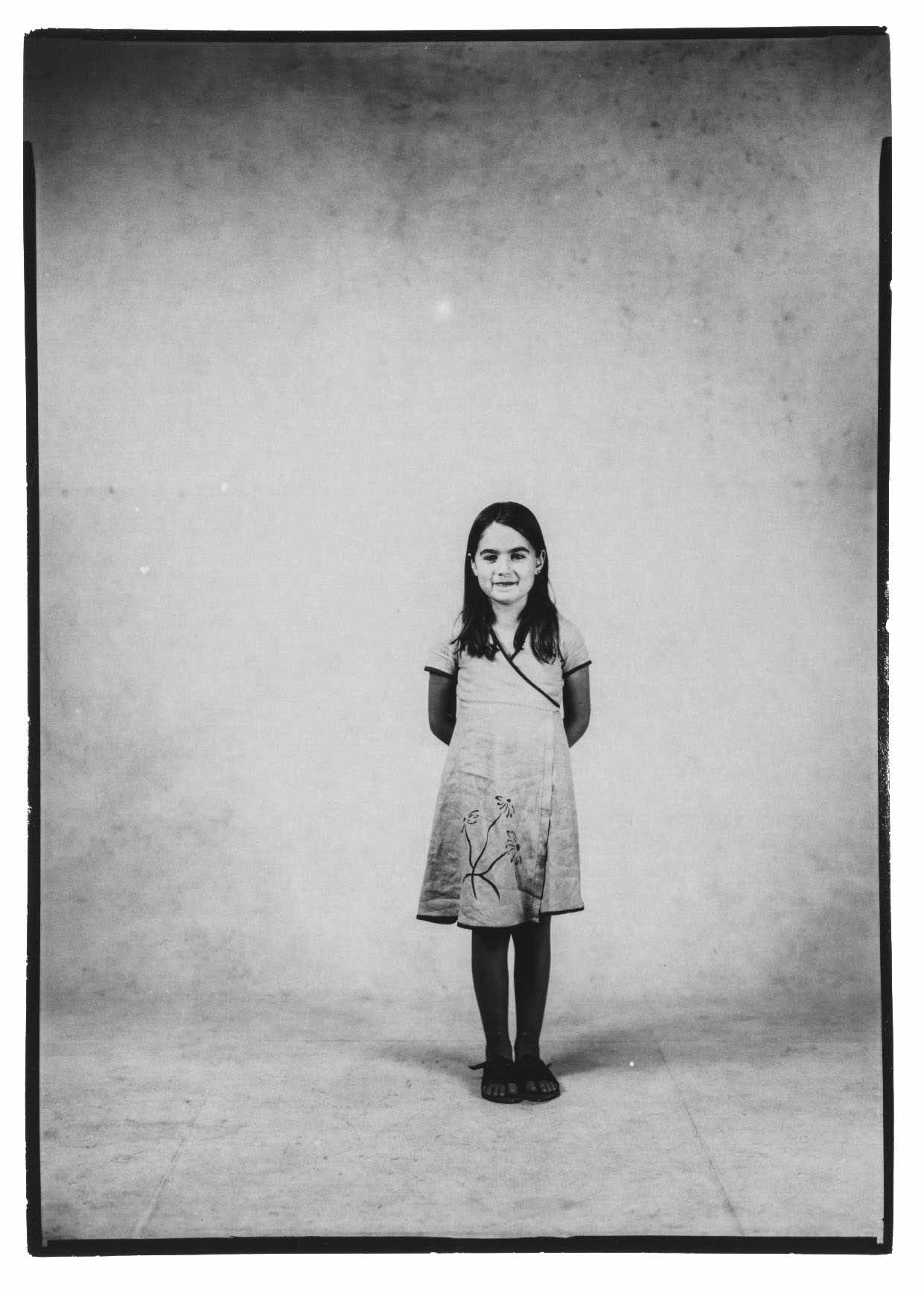

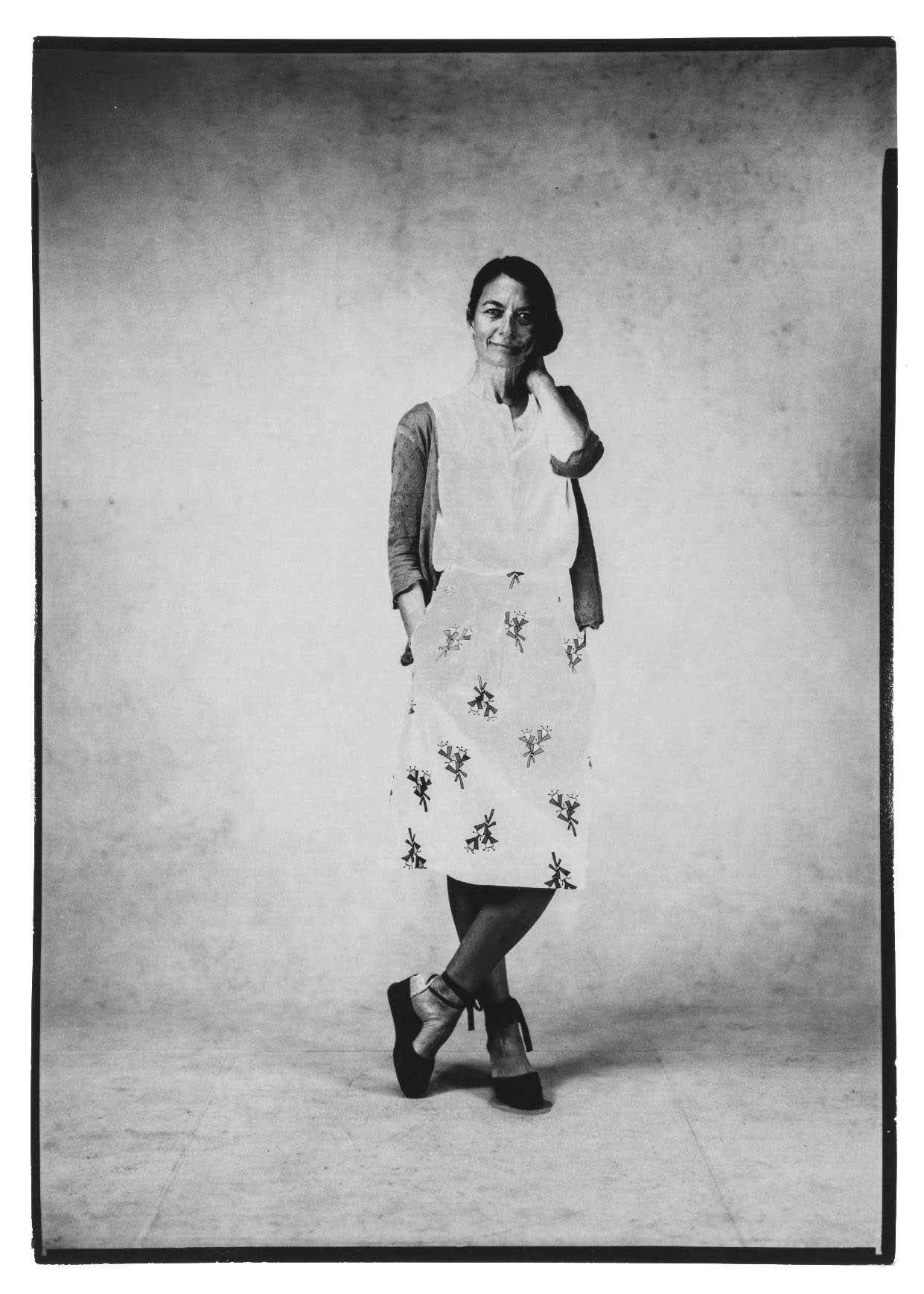

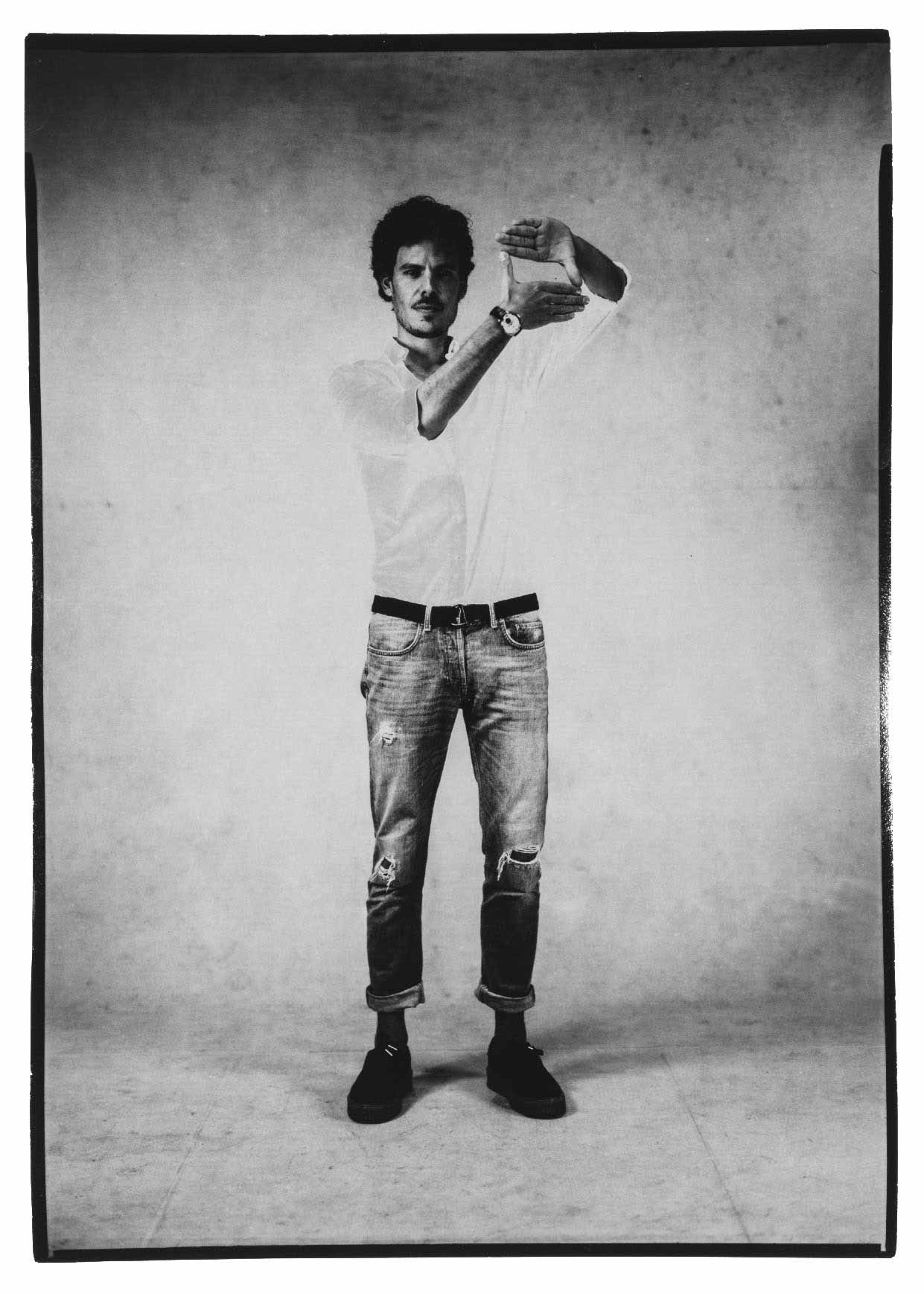

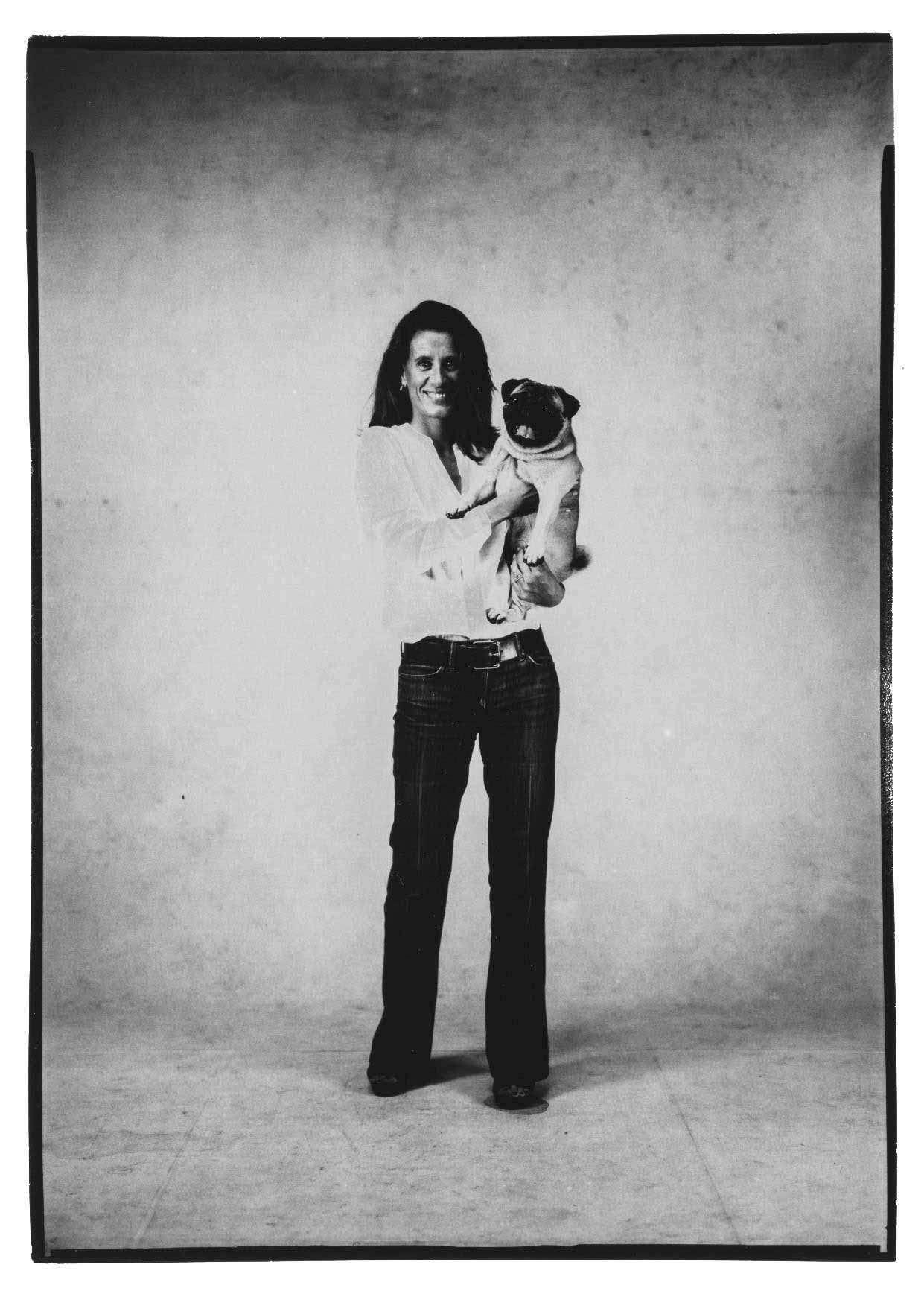

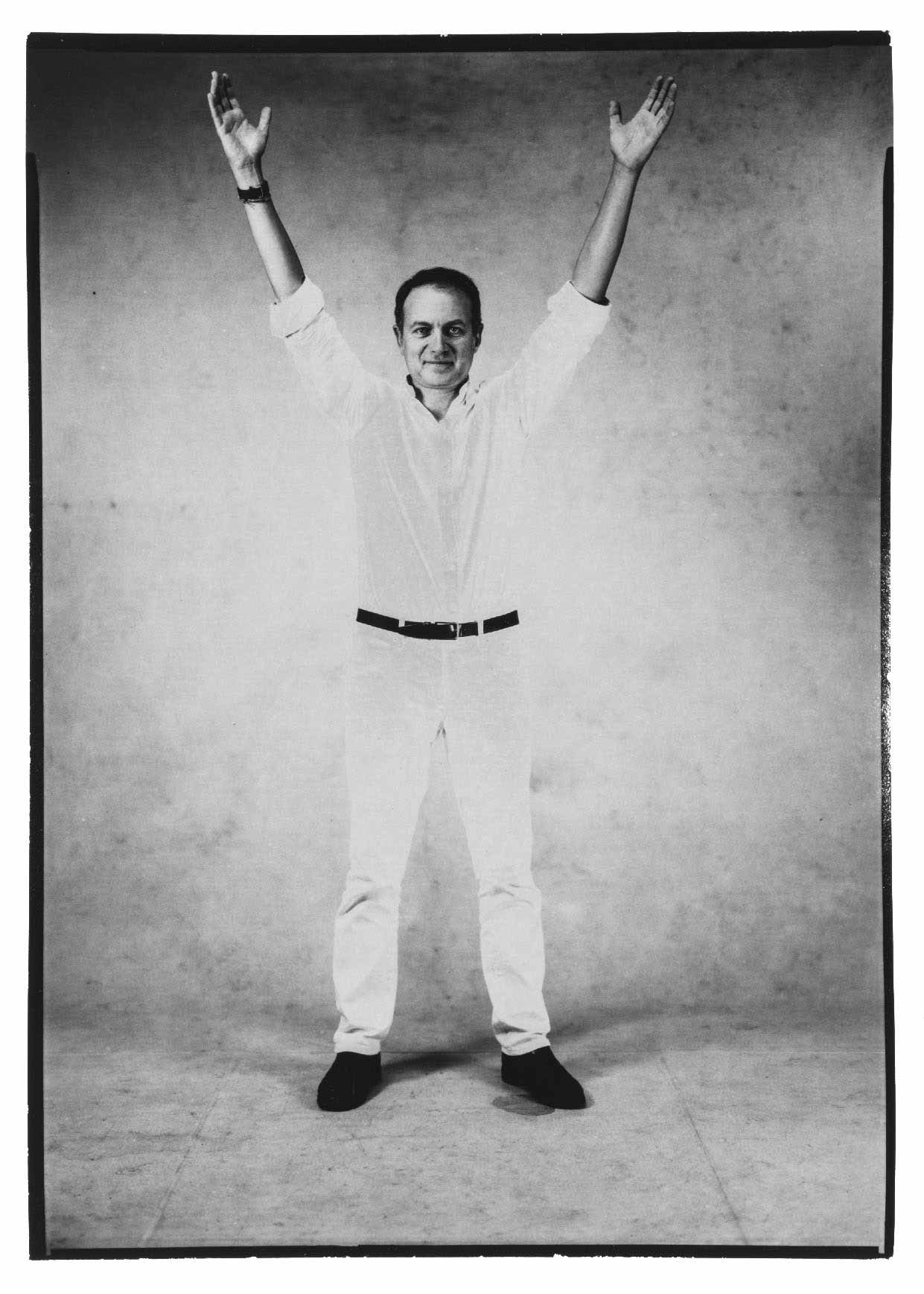

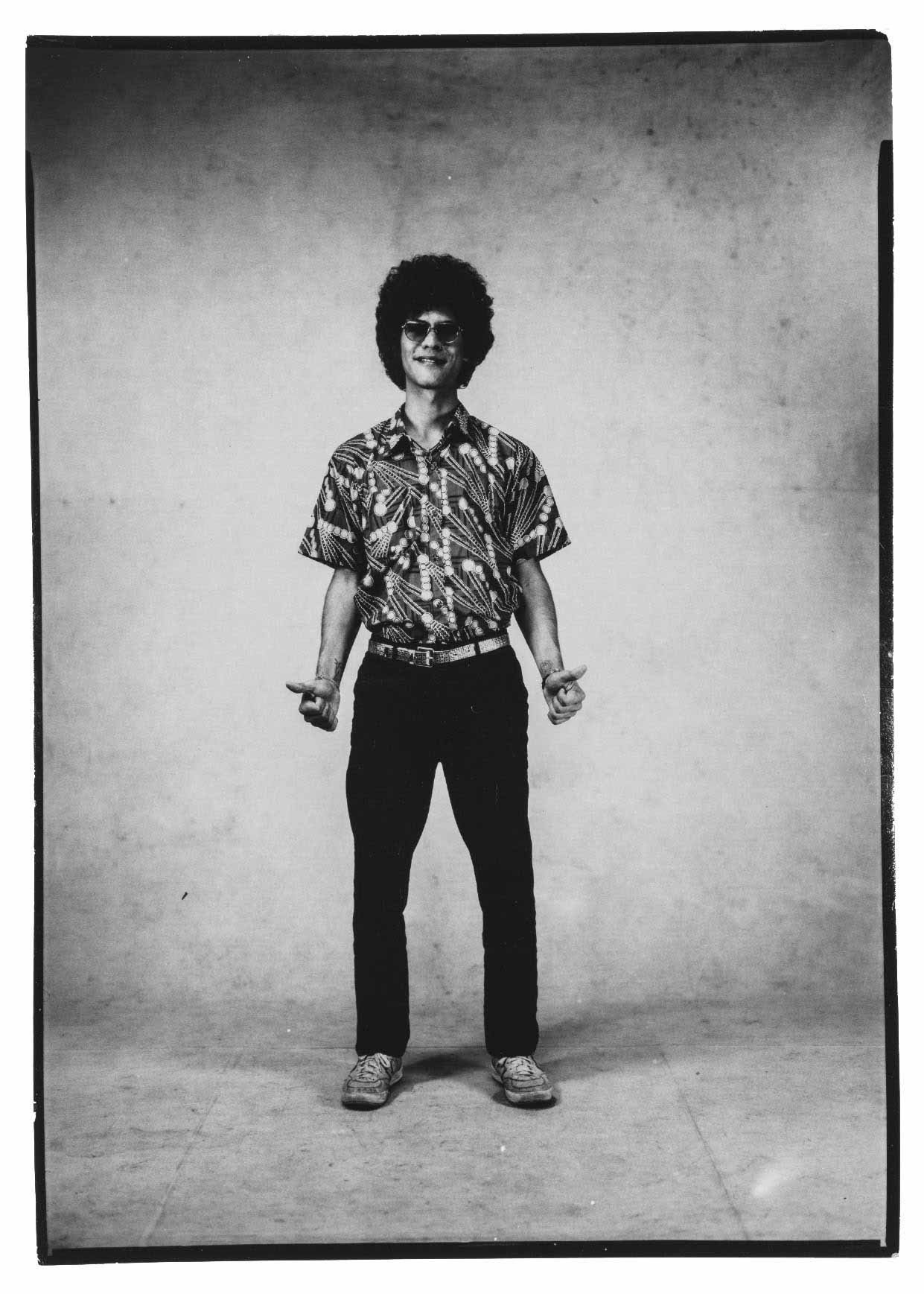

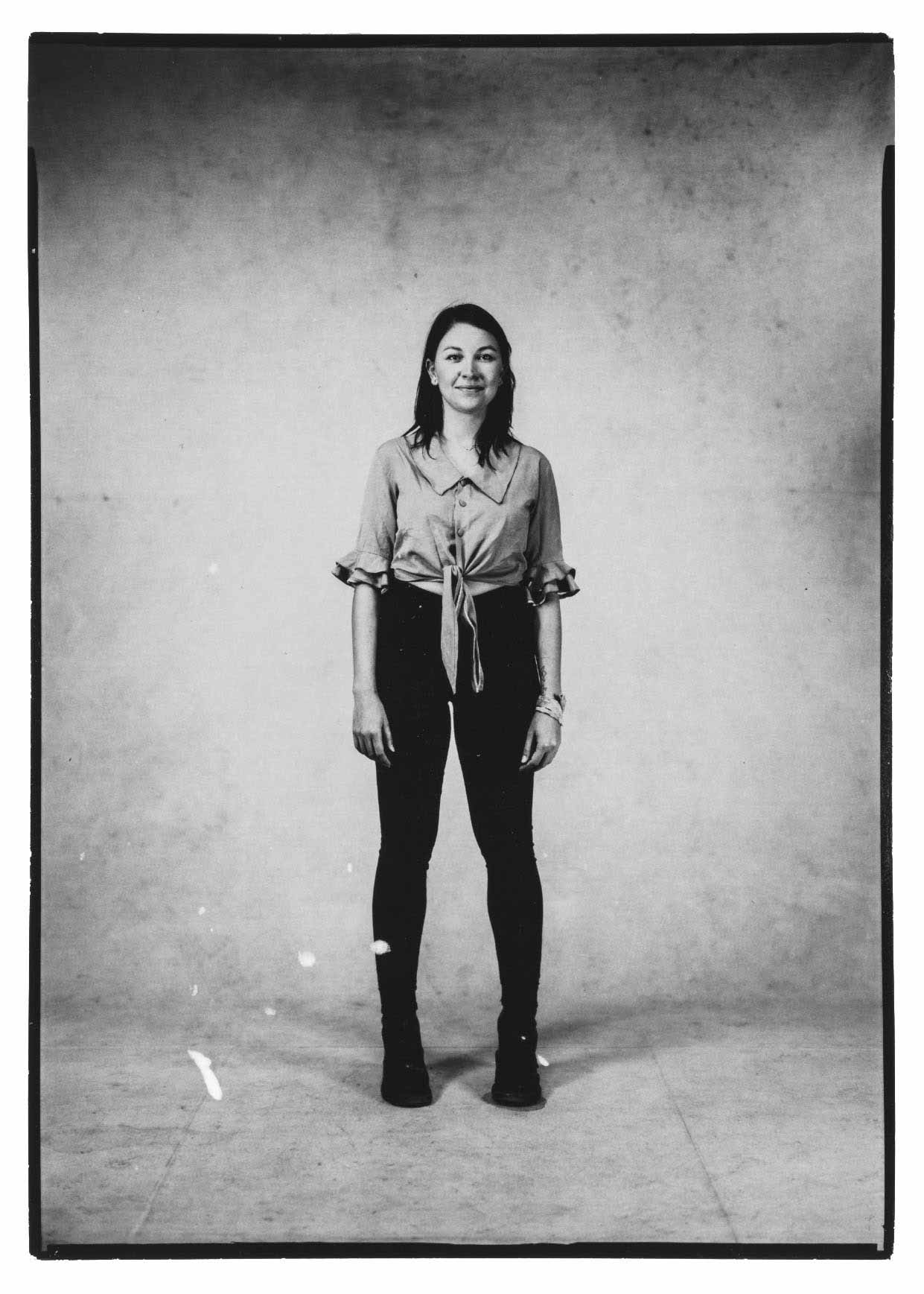

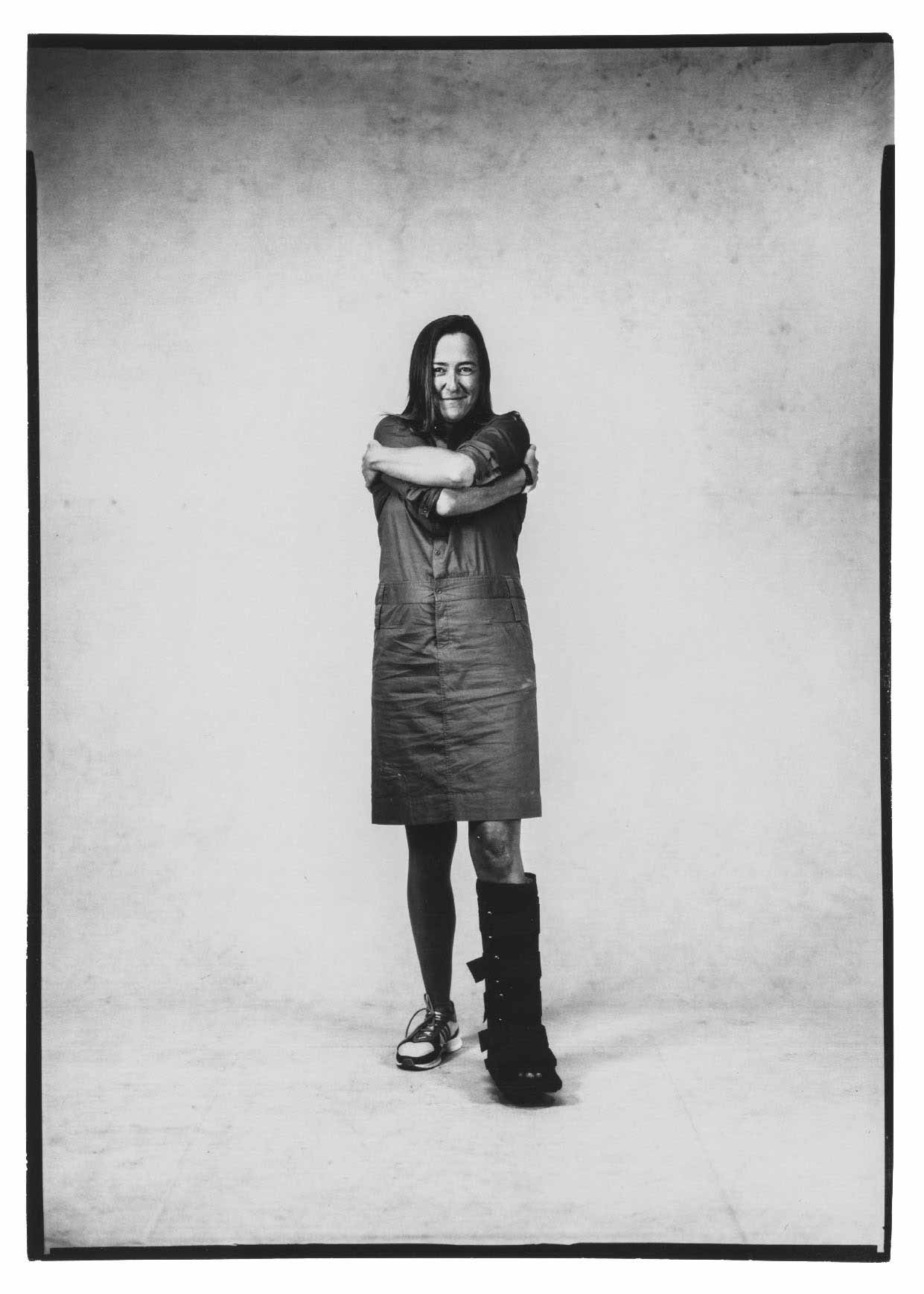

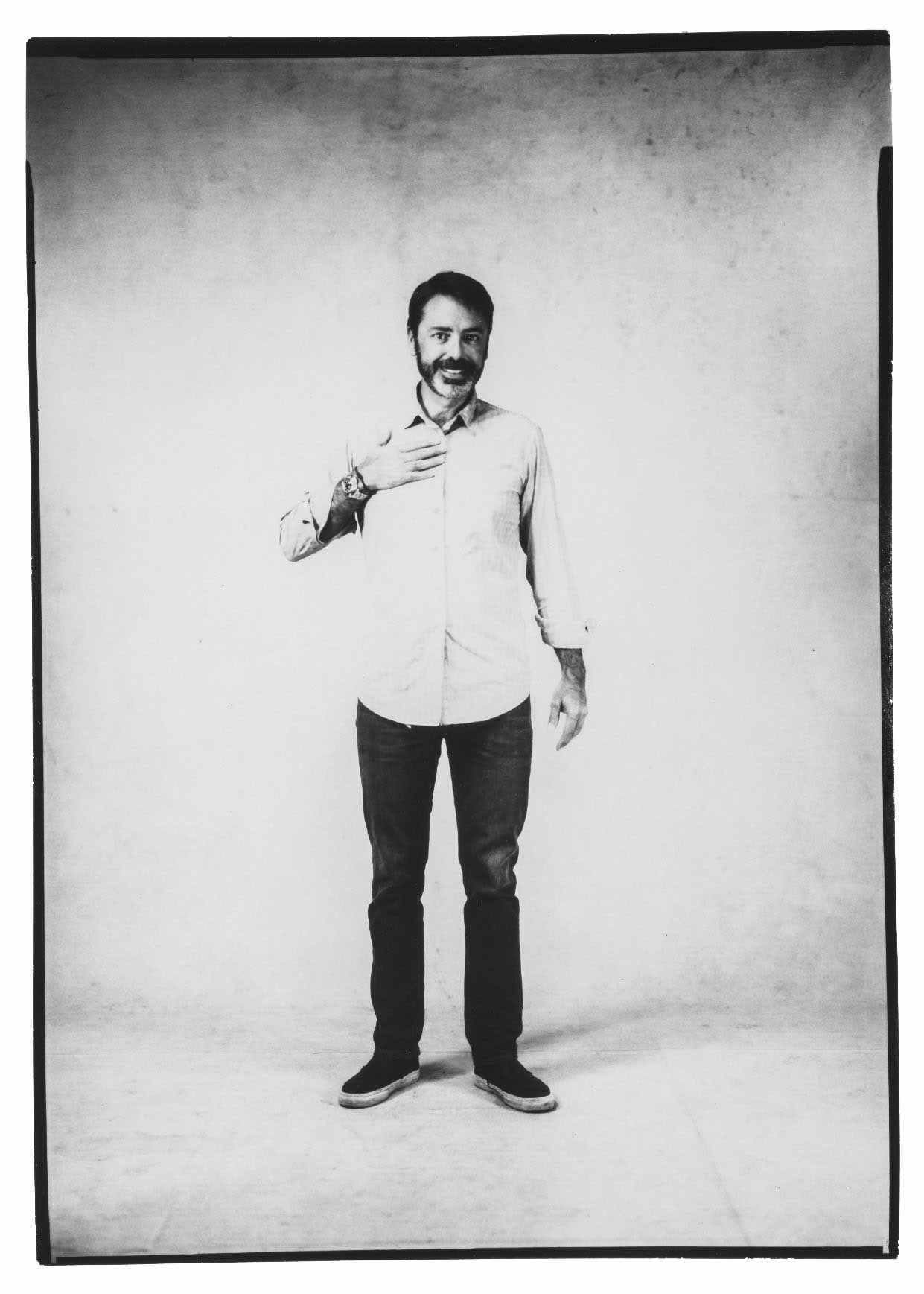

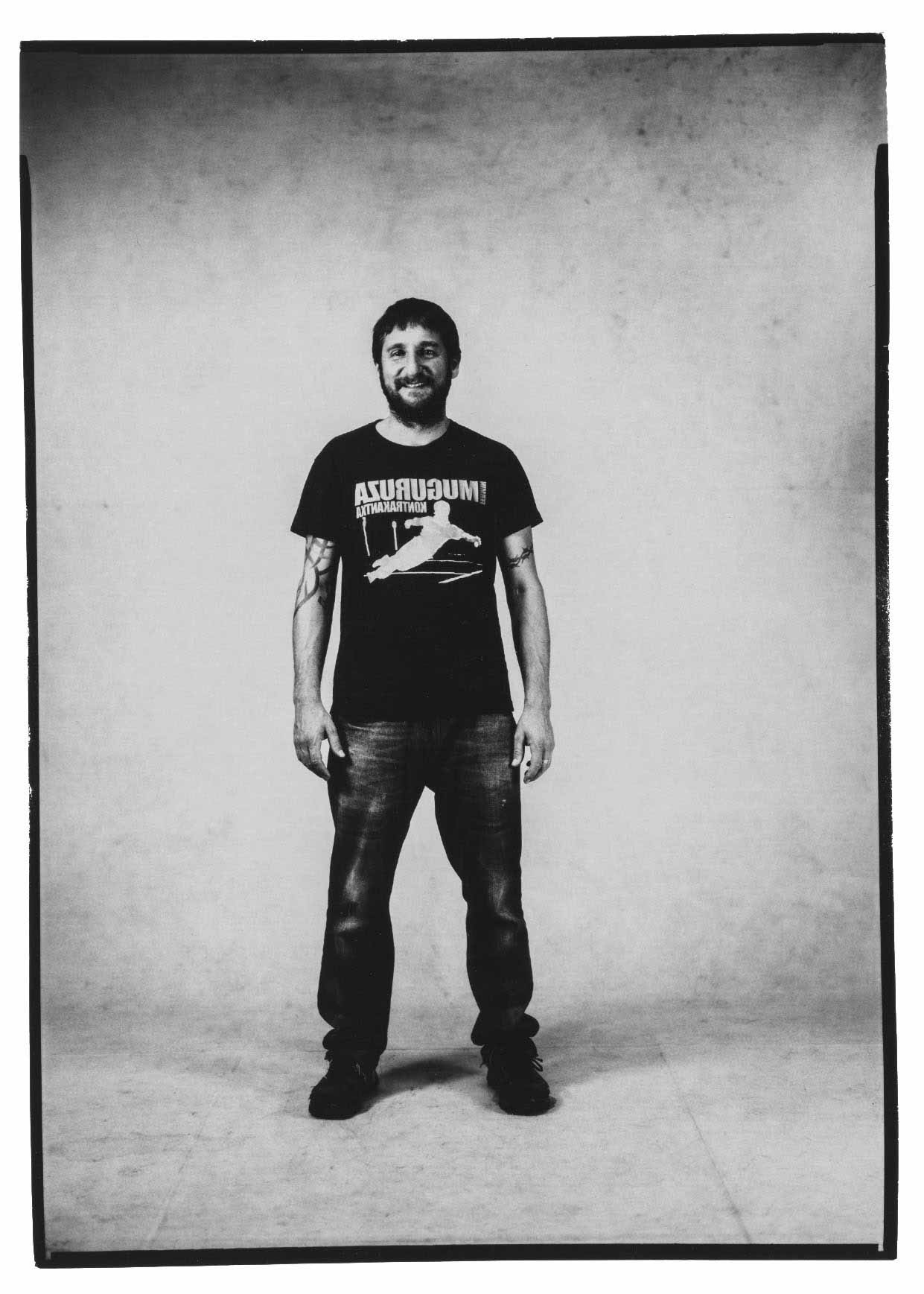

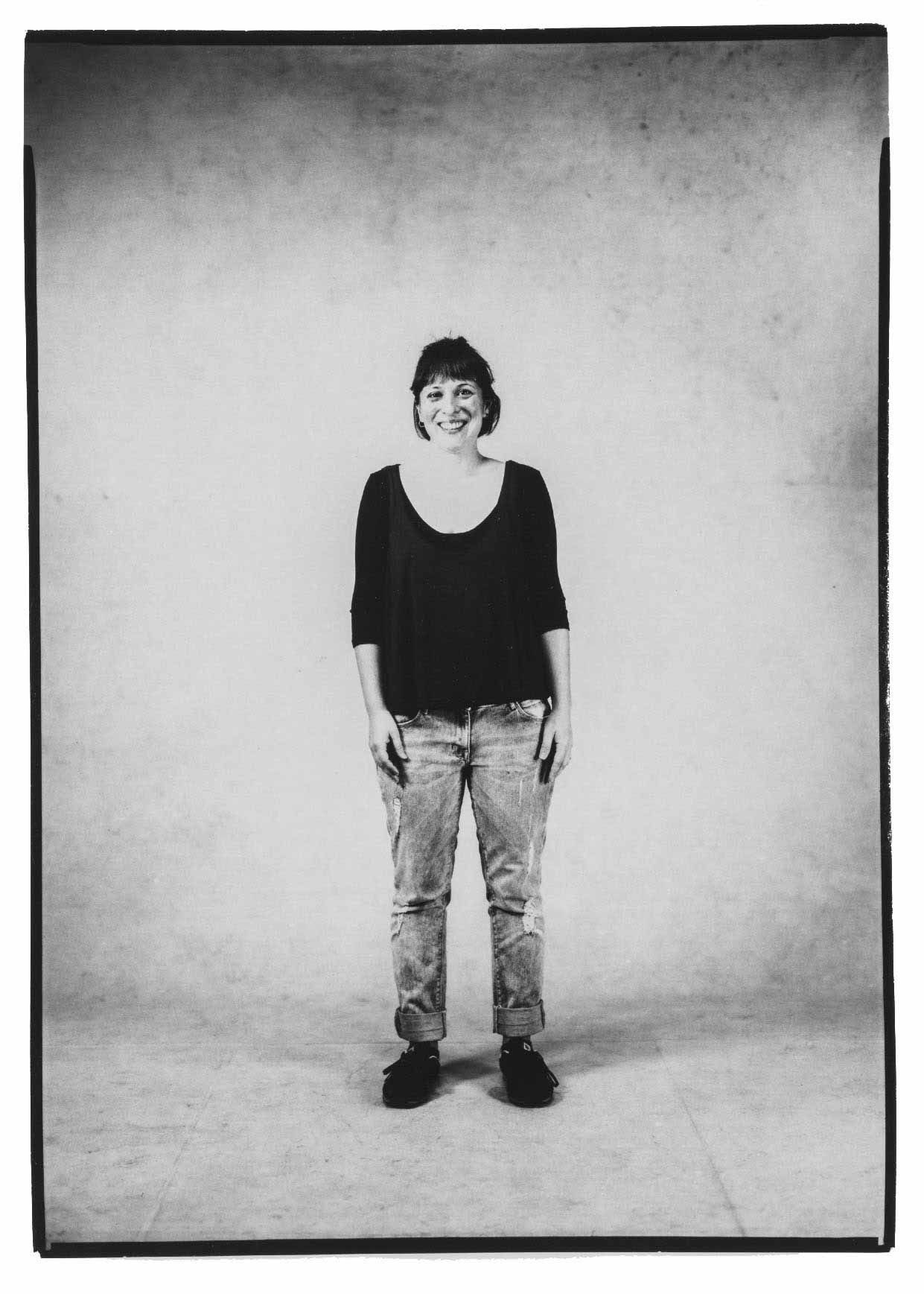

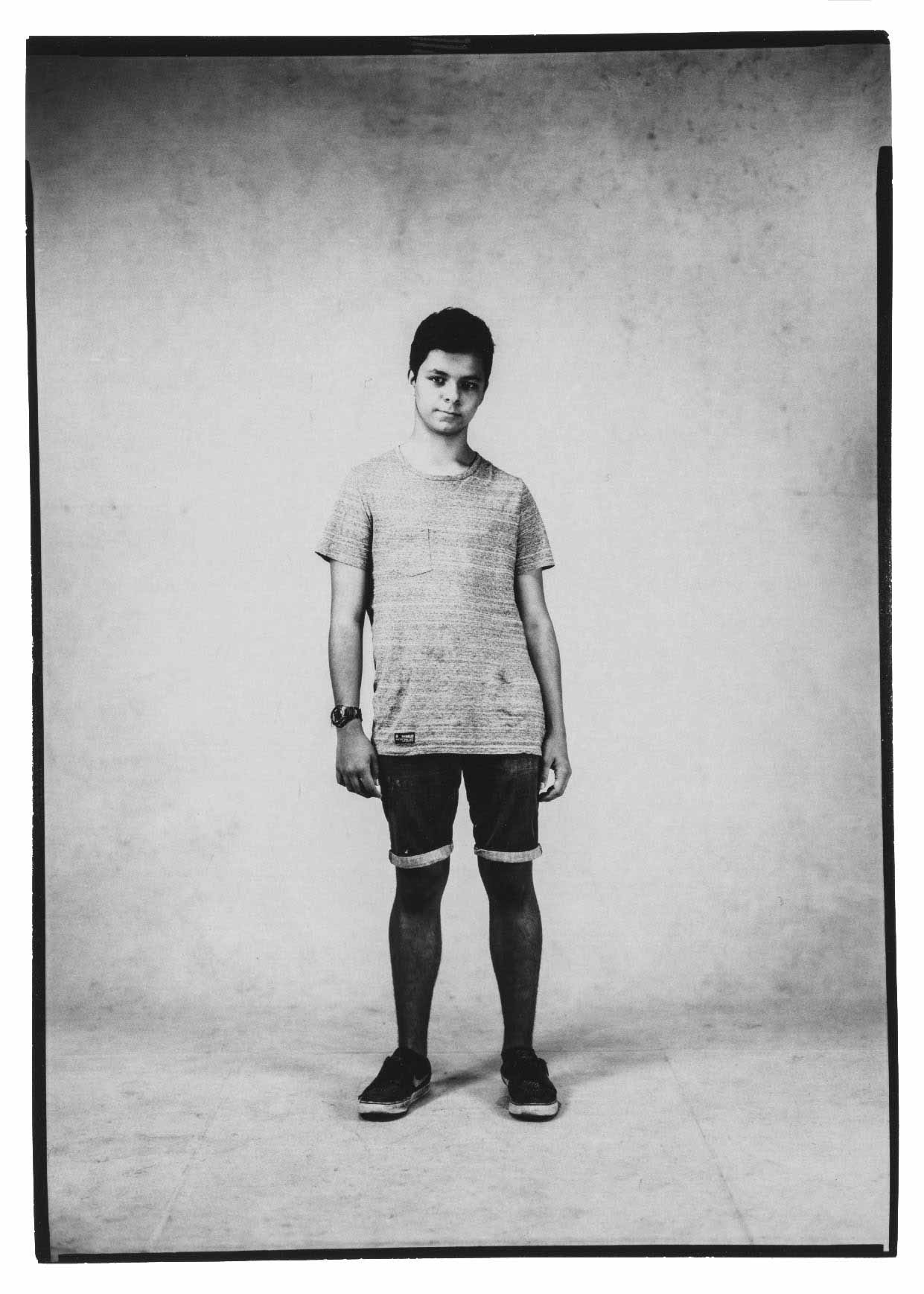

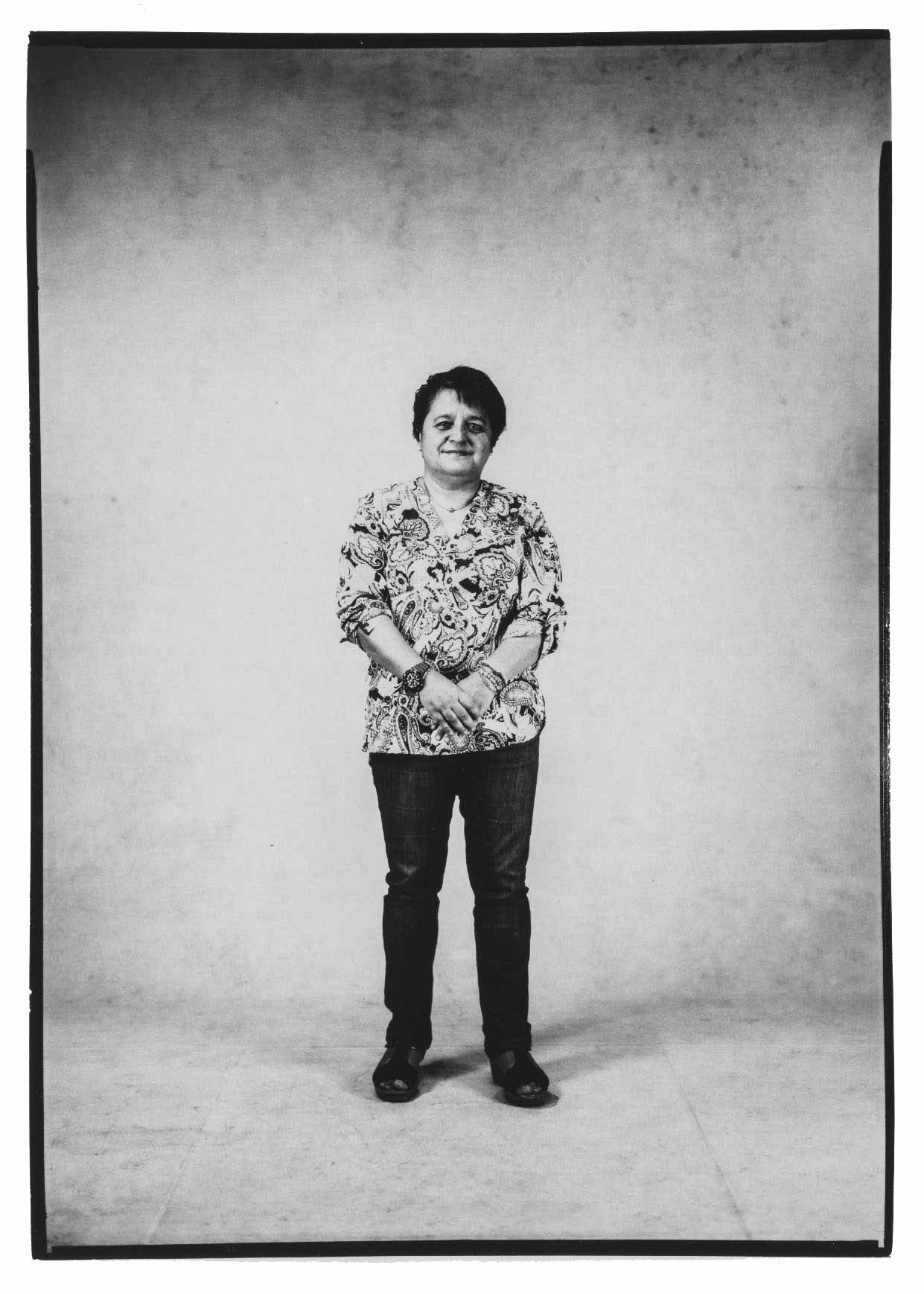

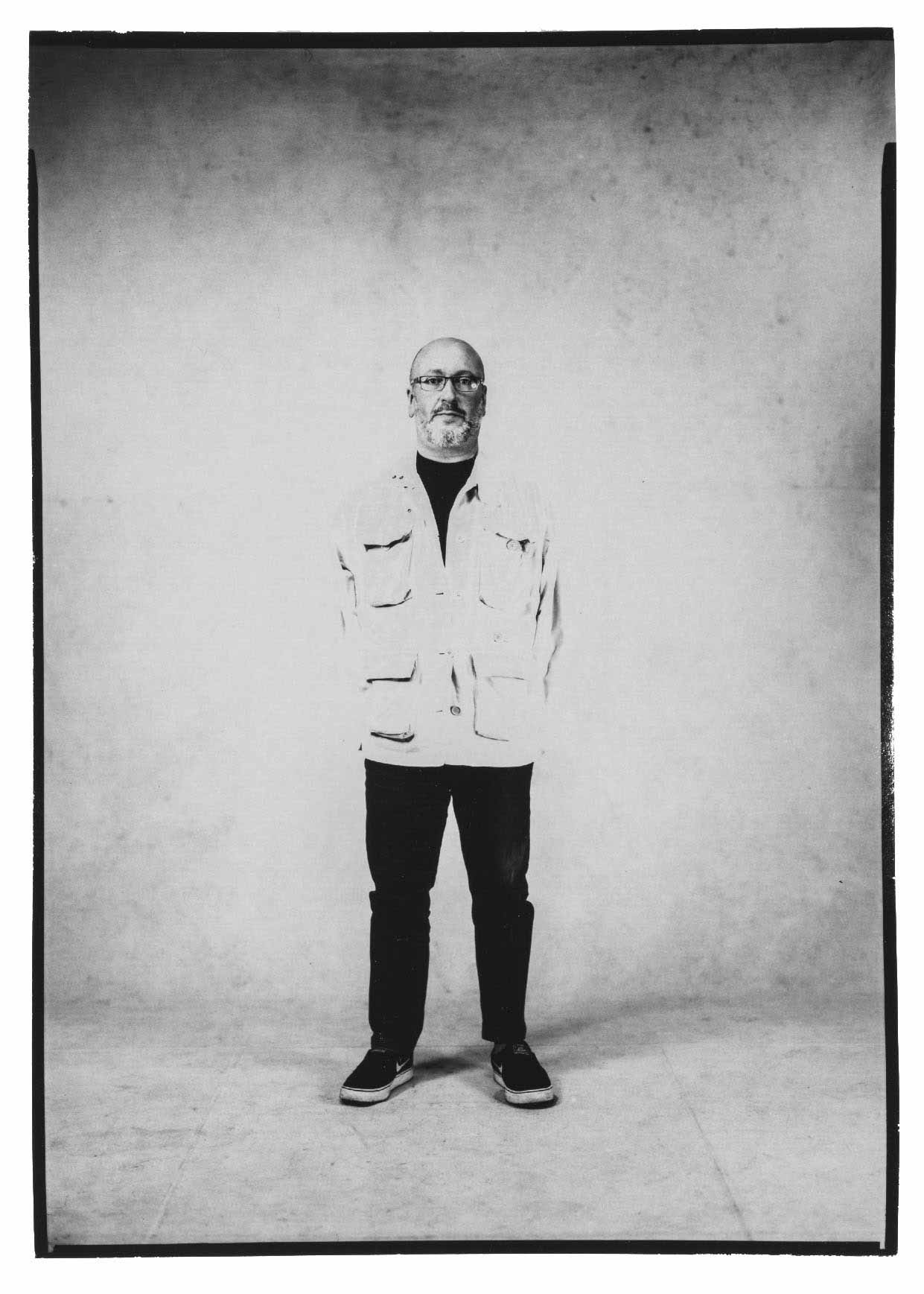

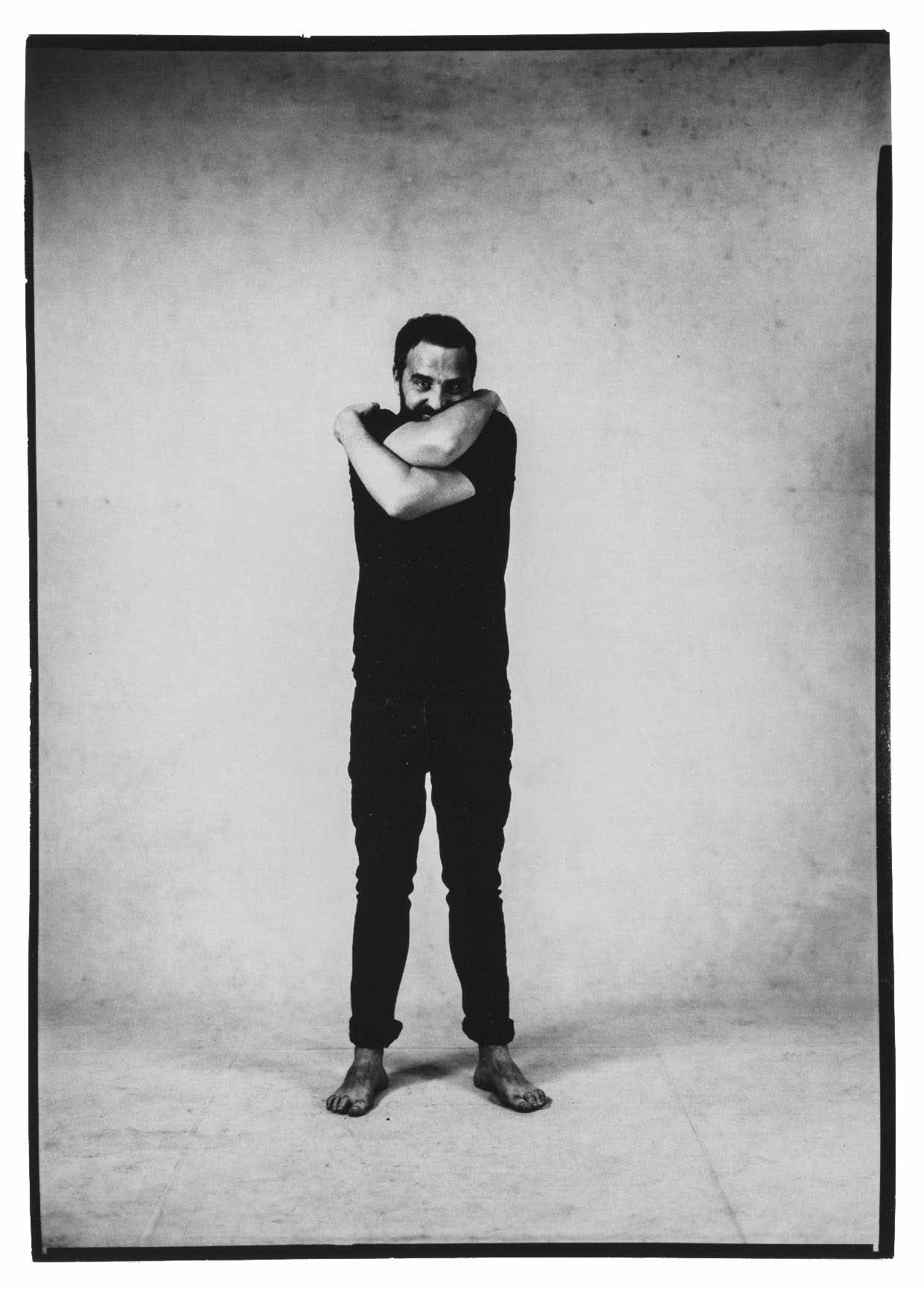

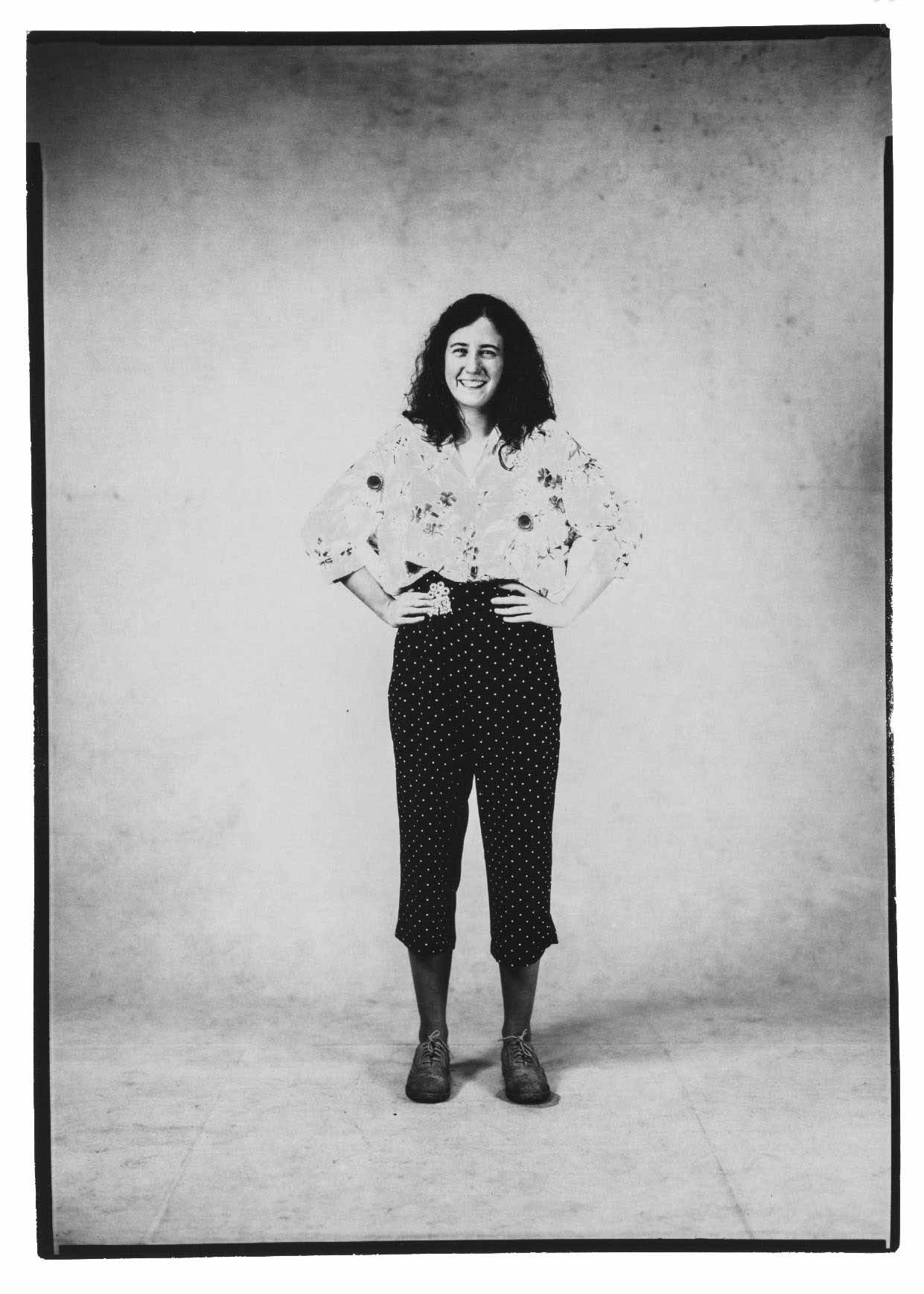

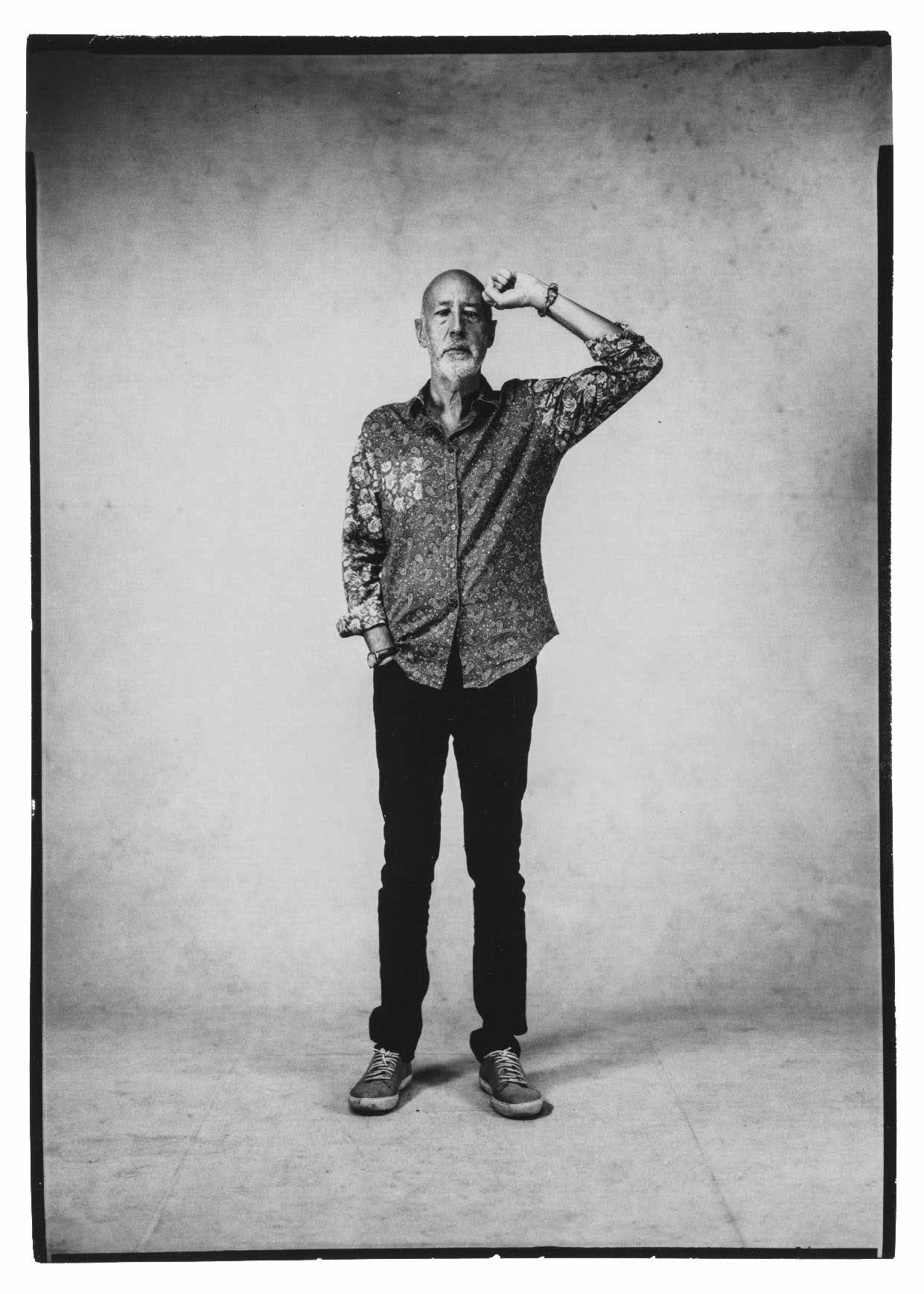

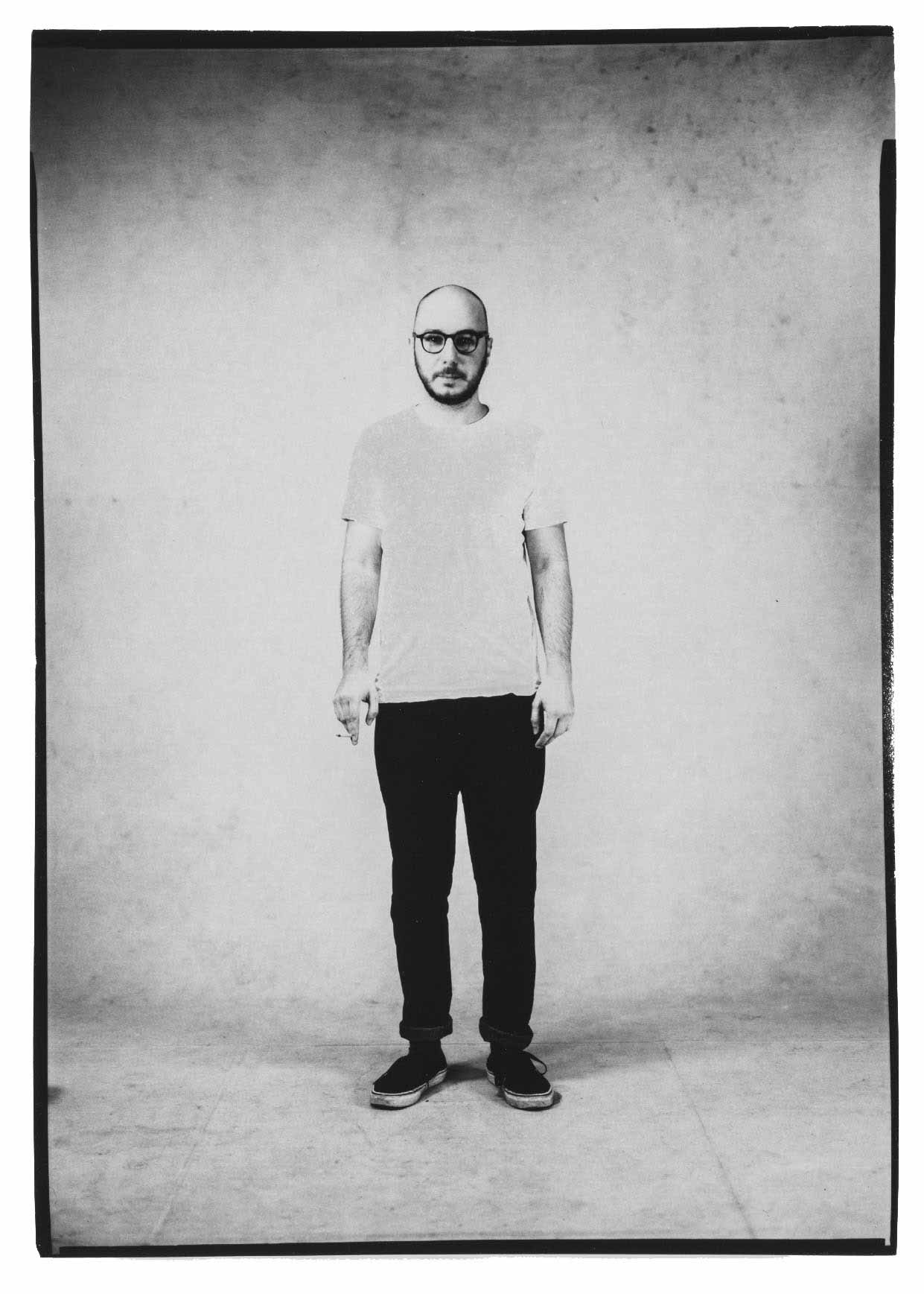

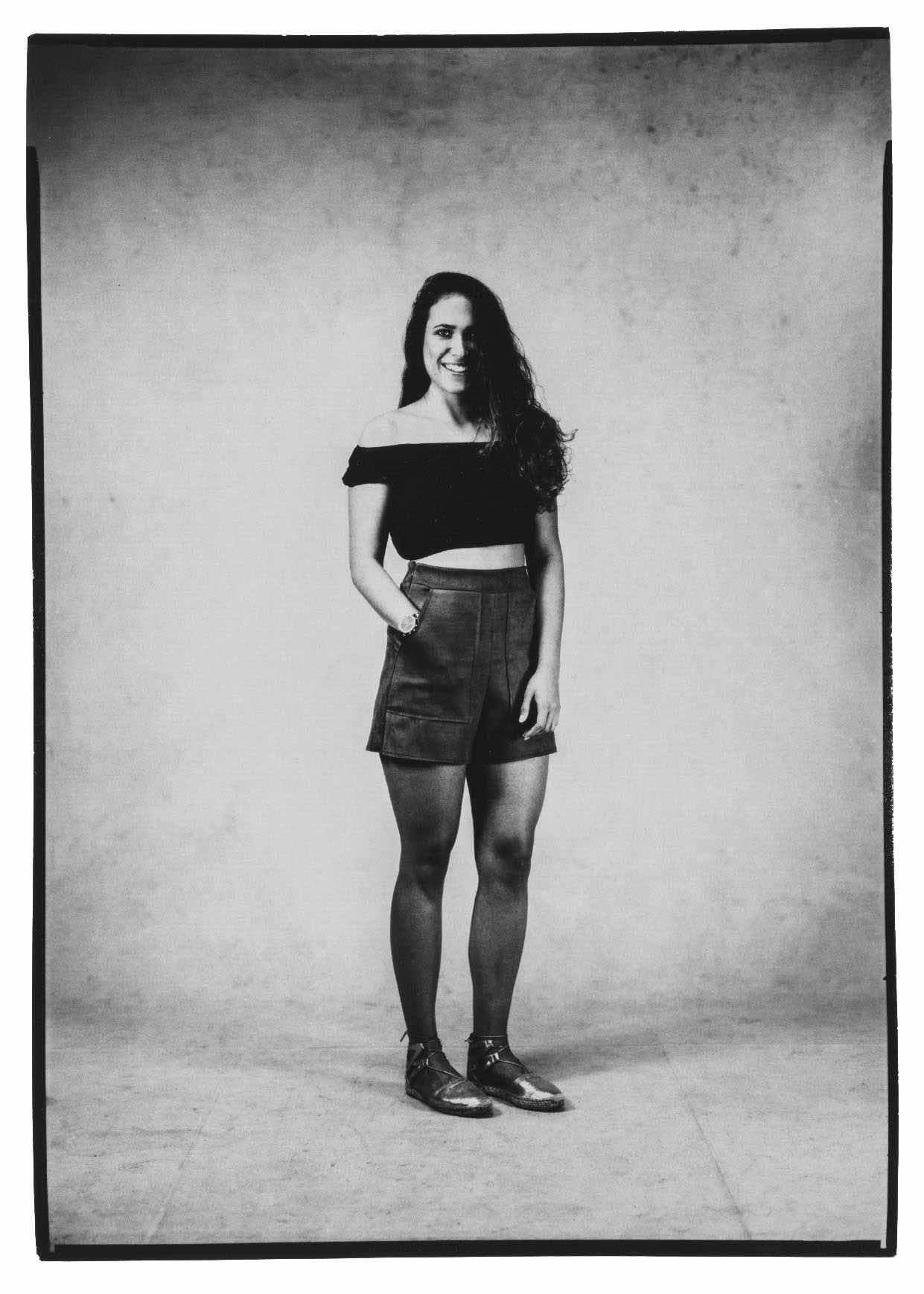

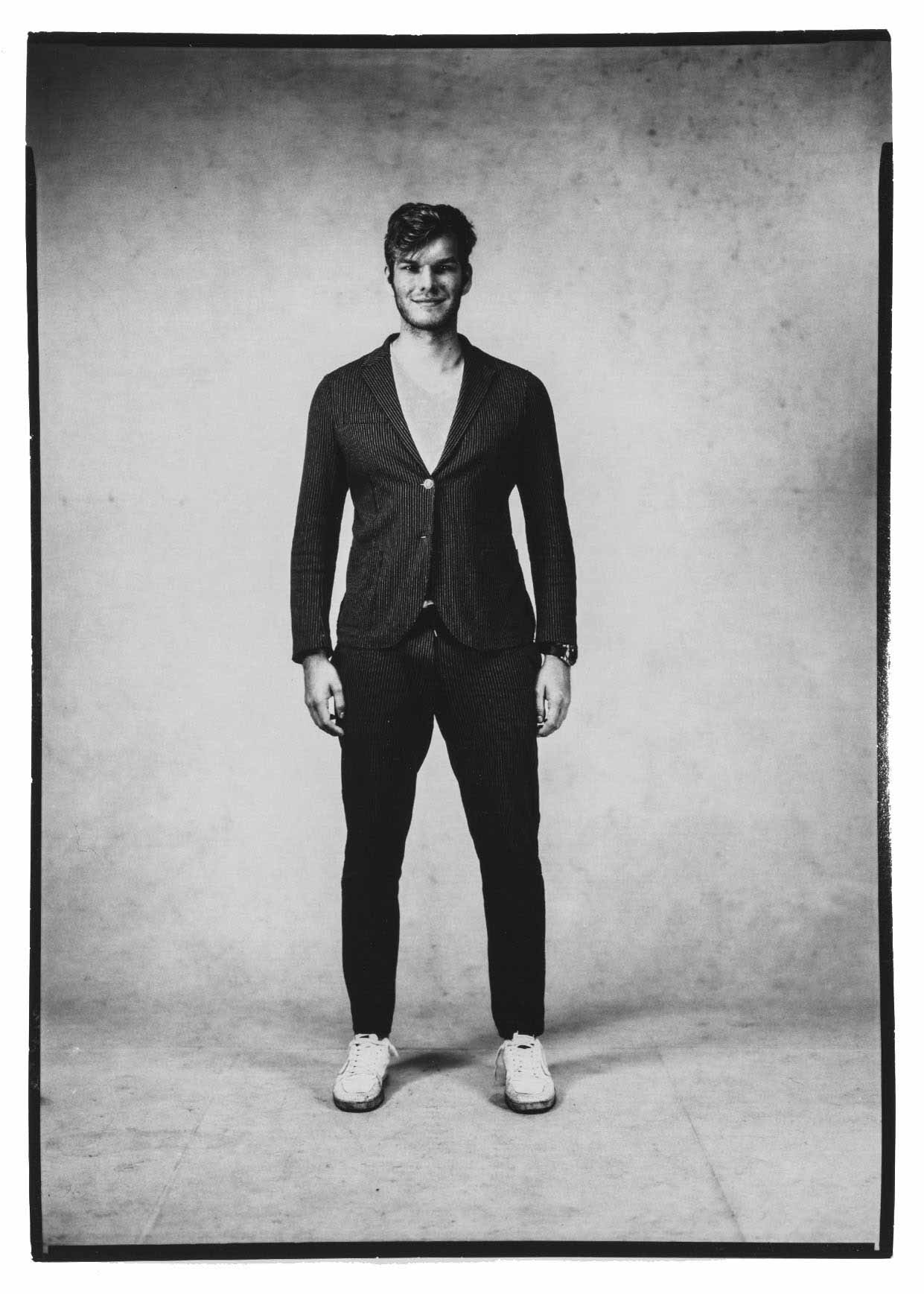

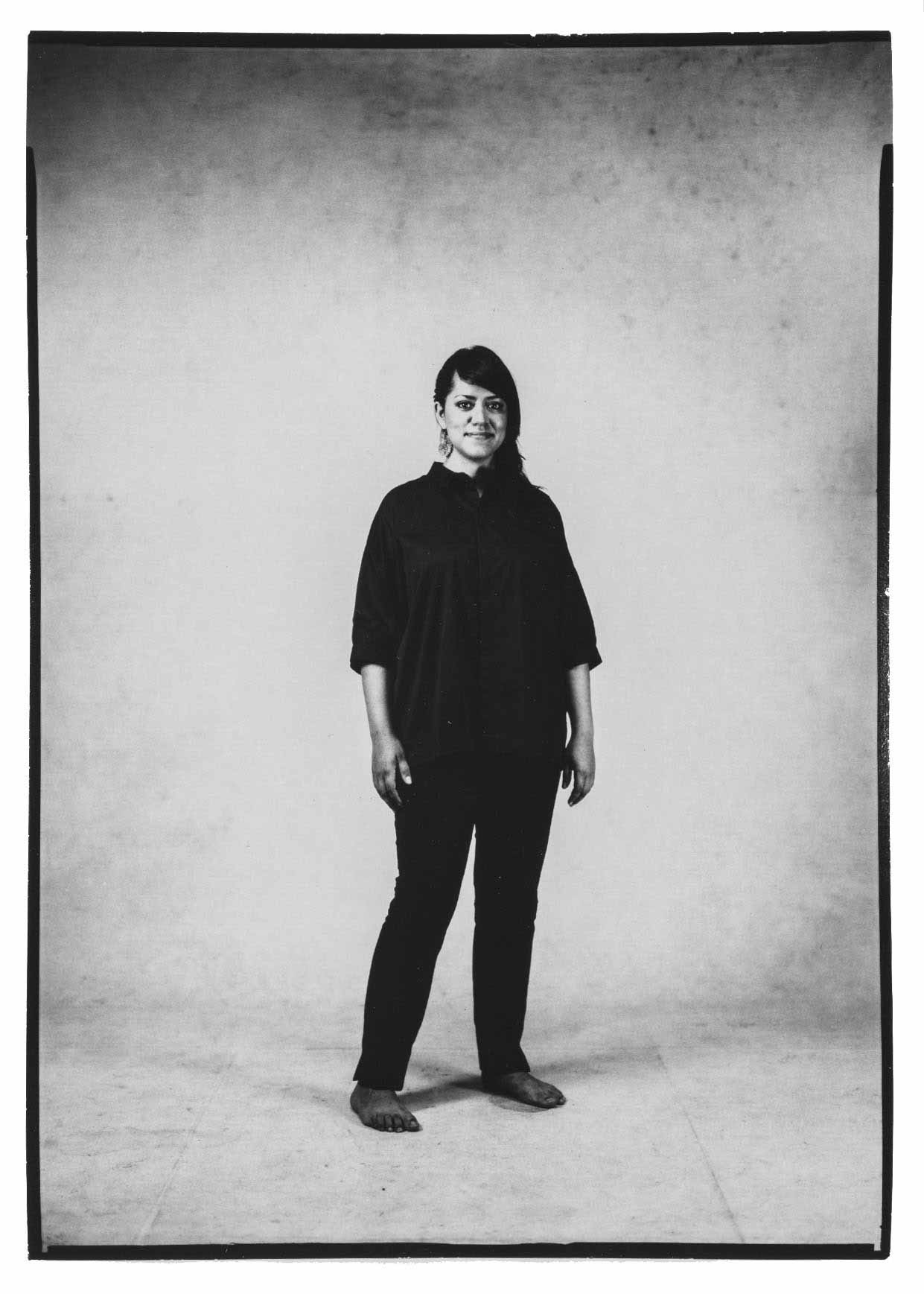

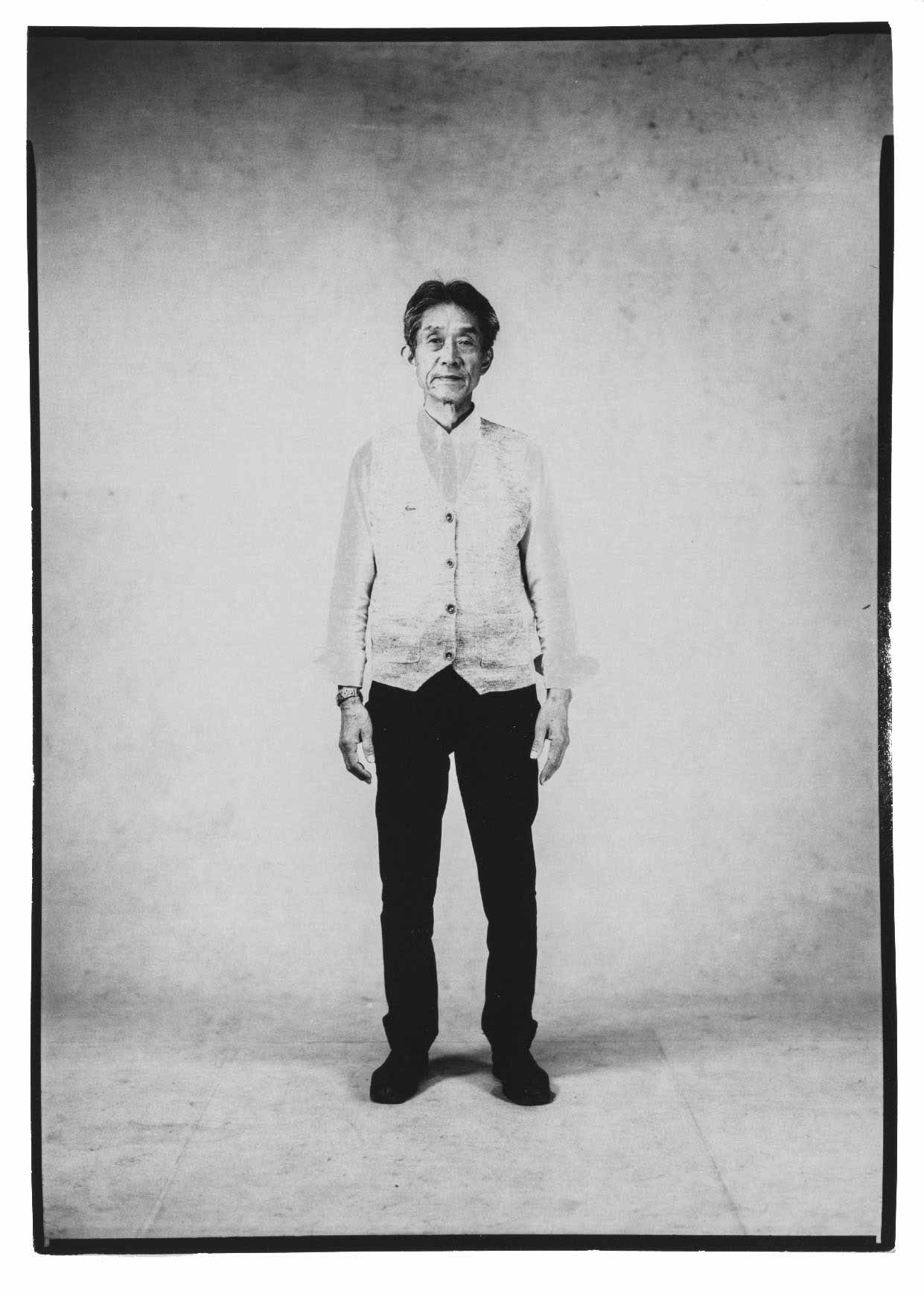

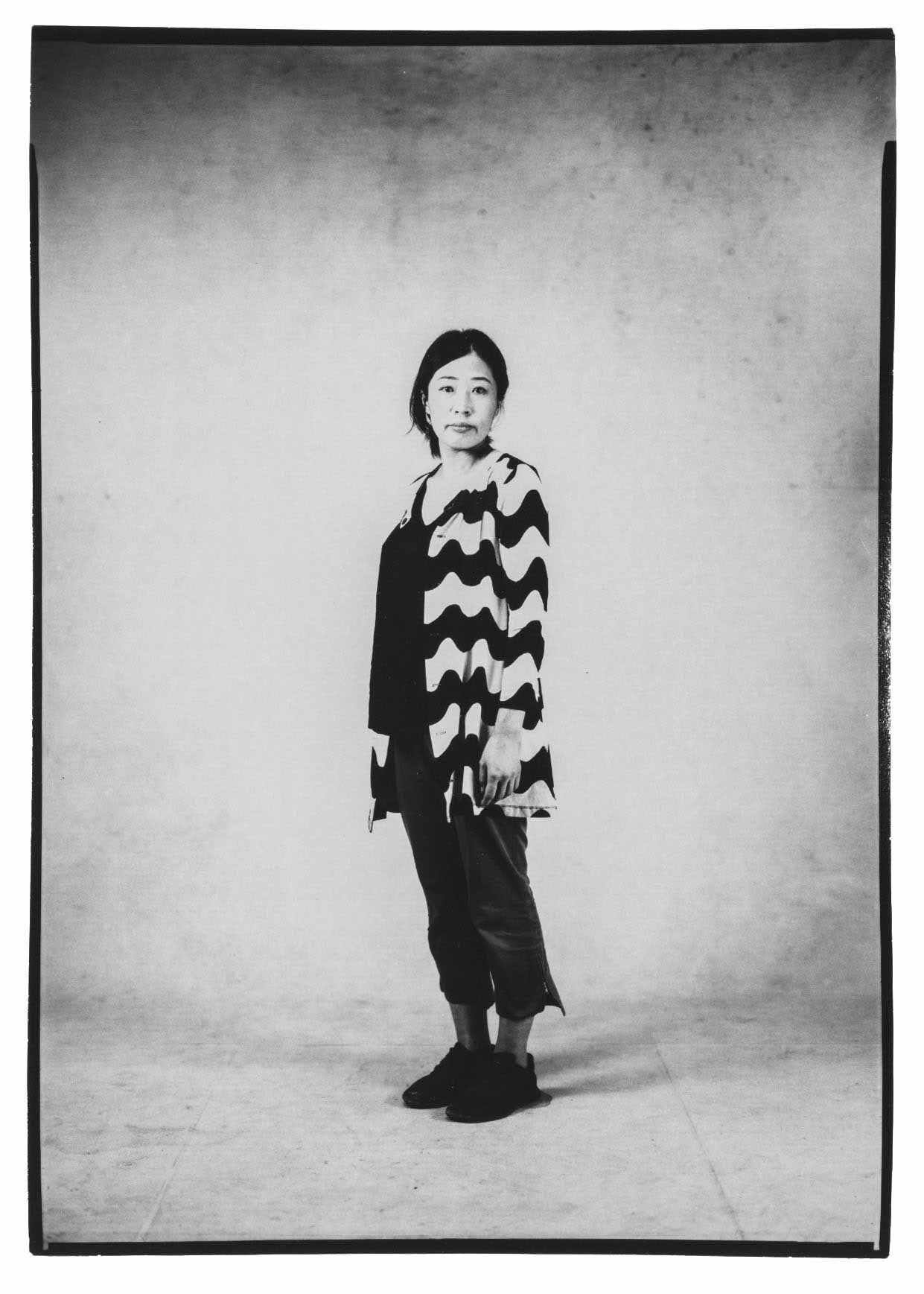

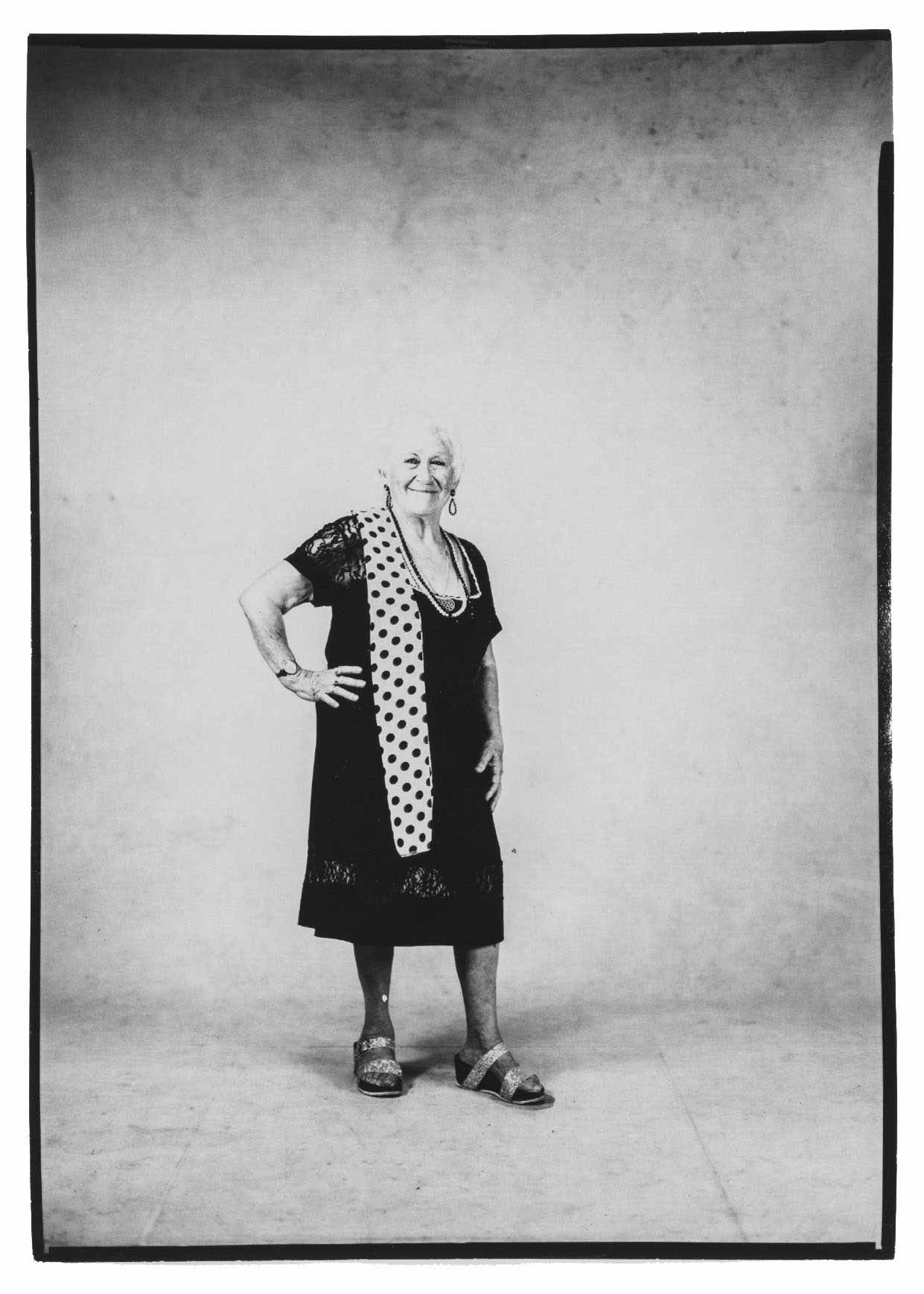

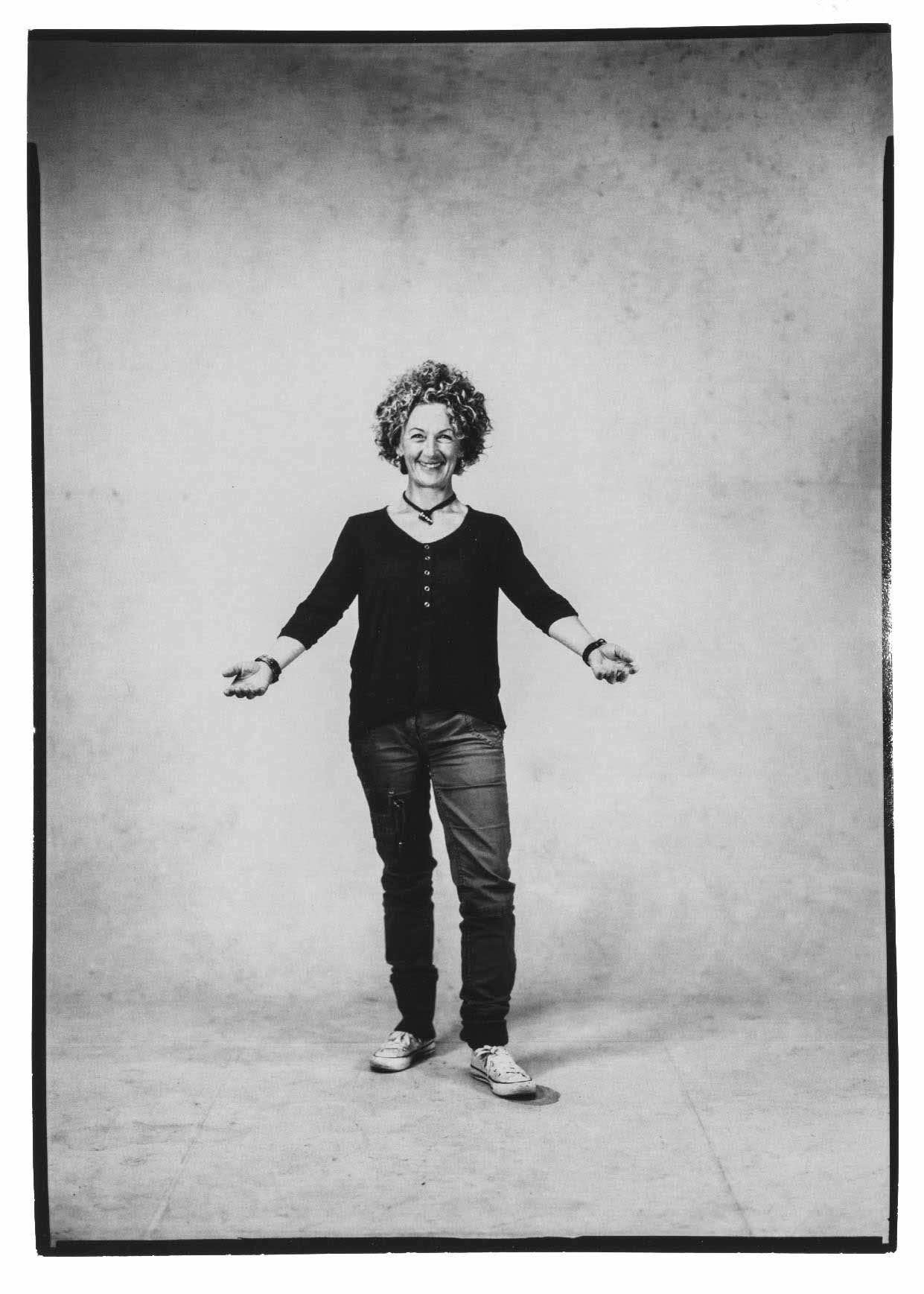

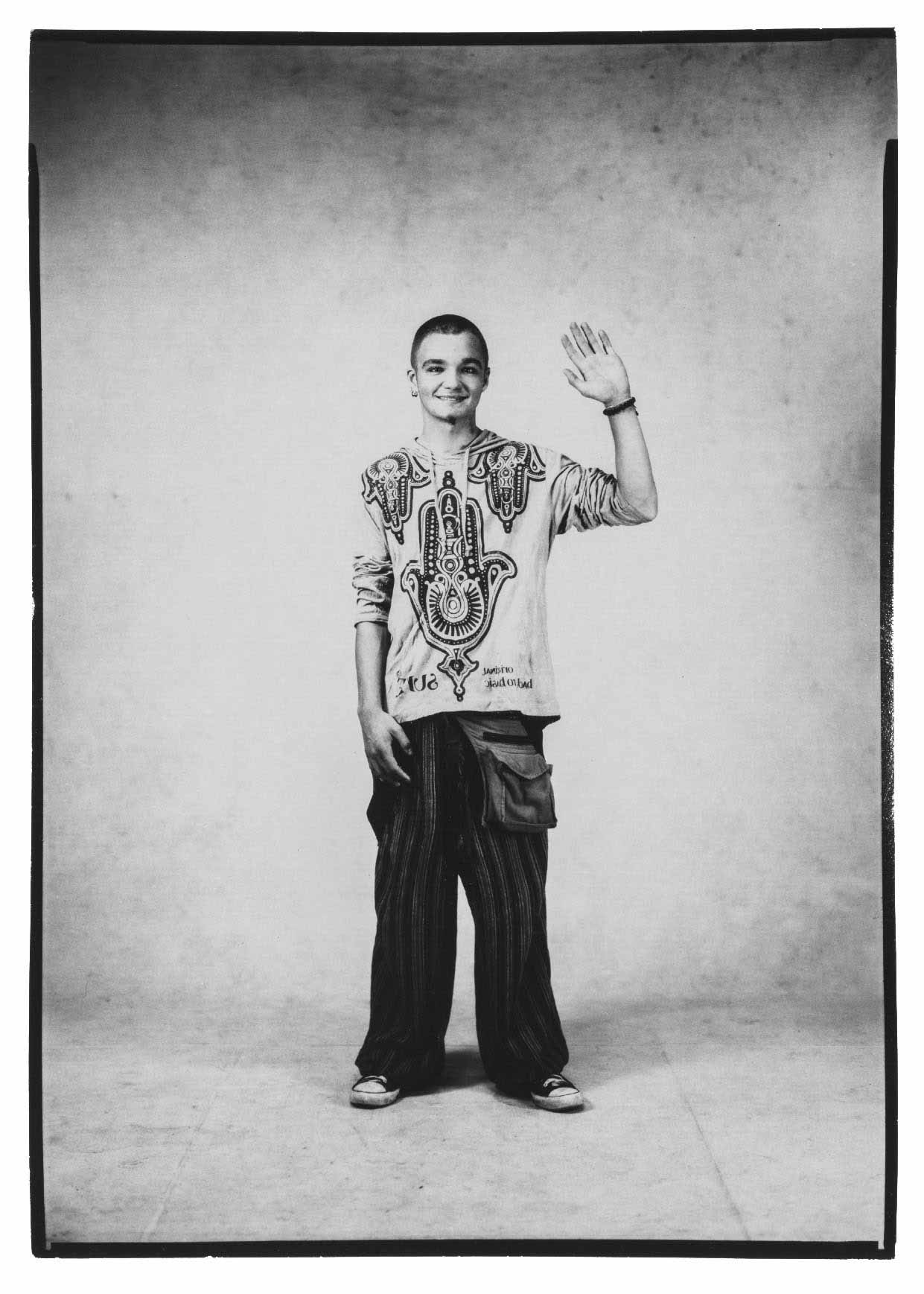

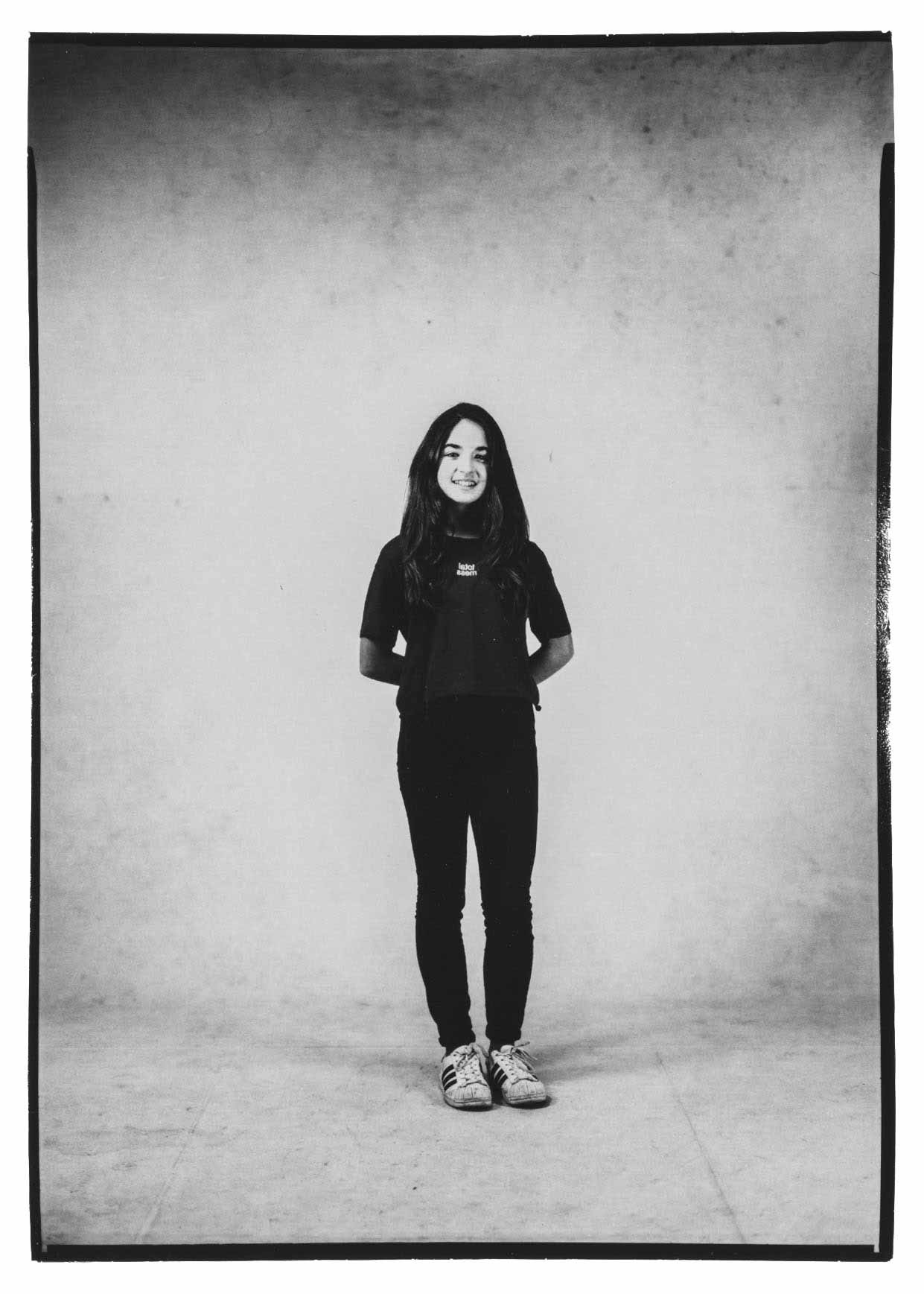

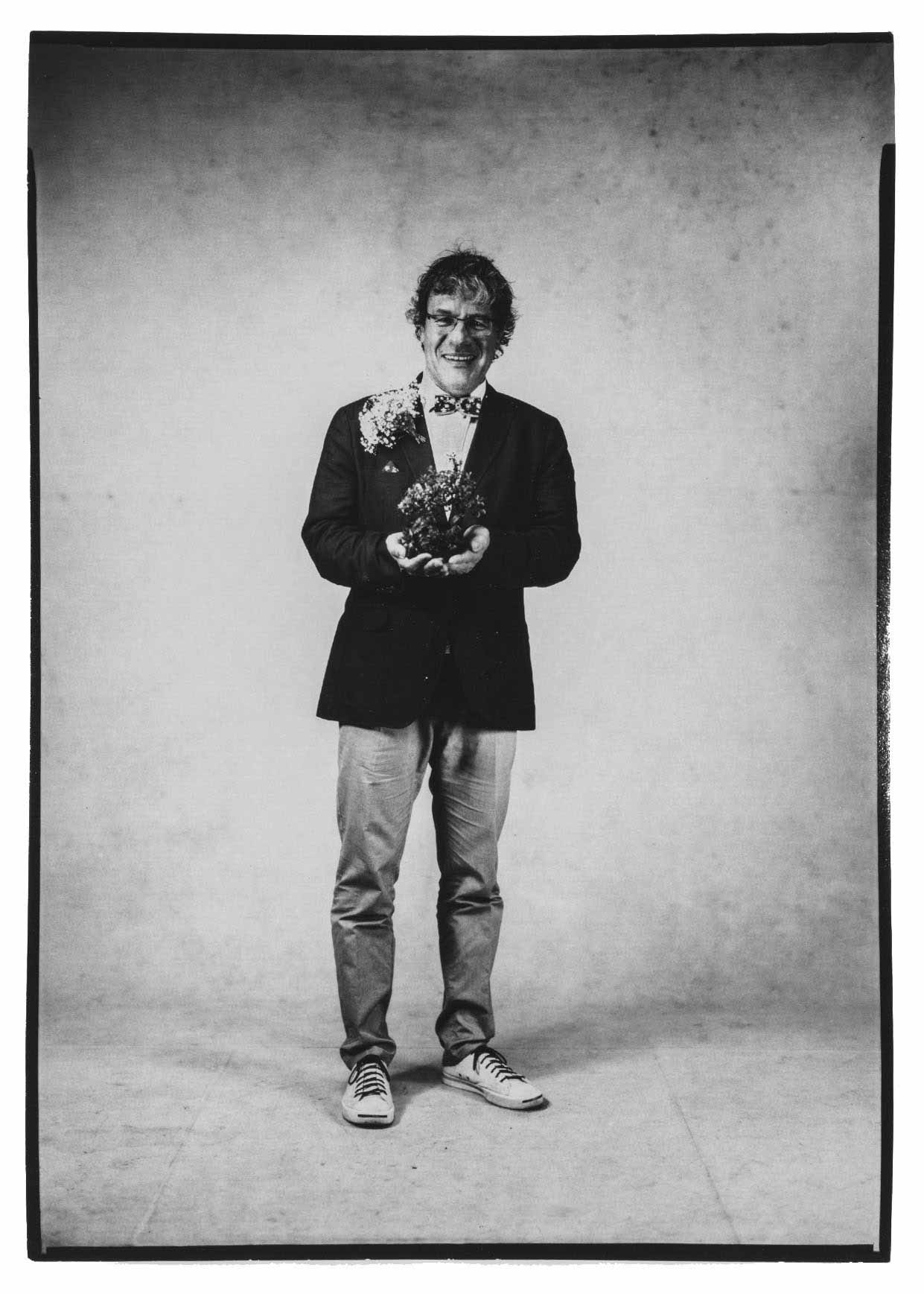

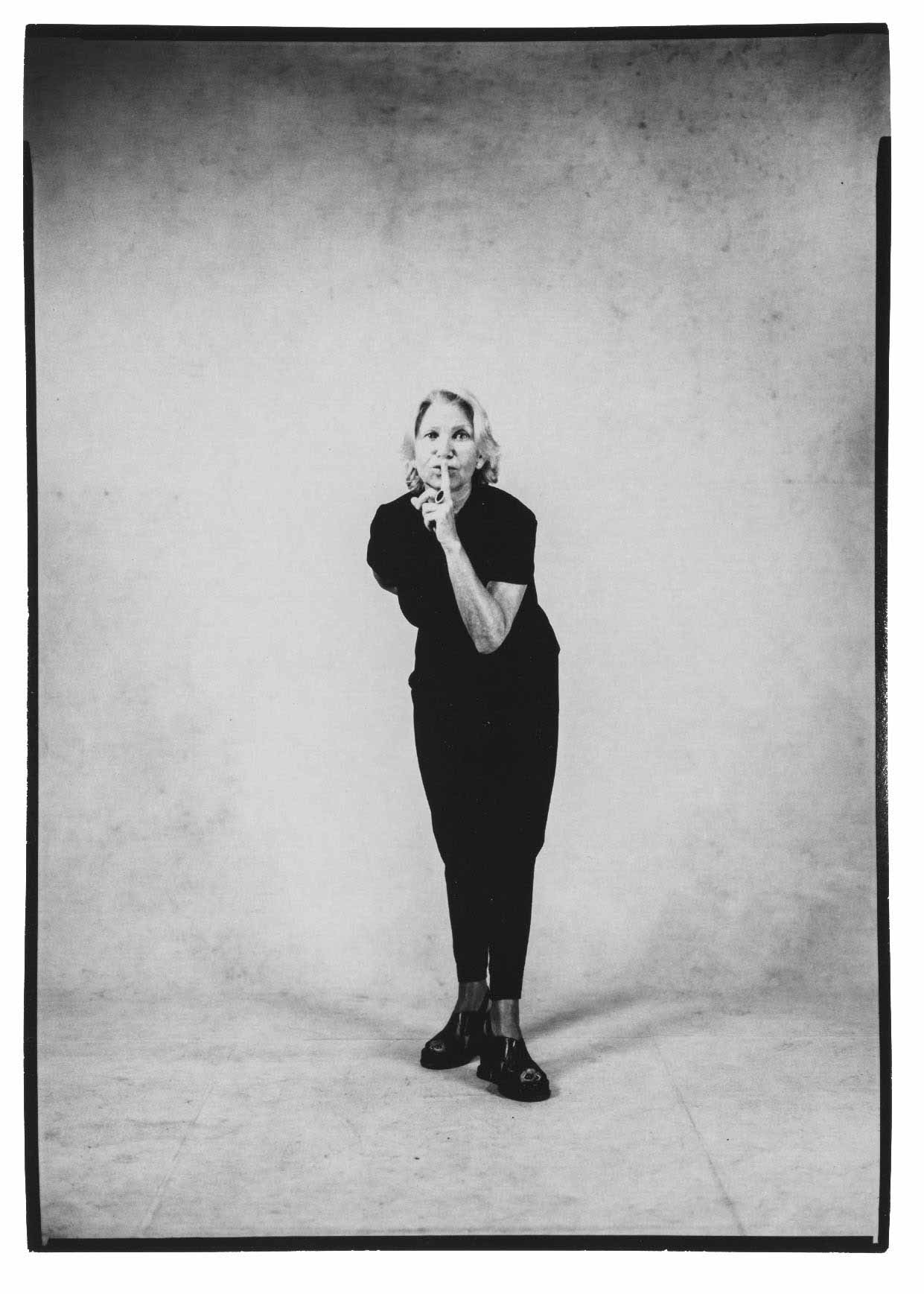

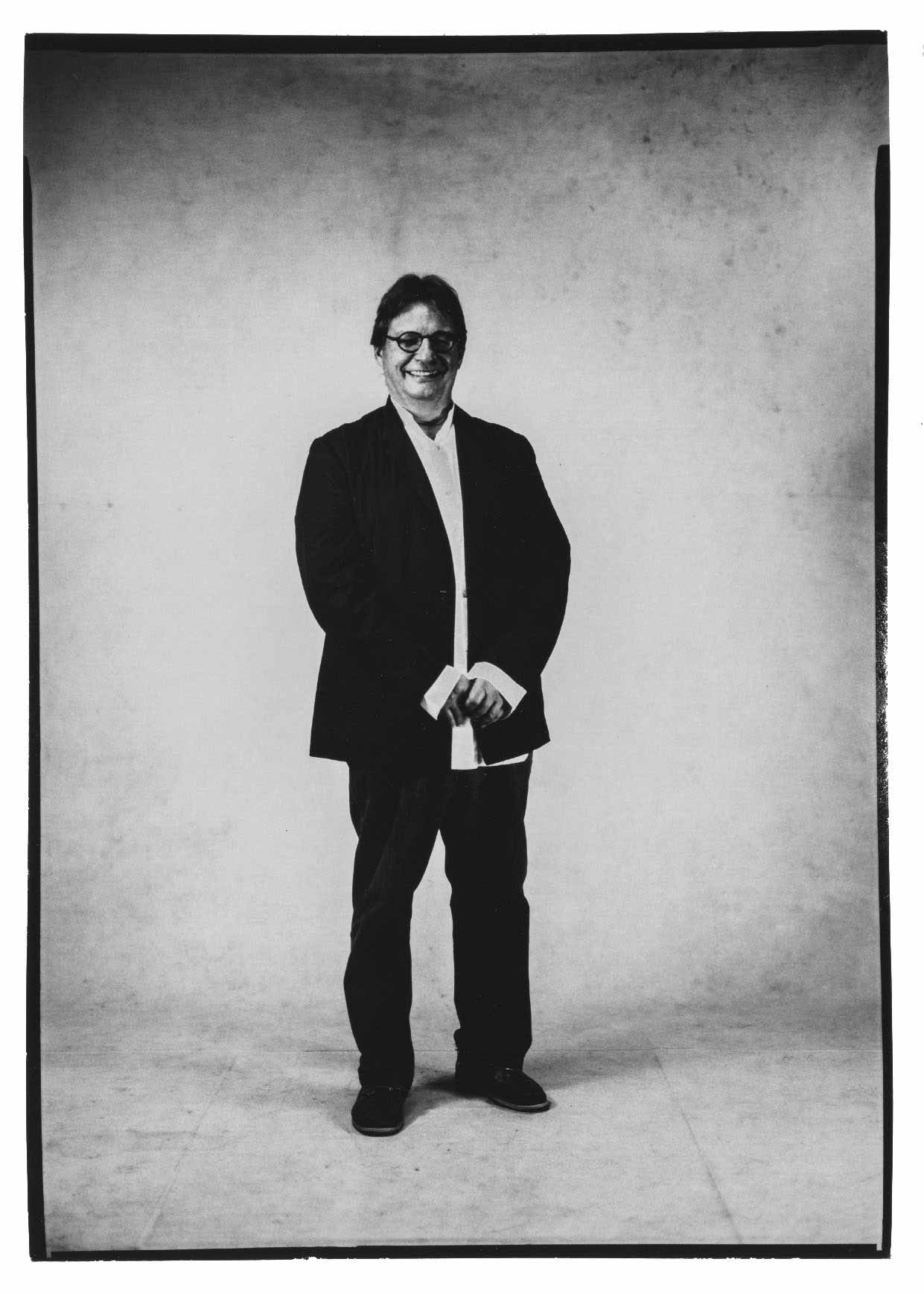

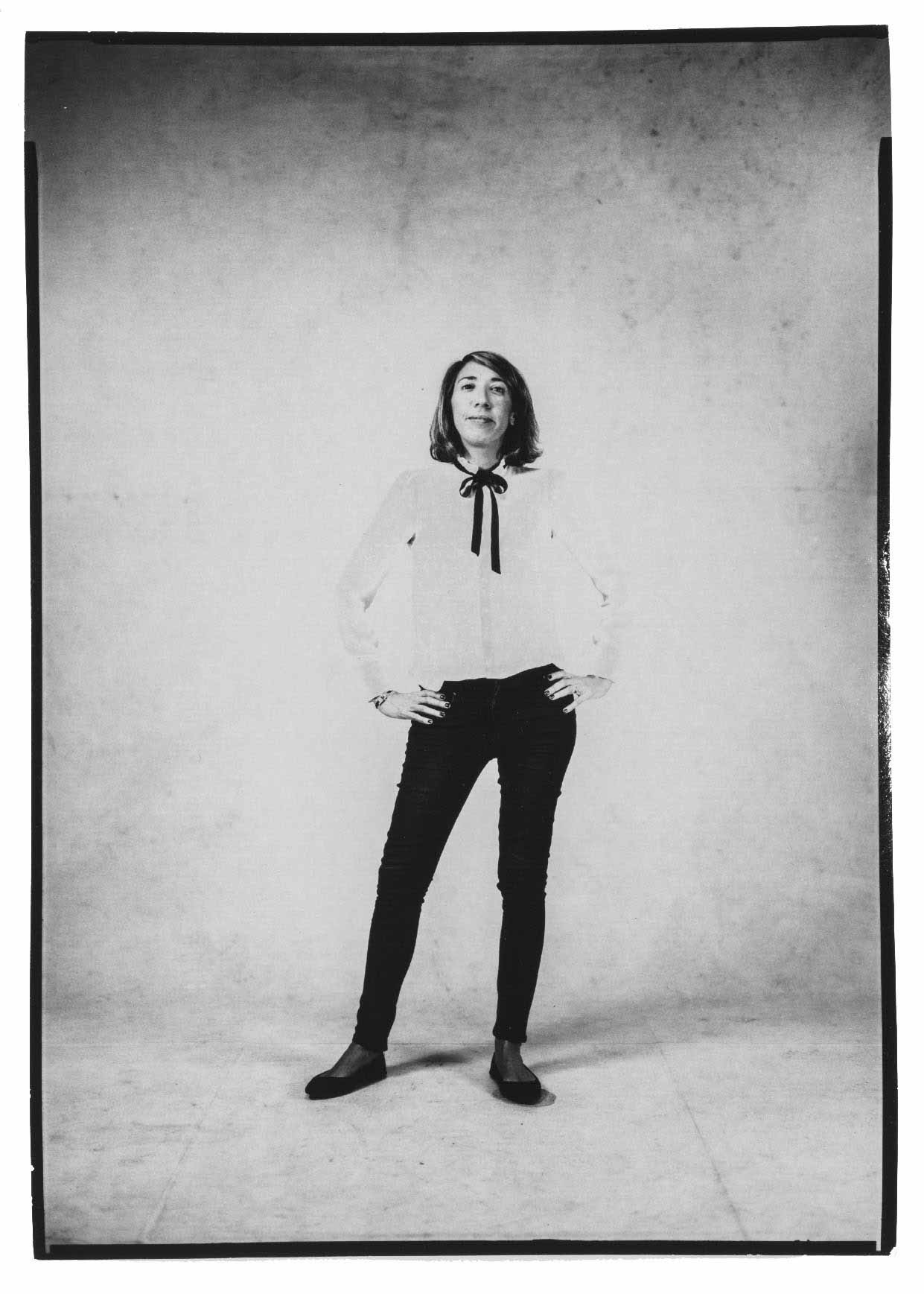

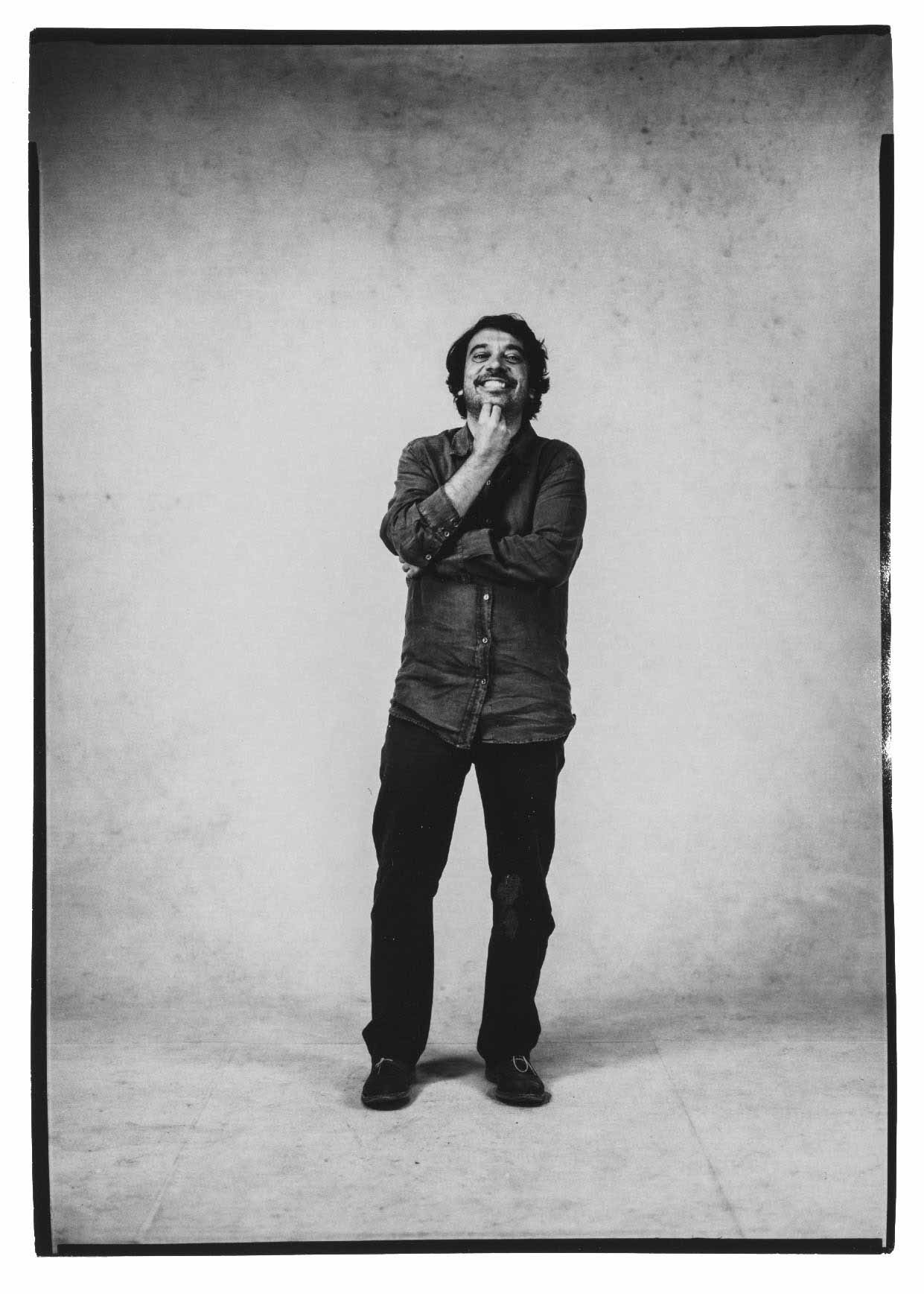

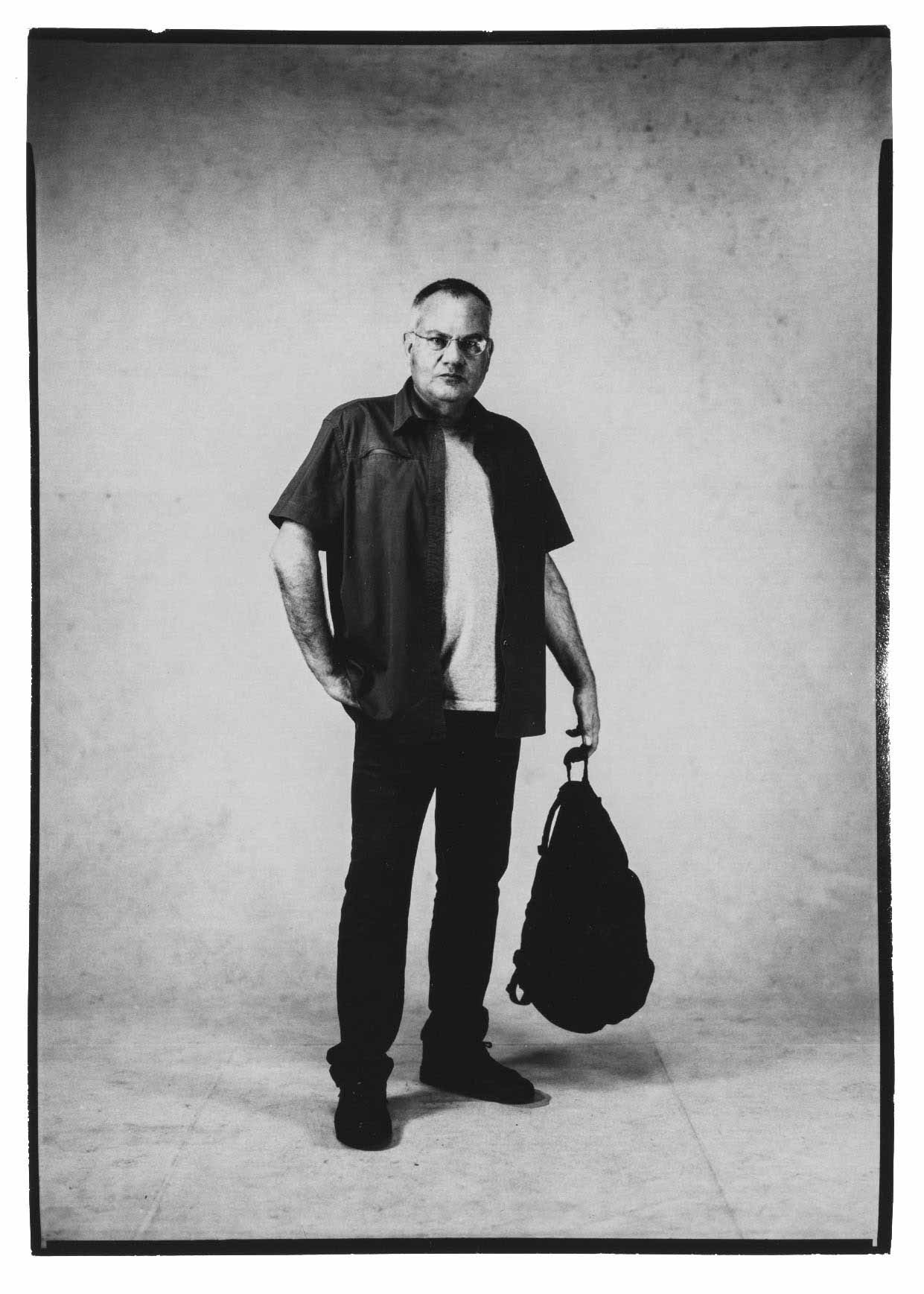

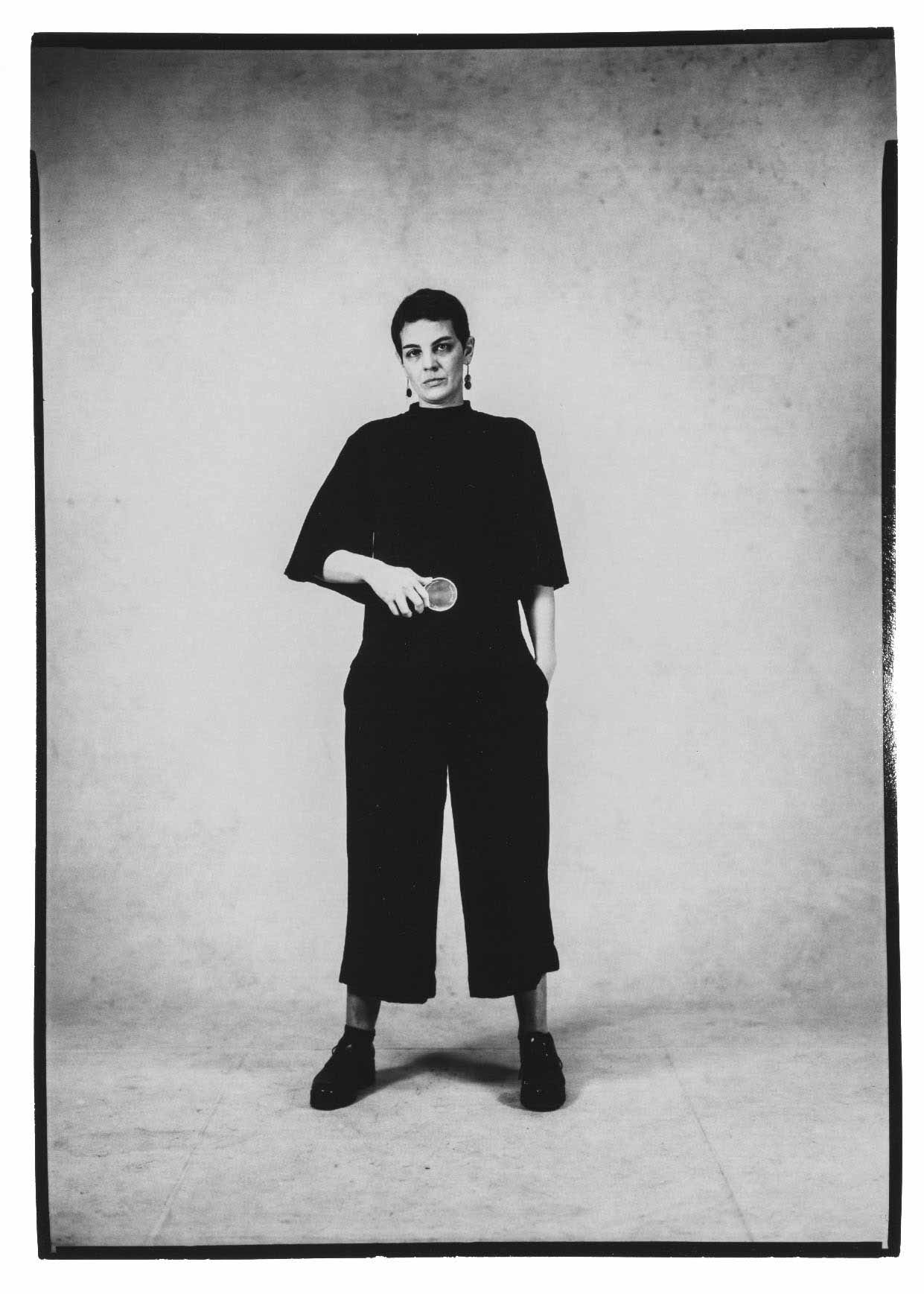

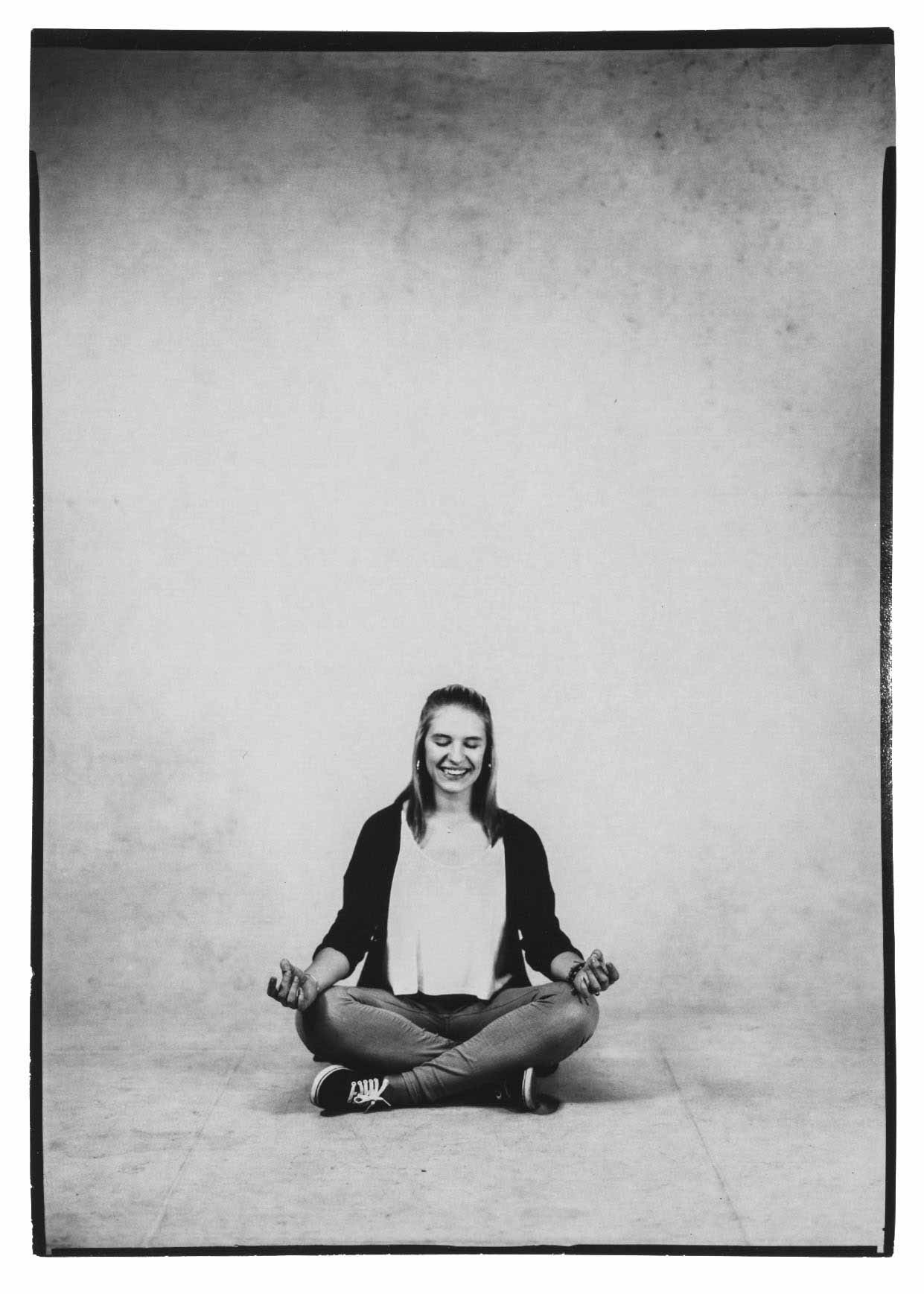

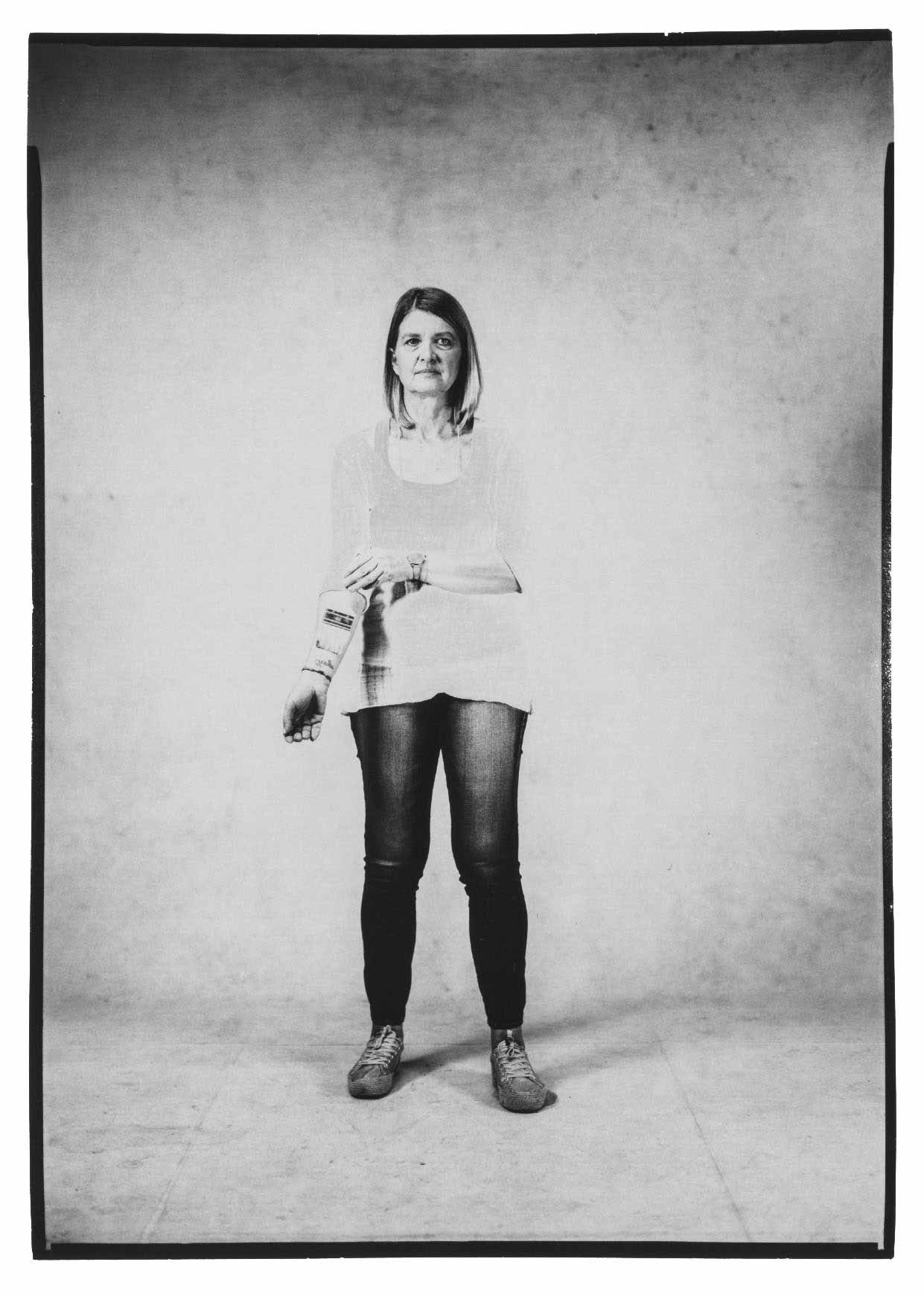

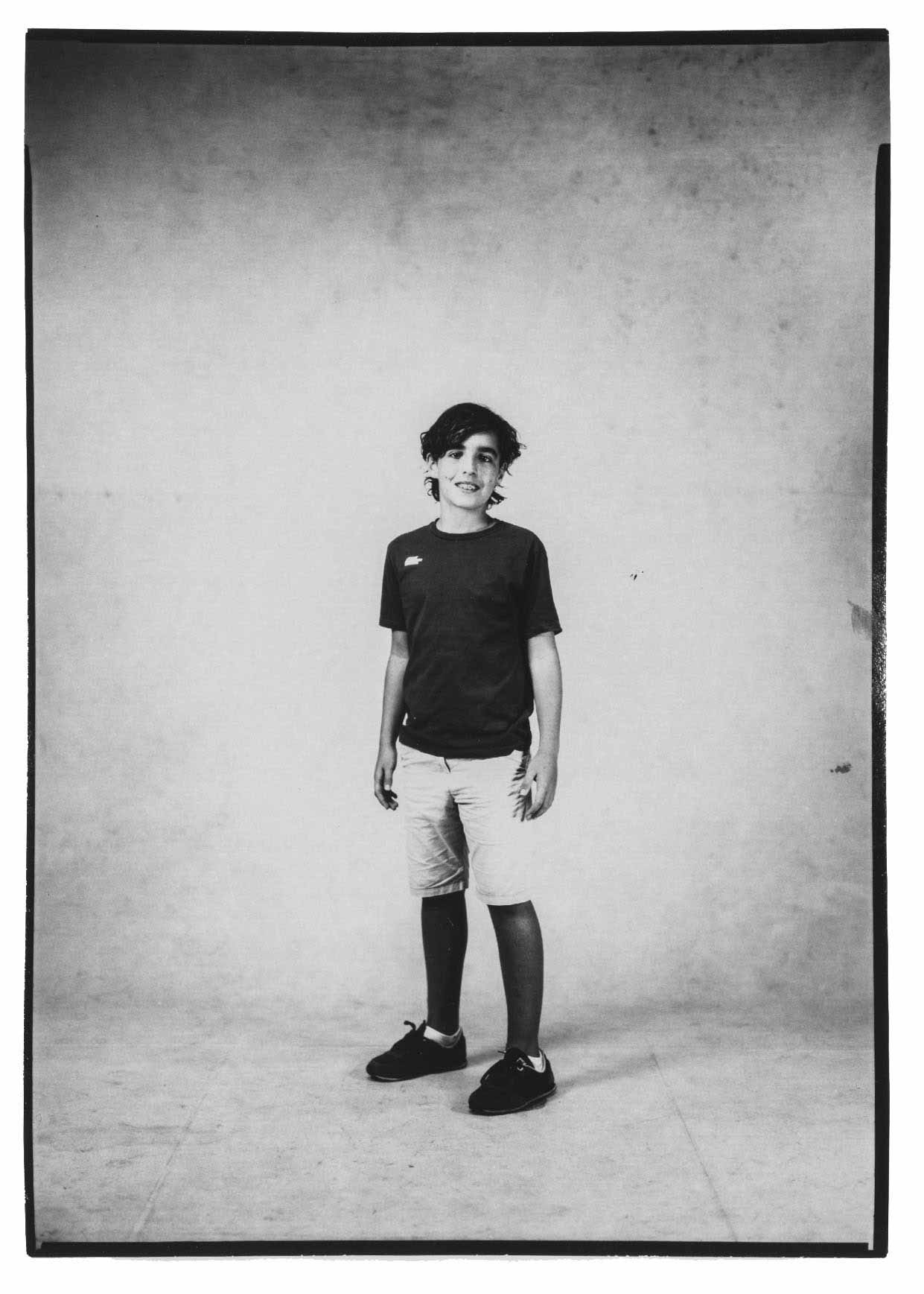

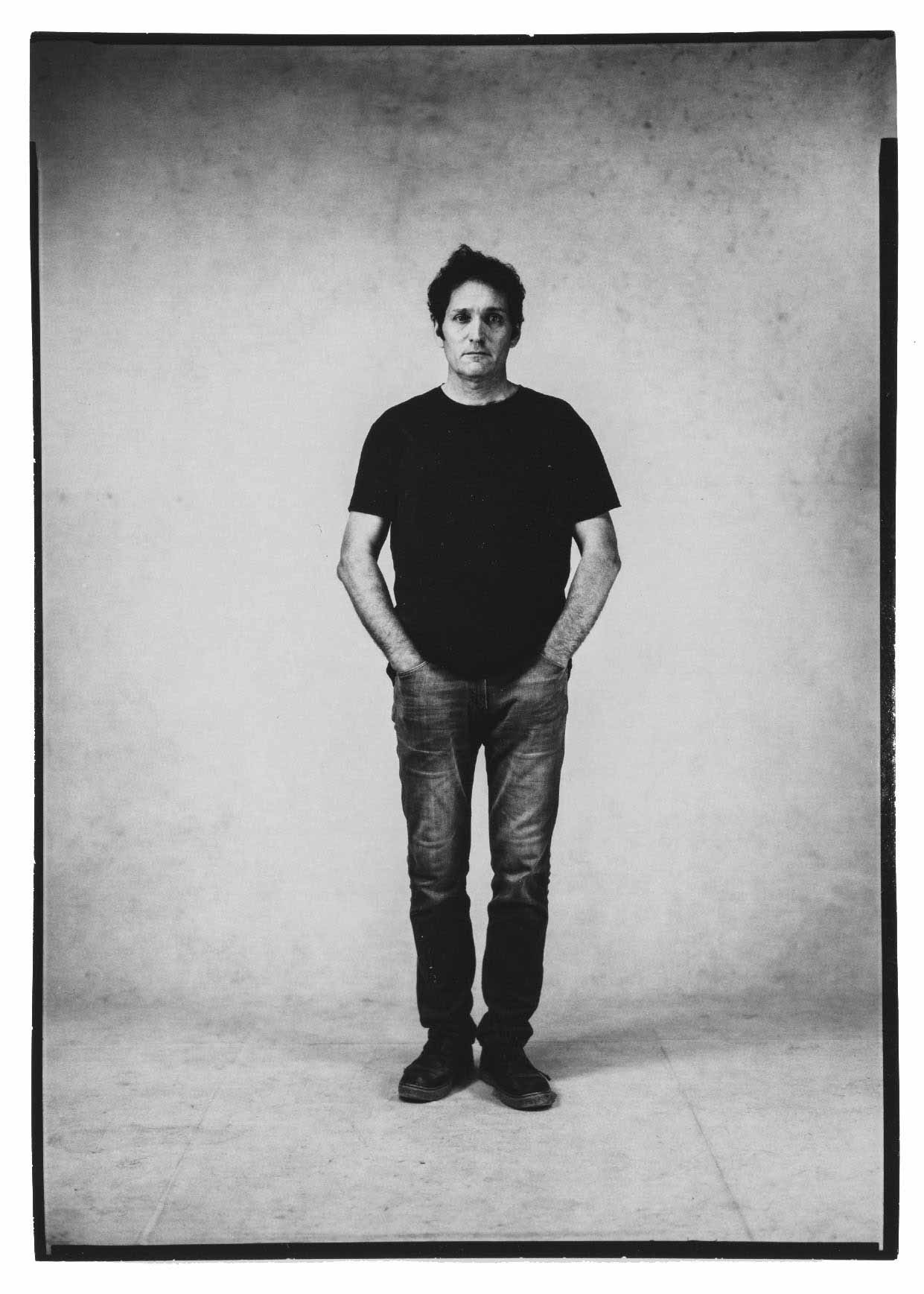

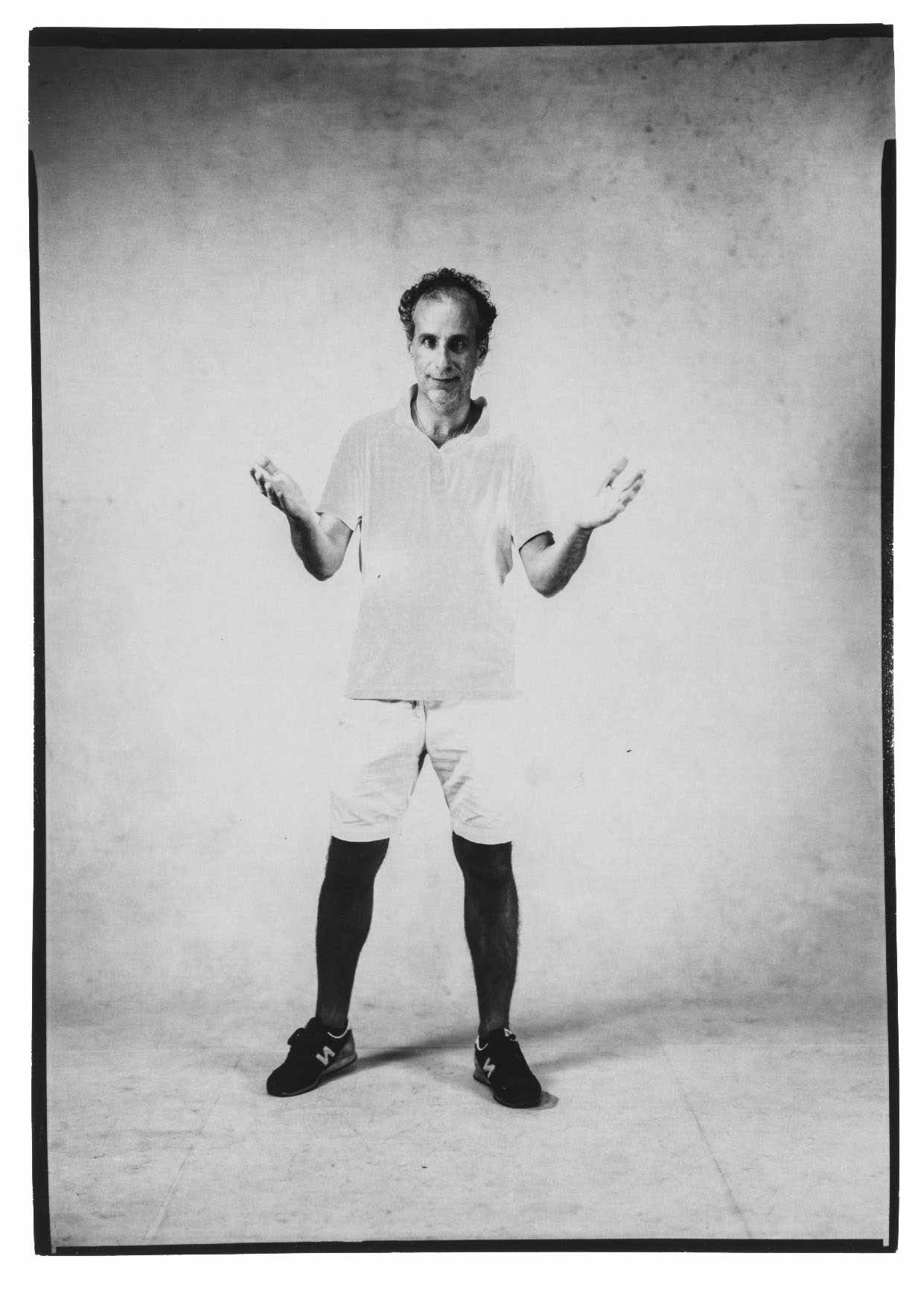

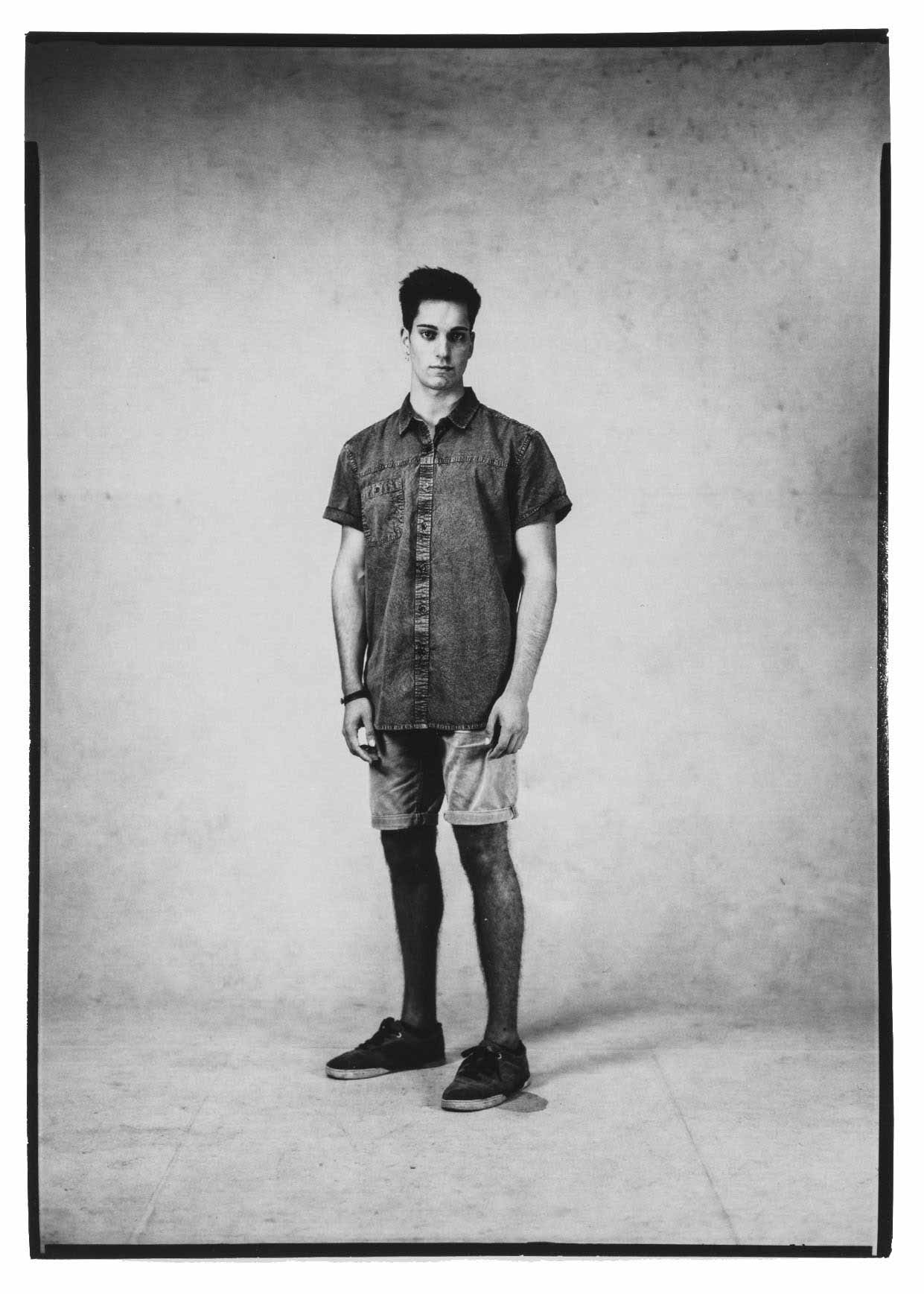

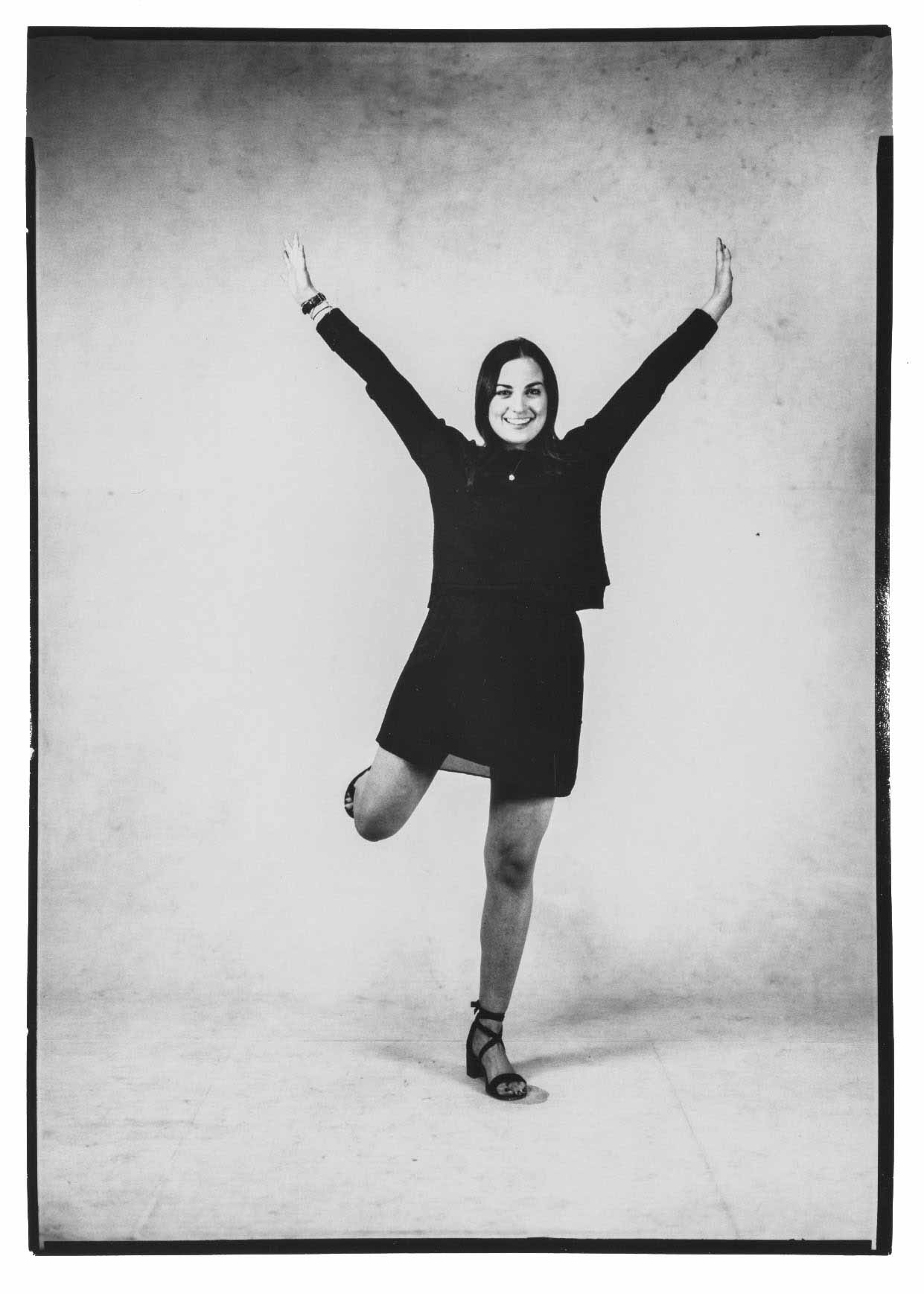

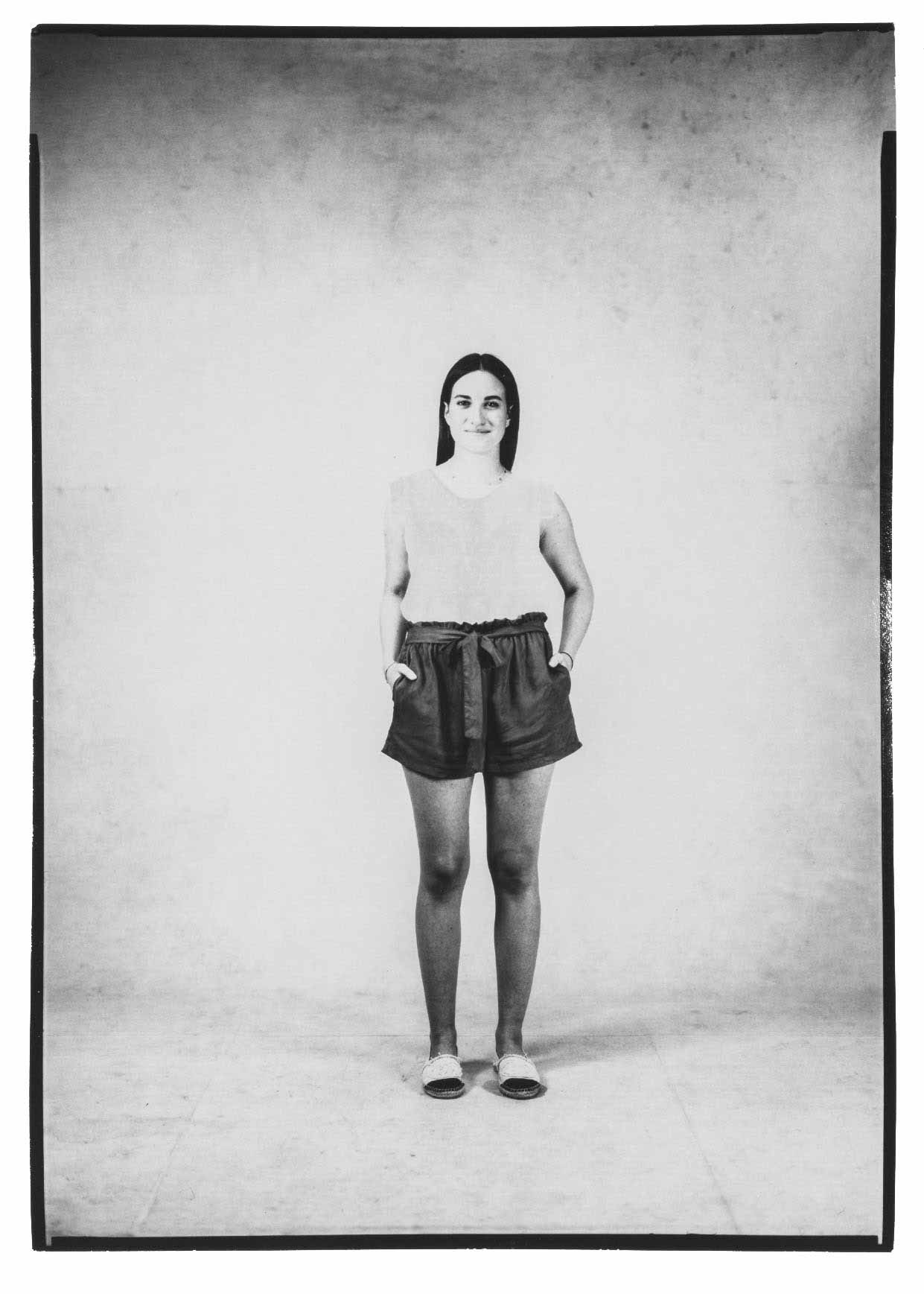

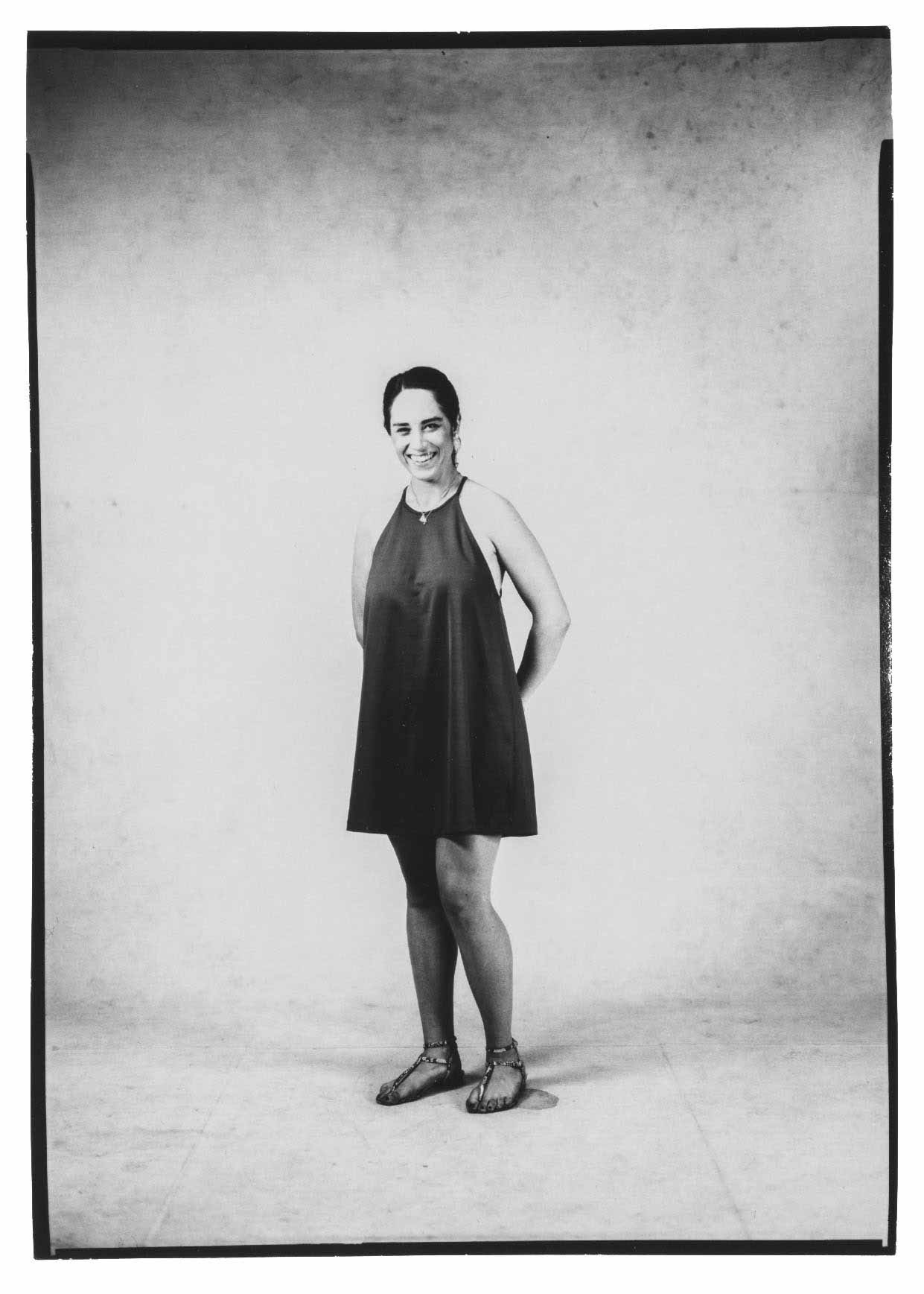

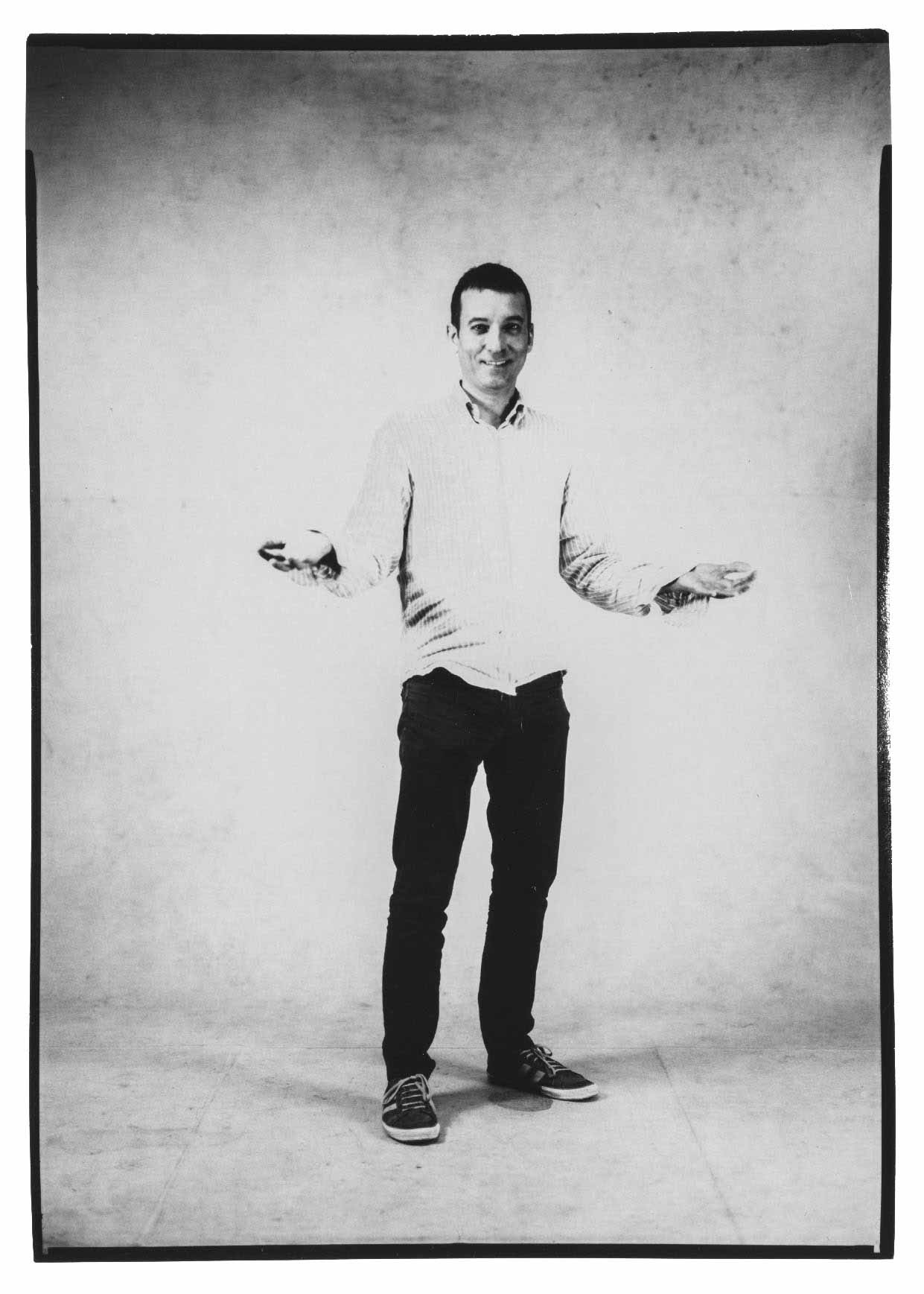

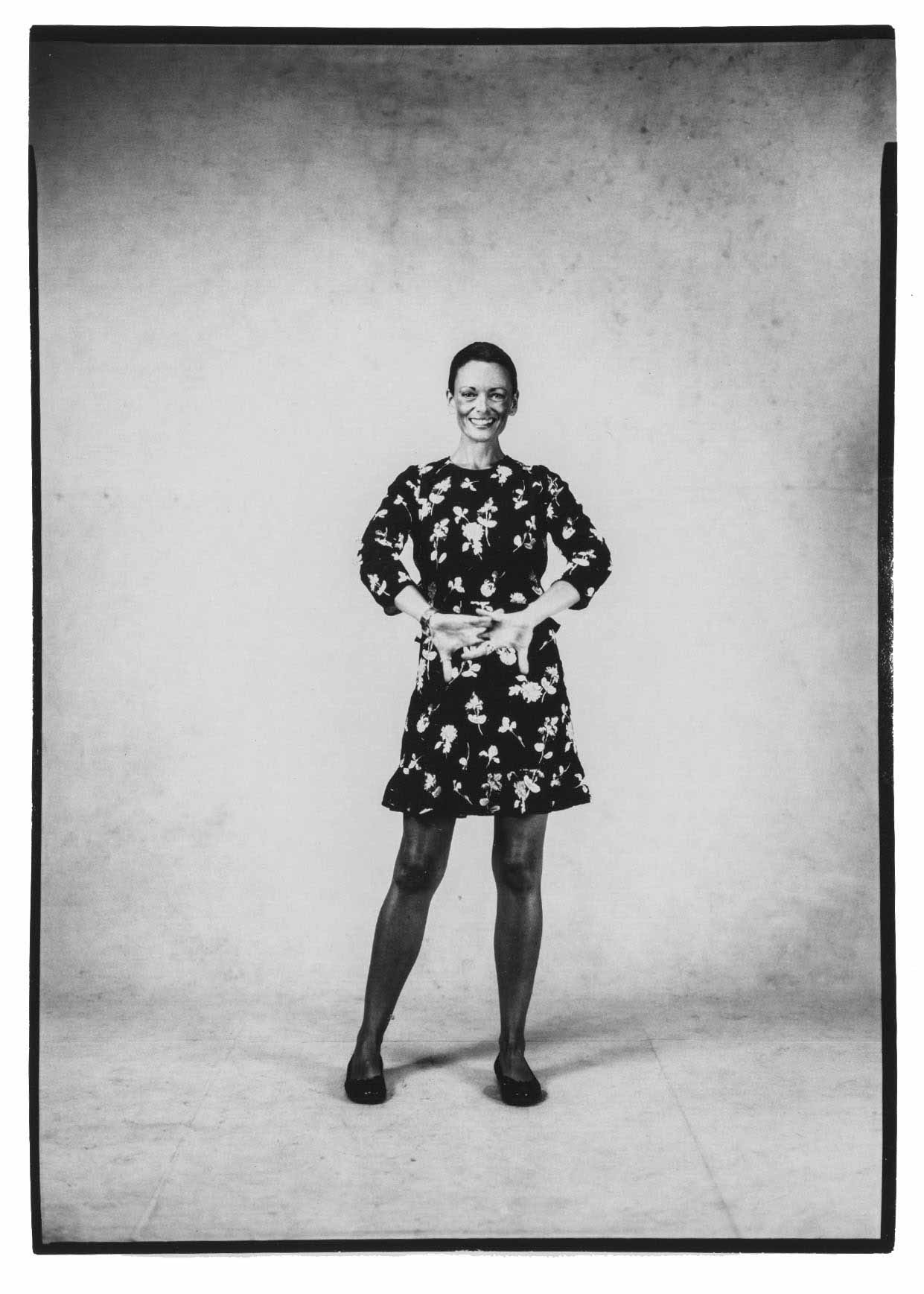

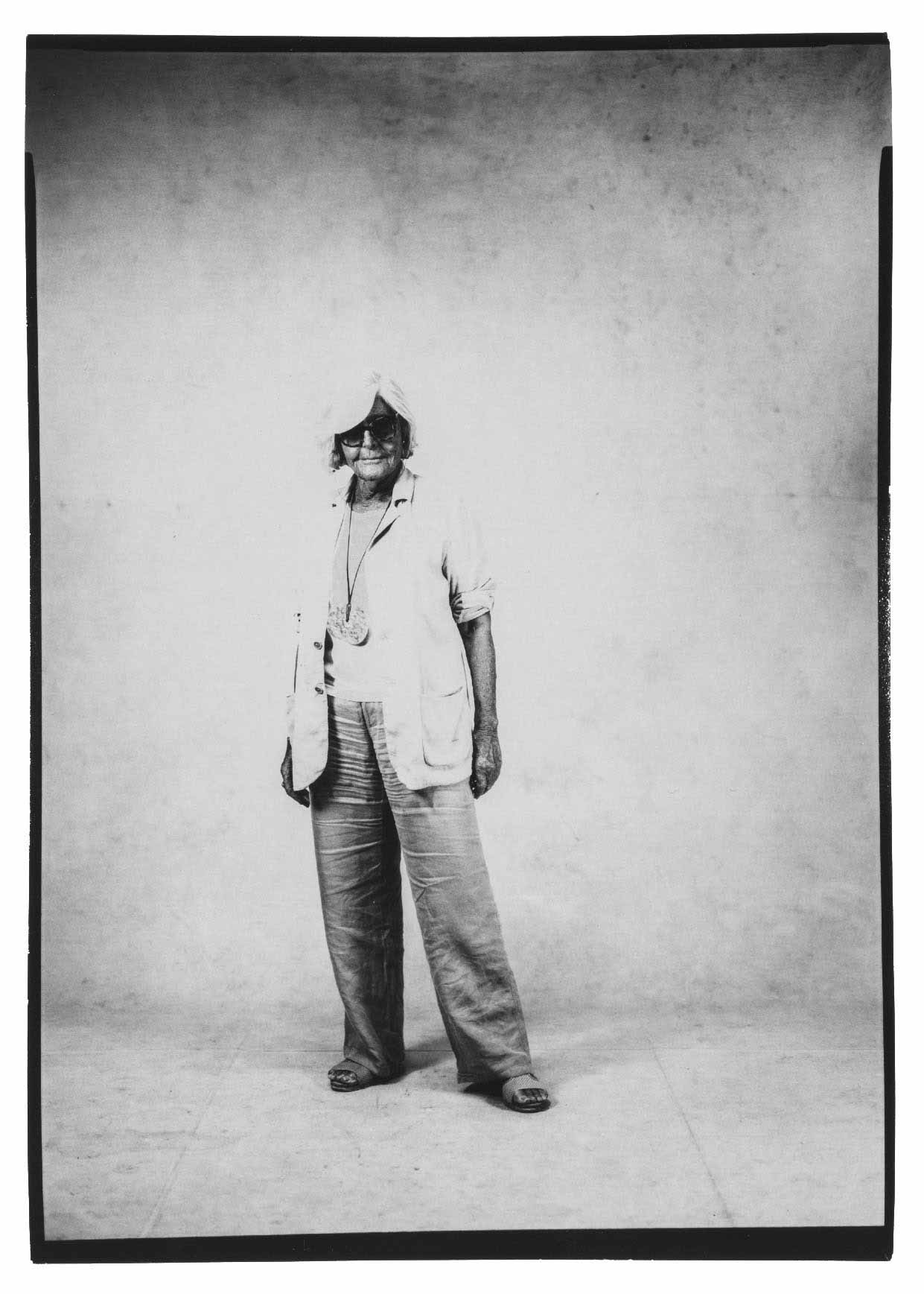

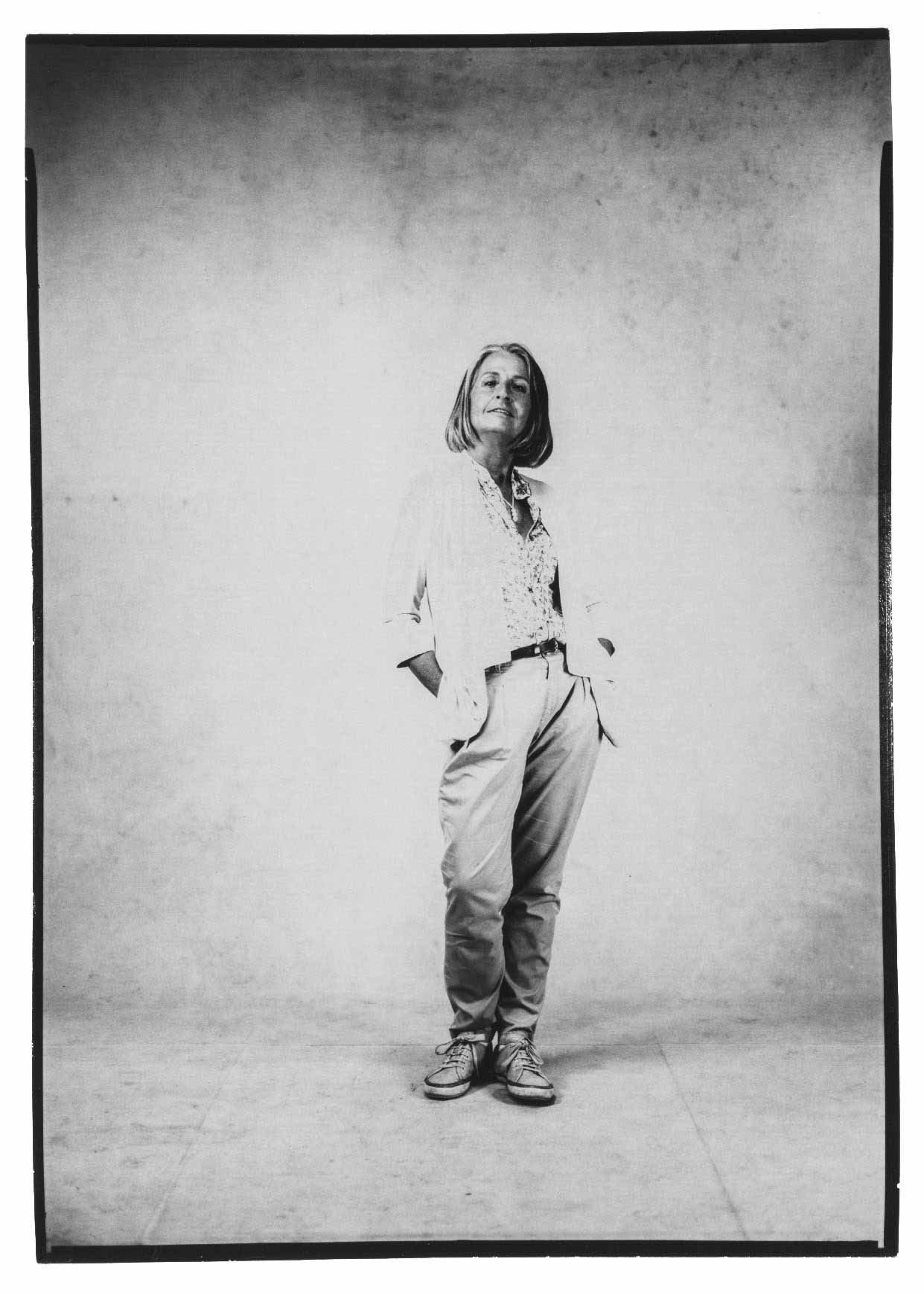

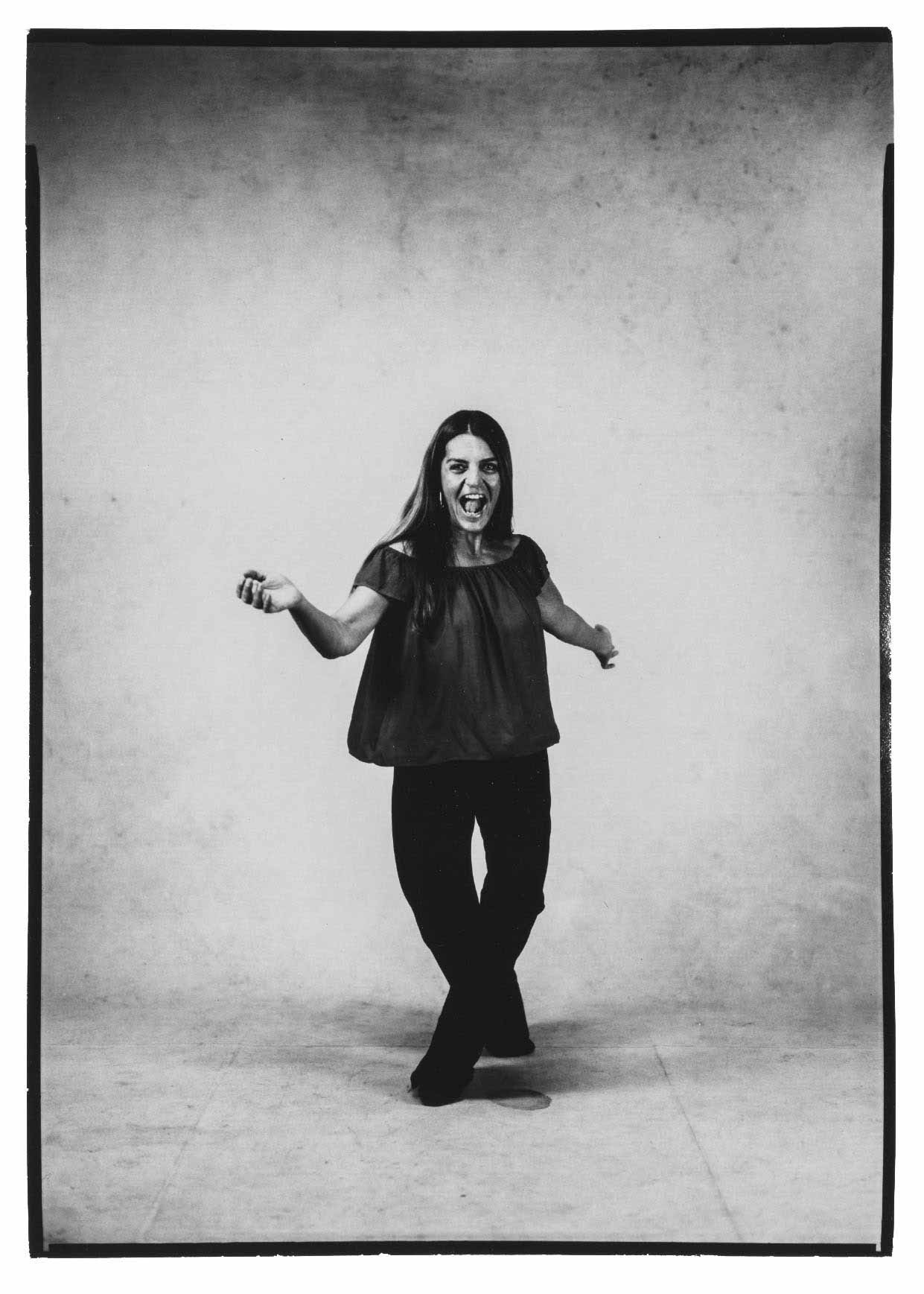

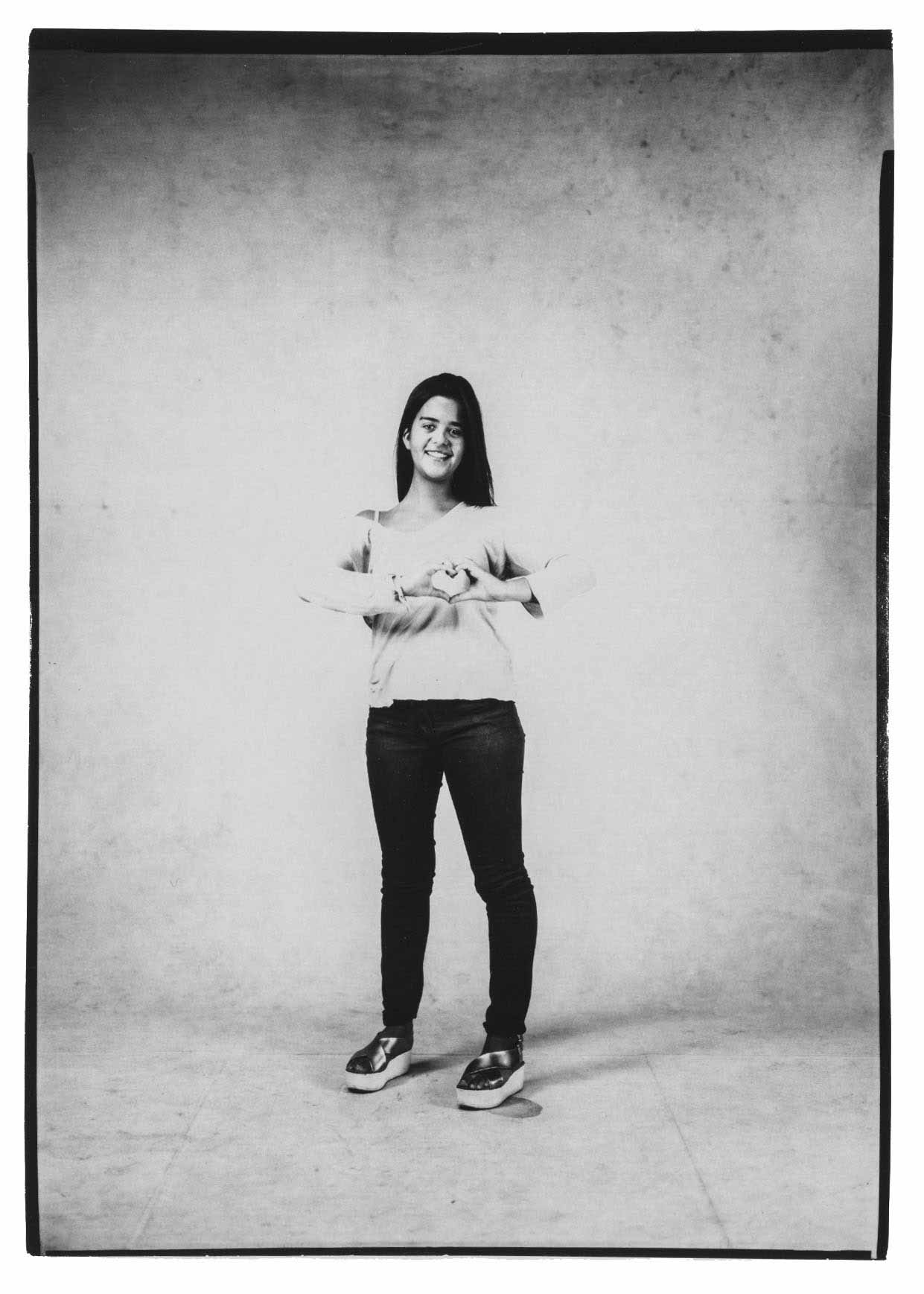

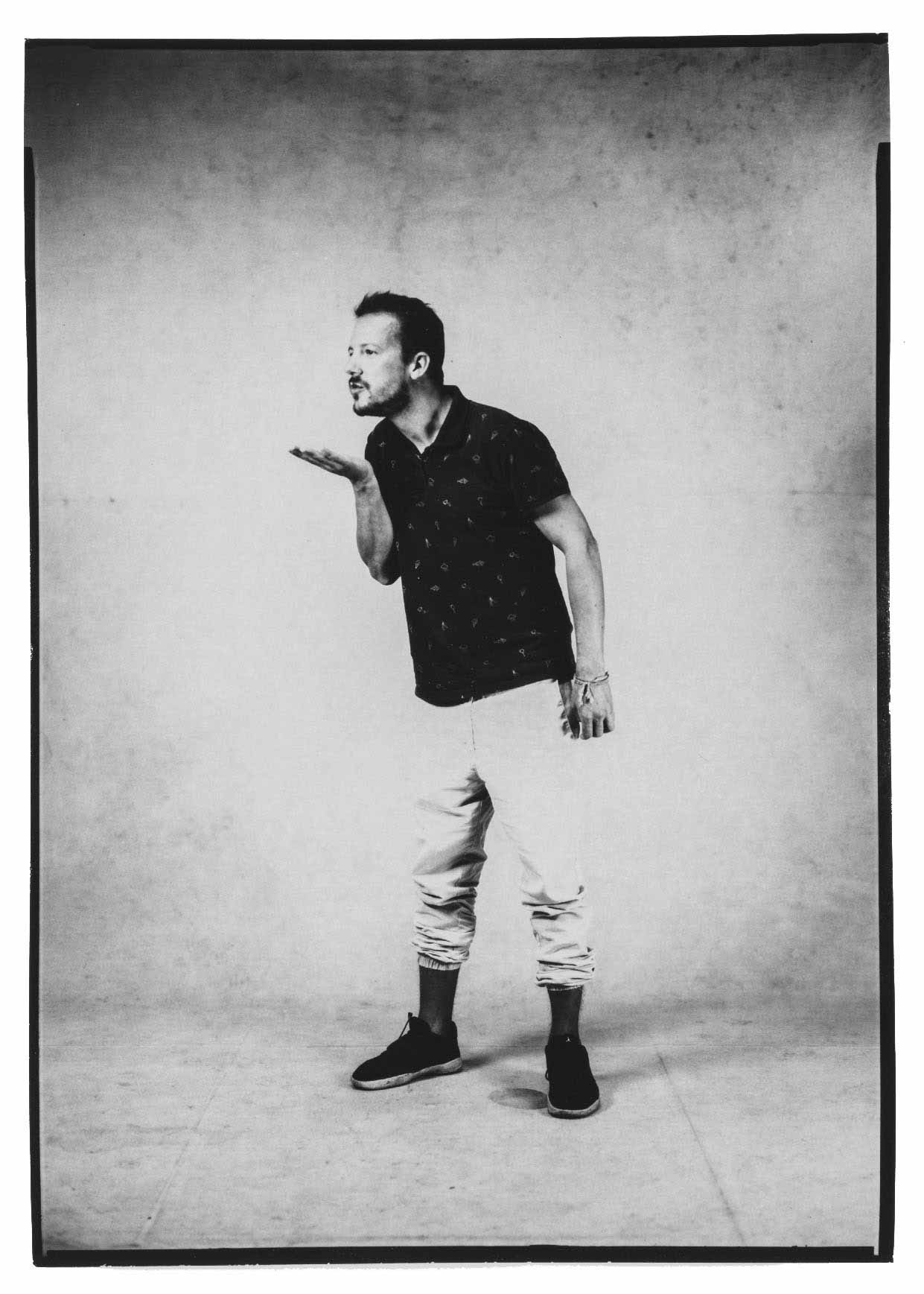

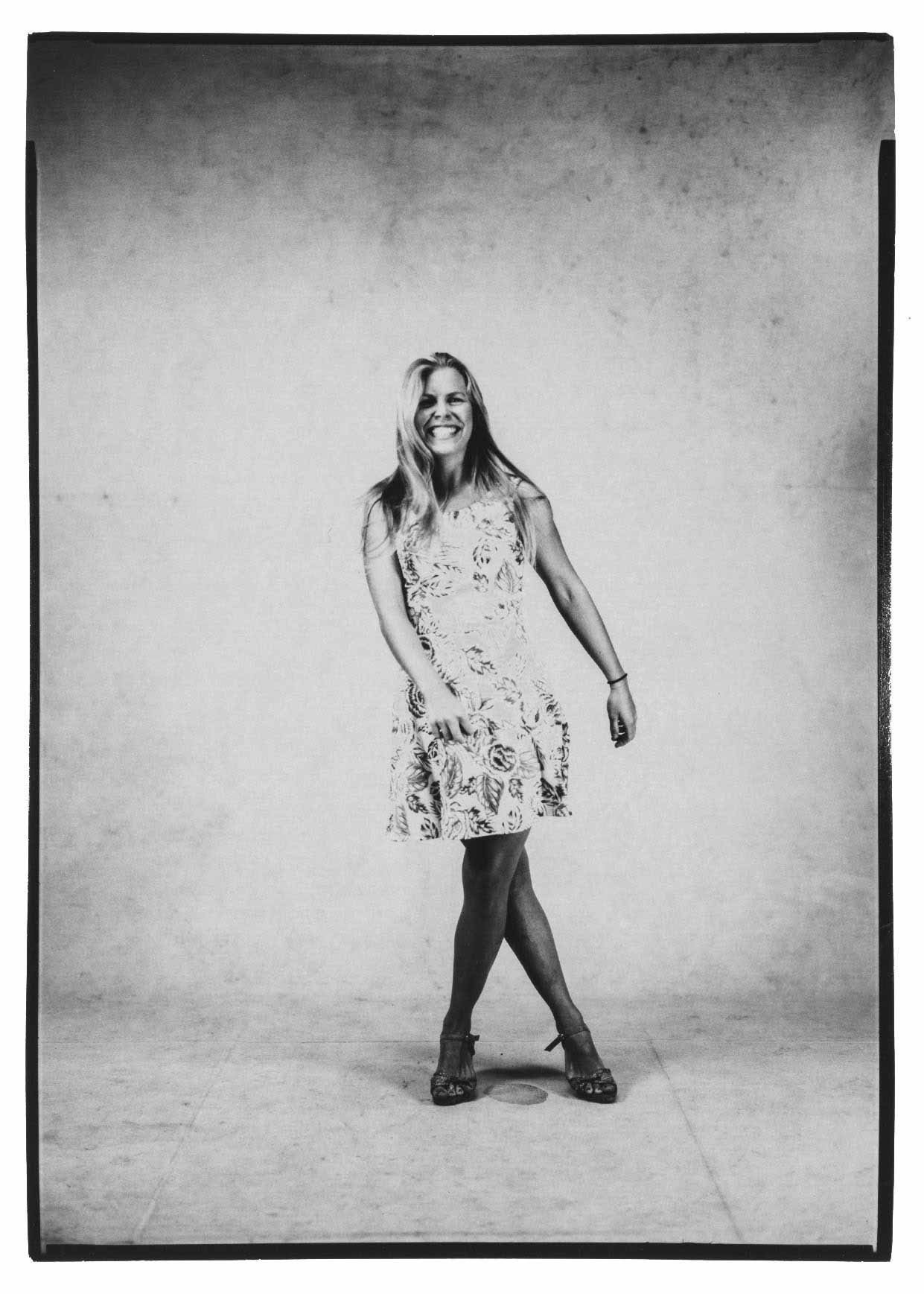

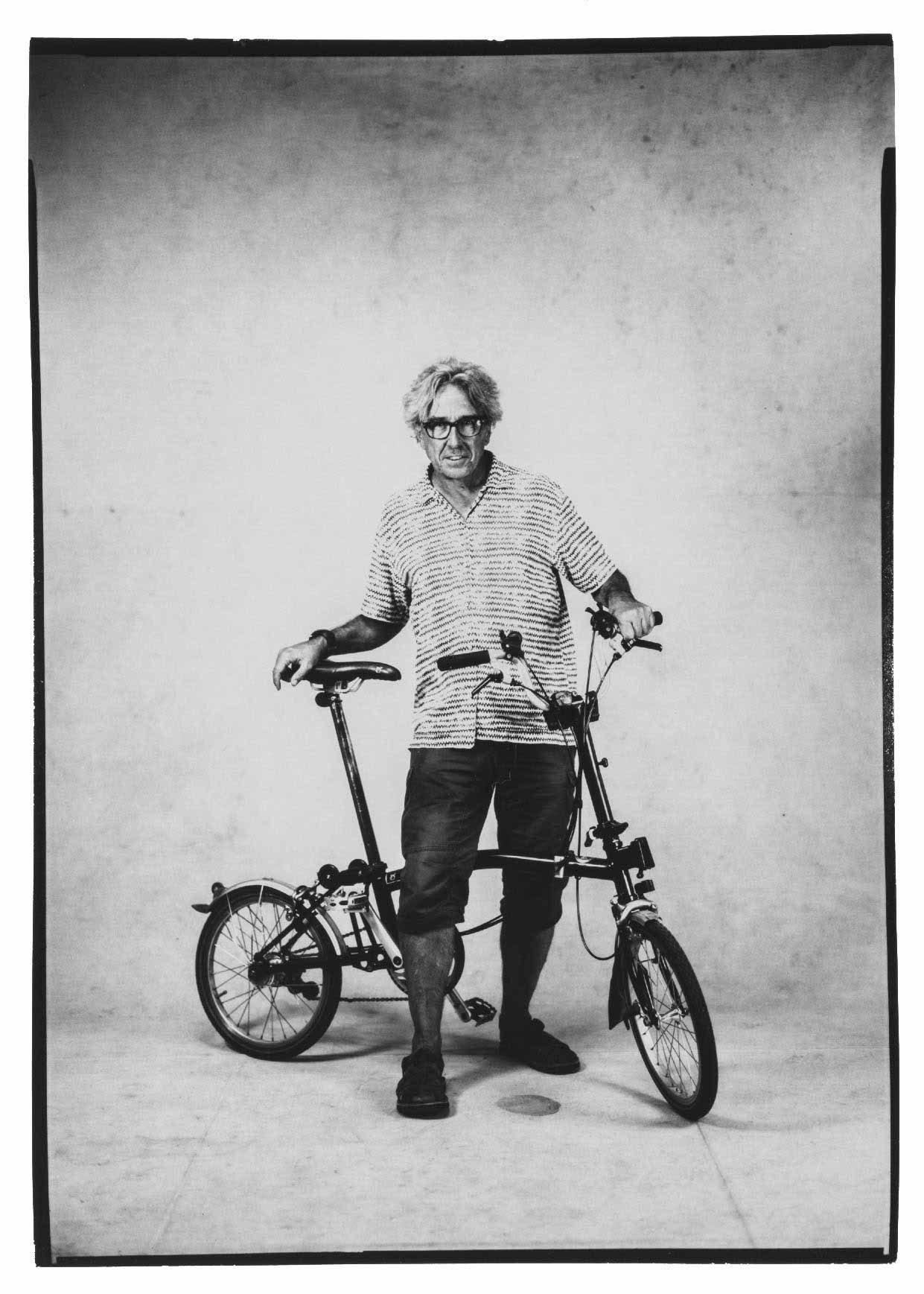

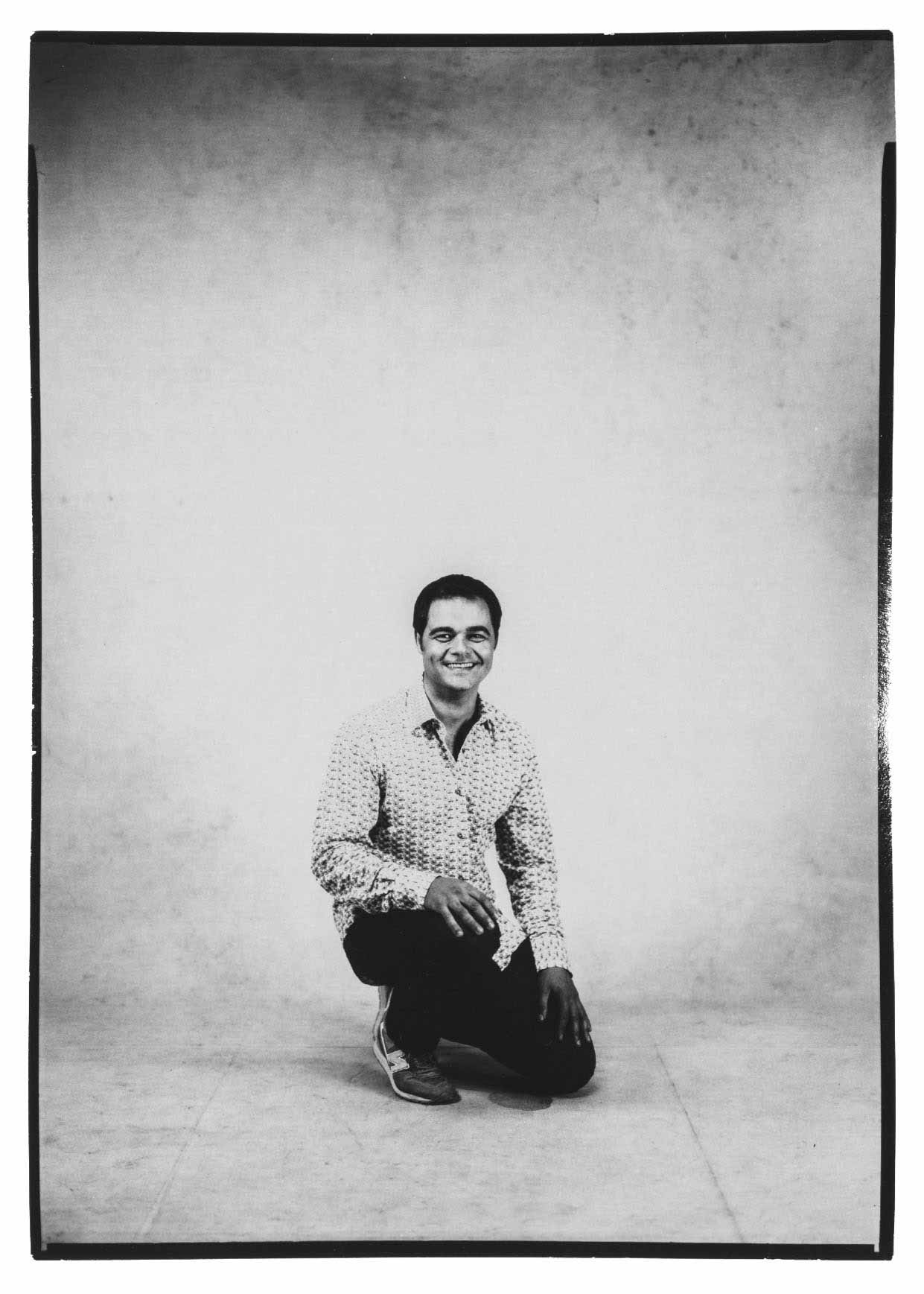

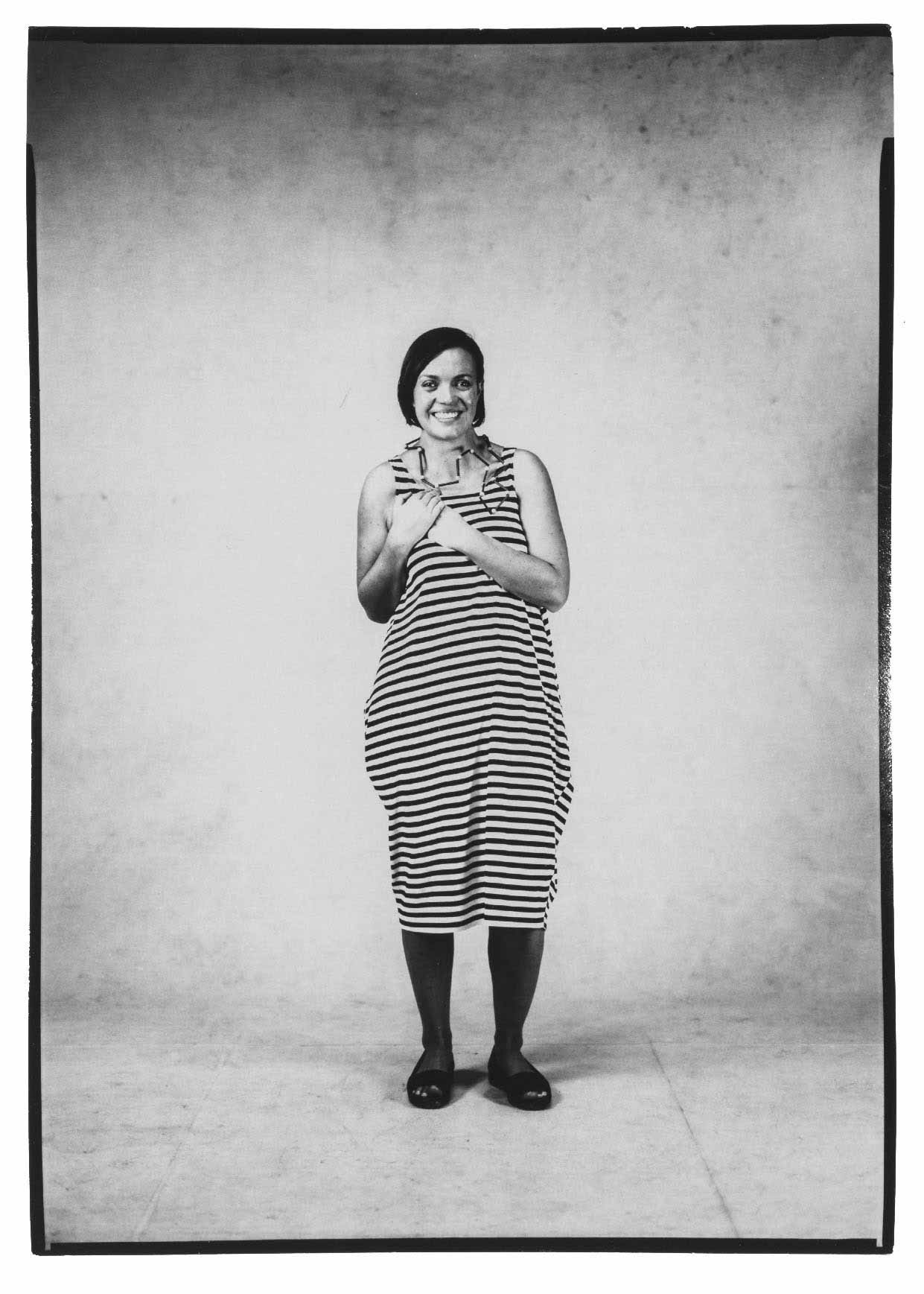

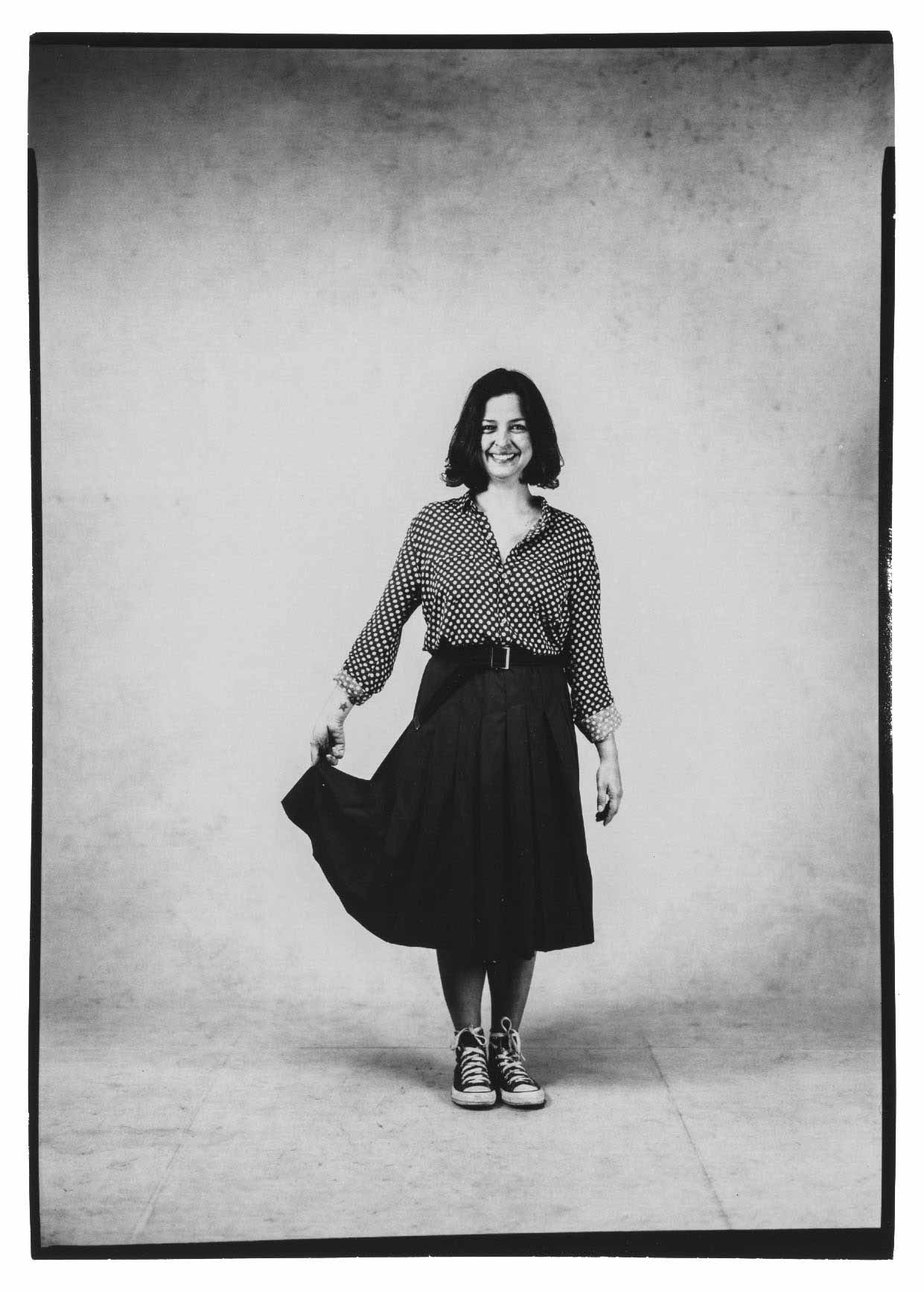

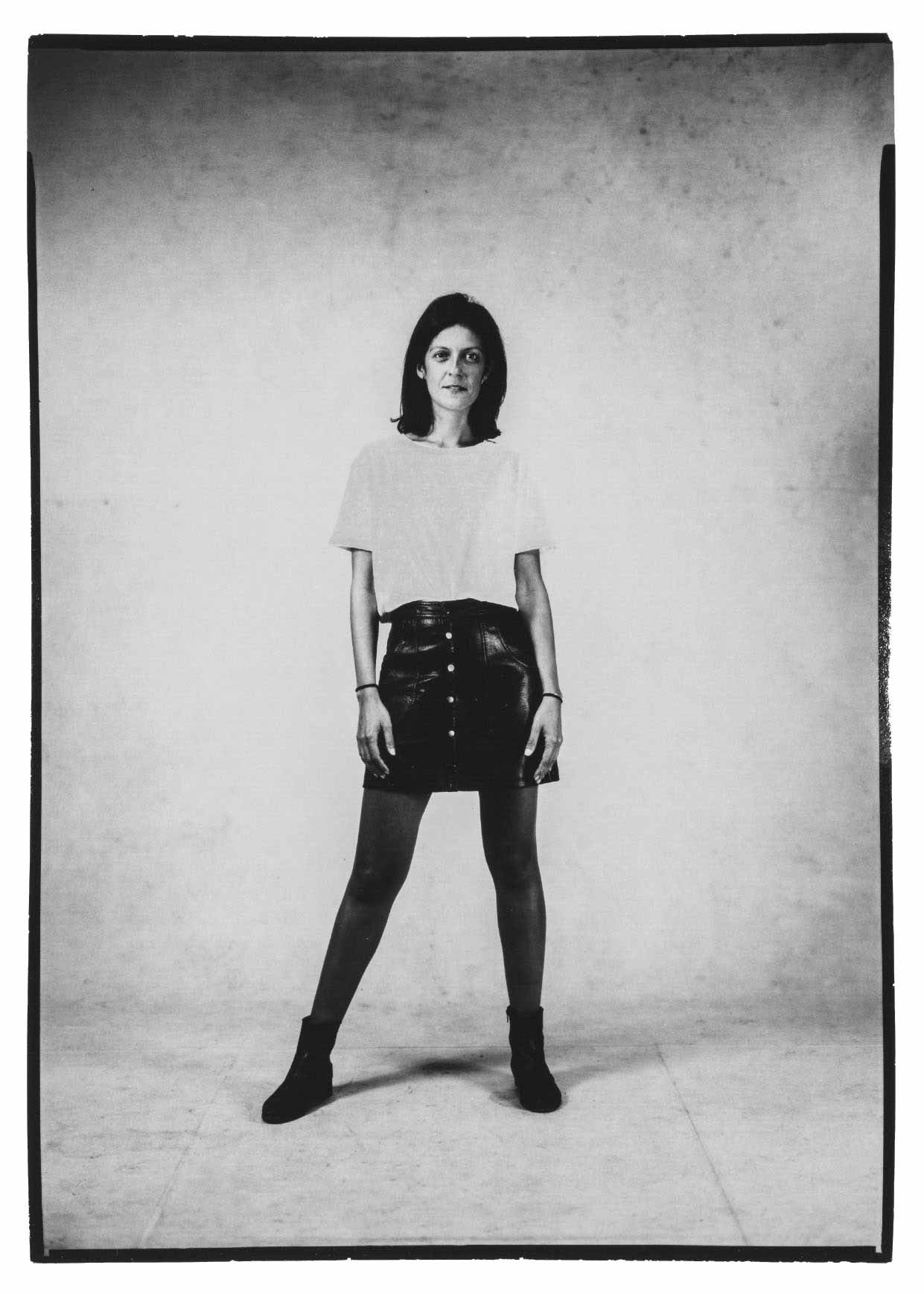

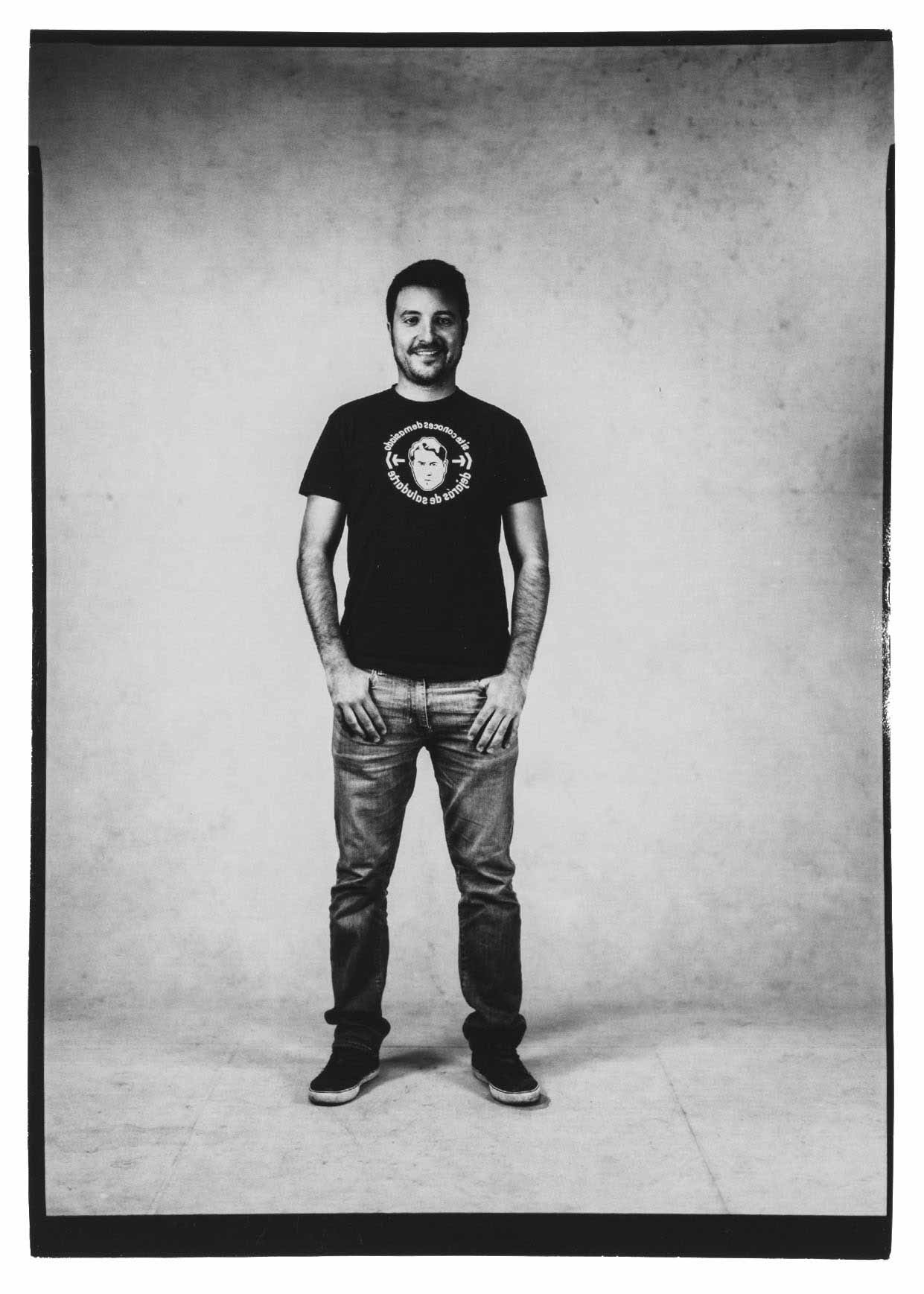

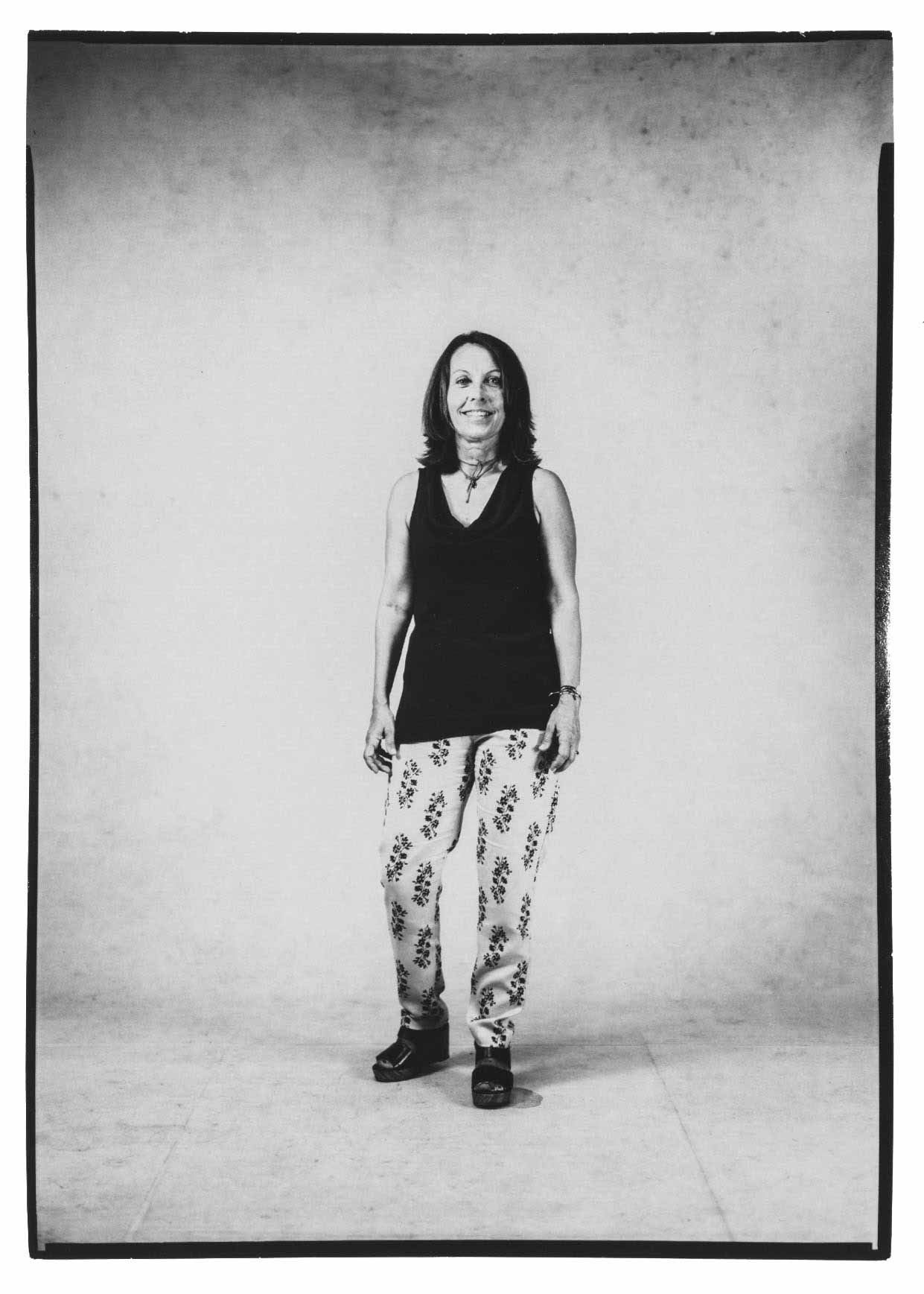

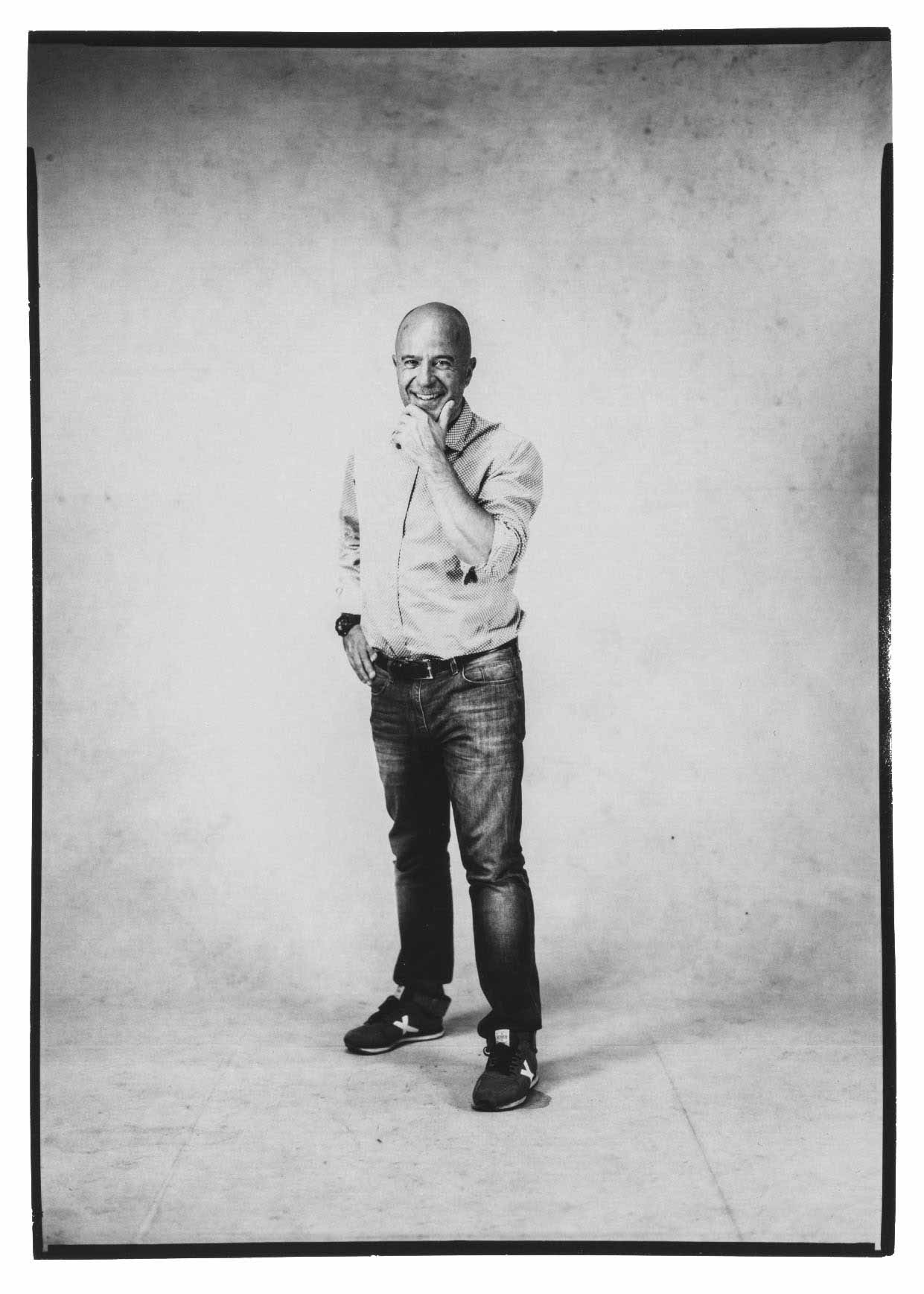

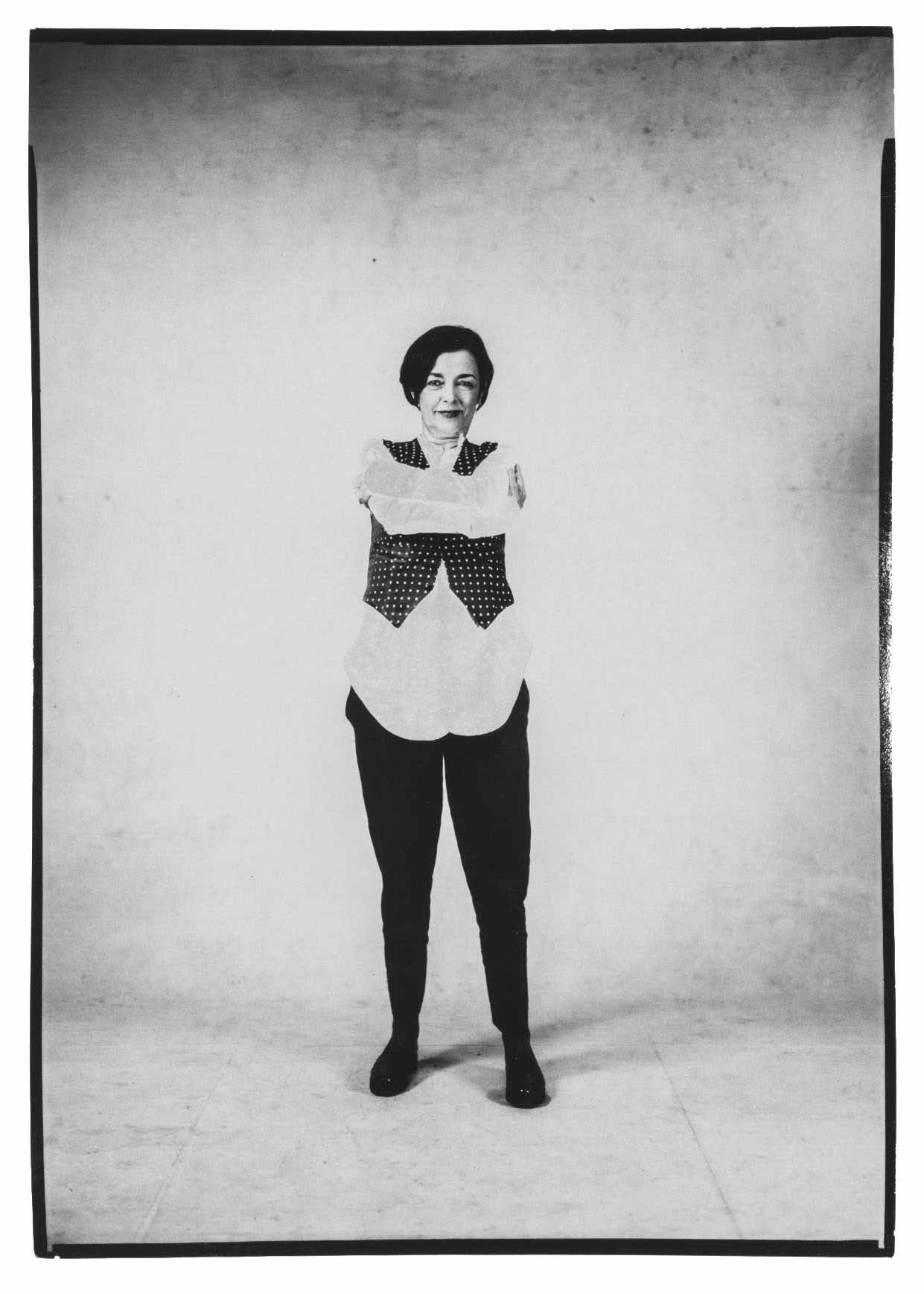

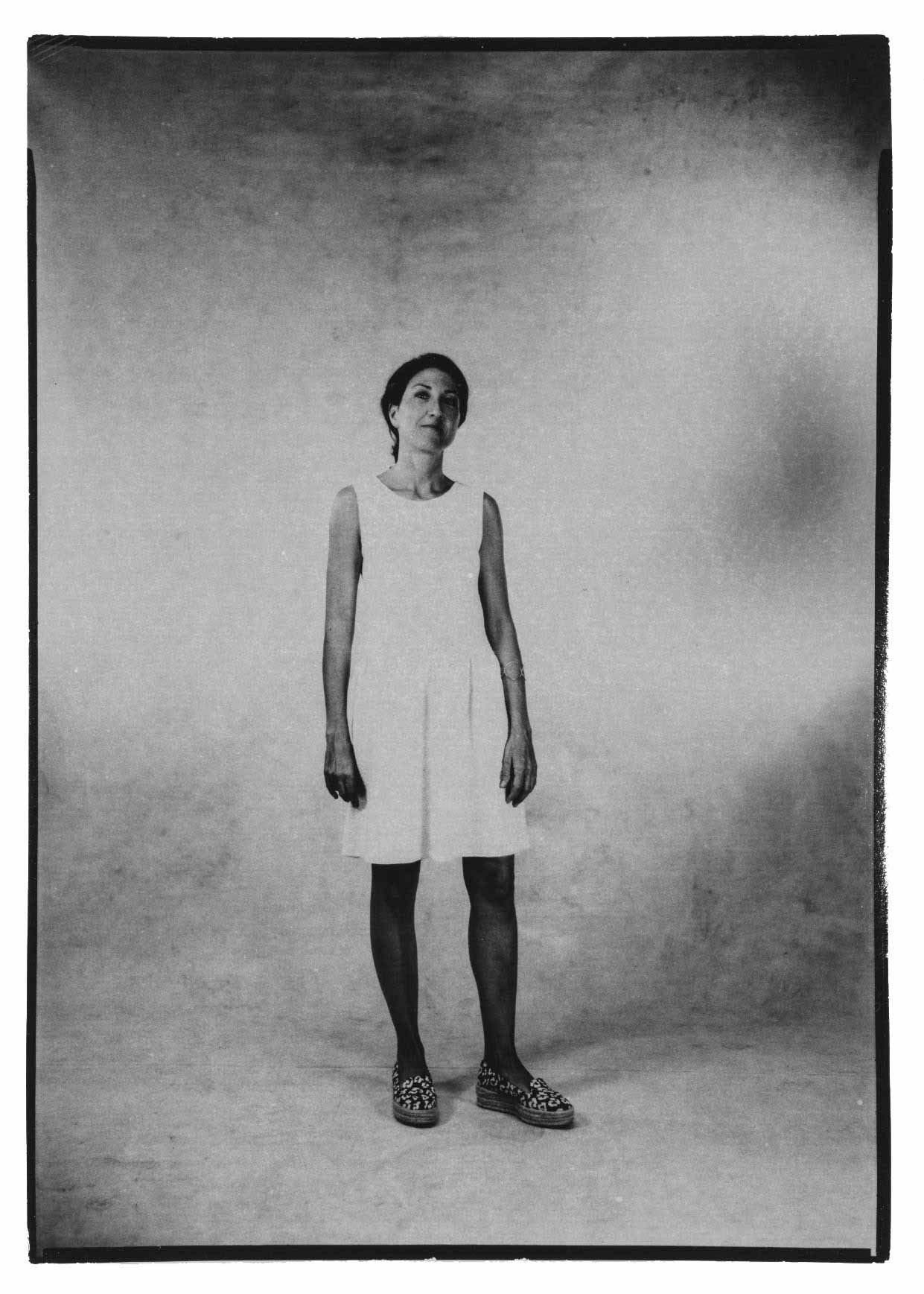

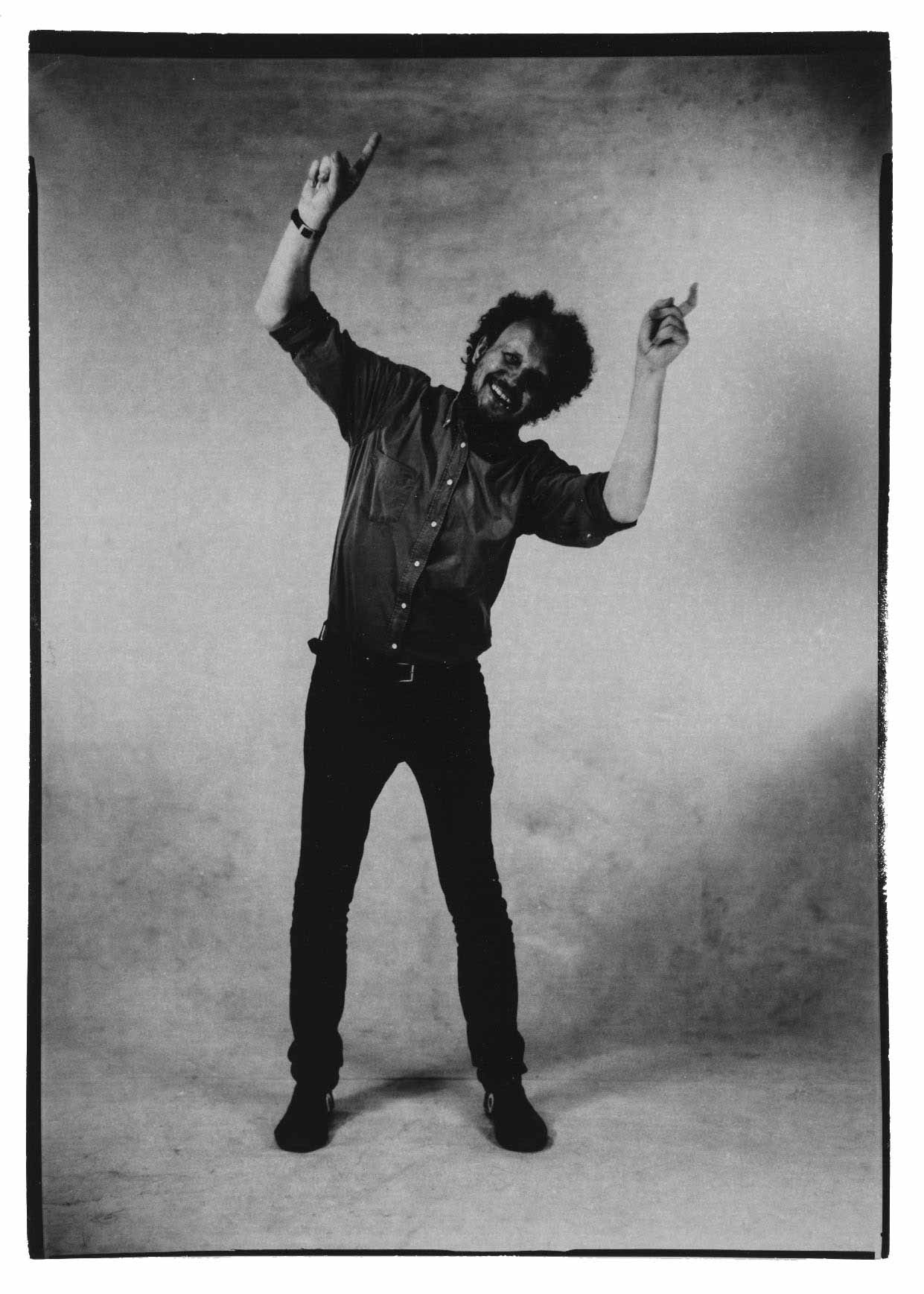

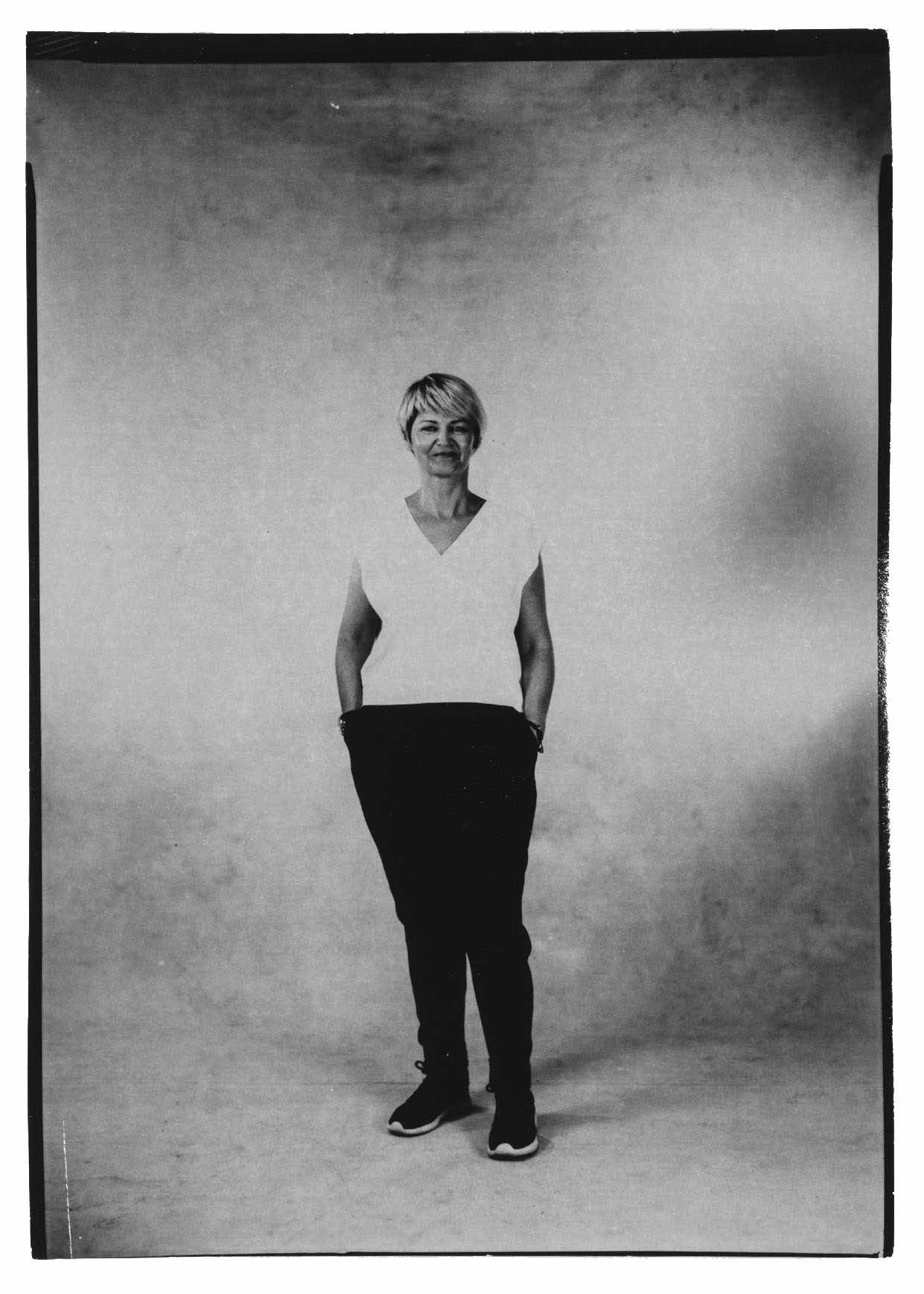

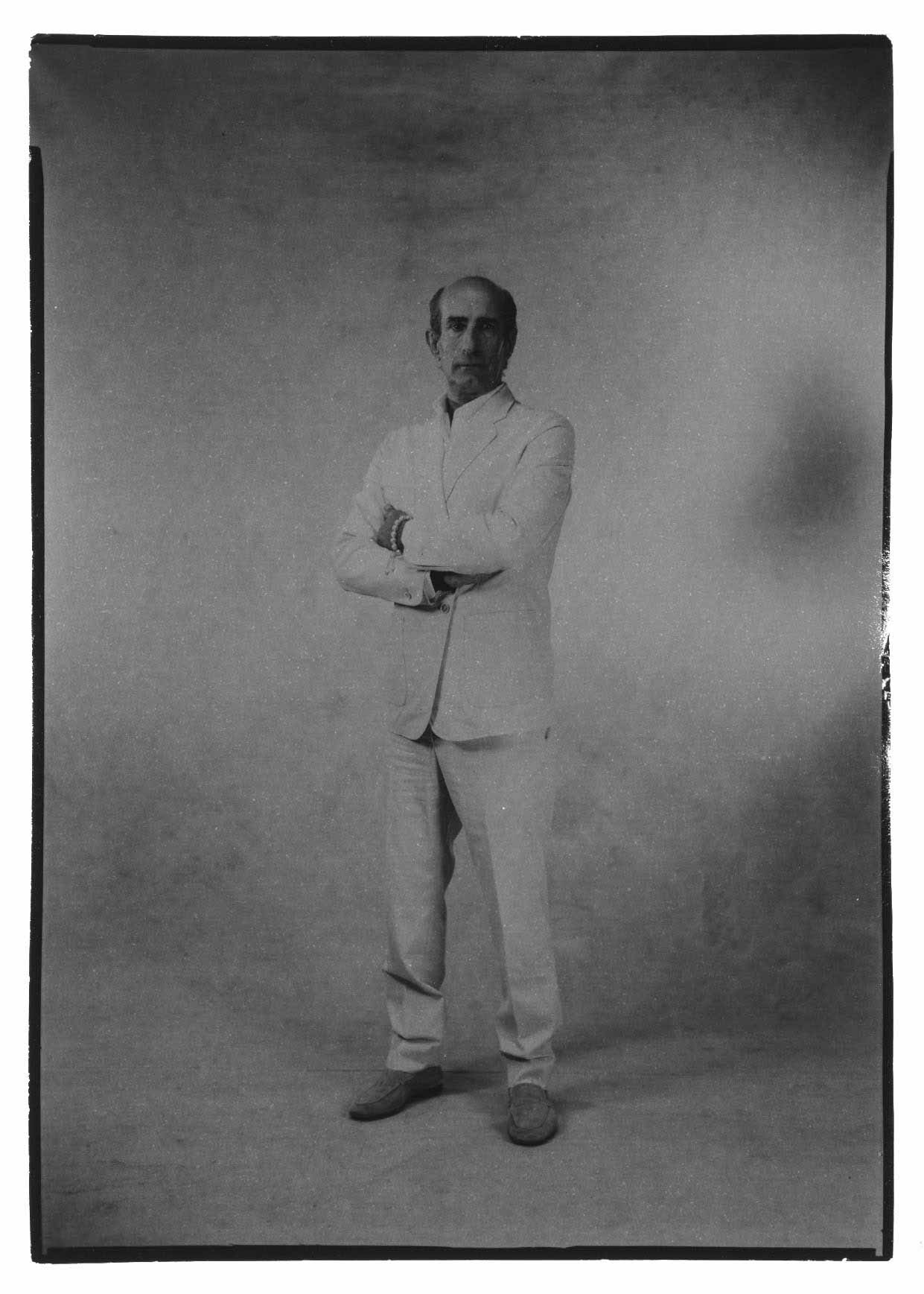

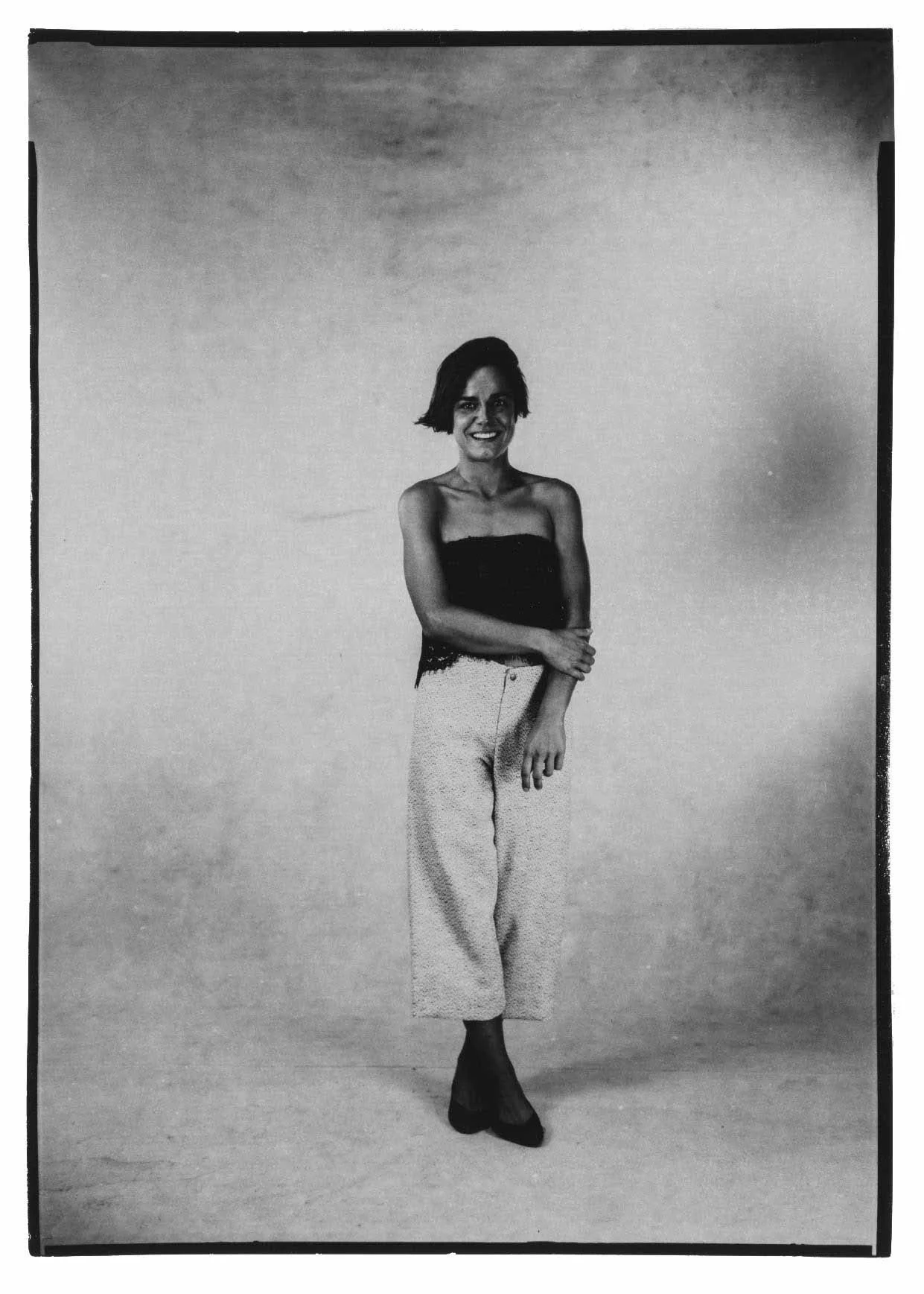

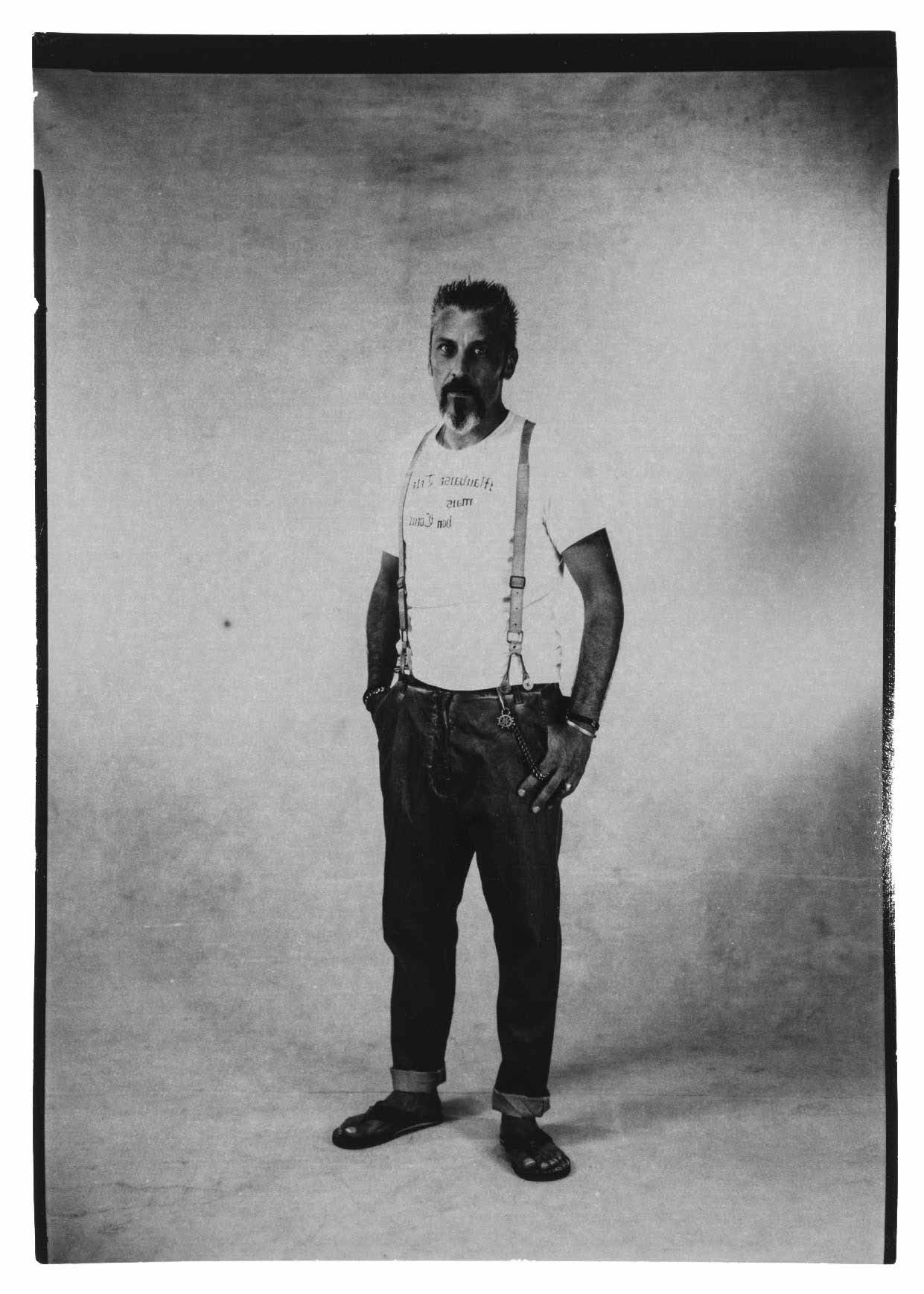

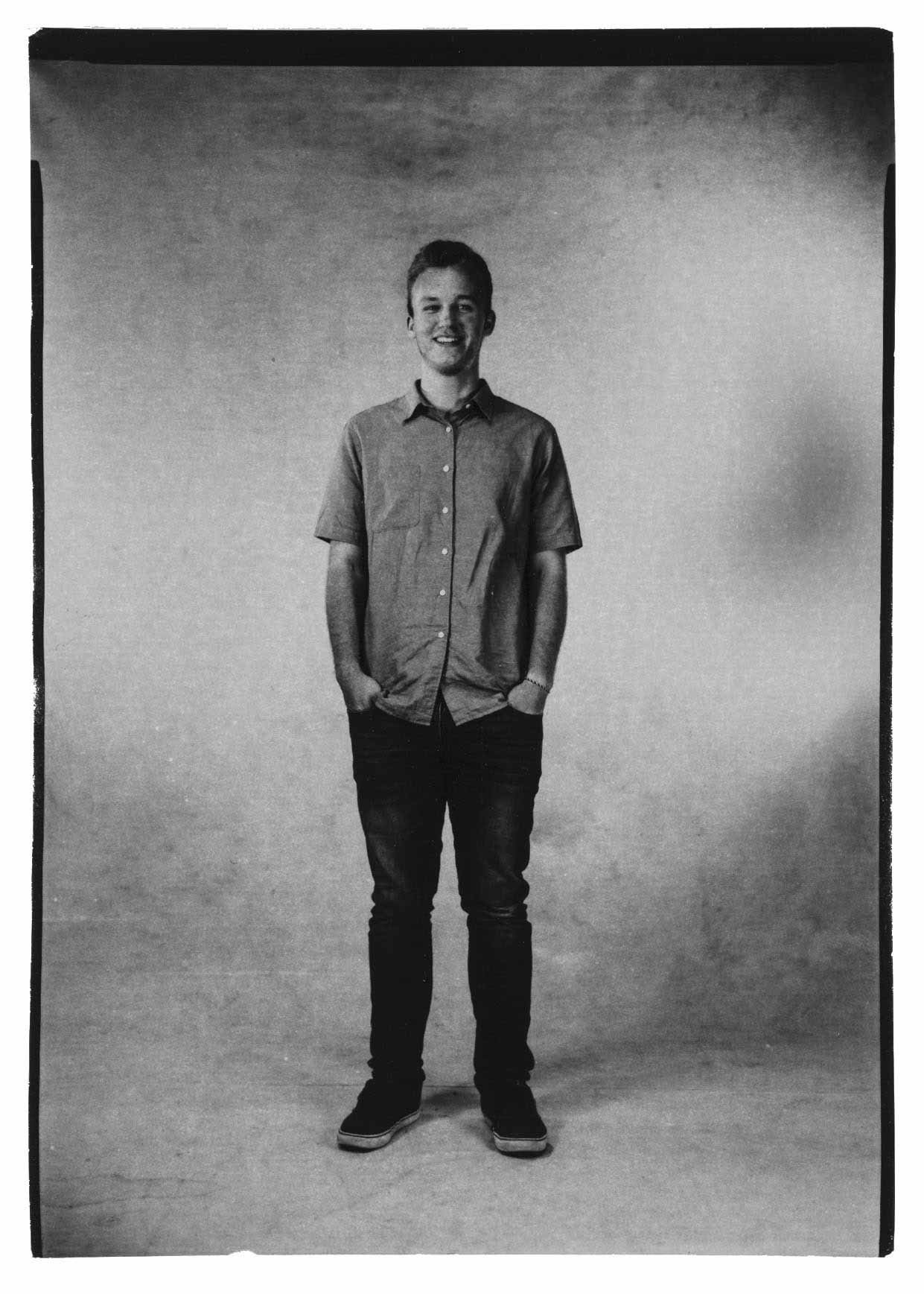

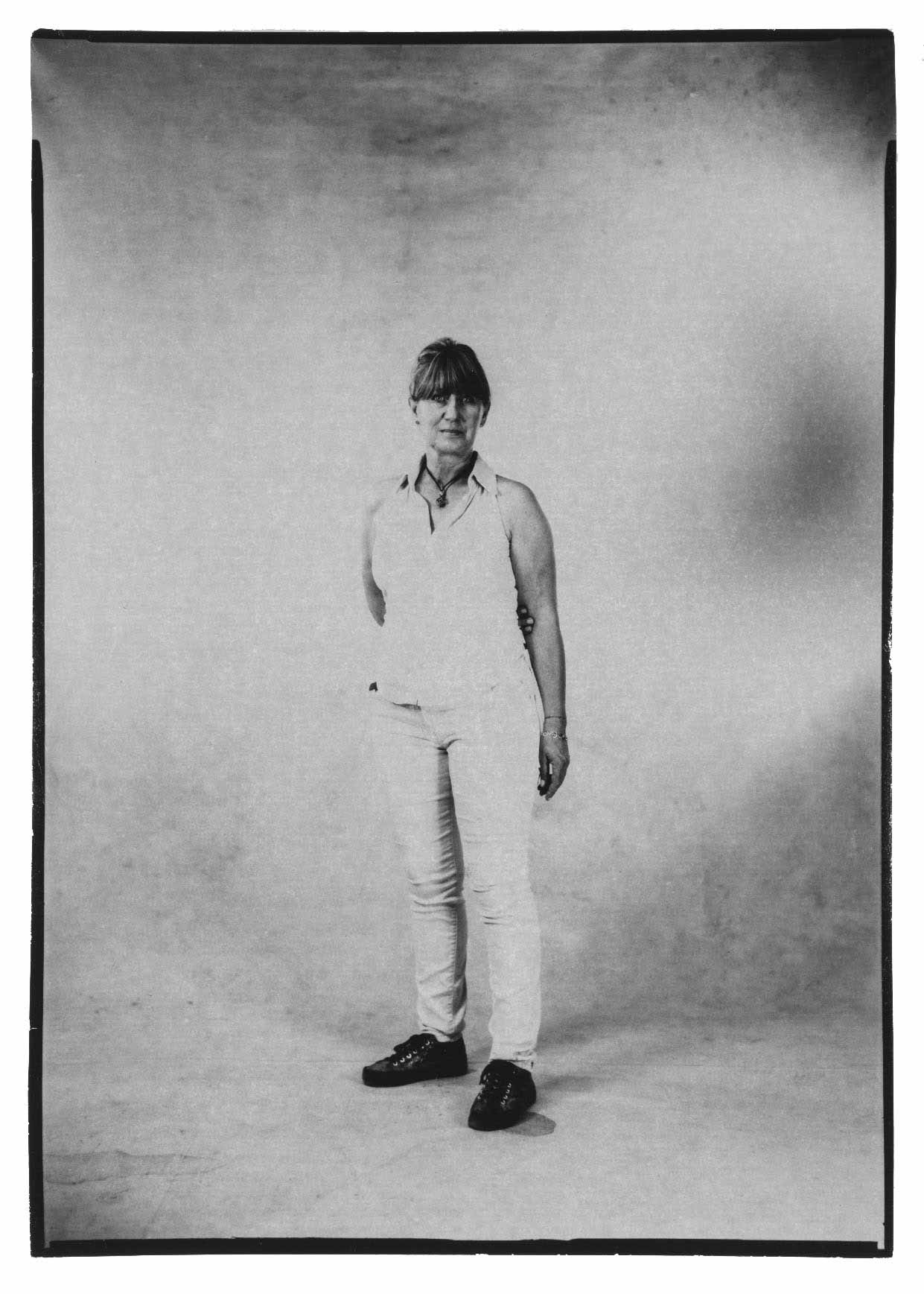

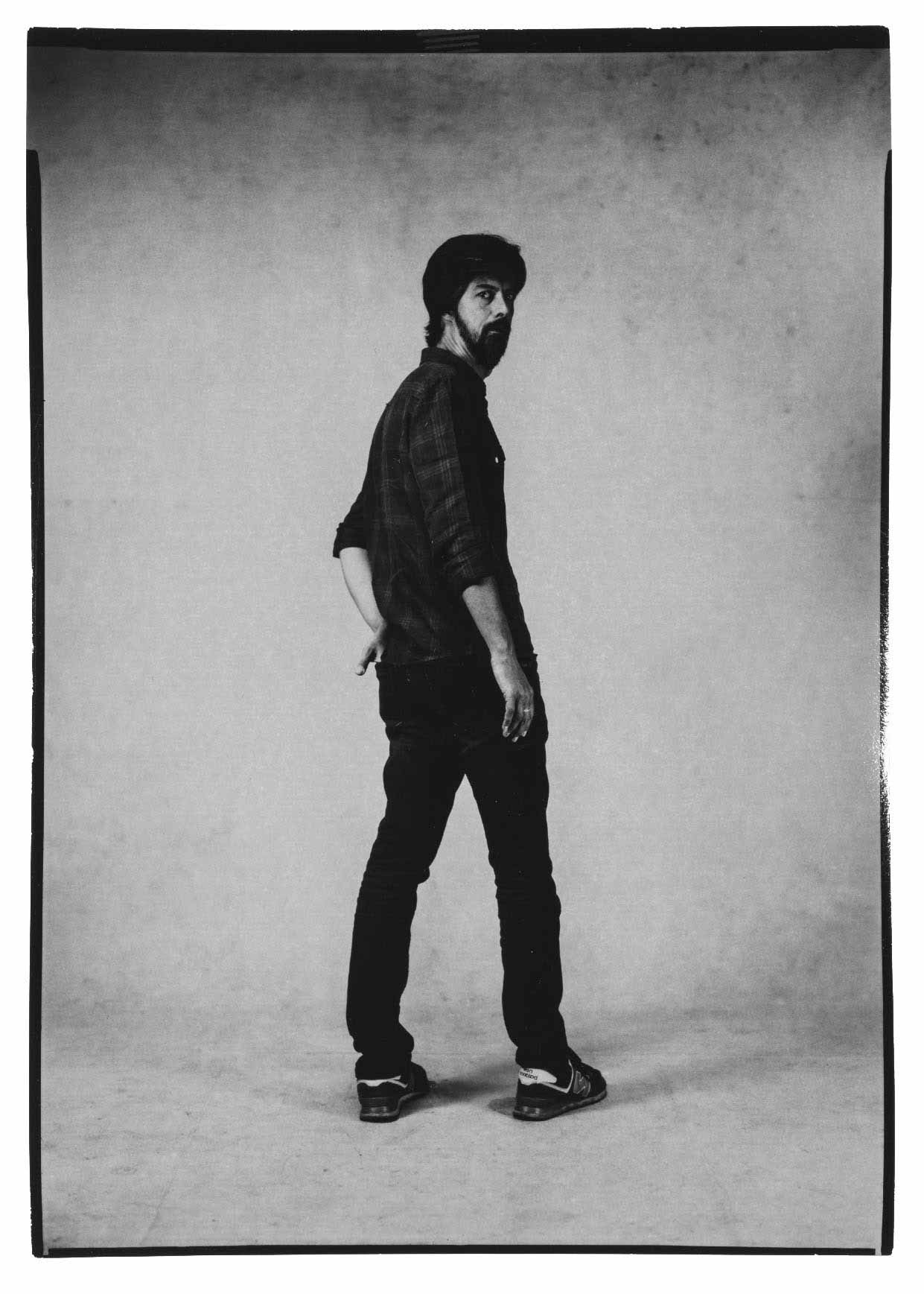

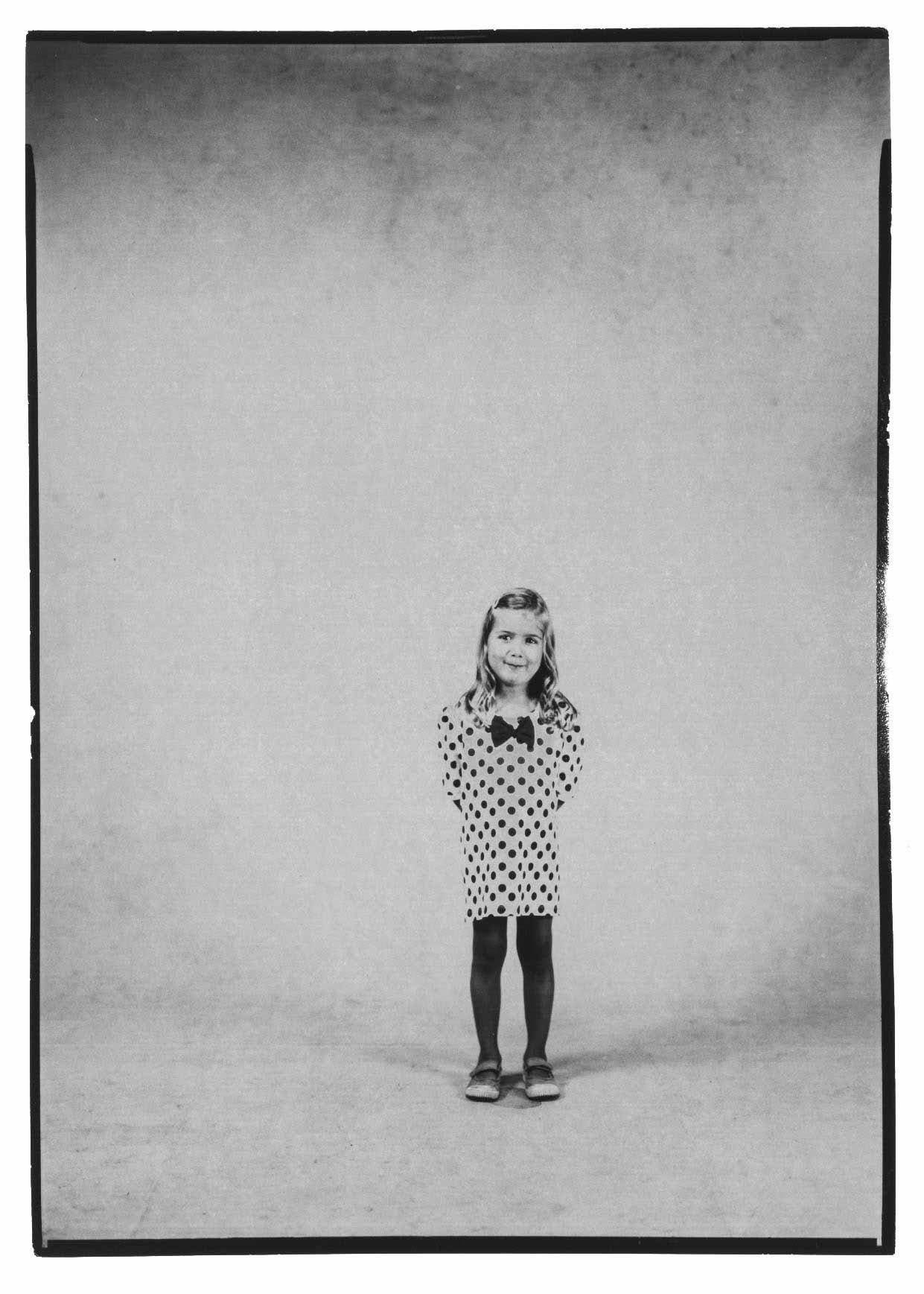

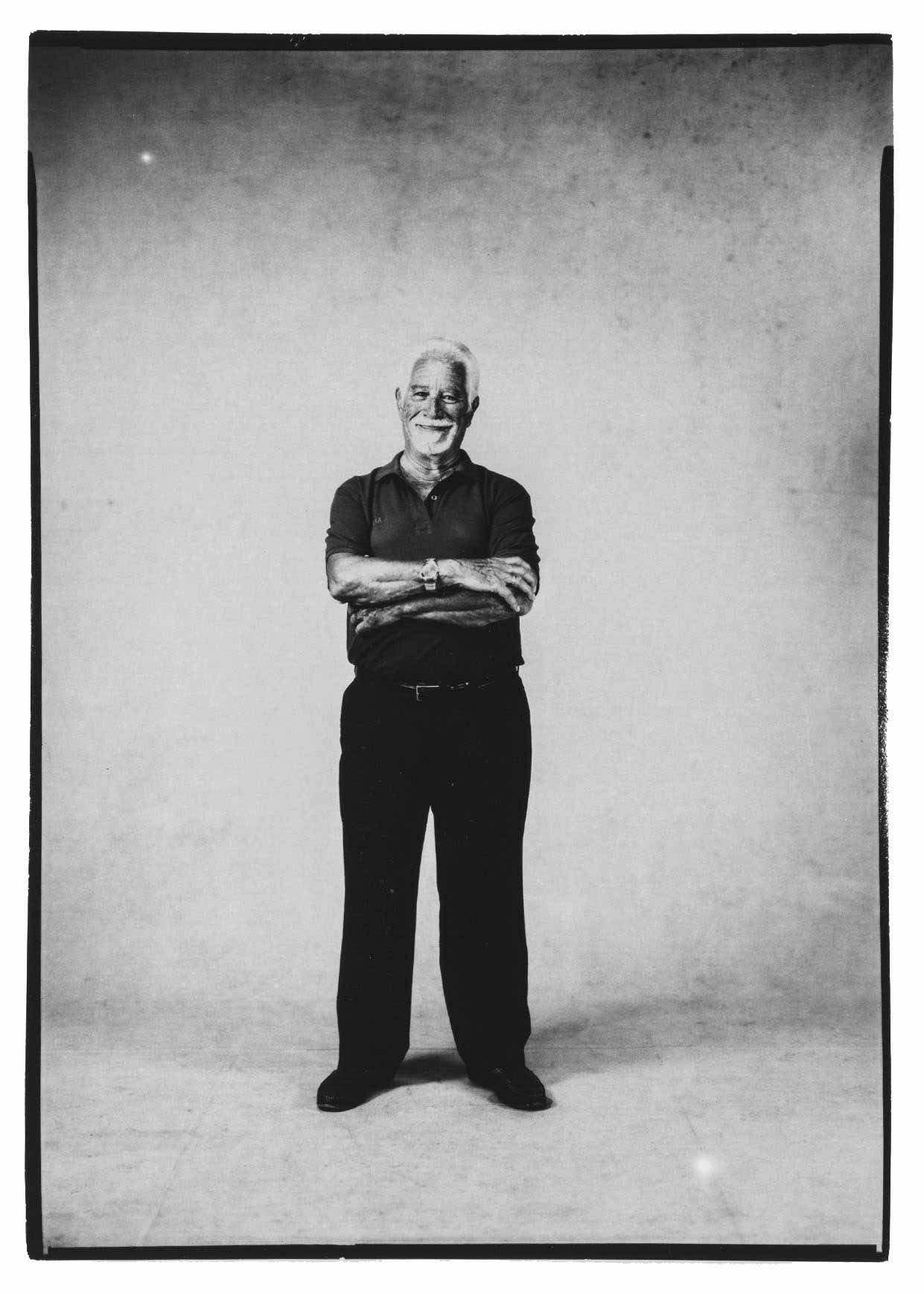

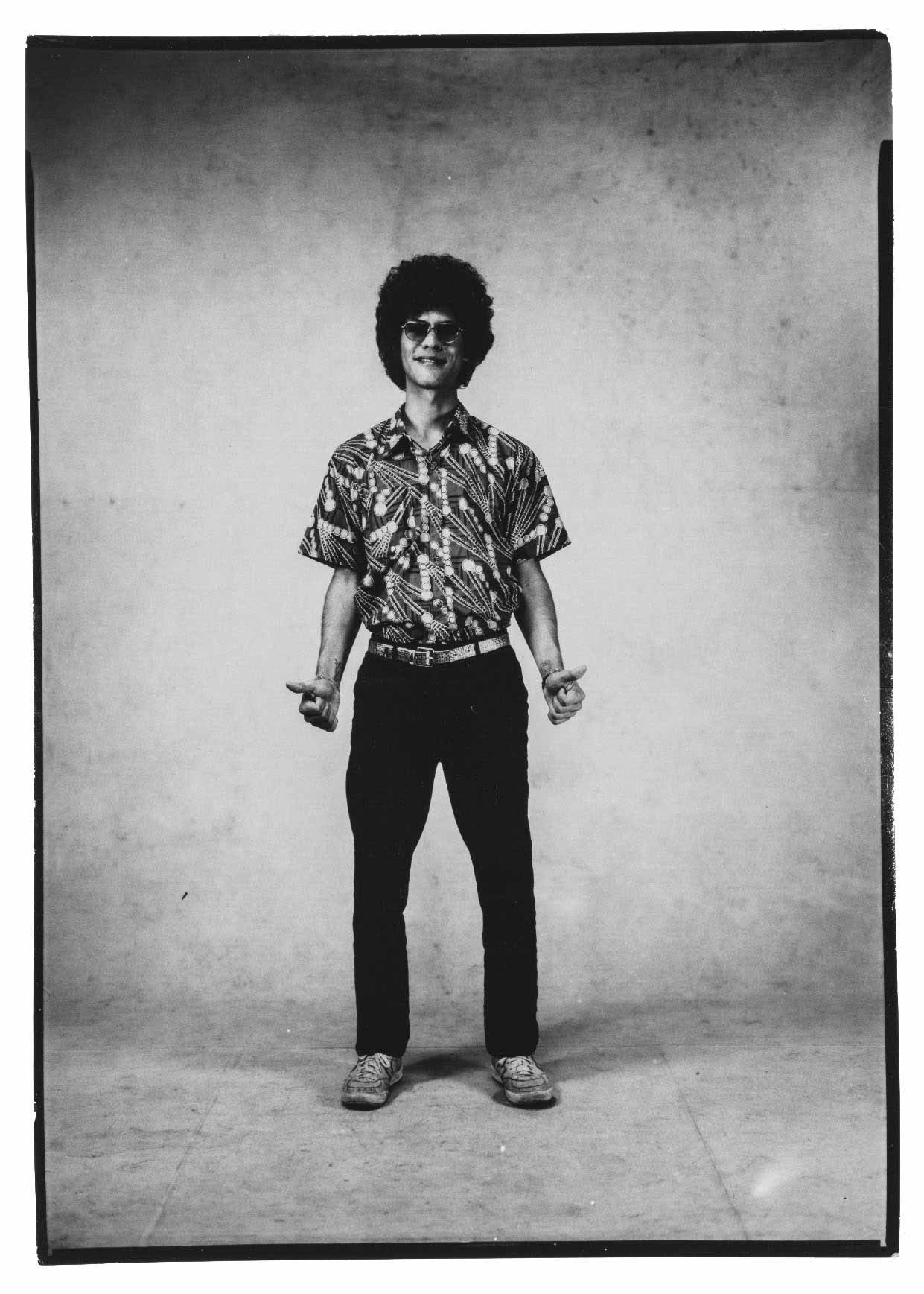

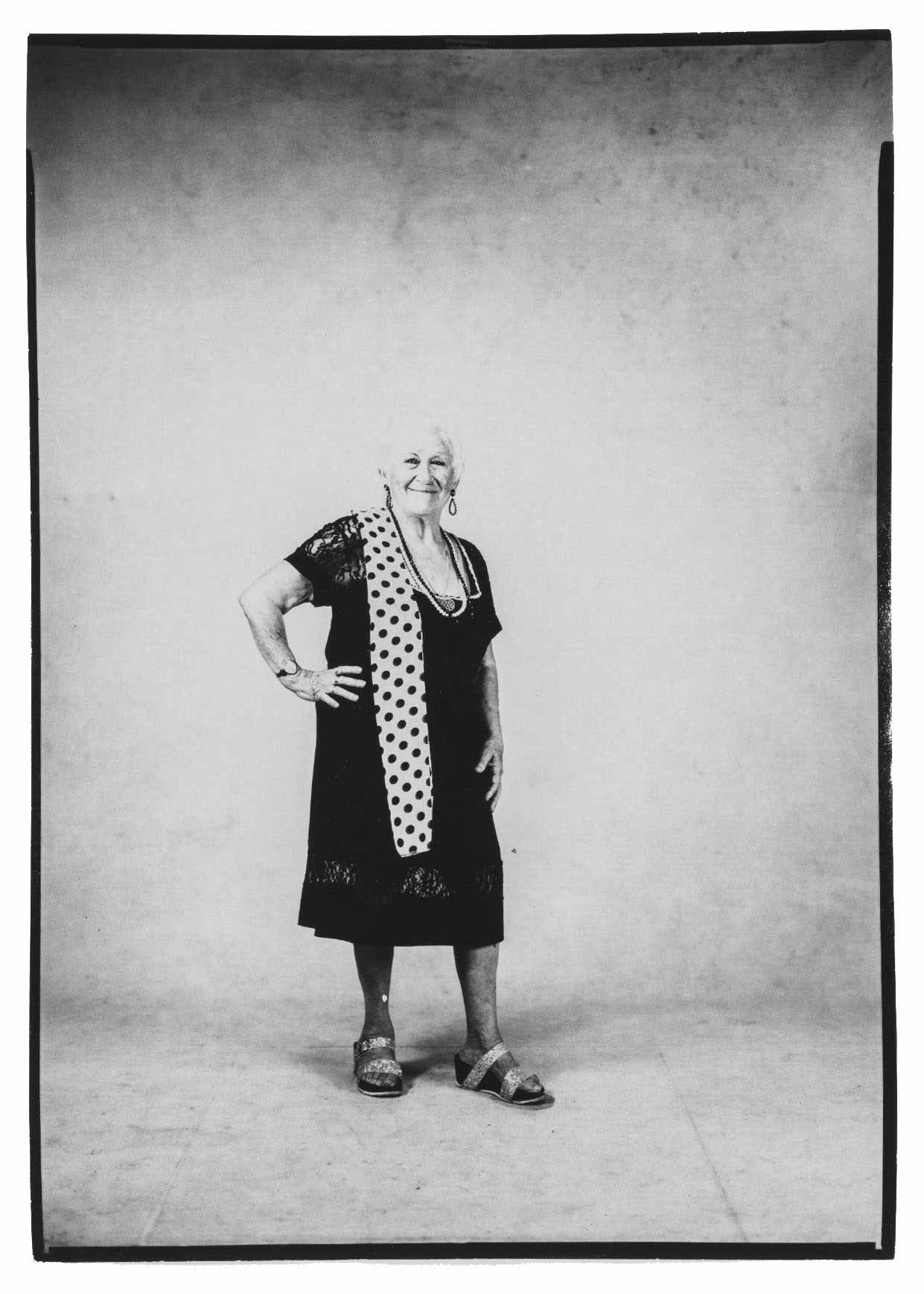

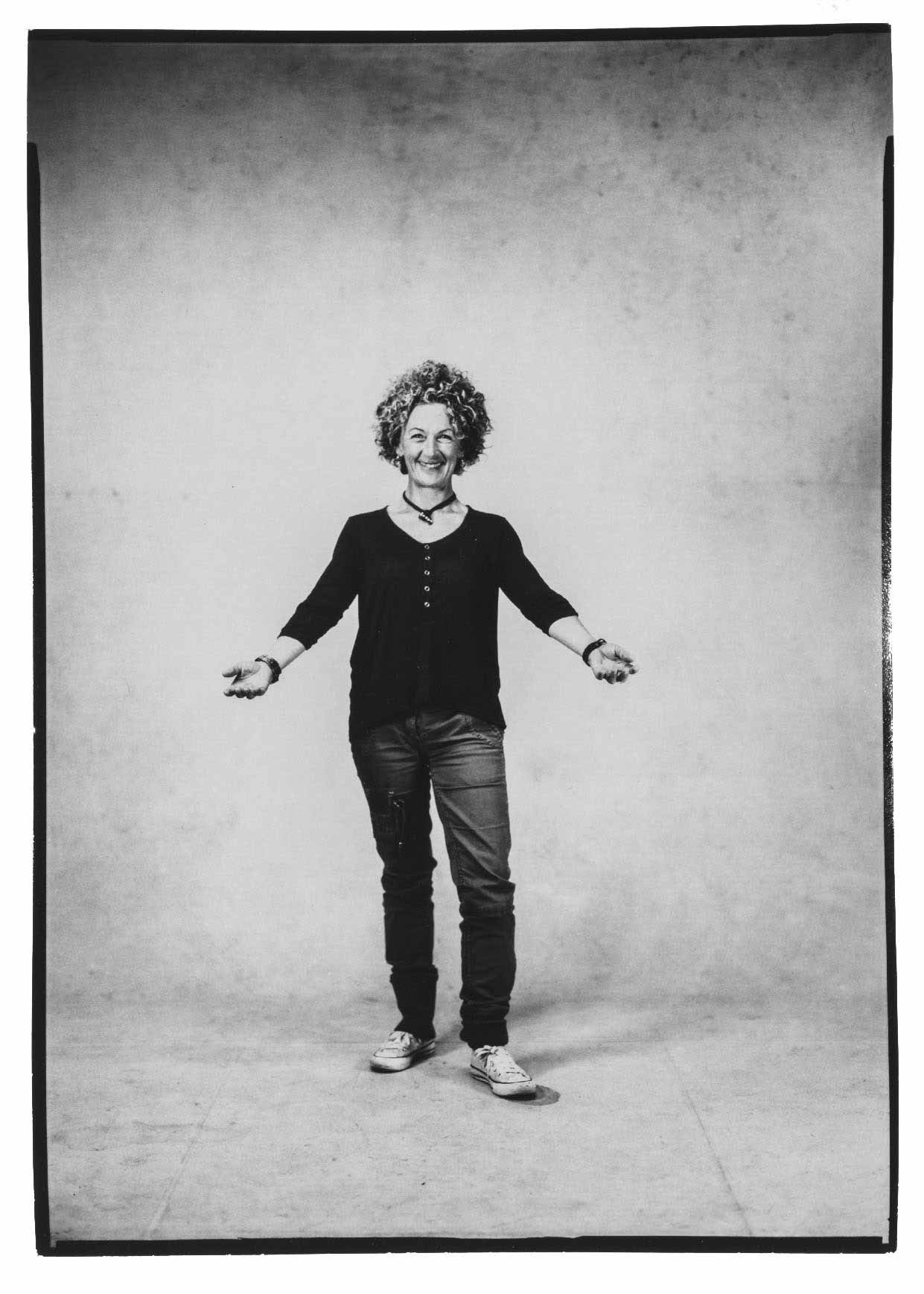

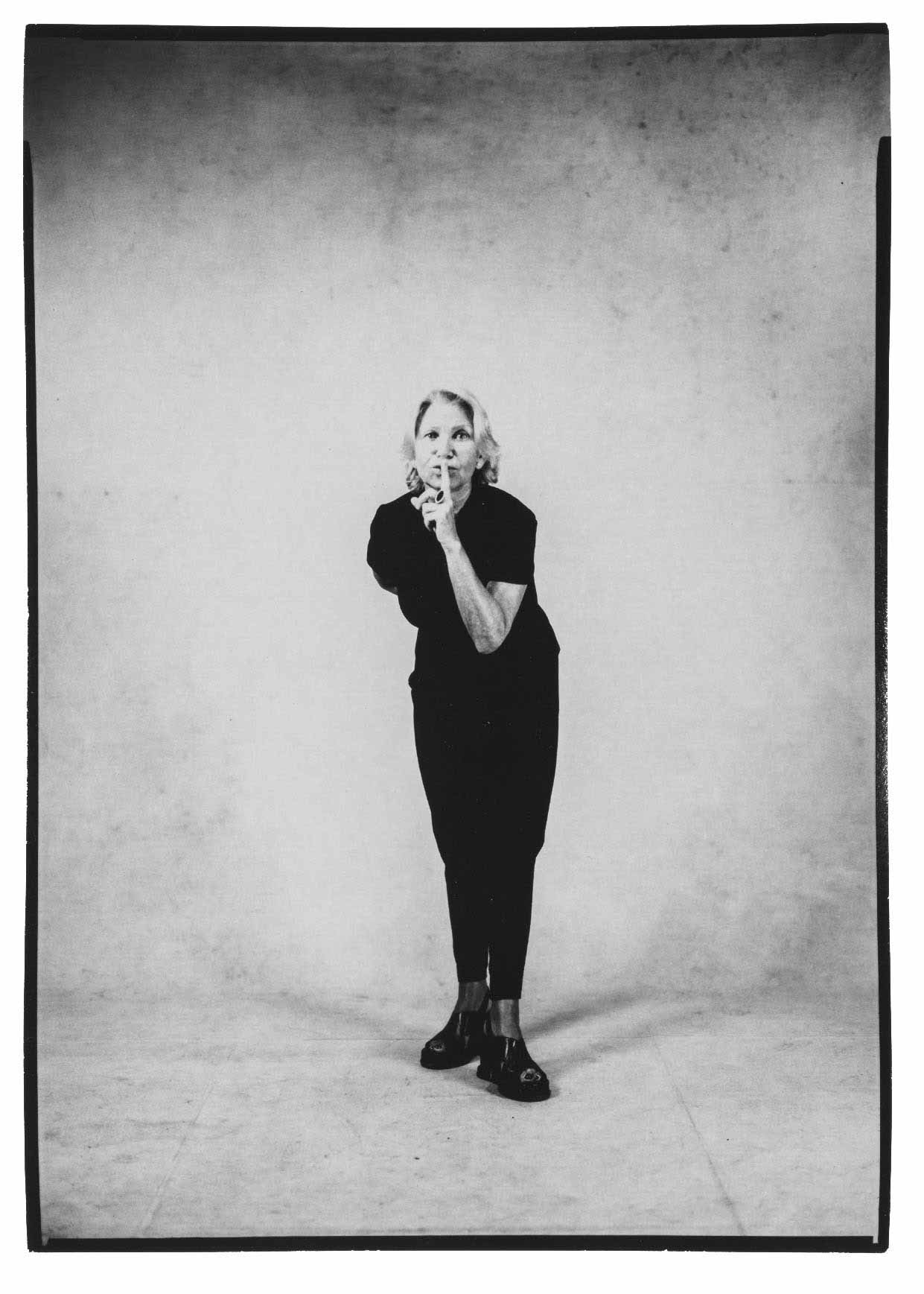

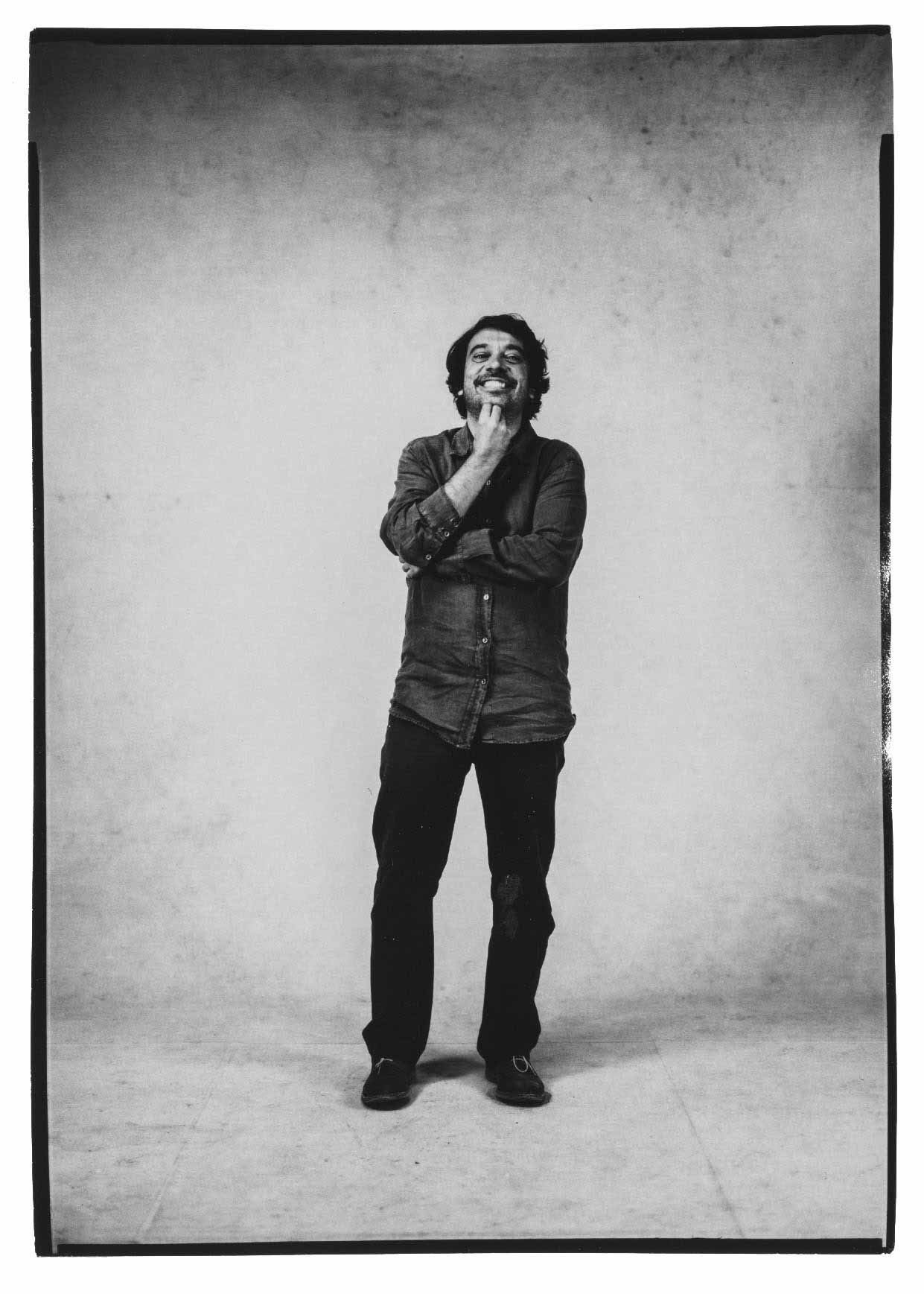

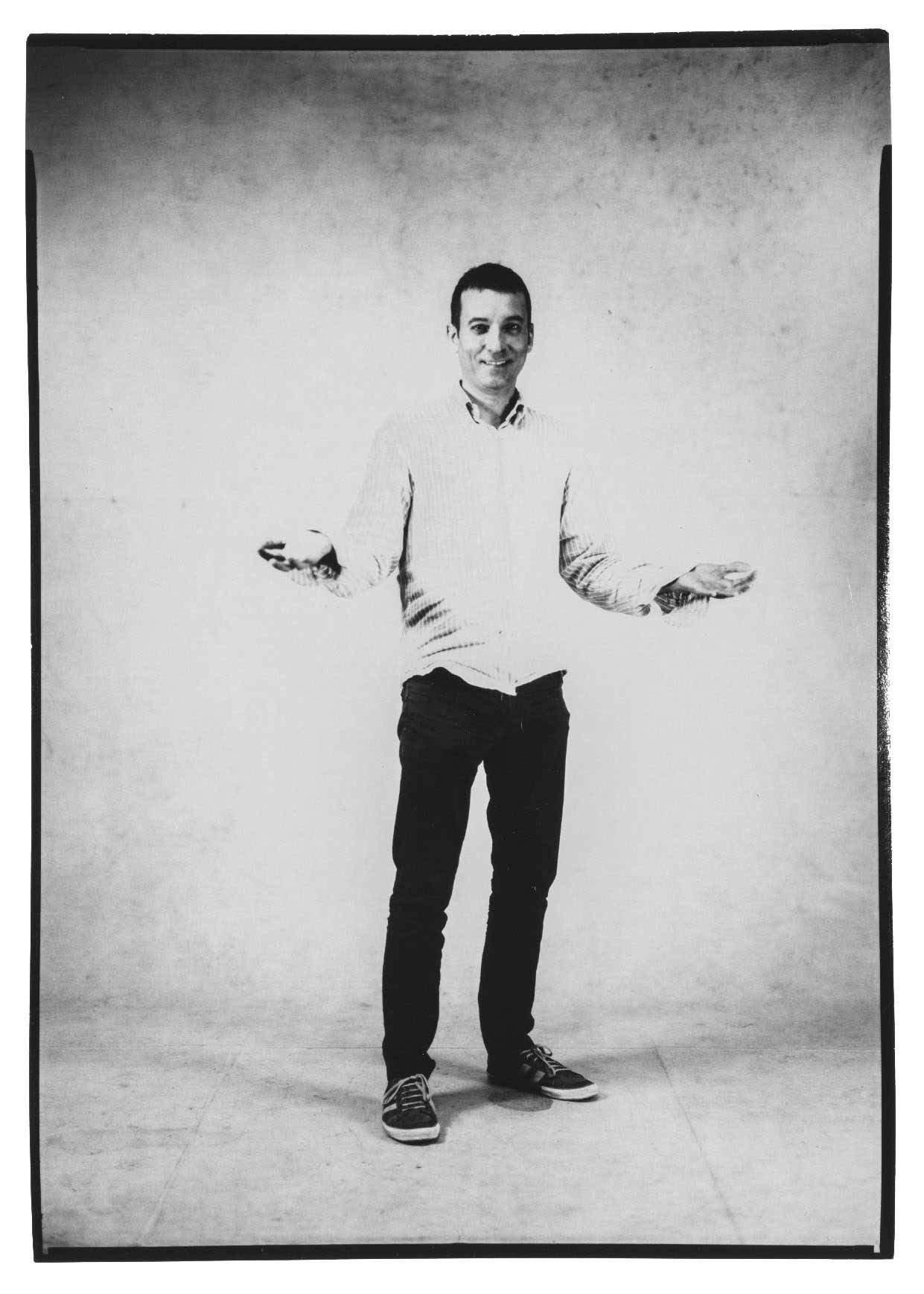

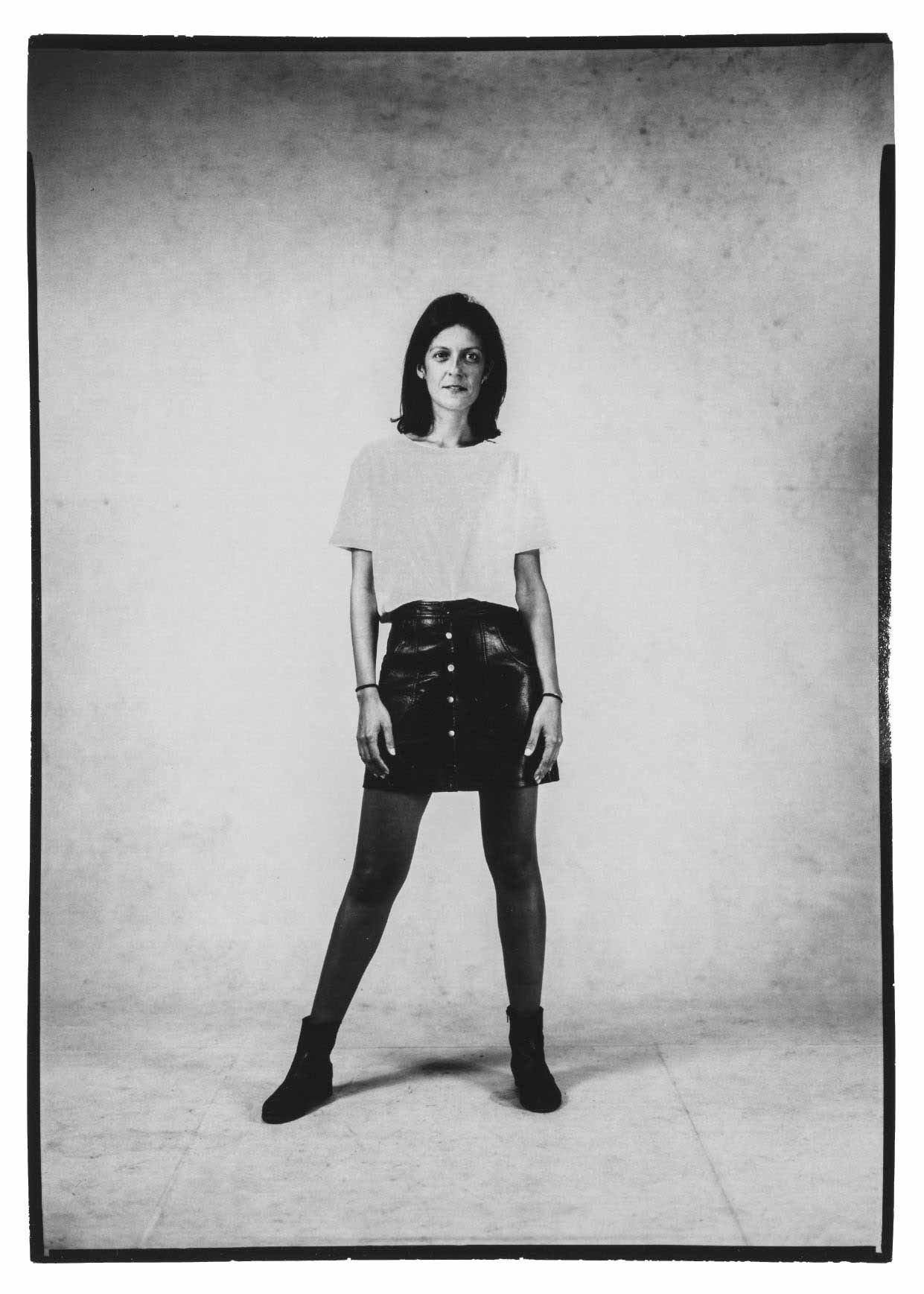

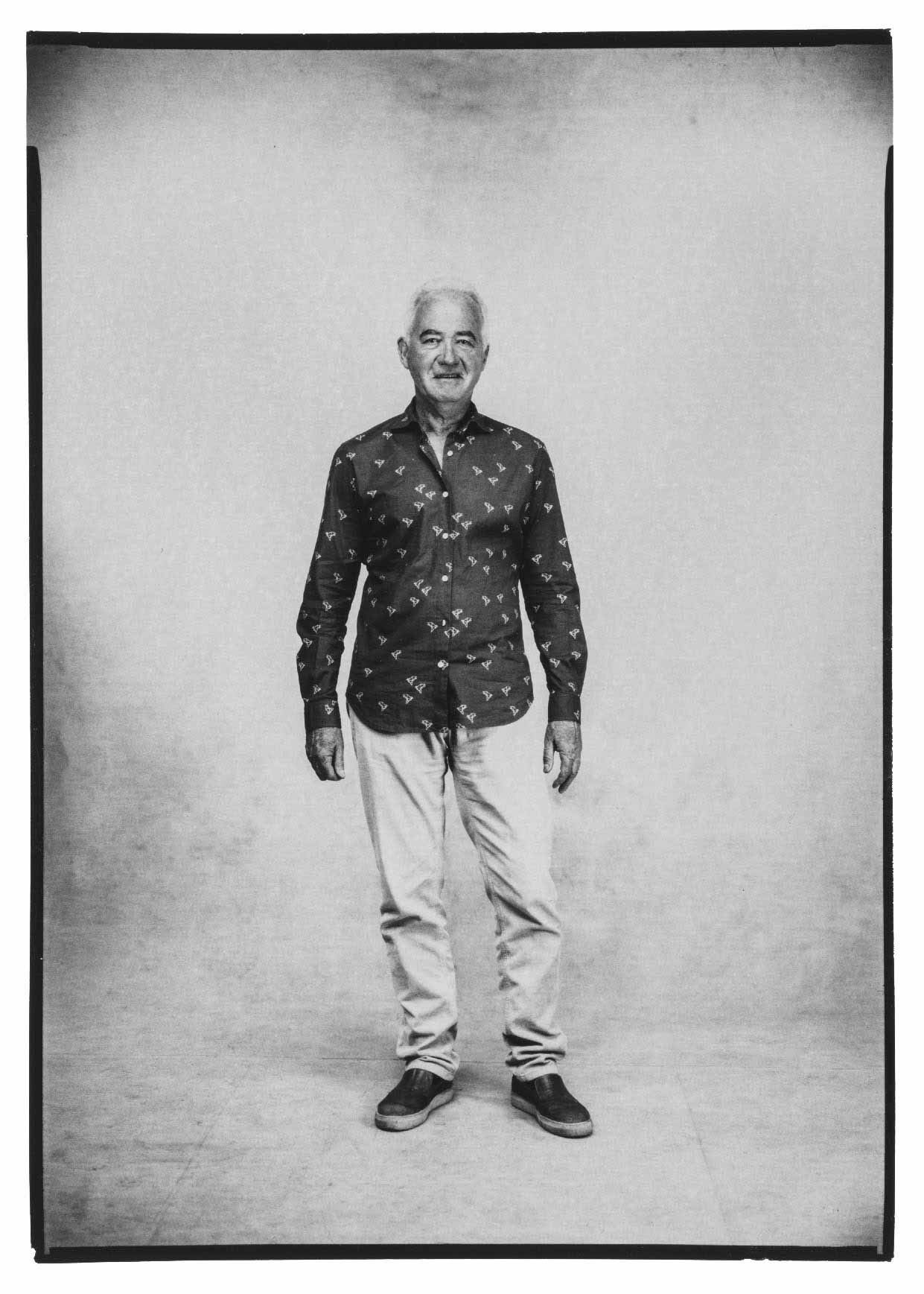

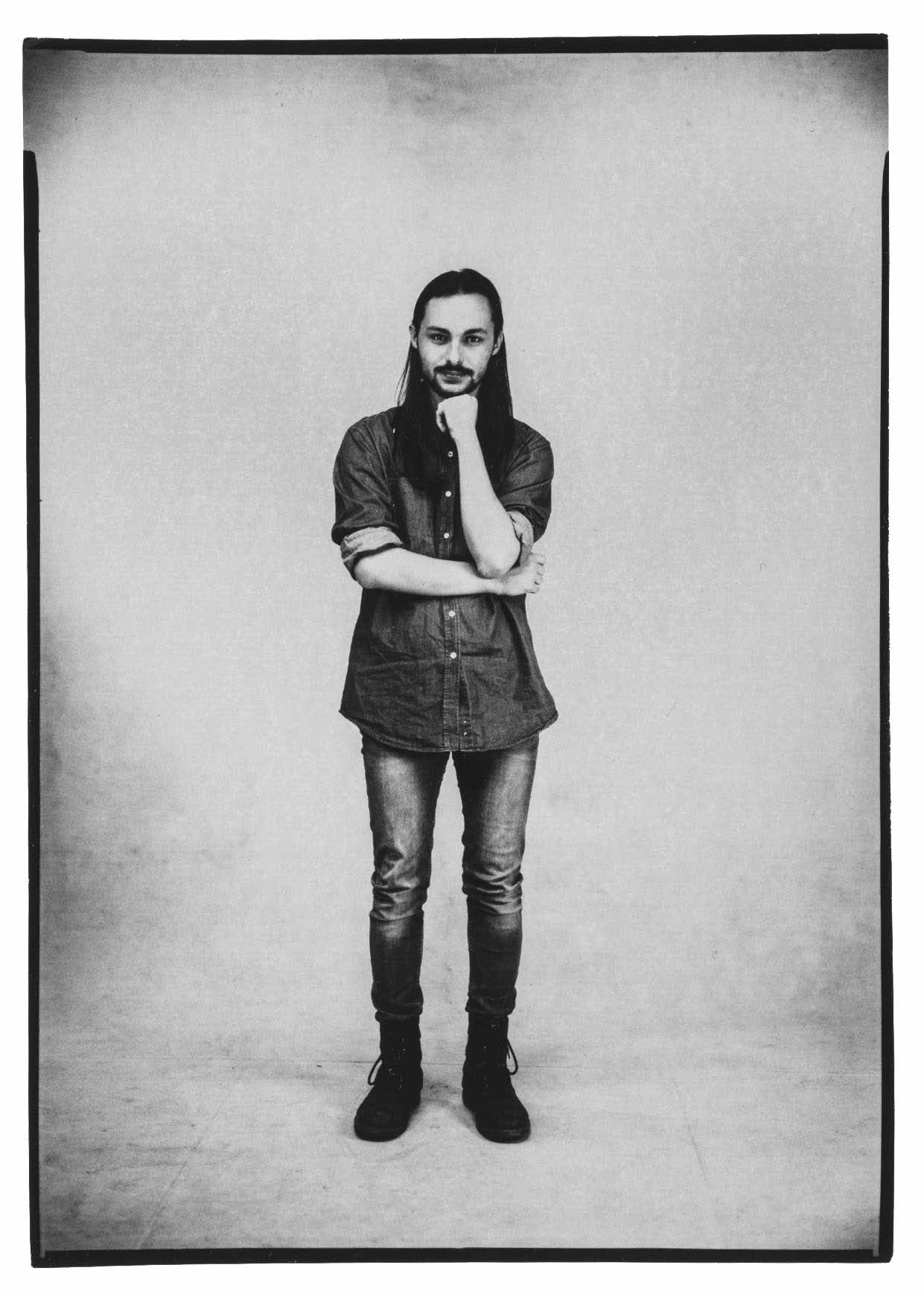

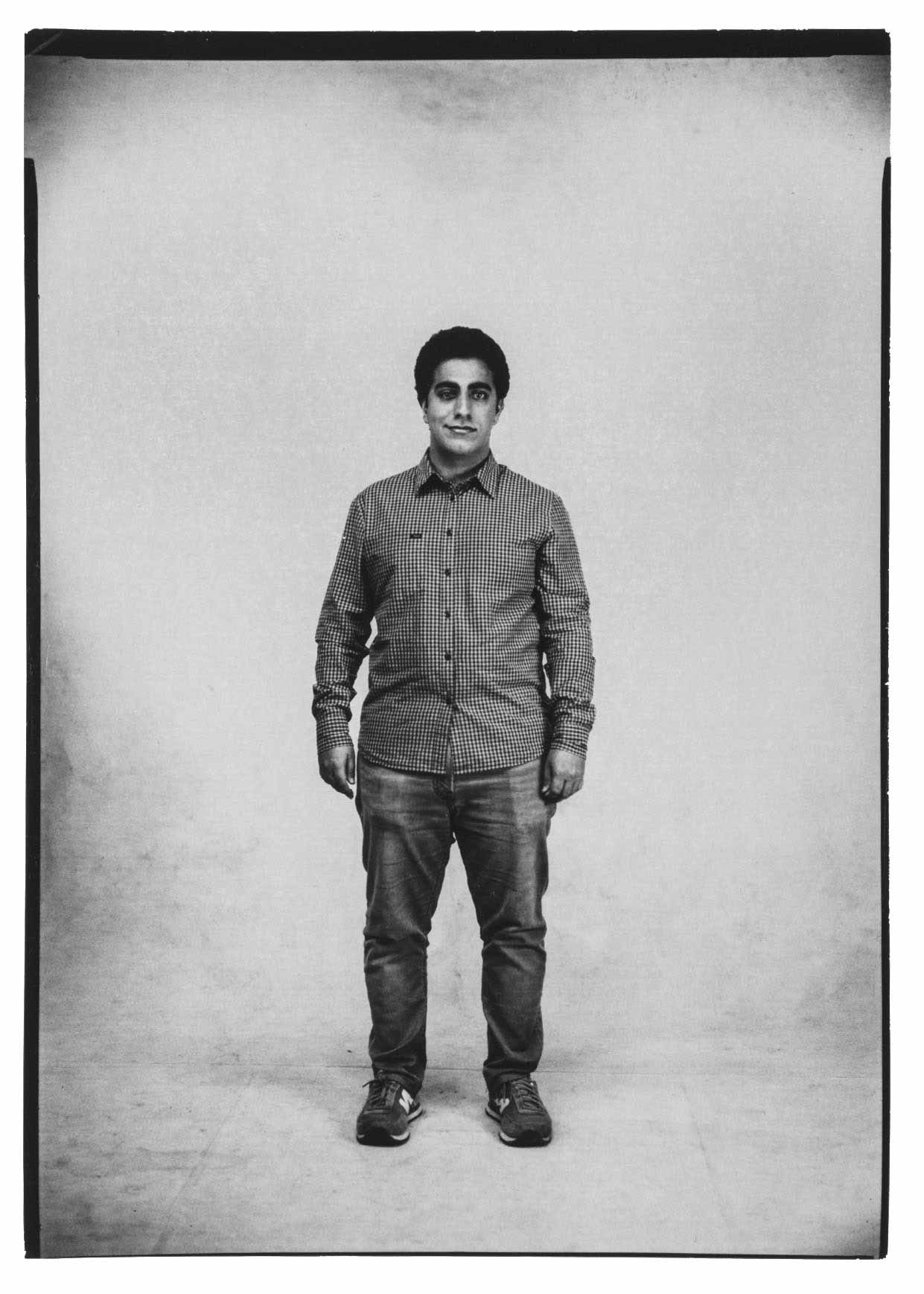

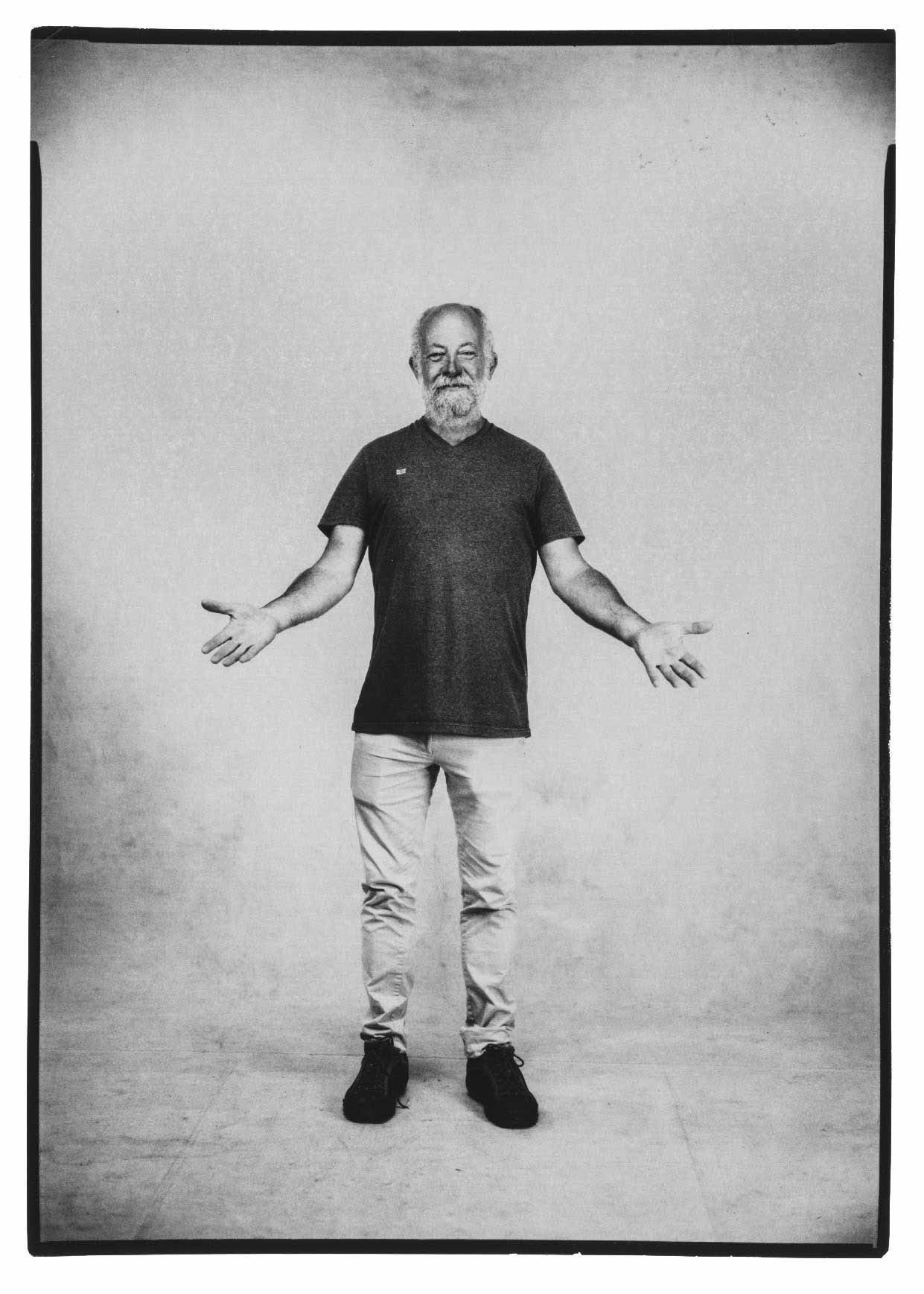

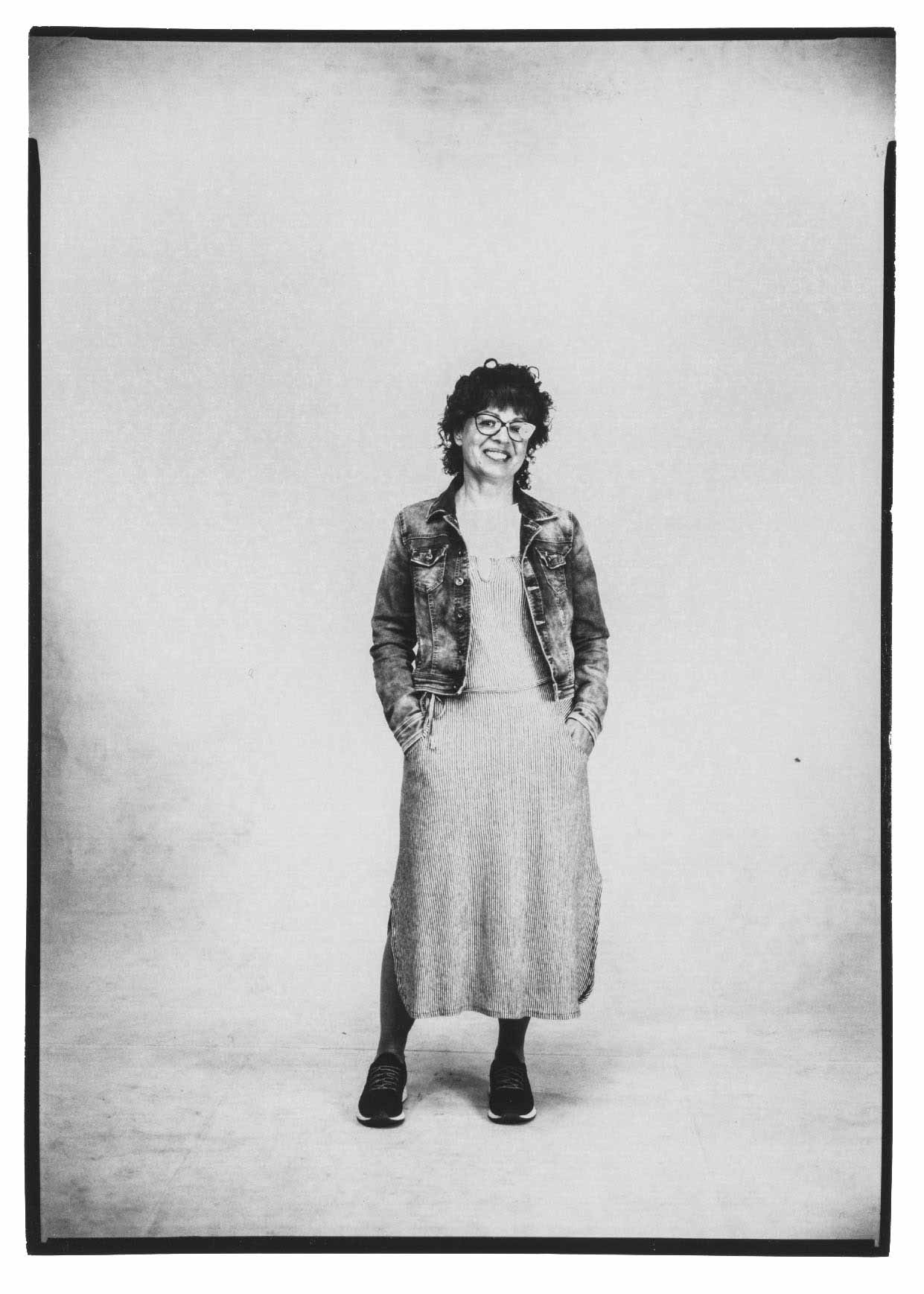

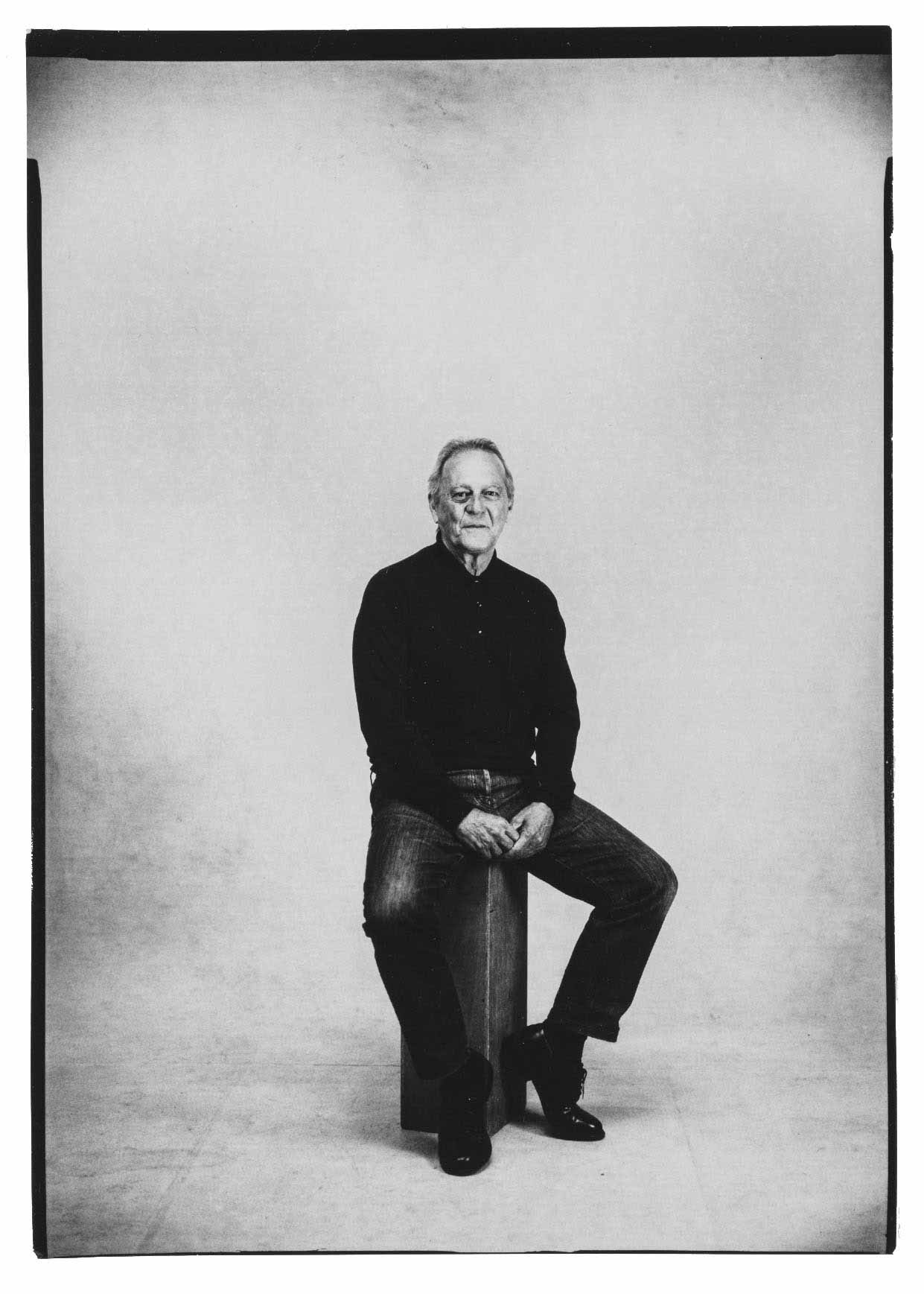

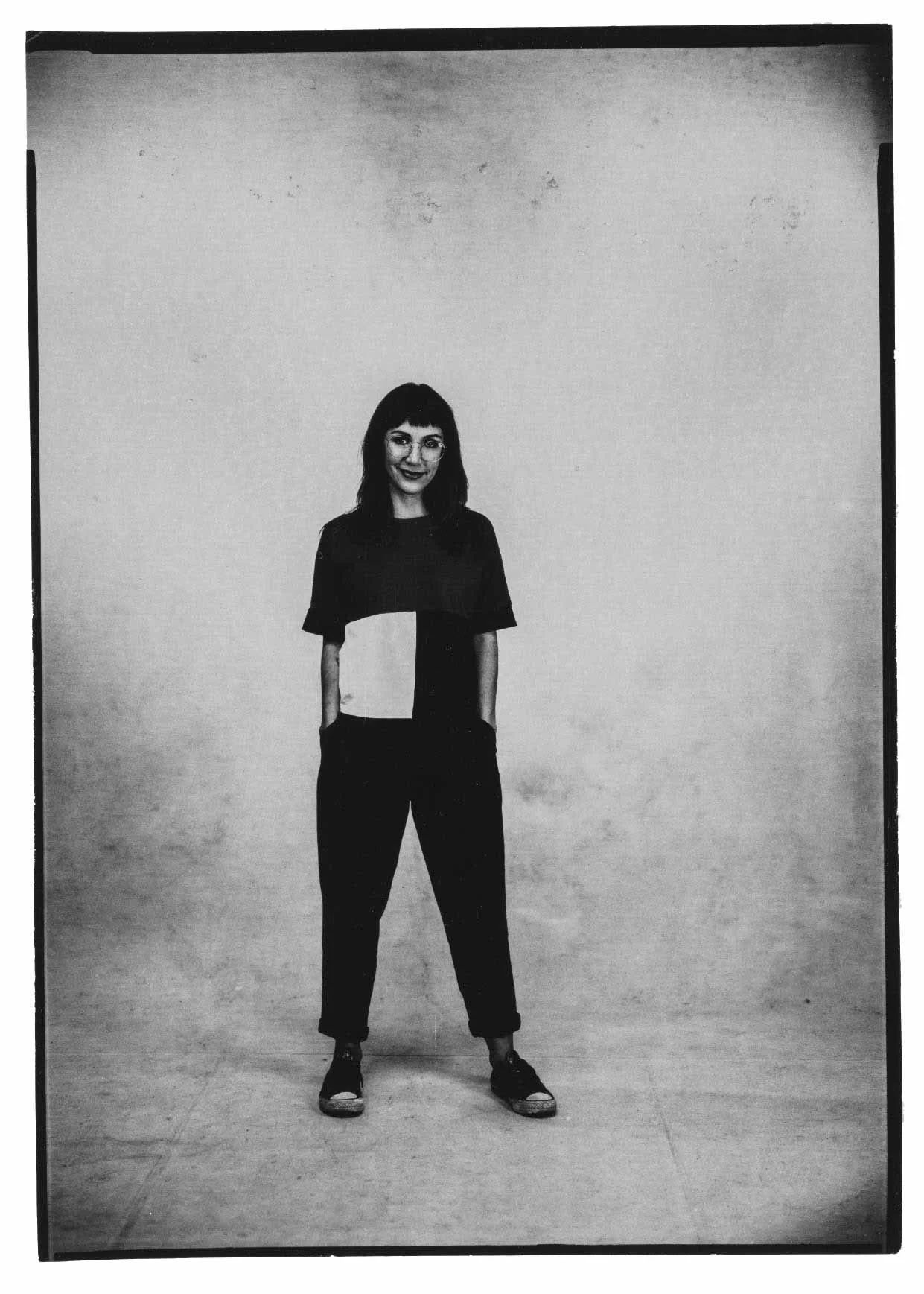

Present to Future es un obsequio similar. Una cápsula lanzada a las aguas del tiempo y el espacio, esperando a que alguien la encuentre. En 2017, los artistas Jordi Bernadó y Santiago Garcés realizaron 372 retratos, cada uno una única persona, en el transcurso de seis días. En su conjunto, las fotografías componen un extraño álbum familiar, un archivo casi espectral. Su estética evocadora es, en parte, fruto de una decisión técnica: las fotografías se realizaron con una cámara de placas en un único disparo sobre papel positivo. Es decir, no existen negativos, no se pueden reproducir. Cada retrato es único. Pero no es sólo eso, hay algo más. Antes de disparar, a los retratados se les recuerda la finitud de su vida: en 200 años ya no estaremos aquí, nada de lo que somos existirá. Excepto, tal vez, esta fotografía. Y, con esa reflexión, se les planteaba una pregunta: ¿qué querrías que vieran quienes encuentren tu retrato? ¿Qué querrías decirles?

Las 372 fotografías dejan un trazo permanente, congelan el instante preciso del disparo. Gracias a ellas, una parte de ese momento, de esas personas, sobrevivirá a los estragos del tiempo. Como aventuraba Roland Barthes, las ausencias hablan a través de sus retratos. No podemos saber quién verá nuestra fotografía, no podemos imaginar cómo será su vida, ni qué sentirá al vernos. Pero tenemos una certeza: sabrá que ya no estamos; sabrá que, en el momento de tomar la fotografía, fuimos conscientes de que moriríamos; sabrá, también, que nuestro retrato es un mensaje destinado a encontrarle, un regalo del pasado para el futuro. Como los gramófonos del Voyager, es imposible predecir el camino que tomarán los retratos, pero imaginar diálogos entre tiempos nos permite burlar al olvido.

Present to Future nos vincula –aunque de forma simbólica e, incluso, fantasmal– a lugares y personas a quienes no conocemos ni podemos anticipar, pero a quienes debemos nuestra permanencia. Como un alter ego diferido, alguien nos aguarda al otro lado, lejano y próximo a la vez, un reflejo de nuestra imaginación, un pliegue de nuestra consciencia. Y con él, una certeza. Alguien encontrará el mensaje. Los 372 retratos. Los discos interestelares. Alguien vivirá.

A project by Jordi Bernadó and Santiago Garcés.

Taking advantage of a favourable alignment between Jupiter and Saturn, the Voyager programme launched two spaceships on an interstellar mission in 1977. Each spacecraft carried a gramophone record with a compilation of terrestrial sounds: animal roars and songs, human voices, laughter, the sound of footsteps, messages in Morse code, etc. The aim: to send a message. Of love, of hope? Although the chances of finding extraterrestrial life are minimal, Voyager is an exercise of faith. Faith in the encounter, in the possibilities of understanding each other across distances.

Present to Future is a similar gift. A capsule launched into the waters of time and space, waiting for someone to find it. In 2017, artists Jordi Bernadó and Santiago Garcés took 372 individual portraits over the course of six days. The photographs make up a strange family album, an almost spectral archive. Their evocative aesthetic is partly the result of a technical decision: the photographs were taken with a plate camera in a single shot on direct positive paper. In other words, there are no negatives, they cannot be reproduced. Each portrait is unique. But that is not all, there is more. Before shooting, the sitters are reminded of the finiteness of their lives: in 200 years we will no longer be here, nothing of what we are will exist. Except, perhaps, this photograph. And, with that reflection, they were asked a question: what would you want those who find your portrait to see? What would you want to say to them?

The 372 photographs leave a permanent trace, they freeze the instant where model and camera meet. Thanks to them, a part of that moment, of those people, will survive the ravages of time. As Roland Barthes ventured, the absent speak through their portraits. We cannot know who will see our photograph, we cannot imagine what their life will be like, nor what they will feel when they see us. But we have one certainty: they will know that we are no longer there; they will know that, at the moment of taking the photograph, we were aware that we would die; they will also know that our portrait is a message destined to find them, a gift from the past to the future. Like the two Voyager gramophones, it is impossible to predict where these portraits will go, what they will find, yet imagining dialogues across time and across space allows us to momentarily elude oblivion.

Present to Future links us - albeit in a symbolic and even ghostly way - to places and people we do not know and cannot anticipate, but to whom we owe our permanence. Like a deferred alter ego, someone awaits us on the other side, distant and near at the same time, a reflection of our imagination, of our consciousness. And with it, a certainty. Someone will find the message. The 372 portraits. The interstellar discs. Someone will live.